[November 29, 2022]

By Cheryl Simon

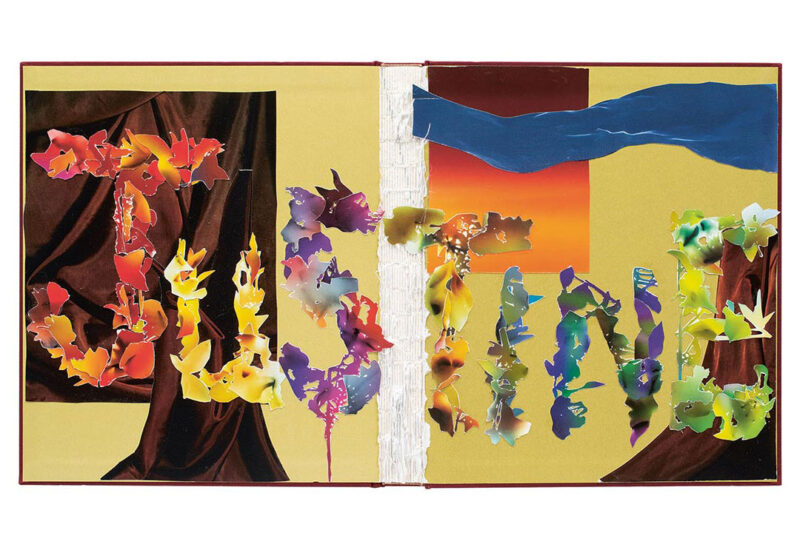

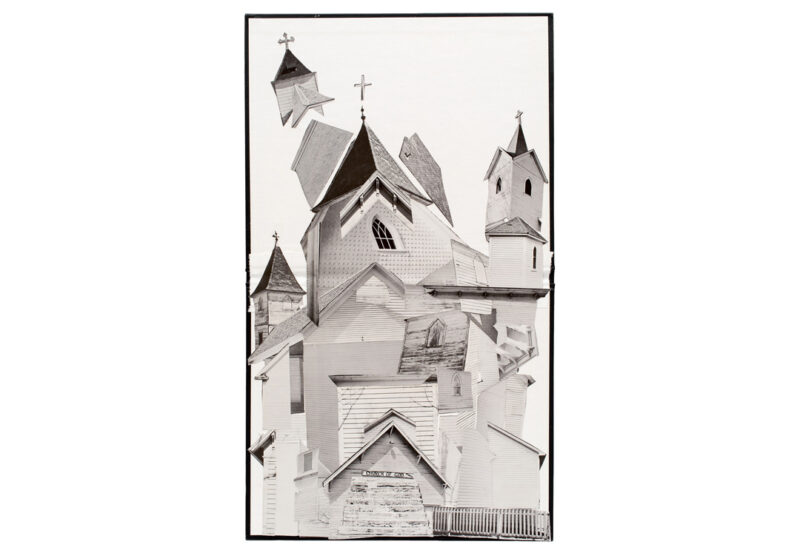

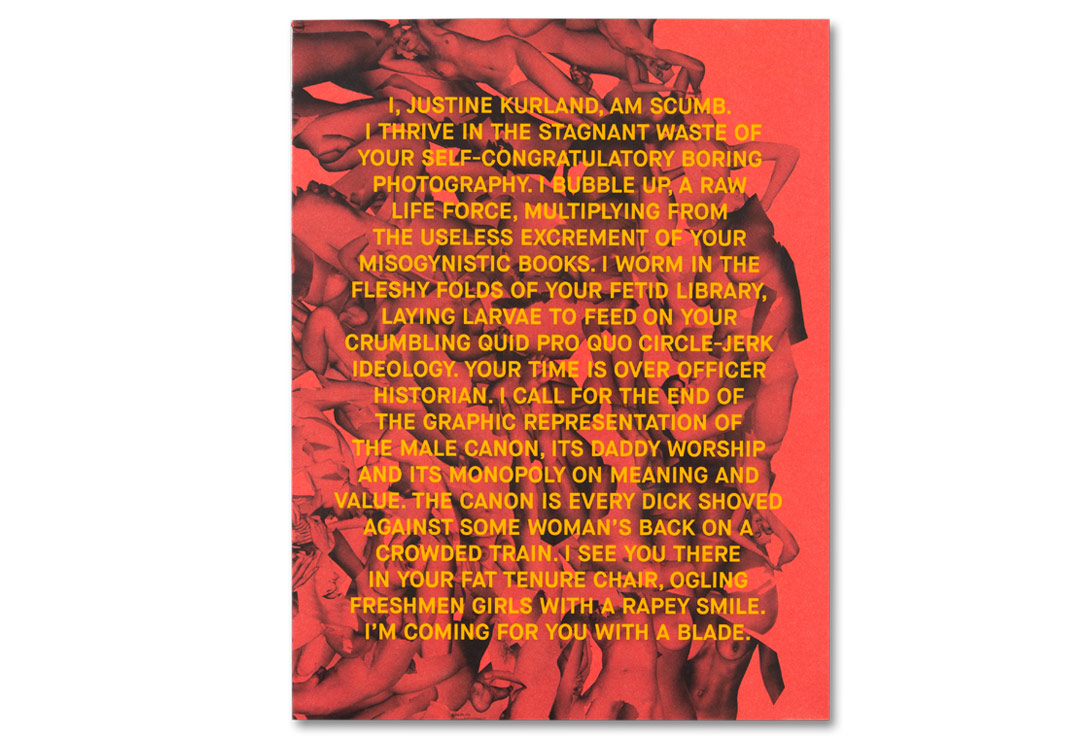

Justine Kurland’s recent collage-based project represents a new, distinctly material direction, as she is otherwise known for innovative and charged documentary photography: found and staged and stunning tableaux of girls and women, and American life on the edge. With SCUMB Manifesto, Kurland pays homage to Valerie Solanas’s sensational SCUM Manifesto (1968) – SCUM being an acronym for Society for Cutting up Men –, adding a silent B to the acronym to indicate that the act of cutting in this instance is exercised on men’s books rather than on men. Bold, radical, and playful, SCUMB Manifesto borrows something of the spirit of the original, but whereas the cutting reference was a literary device for Solanas, for Kurland it is literal. SCUMB Manifesto presents collages made out of materials cut from her collection of photography books. An incisive reworking of the canonical texts of Western photographic art, she cuts into, across, and through the white, male vision that has defined much of the history of photography.

Justine Kurland, SCUMB Manifesto, London, MACK, 2022, 24.5 x 32 cm, perfect bound, offset lithography, 282 pp.

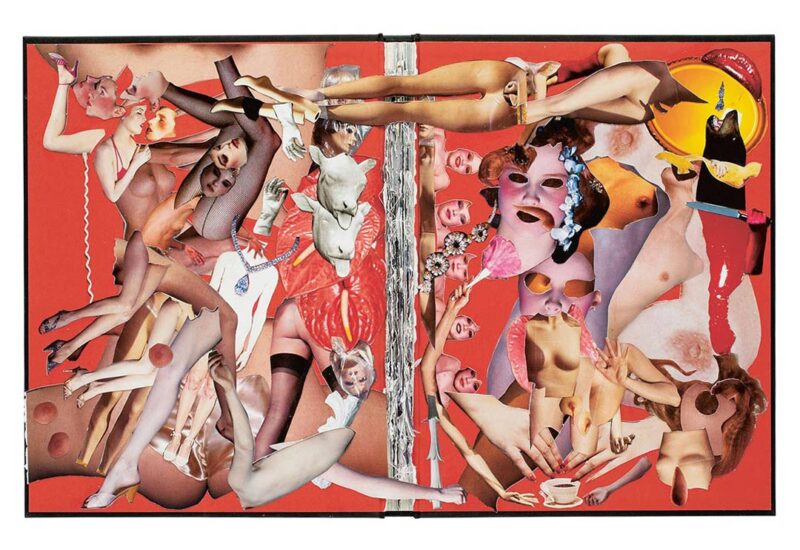

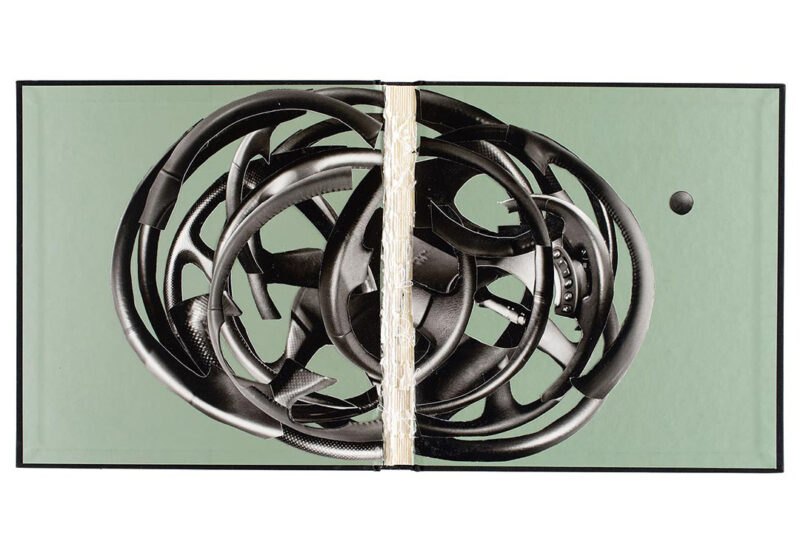

First exhibited in 2021 as a series of sixty-five one-of-a-kind collages assembled on the covers of the books from which the respective raw materials were drawn, SCUMB Manifesto returns the stolen imagery to book form, albeit substantially and irreversibly changed. Featuring 116 plates, it’s a much bigger project than it was before. So too, membership in the “Society for Cutting Up Men’s Books” has grown since it was established. By turns introspective, poetic, performative, honorific, and erudite, essays by Renee Gladman, Mariana Chao, Catherine Lord, Ariana Reines, and Kurland deliberate on “the cut” as a form of feminist reclamation: a strategy of resistance to the near-inexhaustible enthusiasm for the objectification of women in representation.

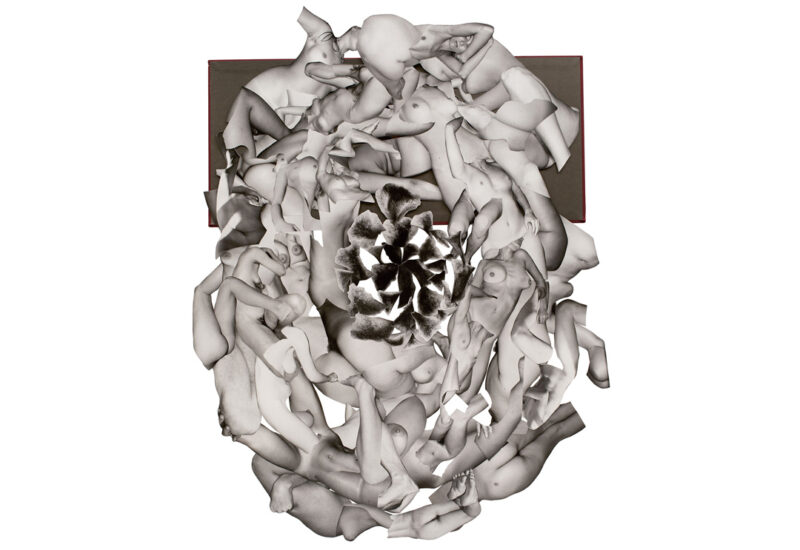

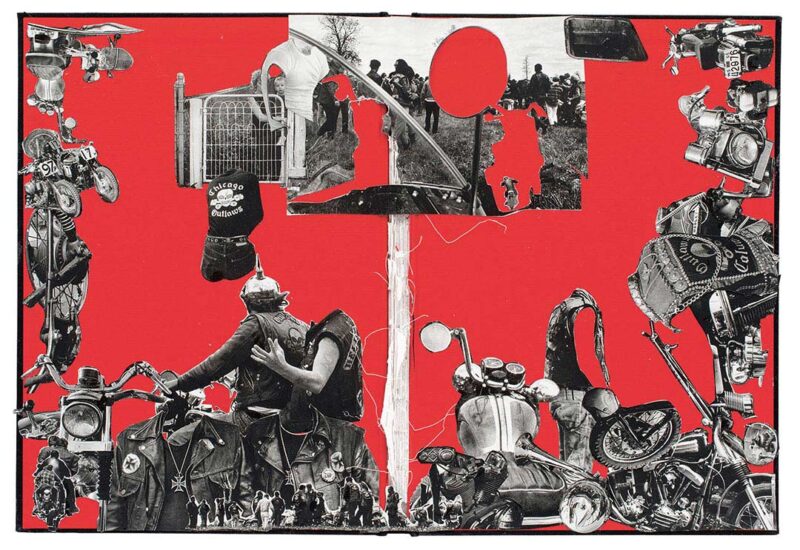

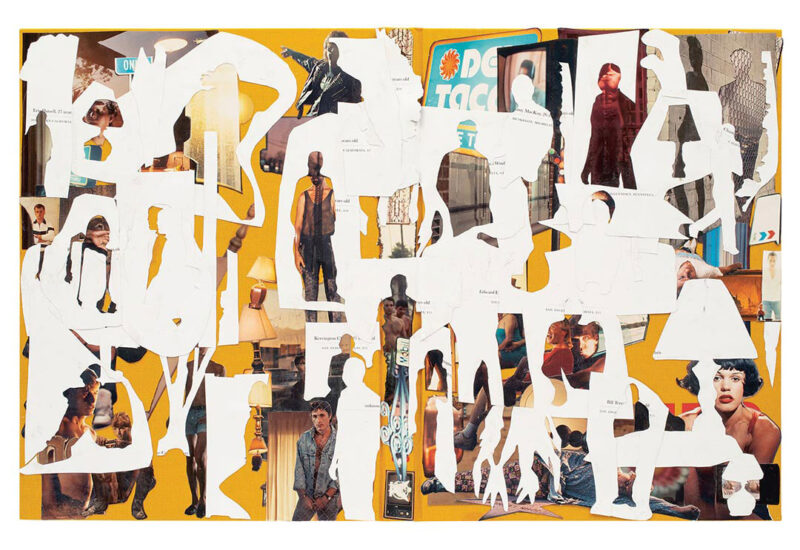

Although the authors of the photographs from which Kurland’s collages are drawn are not named, the title of each assemblage refers or alludes to their iconic projects; in most cases, the signature styles and primary interests of these photographers are strikingly apparent. Indeed, the works in SCUMB Manifesto aim to distil the essence of each donor’s project, in the process revealing something of the psyche from which it sprang. Harry Callahan’s obsessions are made crystal clear in the preponderance of nude backsides that populate Kurland’s Eleanor tableau, and Edward Stieglitz’s kinks are exposed in the undulating hands that form her homage to Georgia O’Keeffe. The Bike Riders obviously takes Danny Lyons’s book and preoccupations as their source, and Richard Avedon’s imperious authorship is clearly conjured by the emptied 8 x 10 contact sheet frames that fill Kurland’s Portraits works.

In Portraits (Negative Space), Kurland cuts the figures out of each original image and fills the clear space left behind with layers of other emptied frames. The effect is to suggest that the subject-objects of this highly stylized body of work are largely interchangeable – equally and predictably famous, odd, or sensational. To similar ends, Portraits (Additive Space) leaves a clutter of accoutrements behind. Things such as rattlesnake skins and animal teeth, belly buttons, penises, freckled hands, and honeybees clinging to bared skin stand in for the singularity of human lives.

Among others, Tod Papageorge, Lee Friedlander, Guy Bourdin, Helmut Newton, Philip-Lorca diCorcia, William Eggleston, and Stephen Shore make appearances in SCUMB Manifesto, and a substantial number of the collages made from their books feature cut-up body parts, mostly, but not exclusively, of the female type. Dismembered heads and arms, legs, breasts, chests, and pubic hair are fitted into suggestive and stunning configurations. Some spell out names; others partake in exuberant, lesbian orgies and other forms of sexual pageantry. More often than not, the parts are enfolded into splayed-out scenes of everyday life, human parts cohabiting with car parts, foodstuffs, and consumer goods, streaming along like debris after a storm.

To anyone who has studied photography in the last fifty years, SCUMB Manifesto will generate mixed feelings. In recent interviews, Kurland acknowledged that project travels across some very emotionally charged terrain. The images taken as source material were formative for her, as they were for most of us. In part, the project is a reckoning; in part, an evisceration. Either way, it is essential work. Amid the cacophony of mostly male-defined representational schemes, SCUMB Manifesto has carved a different and perhaps more authentic voice for Kurland, and so it has opened a space for new readings, revisions, and reclamations, and new voices within the photographic canon.

Cheryl Simon is an academic and writer whose current research interests include algorithmic art and internet culture, photography and the archive, media archaeology, and changing modalities in screen-based art practices. She teaches in the MFA-Studio Arts program at Concordia University and in the Cinema + Communications Department of Dawson College, both in Montreal.