[August 30, 2023]

By Érika Nimis

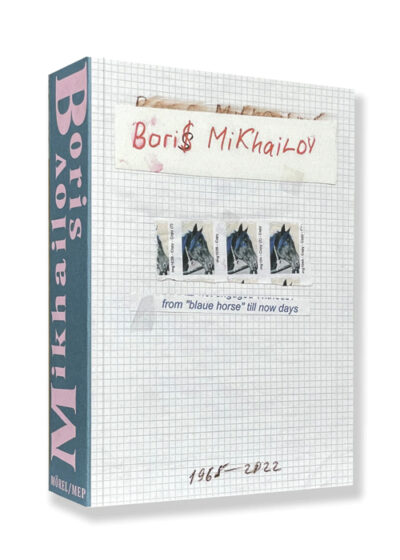

The tone of this book by the photographer Boris Mikhailov (born in Kharkiv in 1938) is established on the front cover, which looks like a page torn from a notebook, with scribbles, stains, and things crossed out. This “catalogue irraisonné,” bringing together Mikhailov’s twenty-seven projects produced over the last fifty-seven years, pays tribute to his creative process in “permanent revolution,”1 which has inspired generations of photographers2. In fact, it is difficult to fix his work, to encapsulate it on paper, because he sees “low quality” as a “means of subversion.”

Boris Mikhailov, From “Blaue Horse” Till Now Days 1965–2022, Paris, London, Maison européenne de la photographie, Mörel Books, 2022, 576 pages.

Published in 2022 to accompany a retrospective at the Maison européenne de la photographie (MEP)3, and already in its second edition, this bilingual (English and French) catalogue almost six hundred pages long was designed and edited with input by Vita Mikhailov (Boris’s wife), the publisher Mörel, and the curator Simon Baker, director of MEP since 2018. From “Blaue Horse” Till Now Days gives readers a chance not only to survey, study, and give their full attention to Mikhailov’s prolific production but to grasp the great coherence of his artistic approach over the years.

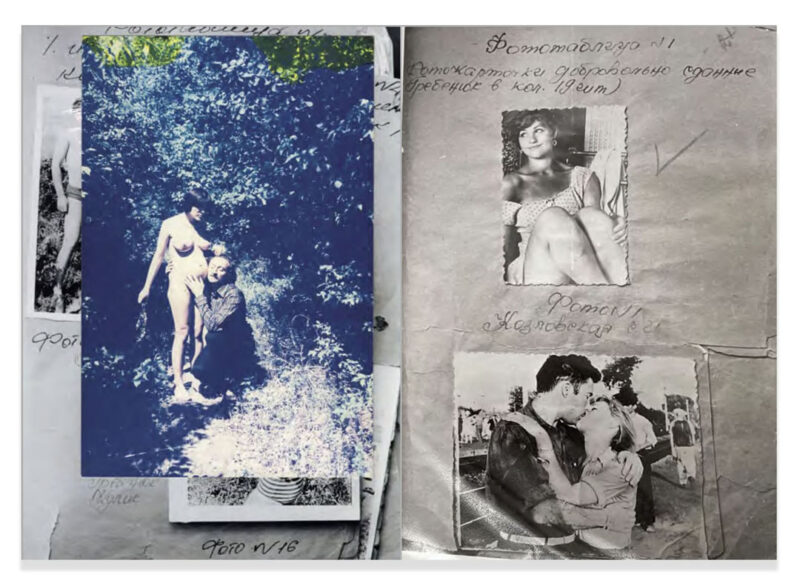

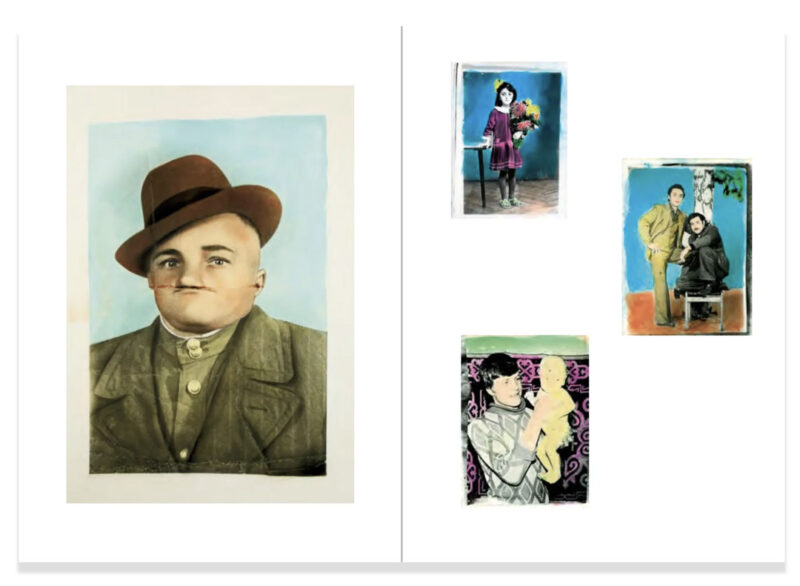

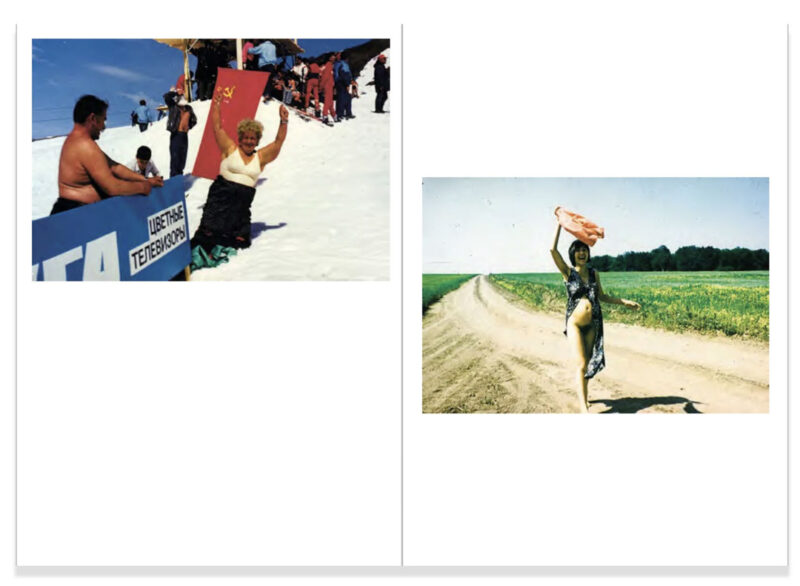

Where does the book’s title come from? The explanation is given in a sort of photographic preface, with full-page reproductions of a series of intimate black-and-white shots taken during the 1960s by a group of friends in Kharkiv who called themselves “Blue Horse” (to which are appended, as a reflection, a few of Mikhailov’s colour photographs). These images would result in their incarceration for acts of “debauchery.” “In the Soviet Union,” Mikhailov writes, “undesirables were often accused of pornography or declared mad.” During this period, the young Boris, an engineer and photographer in a factory, began to take nude pictures of his wife. The KGB found out about them in 1968, and he barely avoided prison.

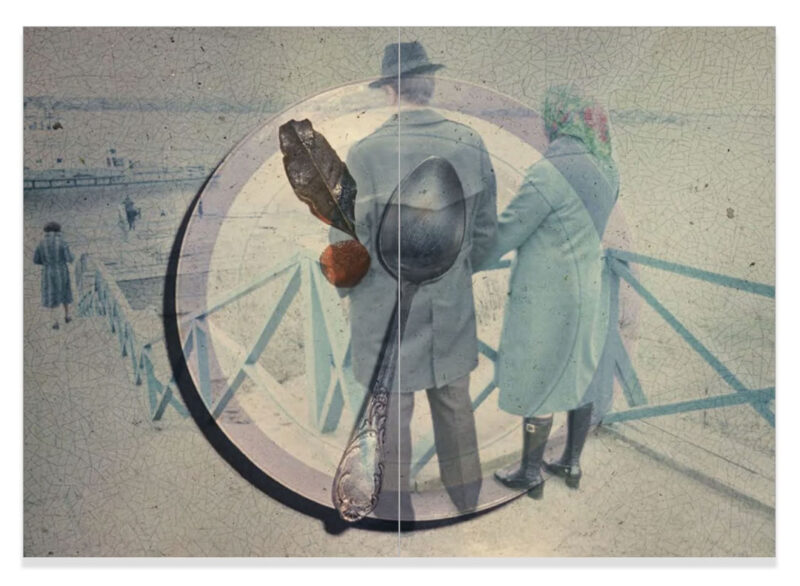

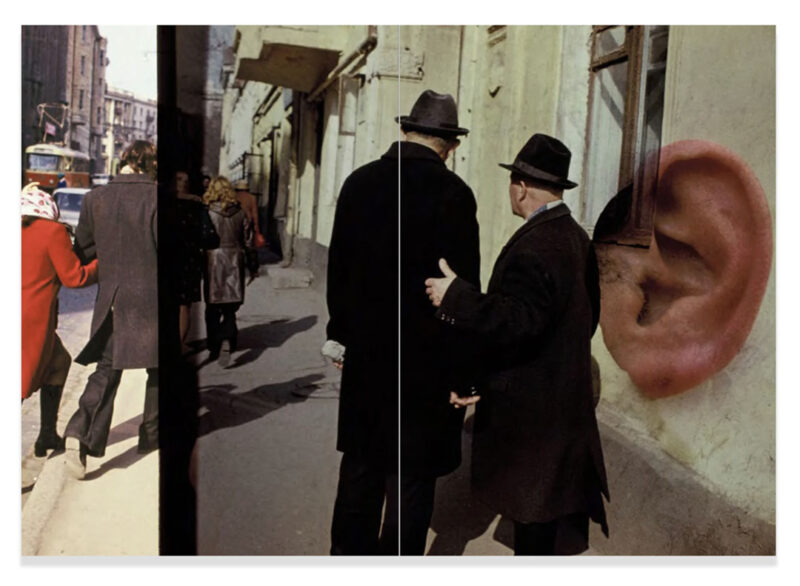

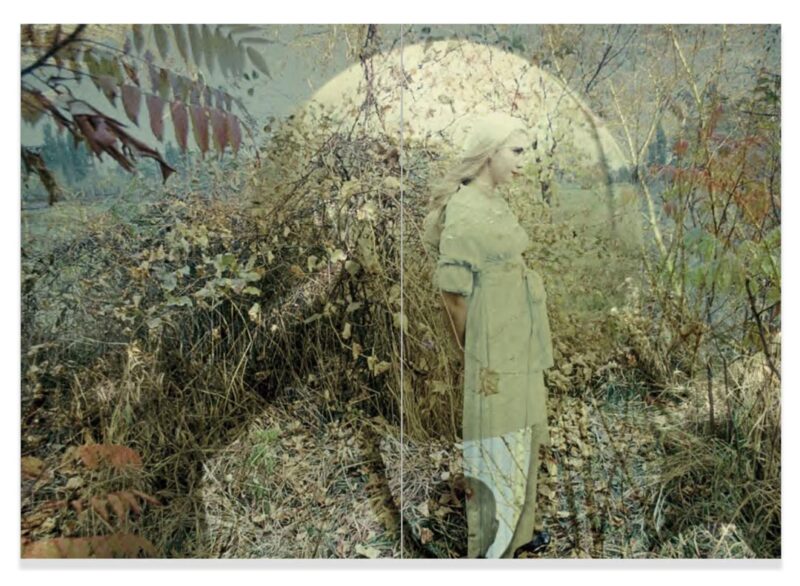

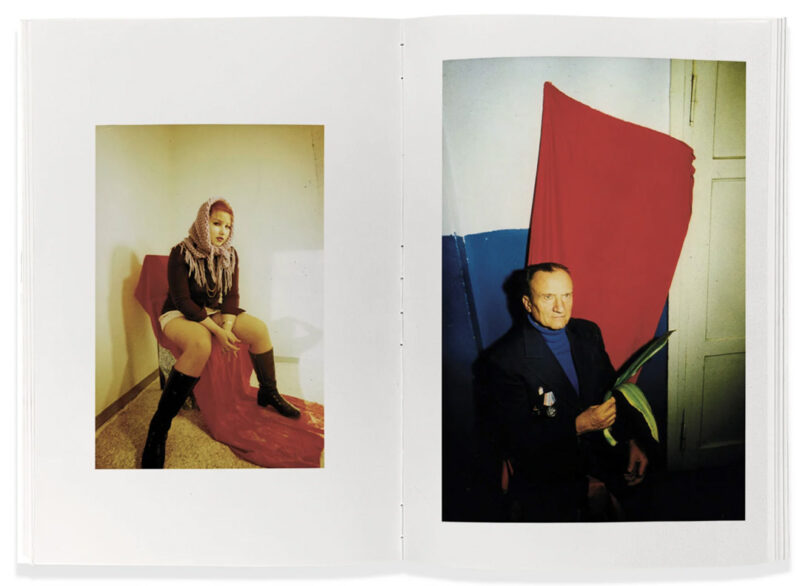

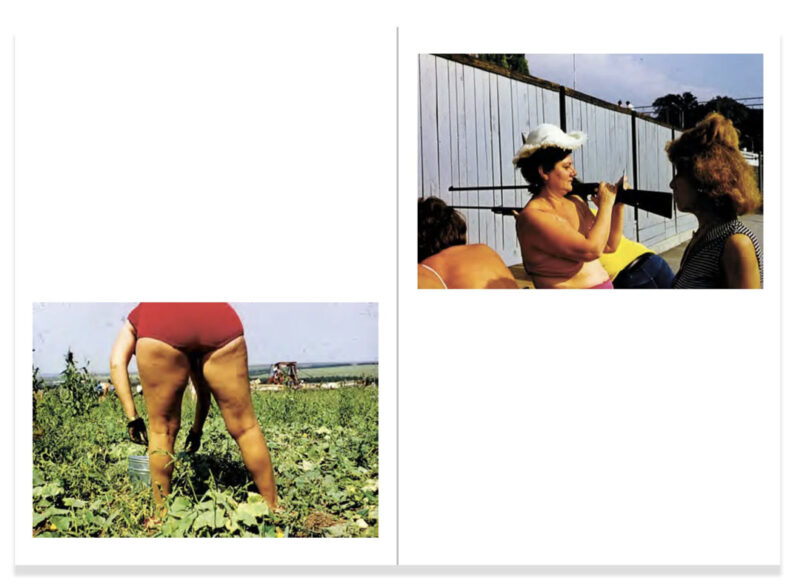

In an extraordinarily rich body of work that resists categorization, Mikhailov has constantly defied the restrictive codes of Soviet photography and the heavy heritage from that period up to the present. He deliberately exploits technical mishaps and other glitches that reflect the depths of his thought, sometimes transcribed into the photographs, and uses ridicule and pseudo-amateurism as shields against censorship.

The series from Mikhailov’s Soviet period, produced under the constraints of censorship and material shortages, are just as powerful in the book as in the retrospective – if not more so – because it offers the leisure of private consultation. I’m thinking in particular of the images from the original series Yesterday’s Sandwich (1960–70), which opened the exhibition in the form of a slide show – “a random assemblage of elements . . . reflecting the dualism and contradictions of Soviet society” – superbly summarized in a section of the catalogue.

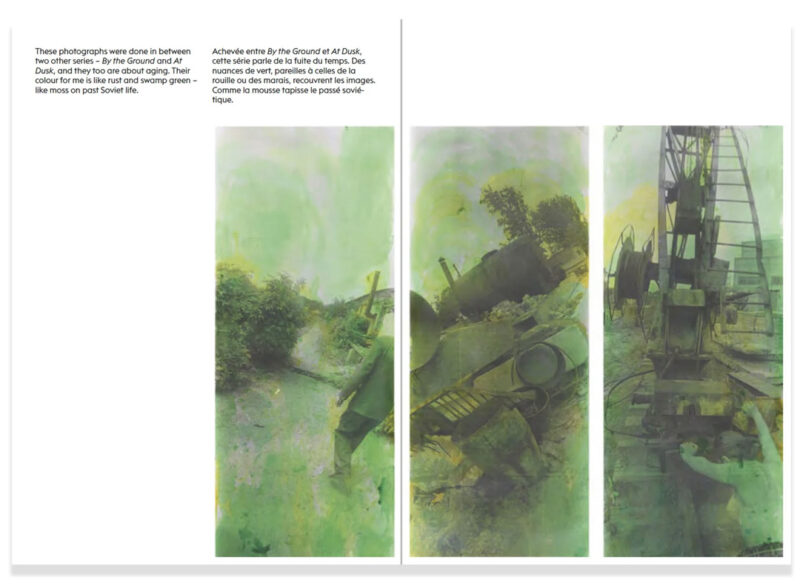

The quality of the layout and printing respects and even magnifies all the imperfections that are Mikhailov’s stock in trade and allows us to immerse ourselves in the rich complexity of his work, as we see again – or for the first time – emblematic series such as Red (1968–75) and At Dusk (1993). The book also allows us to fully appreciate more recent series from the post-Soviet period, again combining several media in an experimental mode, such as Theater of War, Second Act, Time Out (2013–14), a chaotic chronicle of the Maidan revolt. “For me,” he writes, “the main mood of this series is the tension, the anxiety in the air. Maybe it was the anticipation of war.” The series Parliament (2015–17) judiciously exploits the televised transmissions of tumultuous parliamentary debates, “a metaphor for the confusion and mistrust that reigned in the political climate in the early stages of the Ukrainian conflict” in 2014. Conceived as a private journal “written in photography,” the series Diary 1965–2022 brings the entire body of work together at the end.

Mikhailov’s enlightening introductions to each series give additional insight into his world. A booklet containing translations of the handwritten notes in the series Viscidity (1982) and Unfinished Dissertation (1984–85), as well as essays by Baker, Laurie Hurwitz (curator of the exhibition), and the artist Leigh Ledare (a friend of the Mikhailovs’), complements the catalogue. Translated by Käthe Roth

2 Since the 1970s, Kharkiv has been home to a major photographic movement, the Kharkiv School, of which Mikhailov is one of the leaders.

3 For a review of the exhibition, see “Érika Nimis, Boris Mikhailov, Ukrainian Diary,” Ciel Variable, cielvariable.ca/boris-mikhailov-journal-ukrainien-erika-nimis/.

A photographer, historian, and publisher, Érika Nimis, who specializes in the history of West African photography, is an associate researcher in the Art History Department at UQAM. In 2020, she started a photographic project on Ukraine, the home country of her paternal grandmother.