An interview by Fabien Pinaroli

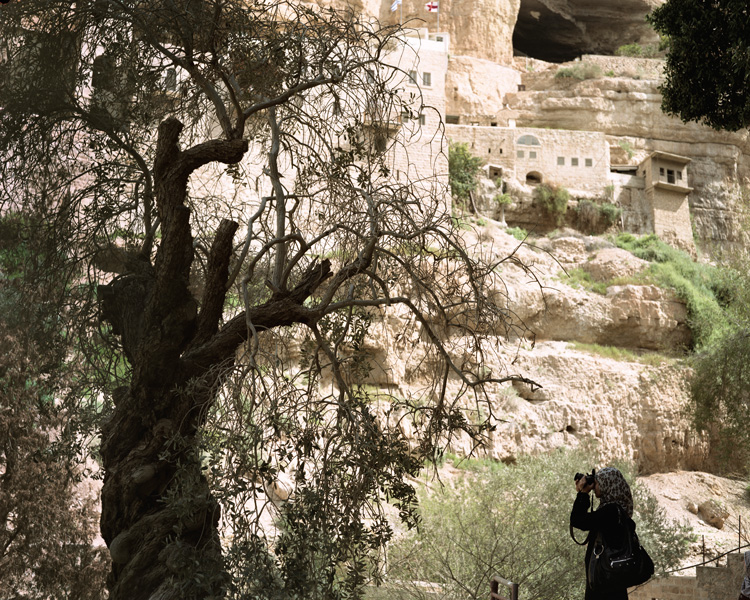

For more than twenty years, in her encounters and the resulting portraits, Valérie Jouve has been navigating among reference points composed of historical markers such as architecture in peripheral zones, or the habituses of contemporary human beings. These markers are also strongly imbued with questions that are posed by anthropology – among others, that related to respect for the people – that provide its main resources. Since 2008, Jouve has been travelling frequently to the Middle East, in particular Israel and Jordan, and cultivating a dialogue with its people and territories. The exhibition Cinq femmes du pays de la lune (Five women from the country of the moon), at the Musée d’art contemporain du Val-de-Marne (MAC/VAL), paints a portrait of a city, Jericho, and its surrounding area. Jouve invited four Palestinian women, Rana M. S. Abukharabish, Suha Y. M. Abusharar, Yasmin M. M. Abu Awad, and Jamila I. M. Thalja, to work with her to make images, outside of the conflict, to build a different portrayal of Palestine. As they guided her, they learned to think differently about images.

Fabien Pinaroli: The handwritten sentence written on the first wall of the exhibition, like an opening comment in a photo album, offers “a collective reflection on the image in a place where religion prohibits images.” You broaden the statement a bit further on: “A photography project in a territory that has become, over time, the expression of a vision of the world.” Can you talk about the path of this project in terms of these two aspects?

Valérie Jouve: Based on a prohibition – the supposed prohibition on images in Islam – the plan was to take a picture of um Hassan (Jamila Thalja) for my series Les personnages. She didn’t want me to do this, and I tried to shift the question: if I couldn’t take a picture of her, on the other hand, she could take pictures, and each picture would be a sort of self-portrait. And so we began to discuss a shared project, and um Hassan had the idea of inviting three other women to join us. As she said during a visit to the exhibition, “I am above all Syrian, even though I’ve lived here for twenty years, and for a project in Palestine I thought it was important that there also be Palestinian women, and it would also provide more energy.” When we agreed to work together, the question arose about the subject of this group work. At the beginning, I wanted to encourage each of them to produce a kind of self-portrait through images of her home, her family, her everyday life. but very quickly, I sensed a reticence – or, rather, a lack of interest – and so we talked about it, and at this point they shared with me their desire to travel. And that was wonderful, as they were reaching out to me on a subject that I know well: territory, and how their territory is a sort of portrait of themselves – in other words, how these figures are inscribed in the territory of Jericho or how they inscribe their living environment there, and especially, eventually, how the Palestinian identity can be discovered there.

Some ethnologists totally assume their “situated” position, or even leave the scientific field to write novels or make filmed essays; they then speak in the first-person singular, as an artist would do. In Jericho, you did sort of the opposite, didn’t you?

No, I don’t think I did the opposite, as I have never questioned my identity as an artist. From the beginning, I know that I had to make images to accompany my era, the community of human beings in my era, but I was always uncomfortable with my status as an artist, even though the art world, by being interested in my work, gave it this status, and that is the strength of art. I conduct my work as research, and I think it’s important that unique approaches can exist. After, it’s a question of categories: one finds oneself sort of “sitting on the fence,” but I have always liked instability, both in thought and in the social sphere. My work began when I was studying anthropology, my necessity comes from that, and so this exhibition is perhaps the most explicit with regard to my intellectual sources.

There is talk of “embedded journalists” during conflicts and military operations. The expression is pejorative (denoting a lack of objectivity), but isn’t Cinq femmes du pays de la lune an embedded project, in two ways? First, you are “embedded” with these four women, who guide you through their city, through its physical and human geography and its history; second, they are “embedded” with you in your photographic project. What do you think of this definition?

It pleases me for its multiple meanings in this context. In fact, simply, we chose to “embed” together to construct this work as a little utopia of our “liberated Palestine”! It is true that the project was very rich, given the back-and-forth among our respective experiences. For example, um Hassan, being a foreigner, allowed me not to be the only one from outside. She is Syrian. Suha was born in Hebron and has lived in the Ain Sultan camp for a number of years. Rana and Yasmine are from Jericho (from this same neighbourhood), and I am French but have been living in Jericho for a few months every year for four years. Each had her own reason to feel like she belonged to this territory and, especially, to recognize the others’ sense of belonging. For everyone can feel at home there; it is a founding land for many civilizations. Since Roman times, this part of the Middle East has always been passed through, and that’s actually the paradox with Israel: for the first time, an invasion resulted in expelling Palestinians! There are communities that arrived hundreds of years ago (from Senegal and Morocco, for example). The problem for the Palestinians doesn’t have to do with welcoming others – their collective history has been moulded by it – but this is not about that!

How you present your work has changed in recent years, and you have moved the focus from the West to the Middle East. At MAC/VAL, you presented Le pays de la lune like a family album in images, sounds, and words. How did you decide upon this break with the classic format of the exhibition?

The expression “family album” is quite lovely, as this is how we built a sort of family. My work there comes from far, in fact. Even though I have always felt close to Arab culture (I was married to a Moroccan man for twenty years), thirty years ago I was scared to make a work in these countries, scared of bringing unconscious traces of our colonial past. but after 9–11 certain images rose up, like a sort of reminiscence of children’s tales, in which Arabs are on horses brandishing sabres, killing and raping women and children. (The visit to Israel and Palestine in 2008 also shocked me a good deal!) I was very despondent, and I wanted to continue my work there, and I also wanted to be able one day to work on exhibition layouts in which images from here and there on the same themes could coexist to create dialogue. All of these experiments have not been radical changes in recent years, but a progressive shift that clarifies the work. For example, the images that I call Les Personnages, from the mid-1990s, are meaningful here.

Today, after photography and cinema, I want to open my mind to sound, which, on its own, helps to produce images. This group work is part of a good energy; I like the absence of signature. And I wanted to give it a purpose as a group work; above all, I didn’t want to work with these four women and then appropriate their images. What interests me is the phenomenological aspect between us and the sites, as happens often in my work. The subject of study – the territory – is not the only purpose. The shape of the narrative by these five women, without anything impeding the discovery of the territory, leads the viewer to reflect on how we fit into the territory and brings meaning with regard to the human sciences.

Two of the exhibition walls are painted grey, different from the others, which are white. This space, more closed off than the others, is devoted to a neighbour of Um Hassan’s, an elderly Palestinian man, who talks about 1948, the geopolitical situation that prevailed during the Israeli invasion, and the humiliation felt by those who lost their land and were exiled. His words are full of bitterness. His memory is fragmented and has altered the events that he relates. Sometimes, your comments are added on paper, completely plainly. The Israel–Palestine conflict is omnipresent, so can we consider that it is the real setting for these photographs, rather than the aridity of the “country of the moon”?

In my exhibitions, I generally privilege the relationship between the images, but here, I can say that each wall is a work, or each place. Each asks a question, and that interests me. We named the walls for places (going from “Ain Sultan,” the Jericho neighbourhood where um Hassan lives, to the “Dead Sea”). The two walls that you’re talking about are called “camps.” Yes, in a sense, the conflict is already there: when one says “Palestine,” one hears “conflict.” You do it yourself, seeing the conflict everywhere even though none of the images shows it (no wall, no checkpoint). There’s just this man talking about 1948; as you noted, his memory is faulty, but you’ll note that his bitterness is directed more toward the English and French than toward the Israelis. This exhibition shows the beauty of this landscape as many visitors have seen it. We don’t know this country except in its relationship with its neighbour, thus in the framework of conflict. Throughout the space, the walls go from white to brown with, it’s true, these two more radically dark walls as an isolated point to signify the origin of the country’s situation; it is the only point that speaks of conflict, and it does so in a discursive way. but it overflows into the images anyway, in a less marked way but symbolically just as violent: Israeli flags on private beaches, the only ones accessible to the Dead Sea in Palestinian territory.

In the exhibition, it is impossible to distinguish which image is attributed to whom. Most of them are series of photographs ranging from 18×27 cm to 40×50 cm format, all presented on picture rails, recto-verso. One series stands out, exhibited on the wall, as the photographs are bigger. These images are yours; they frame the exhibition. Don’t they reflect your position in the project?

When I proposed to the women to make a work with me on their territory, it was obvious that this would lead to a collective. It was an exchange, and it interested me as such. Very quickly, I realized that we had to move ahead with the photographs of the territory and at the same time develop the narration, our own history. I do recognize myself in this exhibition (its general rhythm, its musicality, its evolving chromas). Perhaps my authority appeared only by necessity to contribute my experience, but it did not go further. The women contributed their knowledge of the territory, and one can recognize them in the images that they made. It is quite beautiful; in fact, it’s almost a philosophical reflection – the self in the other (as in the series Les personnages). Yes, this exploration is a new milestone. I have always tried to understand how the human community works, and especially how it is evolving today: bodies and places, me and the models (who are more actors, in fact, since I talk with them about the initial idea and we work together on it afterward). but I don’t want to make a serious academic work; I want to bring in all the poetry generated by the absurd reality of our human worlds. And especially, of course – in fact, simply, we chose to “embed” together to construct this work as a little utopia of our “liberated Palestine”! perhaps most important –this work shows the point to which resistances are there and function, how they give this poetry even more strength! It is not for nothing that these four women are all unique in their respective societies. They are also personalities, and that’s why I wanted to work with them.

The presence of these women’s bodies is atypical. They are not photographed first; they are photographed later, but as veiled silhouettes in the process of taking pictures – thus, gazing at their own world. Finally, these bodies are photographed as portraits, unique bodies, faces uncovered, including the portraits of you. How did you arrive at this point?

We’ve already spoken about the origin of the project around the prohibition on images, so at the beginning, I paid attention to that. Most representations of these women take account of this reality. I didn’t want to force anything; on the other hand, the one who didn’t want her photograph taken saw how much pleasure the others took in it. Suddenly, she said yes. There was a festive side to this project, as it was a sensation for them to travel within their own country (one of the women spoke of rediscovery during visits to the exhibition that they made with me). When we had work days together, we were all very enthusiastic: the car trips were loud, we sang at the top of our voices, the women sometimes called out to passers-by – something that was normally improbable, especially to men. It was like they were returning to childhood! So, it seemed important to keep this energy; I think that that’s what gives the sense of a family album.

Translated by Käthe Roth