Queening the Pawn

by Caroline Nepton-Hotte

“Competition among multinationals these days is likely to be a three-dimensional game of chess: The moves that an organization makes in one market are designed to achieve goals in another market in ways that aren’t apparent to its rivals.” – Ian C. MacMillan, Alexander B. van Putten, and Rita Gunther McGrath, 20031

“It’s a great huge game of chess that’s being played – all over the world – if this is the world at all, you know. Oh, what fun it is! How I wish I was one of them! I wouldn’t mind being a Pawn, if only I might join – though of course I should like to be a Queen, best.” – Lewis Carroll, 18712

“We tend to think pawns are expendable. We think wrong.” – Peter Zhang, 20133

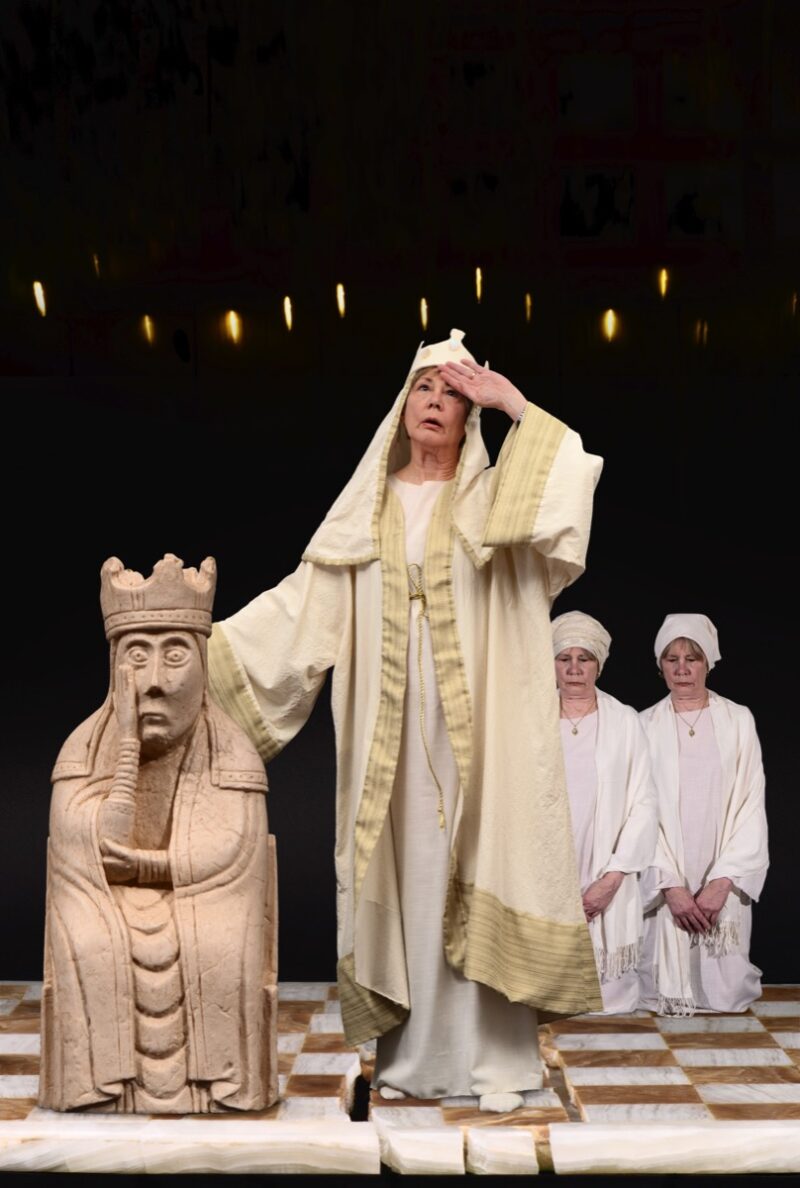

The marble chessboard drifts like an ice floe on the sea at night. Walrus-ivory rooks, bishops, and a king are buttressed by an almost equal number of human pawns, uniform in cream-coloured commoner’s dresses, headscarves, and necklaces, and varied in expressions of grief and despair. One pawn is without an ivory figure to defend: her beleaguered queen, who stands alone in the foreground, staring out into the dark abyss at the front edge of the board. A bright-red door with a rusted bolt and padlock delimits the scene’s recess. The image is a paradoxical one, positing seemingly infinite outcomes and a limitless beyond against a backdrop of confinement and constraint.

Rules of Engagement is a work from Suzy Lake’s series Game Theory: Global Gamesmanship (2018–19). The series was inspired by Lake’s visit to the British Museum, where she encountered the twelfth-century Lewis Chess Piece Collection, considered to be one of the oldest complete medieval chess sets. Struck by the carving of the queen, whose hand was positioned heavily against her cheek, Lake read into the queen’s face and pose several possible emotions, ranging from despair, to grief, to surprise, and found resonance with the oppressive political and social climate of the late 2010s. Shrinking herself down to the size of the carved ivory figures, Lake assumes the form of a human chess piece, alternating between the roles of the queen and the pawns. Full-body portraits of Lake in these roles imbue the pawns with emotional detail not afforded the original carvings, and the queen is endowed with a complex spectrum of emotions corresponding to the weight of her power and responsibility. In Lake’s series, other power players, such as the king, and those with more range of movement across the board – such as the knight and rook – are obscured by Lake’s repeating figure alternating between the queen and the pawns, making explicit the important relationship between them.

Prior to the fifteenth century, the queen’s movements, like those of the pawns, were limited to one space per turn; the pawn, meanwhile, upon advancing to the eighth rank, is promoted to queen, rook, bishop, or knight, the role of queen being the most advantageous promotion. In Lewis Carroll’s 1871 children’s book Through the Looking Glass, and What Alice Found There, the titular Alice, having stepped through a mirror, finds herself in a world in which everything is reversed and life is a quest organized around a game of chess. Challenged by the Red Queen to advance from the second rank, where she begins her journey as one of the White Queen’s pawns, to the eighth rank, Alice succeeds and becomes a queen. Like Alice, Lake’s embodied game play evokes the centuries-old custom of human chess games, a form of play that metaphorizes the games played on global social, political, and economic stages.

In a previous work, Authority is an Attribute Part II (1991), which Lake made in collaboration with the Teme-Augama Anishnabai of Bear Island in support of their land-claim dispute with the Ontario government, a section titled The Game Players featured seventeen photographs documenting a chess game between two men dressed in suits amid a forested backdrop. Although, prior to Game Theory, this is the only explicit reference that Lake makes to chess, a key skill in chess is pattern recognition, which applies to how she identifies and returns to predominant themes throughout her oeuvre – in particular, issues of power, authority, and control; as Martha Hanna has written, “The attention to power relations that feminism implies may be seen in Lake’s work as symbolic of a personal struggle, and her artwork is evidence of her progress.”4 In Choreographed Puppets (1976–77), Lake’s wrists and ankles are bound by straps that are hoisted over a wooden structure, with Lake appearing in the stage area that doubles as a frame. Two “puppeteers” manipulate the straps from overhead, causing her to dangle like a marionette, ceding control of her movement. In ImPositions #1 (1977), her arms and legs are bound by a strap wound around her body, and she is further constrained by the claustrophobic rows of wooden lockers that flank her; in Vertical Pull #1 (1977), she again appears bound and pulled by an out-of-frame actor, her descent down a flight of stairs blurrily documented in a grid of twelve images. In each of these works, Lake is the constant (as she has stated, “I don’t try to say what my identity is. I’m not some heroine recounting my life. I needed a constant, a vulnerable subject for a reference point. The reason I use myself as a model is because I’m always on hand, always around”5), but her movement and agency involve interdependence – a key element of game theory – at the hands of the other.

The grid is a recurring organizational strategy in Lake’s work; in Game Theory, it appears in the form of the chessboard on which the human and non-human figures stand, literalizing a McLuhanesque figure-ground relationship through which Lake’s earlier works can also be read: it is not simply the moves an actor makes on a board or a stage or in front of a camera, but the structures and systems – the total environment – that direct movement, and to which as much, if not more, attention must be paid. The chessboard is not an insignificant support for the game unfolding on top of it but a critical determinant of its outcome. The queen, however, holds the power to subvert the figure-ground interplay; in a “probing” dialogue between media theorists Eric McLuhan (Marshall’s son) and Peter Zhang, on the subject of chess, McLuhan observes, “The Queen always holds the power. She is the power behind the throne. When she is relegated to the sidelines, ignored, she assumes absolute power – as the ground. It is a very subtle arrangement in that game, with its own kind of truth.”6 When Lake poses as the queen, she embodies this power, cycling through expressions and gestures of defiance, authority, and the weight of responsibility.

Unlike Alice’s looking glass, the ominous red door in Rules of Engagement appears impenetrable. But it also evokes another earlier work of Lake’s: Pre-resolution: Using the Ordinances at Hand (1983–85), which Lake created in the era when Orwell’s 1949 cautionary tale Nineteen Eighty-Four is set, and when Apple released its genre-smashing television ad “1984,” in which freedom from uniformity – represented by a track star heroine hurling a sledgehammer at a Big Brother–like figure on a large screen – is promoted to sell products. Lake’s series features her wielding a sledgehammer and smashing through a red-painted wall to its wood-slat structure. Confined by the image’s surface, she hatches an alternate escape plan: the image’s recess. Reading Lake’s Game Theory at a forty-year remove from Pre-resolution, the message, sadly, is not quite so liberatory; her transposition of her body onto the medieval chessboard magnifies enduring cycles of human violence and conquest and the other side of the looking glass as a dystopian reality from which we cannot return. The cracks in her marble chessboard appear less a path to escape than an irreparable systemic rupture, illustrative of a system hurtling us toward a singular, devastating endgame.

[ Complete issue, in print and digital version, available here: Ciel variable 127 – SISTERS, FIGHTERS, QUEENS ] [ Complete article in digital version available here: Queening the Pawn]

Notes

1 Ian C. MacMillan, Alexander B. van Putten, and Rita Gunther McGrath, “Global Gamesmanship,” Harvard Business Review 81, no. 5 (May 2003): 62.2 Lewis Carroll, Through the Looking Glass, and What Alice Found There, 1871.

3 Peter Zhang, in Eric McLuhan and Peter Zhang, “Media Ecology: Illumi-nations,” Canadian Journal of Communication 38, no. 4 (2013): 467.

4 Martha Hanna,

Suzy Lake: Point of Reference (Ottawa: Canadian Museum of Contemporary Photography, 1993), 5.

5 Suzy Lake quoted in Sophie Hackett, “A New Scene in Montreal,” in

Introducing Suzy Lake, ed. Georgiana Uhlyarik (London: Black Dog Publishing, 2014), 68.

6 Eric McLuhan, in McLuhan and Zhang, “Media Ecology,” 468.

The Artist

Née en 1947 à Detroit, Suzy Lake immigre à Montréal en 1968 alors qu’elle entame sa pratique artistique, puis s’installe à Toronto en 1978, où elle vit toujours. Cofondatrice de Véhicule Art Inc. (Montréal, 1972) et du Toronto Photographers Workshop (Toronto, 1978), elle fait partie des premières femmes artistes au Canada à travailler en performance, vidéo et photographie pour explorer les politiques du genre, du corps et de l’identité. Elle participe à d’importantes expositions, notamment, dans les années récentes, WACK! Art and the Feminist Revolution et Traffic: Conceptual Art in Canada 1965–80. En 2014, le Musée des beaux-arts de l’Ontario présente Introducing Suzy Lake, une rétrospective sur l’ensemble de sa carrière, accompagnée d’un catalogue conséquent.

www.suzylake.ca suzylake.ca

The Author

Erin Silver is an associate professor of art history and critical and curatorial studies at the University of British Columbia. She is the author of Taking Place: Building Histories of Queer and Feminist Art in North America (Manchester University Press, 2023) and Suzy Lake: Life & Work (Art Canada Institute, 2021), and the co-editor (with Amelia Jones) of Otherwise: Imagining Queer Feminist Art Histories (Manchester University Press, 2016) and (with taisha paggett) of the winter 2017 issue of C Magazine, “Force,” on intersectional feminisms and movement culture.