[April 10, 2024]

By Sylvain Campeau

Richard Baillargeon has come out with a new book. Published by Éditions Cayenne, Voyagements, parcours, passages et dérives des images covers a creative period encompassing everything he has produced over a four-decade career. In these pages we find, in addition to Baillargeon’s writings produced for the occasion, essays by the thinkers and guides Chantal Boulanger and Guy Mercier and an introduction by Suzanne Paquet, all three of whom have been close observers of Baillargeon’s work over the years (the essays are translated into English at the back of the book).

Voyagements : parcours, passages et dérives des images, Richard Baillargeon, Éditions Cayenne, 2023, 190 pages, colour and black-and-white images, 27,3 x 22,9 cm, cloth-covered hardcover, bilingual

This consequential tome, 192 pages long, is as imposing as Baillargeon’s oeuvre. He has chosen to offer a version of his work that doesn’t really fit the retrospective mould, although there does seem to be some sort of chronological order; the publisher’s website does in fact describe the book as retrospective in nature. But it’s subtle. Baillargeon’s reticence is understandably defensible: retrospective presentations can easily make artists a little anxious. As we can imagine, they might be loath to have their work presented as a complete and finished ensemble. To “trap” one’s production in a book that claims to be definitive is unsettling. It casts a shadow over possible future work, throws it into question a little, maybe even threatens it. Unfailingly, more works will come, and their maker will have to try to figure out how they can respond to what has already been established in this overarching source – the already-published retrospective book. Artists may feel a sort of imperative to equal that output.

But, at the same time, this type of publication is important. It brings together what has been scattered over the various times and spaces of an artist’s production. It offers an overview that can shed light on a career, show its coherence, its vagaries, its side roads. Such a book provides readers with a reference to the artist’s temporalities, long and short.

Baillargeon took inspiration from the double challenge of making new work and responding to the injunction to look back. For those who want to find their bearings and have a full vision of his production, he offers, in his “Notes on the Artworks,” two full pages on what he has done and where he has been. The effort obviously goes one better than a simple artist’s biography. Above all, it gives us new paths to follow; references to pages on which the works appear allow for a chronological and retrospective reading that leads us to browse fruitfully.

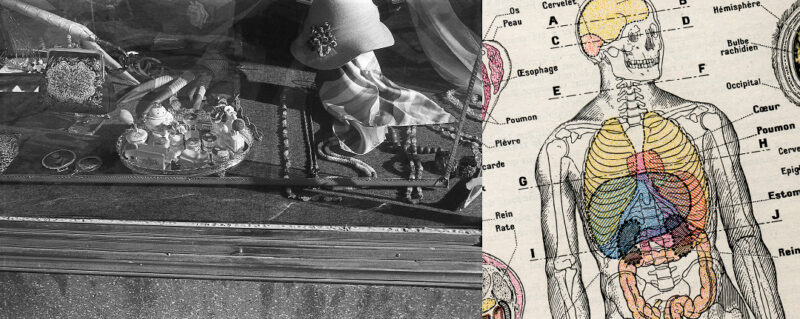

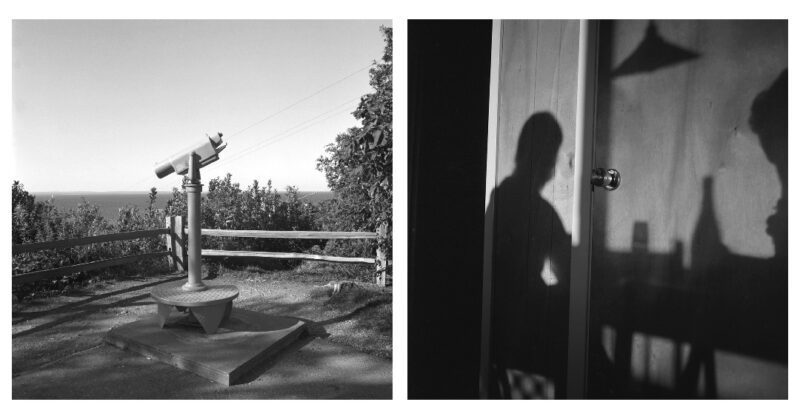

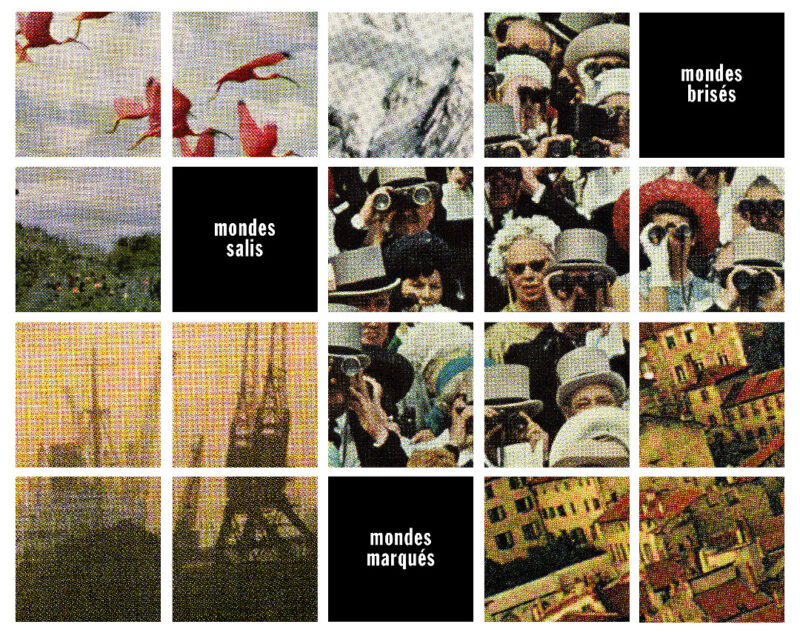

However, the book is an artistic performance in itself. The succeeding chapters organize the work in an order dictated by the process of making the volume. Baillargeon revisited and challenged his practice to offer a new, reflective vision, nourished by time and the wisdom of someone who is still searching to define himself and probe the reasons behind his impetus toward images. These reorganized bodies of work are brought together in chapters titled “Backwash,” “Backdrop,” “The Lost Way,” “Circles and Spirals,” “Fabulous Remains,” “Things Thrown There,” and “The Odysseys.” The texts that begin each one are expanded in the back pages to complement new versions of known works along with the brand-new works.

It is delicious to see these writings added to the textual presences extant in Baillargeon’s series. Groupings such as Le Cahier roman, Champs/La mer, Anticoste, and Promenades au couchant contained discreet, laconic, latent writings that indicated restraint, measurement of the image. Such insertions are still present, but they seem to fade slightly beneath the stratum of new texts with different intentions, a new layer added to the whole. For those conversant with Baillargeon’s work, the result is a sort of confused pleasure. We recognize familiar ground in many of the images. But then there’s a disruptive moment. They are no longer ensconced in the same setting. We gain new energy, our appetite whetted once more. Yes, they are the same photographs, the ones we have known and seen. And yet, something is new. Those images hadn’t revealed everything. It’s unexpected. From the country of knowledge, we have been deported to a new land. Rinse and repeat! Everything has shifted just a touch, reactivating the potentialities that we accept as already present and yet unprecedented. It’s disconcerting, but that’s how it is.

Only one explanation is possible. In this book Baillargeon has delivered a performance draws us into his reality: that of someone fascinated by (or wide-eyed about) images, who seems to have an inexhaustible reserve of possible meanings, eternally able to be reactivated. Translated by Käthe Roth

—

An anthropologist by training, Richard Baillargeon pursues an art career based on the encounter of photographs and text. His professional practice also extends to cultural management, exhibition curation, and writing. His work has been published in books such as Comme des îles (1991), Carnets de voyage (1994), Le paysage et les choses (1997), and Marges et chansons (2008), and been shown in exhibitions in Quebec, Canada, and abroad.

Sylvain Campeau contributes to many Canadian and European magazines. The author of seven poetry collections and several essays on the visual arts, he published Écrans motiles with Les Presses de l’Université de Montréal in 2022. As a curator, he has organized some forty exhibitions.