[November 9, 2023]

By Michel Hardy-Vallée

As a critic, you’re expected to impartially hand out scorecards with stars, thumbs, or tomatoes to prevent customers from wasting their hard-earned money on “bad” works. “Criticism” implies judgment, but more in the sense of an appraisal than a court order. In the literary context, we tend to associate criticism with gushing reviews or hatchet jobs, but it consists, rather, of using judgment to perform a variety of tasks, from the correction of improperly transcribed texts to the explanation of their historical significance. When I write about photobooks, I do so from the standpoint of enthusiasm and curiosity, and not from a position of pure objectivity. At the invitation of Ciel Variable, I am reviewing this Michael Flomen’s book, in which my name appears among the contributors, because I can explain some things about it and leave to you, readers, to judge whether or not you should part with your hard-earned cash for it.

Michael Flomen, Photograms and Photographs 2020–1970, 2022, Munich, Hirmer, 22,9 x 29,2 cm, hardback, offset lithography, 300 pages.

Michael Flomen is offering a retrospective look at his career, as the reverse-chronological subtitle subtly implies. It came to him because it highlights the fact that this is a 2020 look at half a century of work, and on this point many historians will agree with him – at least those who do not pretend to write without having a standpoint. Originally conceived as an exhibition project for the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, it was put on hold by the pandemic and further developed into a book project with the help of Robert Hébert (Éditions Cayenne), then finally published and distributed internationally by Hirmer/University of Chicago Press.

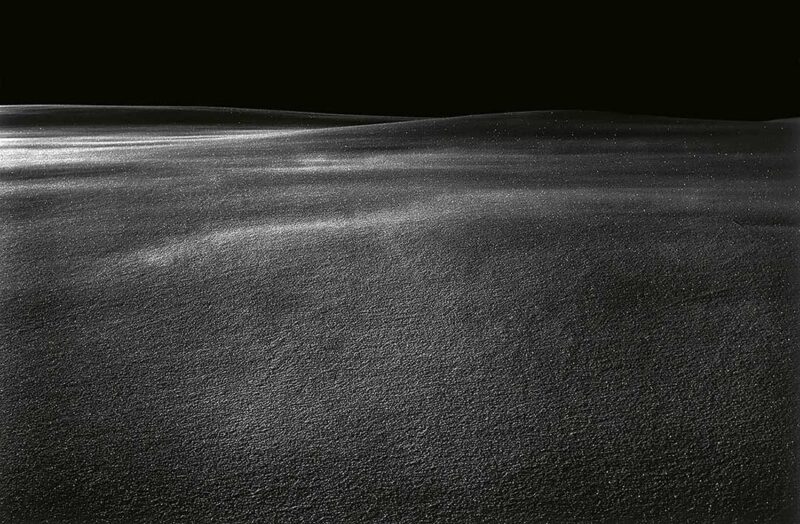

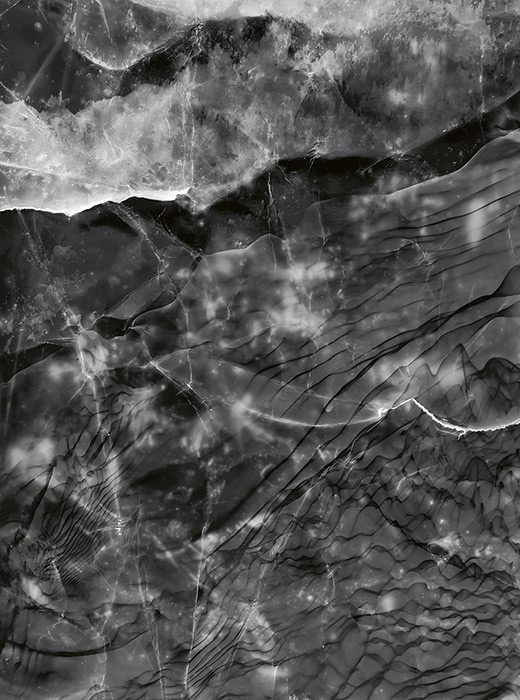

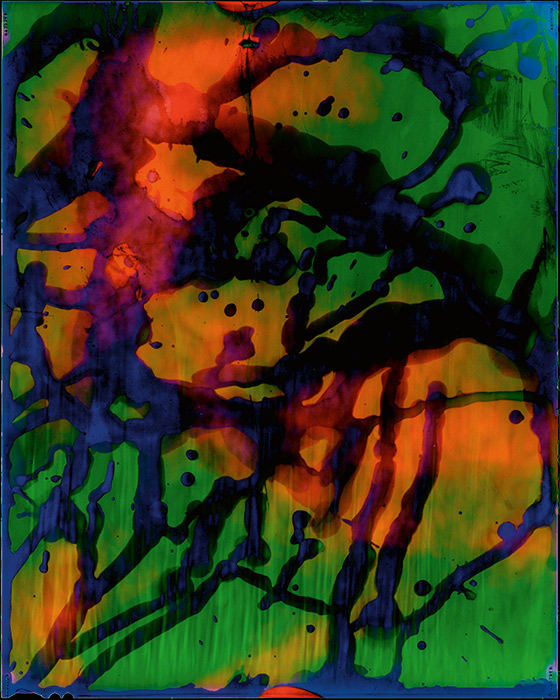

Starting from the back of the book and flipping toward the front, we can follow Flomen’s career chronologically as he evolves from a subject-oriented photographer (the street, people, or places) to an image-oriented one. Or we can read the book in its usual sequence, beginning with his large-scale photograms and excavating through his work, layer by layer: first, his experiments with alternative sources of light (fireflies being the most technically challenging) and unorthodox processes (letting polluted sources of water affect photographic paper); then the turning point of his snow photograms, being neither strictly positive nor negative images (compare this to Henry Fox Talbot’s contact prints of lace fabric c. 1845); last, his street photographs, in which the specificity of identities and situations is slowly sucked out by way of abstraction, sometimes evoking Ralph Gibson or Nathan Lyons. Throughout, essays by contributors (critics, academics, journalists, partner) complete the historical and personal contextualization of his career and relate his creative work to the practicality of his craft as a professional darkroom printer for other artists.

Flomen’s photograms can be enormous in size, the latest being taller than a person and almost as long as an automobile. Not being enlargements, they are grainless and thus show very fine tonal gradations and presence; the reproductions in the book give an idea of their overall composition and form, but it’s the enlarged details opening each section that best show their tonality and texture. The cavernous lair in which Flomen produces them is equally awe-inspiring, populated by custom-built trays and drums that require gallons of processing solution and are flanked by skyscraper-sized enlargers. However, the abstract nature of most of his work makes the question of scale within his images a wilful indetermination: some of the snow photograms can suggest the vastness of a faraway planet apprehended from the standpoint of a flyby satellite, whereas the organic shapes of his chemical experimentations can also suggest the microscopic world of paramecium and other protozoa. Impressions of the fireflies’ flash also function out of scale, as their direct trace (their index, if you must use the agreed-upon photographic theory terminology) is actually larger than themselves – a fact that, I hope, can send some of my colleagues into a well-deserved intellectual tailspin.

Experimenting with light-sensitive materials is a hallmark of modernist photography that falls under the umbrella of the New Vision. László Moholy-Nagy, Man Ray, and Alvin Langdon Coburn are the international prototypes; in Quebec, we should pay more attention to the work of Gordon Webber, Jauran (Rodolphe de Repentigny), and Robert Millet until the late 1950s for continuity with this approach. By the 1970s, when Flomen began his career, these direct manipulations of materials, light, and chemicals were mostly reduced to the fad of the Sabattier effect, also incorrectly known as “solarization.” It involves turning on the white lights while the print is still processing in the developer tray, thus messing up the tones in an easy-to-teach darkroom party trick. Flomen thus hails back to the modernist experiments with the materials of analogue photography, but he brings to them a less rational mind that embraces complex randomness.

As to my own quantum entanglement with Flomen as collaborator and critic, what am I credited for in this book? Appropriately, for my corrections.

Michel Hardy-Vallée is a historian of photography and Visiting Scholar at the Gail and Stephen A. Jarislowsky Institute for Studies in Canadian Art, Concordia University. His research is concerned with photography books, visual narration, interdisciplinary practices, and the archive, in the contexts of Quebec and Canada. He is currently working on a monograph about John Max.