[March 27, 2024]

By Michel Campeau

Consciousness is thus memory – conservation and accumulation of the past in the present. But all consciousness is anticipation of the future. Consider the direction of your mind at any given moment: you will find that it is occupied with what is, but mainly with a view to what will be. Attention is an expectation, and there is no consciousness without a certain attention to life. The future is there; it calls up to us – or, rather, it pulls us to it: this uninterrupted traction, which makes advance on the road of time, is also the reason we are constantly acting. All action is an encroachment on the future.

Henri Bergson, “La conscience et la vie,” in L’Énergie spirituelle, 1919, 10–11 (our translation).

I was in late adolescence just a few years before the advent of the Groupe d’action photographique, the Groupe de photographes populaires, Groupe Photocell, the Collectif de l’imagerie populaire de Disraeli, and Camille Maheux and her friends in Plessisgraff – before our paths crossed and I also met Gabor Szilasi, Pierre Gaudard, Sam Tata, John Max, and others. In the interval between our childhood and adulthood, Szilasi had fled the Nazism and Stalinism of dictatorial Hungary to discover free jazz and North American counterculture; Gaudard was documenting the hard life and solidarity of the Quebec working class, not without having begged for permission from American executives; Max was making his Open Passport photographs; Tata was preparing to exhibit his images in pre–Cultural Revolution Shanghai; and Michel Saint-Jean was sowing the seeds of his Amérique québécoise.

Most, if not all, of them came from the working classes and met in childhood – neighbours and playmates or at elementary or high school – or when they received their professional training in the technical institutes that existed before the CÉGEP system was created, such as Loyola College, the Institut des arts graphiques de Montréal, and the Institut de technologie de Montréal. Some earned diplomas as engineers, graphic designers, and typographers; others studied literature or education. From this cohort emerged a plethora of talented artists, glowing with promise – photographers, filmmakers, journalists, and computer programmers. Soon or later, the fictions of false truth and artistic expression would win out over ideology.

Their lives unfurled in parallel to mine – I was living at the edges and in the ruts of a neighbouring parish. We visited almost the same places. Without knowing each other, our paths crossed as we made our way through school. This contiguous reality predicted a future that drew closer and closer to me without my knowing. I can still see the cavernous ambience of the basement where our friendship was sealed. It was on Rue de Normanville, in the Petite-Patrie neighbourhood, about a kilometre from Rue Drolet, where I lived bathed in the love, both autarkic and redeeming, of a matriarchal family.

They had the exposed souls of rebels; I had the obsessed soul of a romantic. It was impossible, then, to predict the future, except that it promised to be morose and monotonous, and that photography seemed to us so much truer than reality. All of us had quit our first professional jobs, and many of us had chosen photography as a way of standing firm in social reality. We would have not bosses – no, no, and no! – but, yes, we would have models. I owe them my freedom, my intellectual life, my curiosity, my insight, the artistic path of my life, and my obsessions about the truth of my origins and the meaning of existence, as I assumed, day by day, the quotidian protocols of my condition as an artist.

They were the ones – at least those who chose photography and would define its future and its early ideologies – whom I met later and who moulded my existence, who led me to disown my Christian friendships and define myself as someone other than nailed to a cross. With my parents and family, each in their own way, they taught me generosity, humour, respect for others, indulgence, and kindness – so necessary in our times. To live, and also to die. I would hope that the next day would be the first day of the rest of my life and that this essay will not be the last.

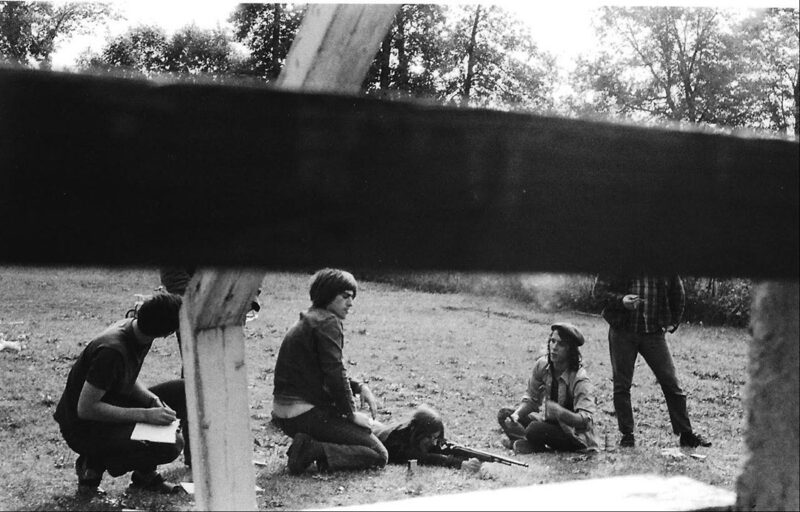

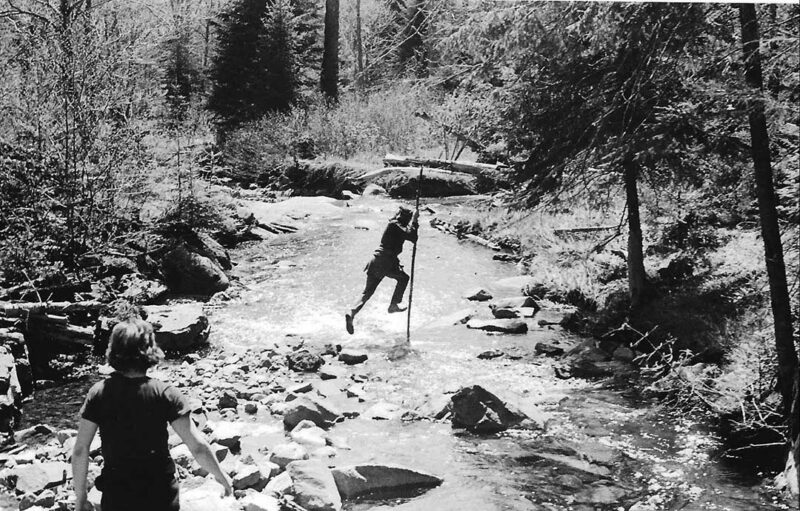

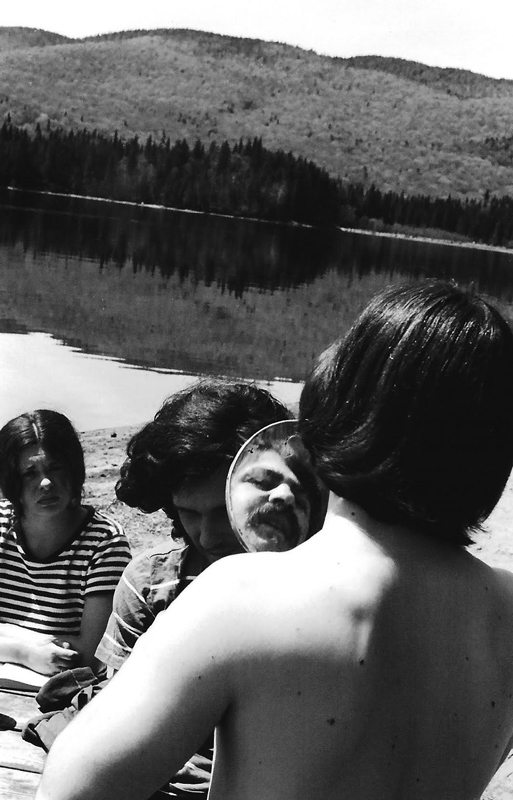

This story of late adolescence, of bonds and friendship, could be titled Being Twenty in Quebec in 1969. This spillway of memories took place in summer 1969, in a few simultaneous timelines – those on île Bizard on the shore of Rivière des Prairies, at Lake Monroe in Mont-Tremblant Provincial Park, and in private individual moments. The protagonists were dubbed, bizarrely, Le Groupe des 10 choses (The Group of 10 Things). No one was able to explain to me the meaning, the whys and wherefores, of this nonsensical name; it was lost in the mists of time. Although the hypothesis as I’ve remembered it is probably worthless, I’ll still attempt an explanation, as skimpy, scatterbrained, or probably obsolete as it might be: one of them reluctantly told me, as if it were a confession torn from him under torture, that the ten of them who formed this band of urban guerrillas called each other “Eh, chose,” “Hey, thing,” so they couldn’t possibly call the group anything else.

Because my texts aren’t paced with metronomic regularity, I told myself, before adding typographic signs, that it might be better to reconsider my priorities and their order so I wouldn’t lose sight of my commitments, the needs of my emotional life, and consequently wouldn’t launch myself blindly into an examination of this unexpected corpus.

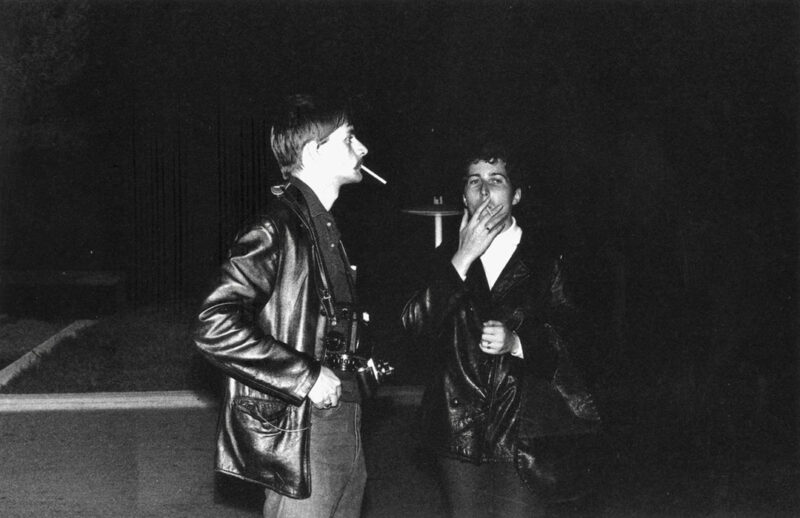

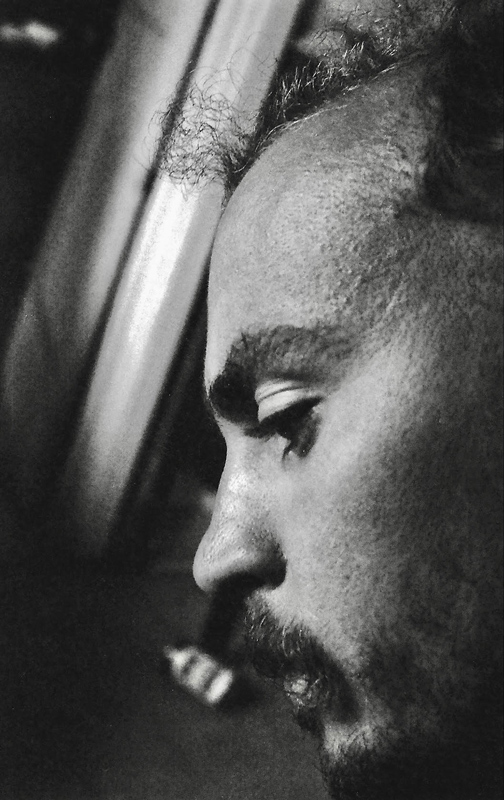

A lost cause. I feel ready to jump into the circle of fire. I look over and over at this visual prophecy that called out to me from the depths of my twenty-year-old self. I don’t know if these photographs were printed at the time, full framings or reframed. I suspect that they’re digitizations of the original negatives, that they were made with a small-format camera – I’m leaning toward a Minolta 35 mm, very popular among amateurs at the time – a camera with a normal, wide-angle, or telephoto lens.

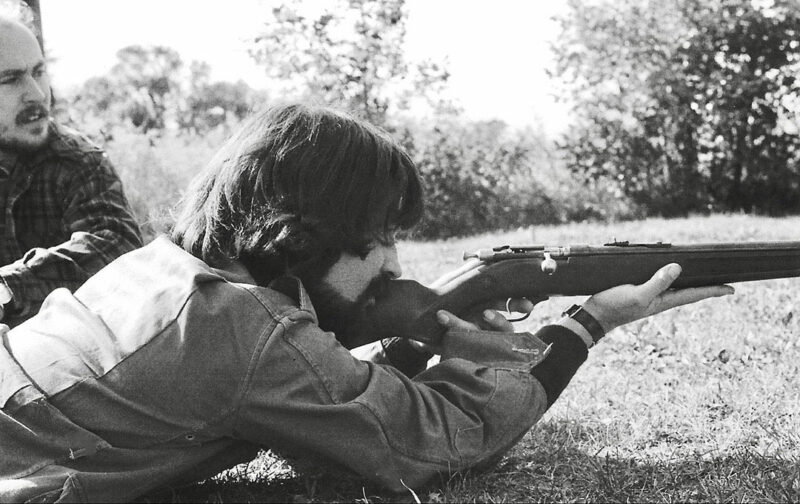

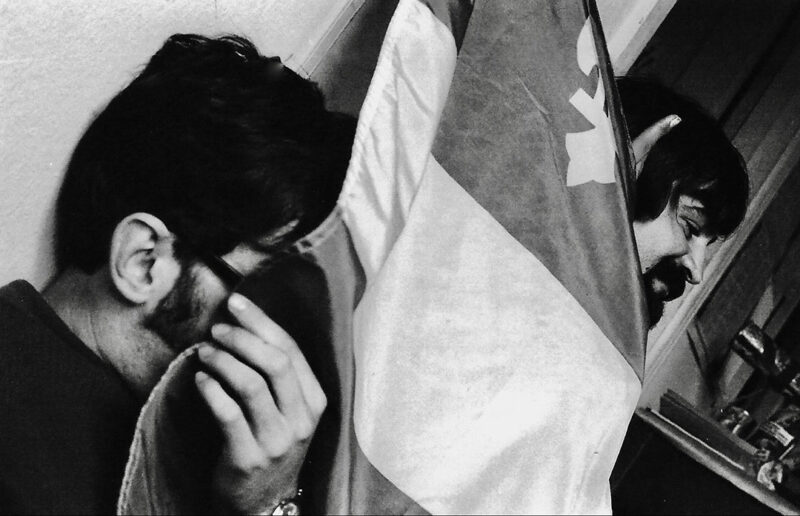

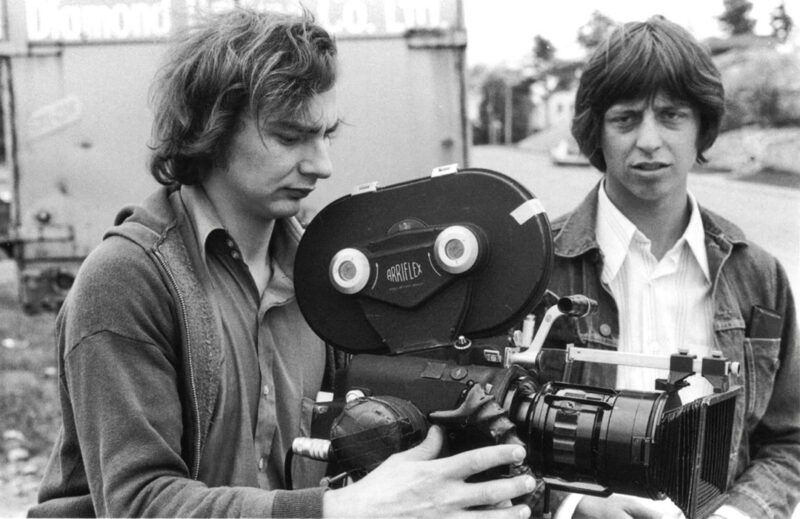

I haven’t forgotten that I’m writing about photographs by Yurij Luhovy, which have held me hostage since I looked at them, on the screen, sowing their question marks. I was told about the existence of these images by a friend who obtained them from a friend who, in turn, had gotten them a friend whom he hadn’t seen in ages, and whose voice he recognized during a radio interview addressing the burning question of Ukraine. I knew most of the actors in this summer theatre, posing in the silver prints as acrobats, bohemians, or celestial tramps – to use the term coined by Jack Kerouac, that great author–football player. I recognized one of them who, I know, is left-handed – re-educated many times by his teachers – and always shoots with his left eye to the viewfinder. But out of respect for their anonymity, to pique readers’ curiosity and test their knowledge of Quebec photography, I decided to hide the identity of the members of this commune of rebels and protesters against the system.

Was I really the privileged witness to the making of a historic document, stirred by my intuition about who each of these individuals would become? The only one I never met is the one who took these photographs that have so moved me. Far from being banal representations of the past, they are above all historical and programmatic. I was convinced that I was looking at irrefutable proof of the prehistory of the very first photographic groups in Quebec. Their creator absolutely had to tell me about his career, the circumstances under which he took the pictures, and why these photographs had slept in his archival boxes for almost sixty years. My curiosity was whetted and I wanted more. I know that there was more, that there were others that had gone unidentified, brilliant discoveries to dig out from Yurij Luhovy’s disorganized archives. He didn’t know it yet, but I wanted to put them in a book or publish them in a specialized magazine that would put them into perspective and recognize the value of their historicity, or else I would divert them into a book that would draw on the sensibilities of others – they would be a formidable counterpoint to the chapter devoted to the friends of my youth.

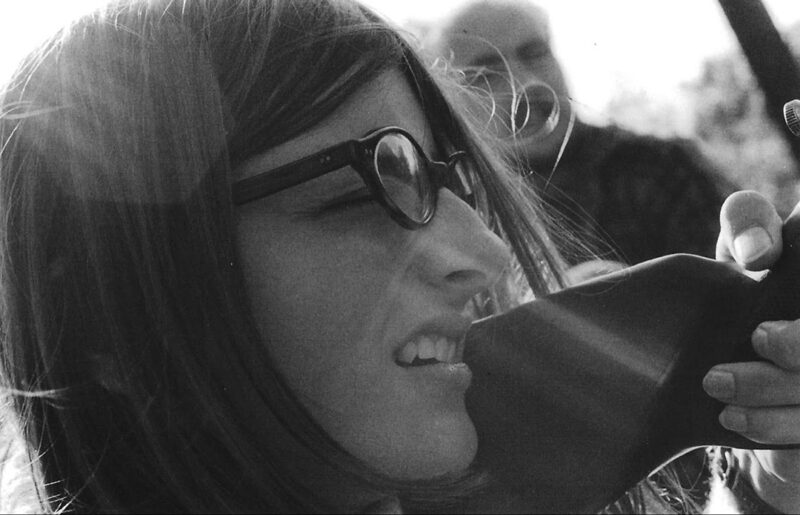

What appealed to me was the caustic eye of this filmmaker-to-be, these black-and-white photographs from a bygone age – their density, their contrast, their granularity, the tactility of the faces framed in close-up, in which nothing was happening, inhabited by the languor of the moment. I couldn’t help but be moved by this documentation glowing with the candour and innocence on the threshold of adulthood. I wasn’t seeing things – I was well and truly looking at a part of the history of photography that would be developed by a totally new generation who, bolstered by its times, its culture, nascent nationalism, and incipient leftism, would soon share the healthy rivalry of a collective passion for images.

Looking closely, you’d would think you were in Jean-Luc Godard’s Le petit soldat or Jean Pierre Lefebvre’s Le Révolutionnaire. Or you might be plunged into the vortex of an FLQ cell or inside the head of an association of miscreants. But this is a false impression, and I’m tempted to take up the slogan that a curator posted as a museum wall text: “On peut faire dire ce que l’on veut à une photographie” (You can make a photograph say anything you want it to). Yet, everything leads you to believe it: the clothing, the gun(s), the Quebec flag, the clandestine sites, and so on. The only “subversive” magazine that appears, however, called GoGo, looks more like it’s about the teenybopper music rampant at the time. The obligatory readings of all good budding Marxists – Mao Zedong’s Little Red Book, Pierre Vallières’s White Niggers in America, Karl Marx’s Capital, Friedrich Engels’s The Origin of the Family, Private Property, and the State – are nowhere to be found in the shots. It was more fun to hang out in the countryside.

I’ve written this text basically in one shot, stimulated by my collector’s curiosity, my wishful thinking as a historian and improvised author. The circumstances held out a mirror to me. I glimpsed my reflection there and melted into it, opening my eyes wide to my actions and no longer in contemplation, closing my eyes to the illusion of God. All the possibilities sprang up from these unheard voices. I don’t know who the handsome man in the photograph is, or the young woman – a lookalike for Anne Wiazemsky in Godard’s La Chinoise. These cool young men and women became my alter egos and changed the course of my life forever. They fuelled and changed the direction of my dreams, and kept me away from the temptation of my erratic actions. Translated by Käthe Roth

The author wishes to thank Maryse Pellerin, friend, author, and linguistic and literary editor.

Yurij Luhovy is a Canadian director, film editor, and producer born in Belgium in 1949 to Ukrainian parents. A graduate of Sir George Williams University (today Concordia University) in filmmaking and French literature, he has directed many historical documentaries, including Les Ukrainiens du Québec, 1891–1945, and has worked as an editor on films such as Alanis Obomsawin’s Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance. He is currently completing a documentary on his aunt, Halyna Stolar, a Ukrainian who fought against the Soviet and German occupations. Luhovy is the recipient of Queen Elizabeth II’s Diamond Jubilee Medal, the Ukraine Order of Merit, and the Shevchenko Medal from the Ukrainian Canadian Congress. He lives and works in Montreal.

Michel Campeau’s career stretches over five decades. Committed to an inwardness that goes counter to the medium and breaks with the formal conventions of documentary, he explores the subjective, narrative, and ontological dimensions of photography. His works have been exhibited and acquired by many institutions. He is represented by Galerie Simon Blais in Montreal, where he works and lives, and by Galerie Éric Dupont in Paris.