[December 14, 2022]

Ukrainian Diary

Maison européenne de la photographie, Paris

7.09.22 – 15.01.23

By Érika Nimis

The exhibition Ukrainian Diary, presented at the Maison européenne de la photographie (MEP), is the largest retrospective ever devoted to the abundant and iconoclastic work of the photographer Boris Mikhailov, which resonates with more than a half-century of contemporary Ukrainian history. The exhibition is set out chronologically, on two floors – some twenty series – accompanied by Mikhailov’s own commentary.

Mikhailov was born in Kharkiv in 1938, and he grew up under Stalinism. The first capital of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic (1919–34), Kharkiv was a culturally effervescent city, with an art avant-garde that would be decimated during the Stalinist purge of the 1930s.

The 1960s, under Khrushchev, saw the emergence of numerous photo clubs for amateurs. One of them, Vremya (Time), formed around 1970, brought together a group of photographers who set about countering the dogmas of socialist realist photography embodied by the magazine Sovetskoe Foto. This group gave rise to the Kharkiv Photography School, of which Mikhailov is the best-known representative.

In the late 1960s, Mikhailov became a photographer by accident, as he was chosen to record life in the state factory where he was working as an engineer. When, in 1969, the KGB discovered that he was using the laboratory in the factory to print nudes of his first wife, he was immediately sacked and barely avoided prison. This traumatizing experience transformed him into a dissident artist who made photography a tool for emancipation and the streets of Kharkiv the scene for his subversive experiments.

To get around censorship, he first photographed his close circle. Nudity of bodies (his wife’s, his friends’, his own), rebellious and joyful, was omnipresent in his work, as was ridicule – the best weapon for resisting the ambient gloom and inertia.

Photographic experimentation is key to Mikhailov’s creative process. A versatile artist, his early love was filmmaking, and his practice stands out for his use of slide shows, seriality, and the performativity of photographed bodies. Despite the material and ideological constraints of the Soviet era, he literally took photography out of its frame, breaking all conventions; due to shortages but also by choice, he favoured poor-quality supports, sometimes plucking them from the trash. His prints were blurred, stained, low quality (Black Archive, 1968–79), sometimes printed several times on a single sheet of paper, in a small format and therefore easy to conceal (his studio was frequently visited by the KGB) or shown in hastily organized private exhibitions in colleagues’ and friends’ apartments.

Starting in the 1980s, impelled by the “powerful energy of desperation,” Mikhailov asserted his subjectivity. He explored every aspect of the book format in the series Viscidity (1982), Unfinished Dissertation (1984–85), and Diary (1973–2022): he glued his “obsolete, monotone” images into loose-leaf binders, enhancing them in various ways (colouring drawing, collage, scratching) and with written reflections that include words crossed out and underlined, as if they were a draft. In one of his exhibition texts, he recounted how one day, by chance, he had “sandwiched” two colour slides, giving rise to the poetic and baroque Yesterday’s Sandwich (1960–70), a ten-minute slide show to the musical accompaniment of the introduction to Dark Side of the Moon (Pink Floyd, 1973), in which the private and public spheres were surrealistically and colourfully foreshortened.

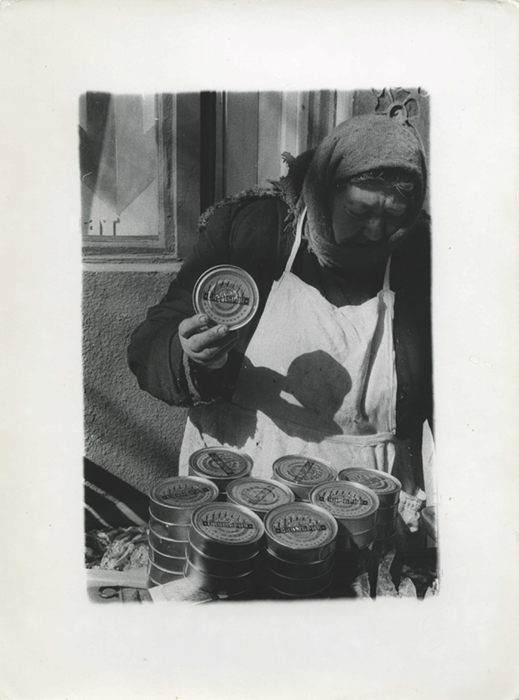

In the series Luriki (1971–85), Mikhailov, a studio photographer by day, diverted a practice popular in the USSR until the 1980s (due to inaccessibility of colour film): colourization of private portraits, which he saw as highly subversive. Presented in the same gallery, Sots Art (1975–86) pushes the critique of Sovietism even further by transforming journalistic photographs into tragi-comic farces, including one of men wearing shirts of a toxic yellow, gas masks on their heads, under a portrait of Lenin with red-tinted lips.

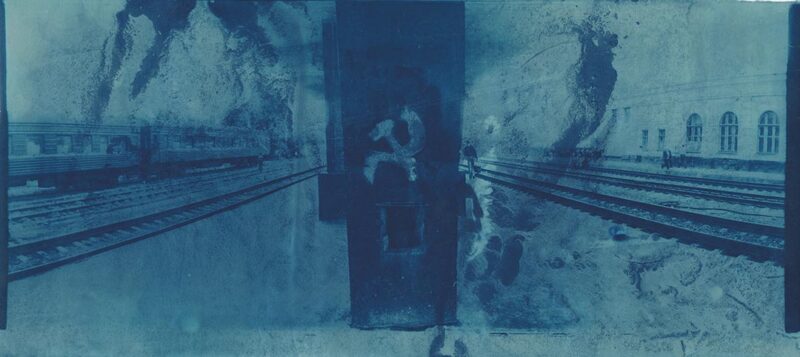

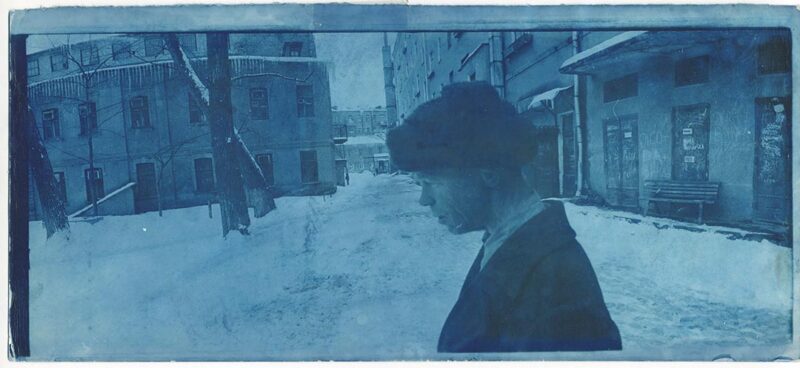

Throughout Mikhailov’s body of work, colour is meaningful. Red (1968–75) revisits the state-organized communist parades by highlighting the red omnipresent in that society – even the acne on teenagers’ faces. The panoramic views colourized with cobalt blue in the series At Dusk (1993) evoke the “dusk” into which Ukraine was plunged after the collapse of the USSR. At that time, Mikhailov was living in Berlin, where he was becoming known internationally and completing, as an acknowledged maverick, an extraordinary body of work. The series produced during this period were characterized by the abandonment of black and white and the use of very large formats.

A wall text at the entrance to the MEP warns the public of the disturbing nature of some images dealing with nudity and poverty. Holding up a magnifying glass to the social upheavals roiling his country, Mikhailov raised awareness with the series Case History (1997–98), which he called his “requiem”: some four hundred raw portraits of unhomed people whose lives have been destroyed. By photographing the harshness of human misery, he was not simply seeking to overstep photographic ethics, as critics sometimes accuse him of doing. He was remaining faithful to the “negative aesthetic” for which he has been advocating since the beginning of his career – an aesthetic that continues to influence the new generations of the Kharkiv Photography School. Translated by Käthe Roth

2 See https://ksp.ui.org.ua/.

3 I borrow this idea from the historian of photography Nadiia Bernard-Kovalchuk, who is currently conducting research on the Kharkiv Photography School.

A photographer, historian, and publisher, Érika Nimis, who specializes in the history of West African photography, is an associate researcher in the Art History Department at UQAM. In 2020, she started a photographic project on Ukraine, the home country of her paternal grandmother.