[October 4, 2023]

By Jean Gagnon

MOMENTA Biennale de l’image, Montréal

7.09.2023 – 22.10.2023

Masquerades: Drawn to Metamorphosis is the title of the 18th edition of MOMENTA Biennale de l’image – a title full of promise, as the notion evokes the possibility of many carnivals.

Masquerade is a device used in the visual arts, photography, film, theatre, and dance. There was once a pseudoscience, physiognomy, that sought to discern human character types by associating them with the features of animal faces, thus bringing the invisible into visibility. As a “tool,” it was employed by racists. The French painter Charles Lebrun also used animal faces to illustrate human passions. Speaking of metamorphosis, we can refer back to Les Métamorphoses du jour (1829) published by the great caricaturist Grandville. Masquerade has always been associated with what Mikhail Bakhtin called the carnivalesque – a style of writing that destabilizes the normal order of things, although, in the end, established powers and classes are able to maintain and reaffirm the social order.

The biennial’s curator, Ji-Yoon Han, expands the concept of masquerade to include the idea of mimicry. This, she explains, is the actual driving force behind the event, as it allows the theme to reach beyond the social and human world to summon the animal and plant realms, as well as technological aspects of the phenomenon:

Mimicry designates the aptitude to “do as if”: to imitate (do the same), which involves first and foremost the capacity to transform (unmake) oneself … [It] concerns human behaviour, the experience of all living things (animal and plant mimicry), and technological modelling (machine-learning mimicry). It situates us in the interstice between the self and the other, linking them and leading them to melt into one another.1

A sort of pan-metamorphism or pan-mimicry guided Han in her selection of works that also touch upon the question of variable identities – identity-related “frictions,” sometimes fictions. Such frictions are found in Séamus Gallagher’s work Mother Memory Cellophane (at the McCord Stewart Museum), embodied in a series of lenticular prints in which uncertain images shimmer. Reviving the iconic Miss Chemistry featured during the world launch of nylon stockings at the New York World’s Fair in 1939, Gallagher plays with the idea of synthetic skin.

The idea of masquerade is not obvious in the work of all twenty-three artists in the biennial. For example, at Dazibao, excellent works such as Carey Young’s The Vision Machine and Mirror System are more striking for the illustration of a female subjectivity framed by the male scopic regime than by an obvious masquerade. The second title reminds us that in male scopic regimes, masquerade may be a female strategy for articulating an identity as subject and spectator,2 but does it evade conformity, the dominant gaze, and reification?

Some works have undeniable qualities on their own and touch us even without a conclusive connection to the theme. For example, in Maya Watanabe’s delicately sensitive Liminal (at Occurrence), the camera points our gaze toward detailed observation of rich humus that is, we gradually discover, the site of a mass grave discovered in Peru. The piece evokes death and deception and, ultimately, Peruvian violence against Quechua communities.

Other works dwell upon postcolonial issues and refer to approaches to decolonization. To the distortions of colonial histories and Euro-centric domination, several artists hold up figures from marginalized cultures. For instance, Jeannette Ehlers’s video Moko Is Future (at Fonderie Darling) sets the tall, dancing figure of Moko, a masked character in a colourful costume on stilts, against the dull, grey, frozen setting of Copenhagen. Tuan Andrew Nguyen’s beautiful work Le spectre des ancêtres en devenir (at VOX) exposes a little-known after-effect of the love matches between Vietnamese women and Senegalese soldiers in Indochina. The result is a painful and touching family history, but also faces whose features express these intermixings of blood.

This Is Not a Metaphor (at Fonderie Darling) presents strangely erotic works by Valérie Blass: first, a photograph, Ce qui a déjà été vu ne peut pas être dévu, shows half-dressed models in suggestively form-hugging clothes; then, a sculptural installation, Le mime, le modèle et le dupe, presents the clothes seen in the photograph – emptied shells that retain the detailed body shapes. The strangeness arises from seeing skin without a body – sculptural representations that excite our wish to see when we are confronted with absence. It is an outstanding doubling of the photographic fact given that the thing portrayed is missing. Could this be the image-skin that Han talks about? It’s certainly the empty space that desire wants to fill in.

The shows at the Galerie de l’UQAM offer a happy juxtaposition through which the theme of masquerade is brilliantly made explicit in ironic or cynical parodies. Two projects, one by a Quebec collective and the other by a Mexican artist, show similar sensibilities in related satires on global issues in a world felt to be in decline. Despite their differences, they share a way of ironizing through the use of ancestral – but caricaturized – figures in their respective cultures. The Marion Lessard collective’s The Roman de Remort, or the inhumane, villainous fabliaux of the Ultimate Carnaval shows disguised figures in a forest, and we understand, through their garb and masks, the inspiration for medieval fabliaux. We are immersed in a tale that turns for the worse, in a Roman de Renard that is, as the title reminds us, corrupted. It’s obviously parodic and grotesque, a pessimistic carnival to denounce our treatment of nature. In Agüeros: Masquerade for the End of Time, Naomi Rincón Gallardo also calls upon disguises and masks. Her videos present a sort of visual syncretism, desperate or backward, dystopic, with characters who have fun dressing up in ways that recall the mythic figures of the Mexicas (the Aztecs). It’s a euphoric appropriation of pre-Columbian cultural elements reformulated and pieced together to denounce the cesspool of the present.

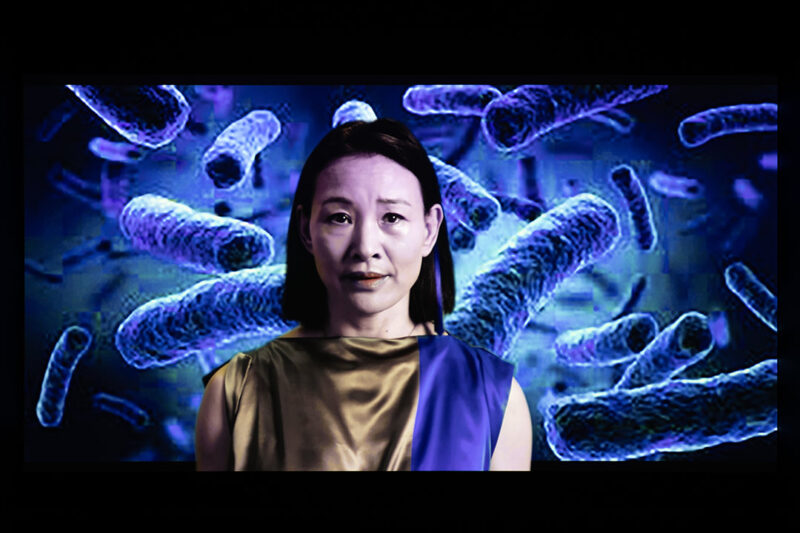

Masquerade has something in common with ceremony, with make-believe, and with duplicity – far from the truths of identity. Today, when the experience of identity is apparently defined as the personal truth of each individual, this biennial forces us into further circumspection. Lynn Hershman Leeson’s video Logic Paralyzes the Heart (at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts) addresses the artificial identity of a cyborg. Throughout her work since the 1960s, Hershman Leeson has used masks and personae to explore “identity, reality, and truth.”3 And since the 1980s, she has been increasingly questioning the connections between personal identity and social and cultural structures, the digital surveillance environment, and the military-industrial complex.

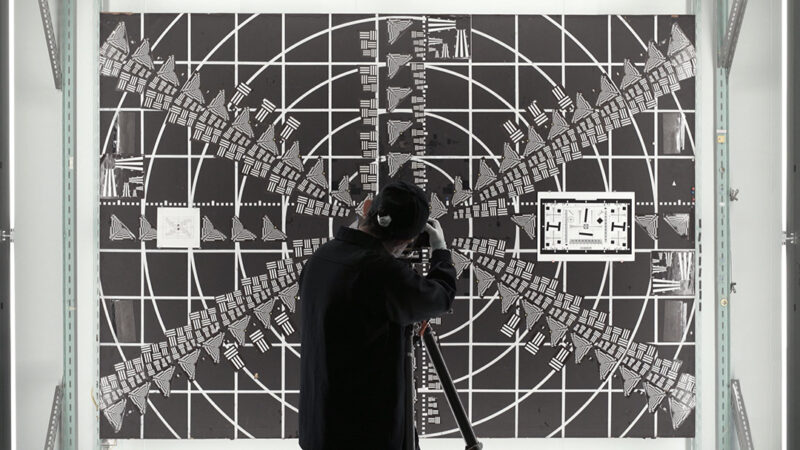

Another work, Hito Steyerl’s SocialSim (at the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal), presents an allegory of the digital and virtual worlds modelled from data on police violence. This socio-political critique (its title is a play on the word socialism) is also a fable about art, artifice, avatars, and artificial intelligence linked to the coming carnival of simulations. Such simulacra are increasingly both entertaining and alienating us, but the artists are keeping an eye out, as MOMENTA shows.

2 See Mary Ann Doane, “Film and Masquerade: Theorising the Female Spectator: Mary Ann Doane on the Woman’s Gaze,” Screen 23, no. 3–4 (Sept.–Oct. 1982) 74, 88, full article available at https://eurofilmnyu.files.wordpress.com/2014/01/doane-film-and-the-masquerade.pdf.

3 Moira Roth and Diana Taini, “Interview with Lynn Hershman, in Lynn Hershman, Chimaera monographie no. 4 (Montbéliard Belfort, France: Éditions du Centre international de création vidéo, 1992), 108 (our translation).

Jean Gagnon is an exhibition curator and independent art critic, who has been a curator at the National Gallery of Canada, director of the Daniel Langlois Foundation, and director of collections at La Cinémathèque québécoise. The author of Vidéocaméléon, devoted to video art in Quebec from 1972 to 1992, he is currently completing a book on language and rhythm in Michael Snow’s work.