[October 5 2022]

By Ariane Noël de Tilly

The Milk of Dreams

59th edition of the Venice Biennale

23.04.2022 – 27.11.2022

When she wrote her children’s book The Milk of Dreams, the Mexican surrealist artist Leonora Carrington certainly had no idea that one day the book would become a major source of inspiration for the exhibition curator Cecilia Alemani, who borrowed its title for the 59th edition of the Venice Biennale. In her book, Carrington draws and describes a world of infinite possibilities for the imagination. Alemani, an Italian living in New York, and director and chief curator of High Line Art since 2011, was tapped to organize the main thematic exhibition at the 2022 Venice Biennale. She made the judicious choice of adopting a historicist approach that highlights the crucial role played by women artists during the twentieth century within, among others, the Surrealist movement, and their contributions to reflections challenging the dividing lines among humans, animals, and new technologies. In addition, Alemani brought a breath of fresh air to this major event inaugurated in 1895 by assigning the majority of places to women and nonbinary artists. A total of 213 creators from 58 countries were invited to present their work in Venice.

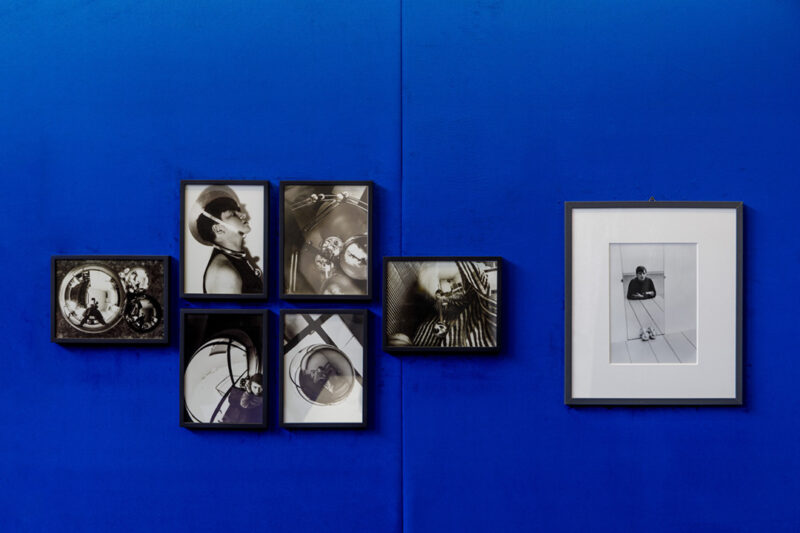

Displayed in the Giardini main pavilion and at the Arsenal, the exhibition The Milk of Dreams presents, in alternation, five “time capsules” (Alemani’s term) and contemporary works. The former anchor the premise of the thematic exhibition and invite viewers to make parallels between past and present. One of the capsules, titled after a short film by Maya Deren, The Witch’s Cradle (1943), brings together works by artists who have refuted the idea that humans are at the centre of the universe and that everything is measured against them. Among the works on display, photographs by Claude Cahun and Florence Henri reveal the ambiguity of the representation of genders – a topic that is also explored in works by a number of contemporary artists, including Polish photographer Aneta Grzeskykowska. In her series Mama, Grzeskykowska reverses the roles of mother and daughter: it is the daughter who gives her mother a bath or pushes her in a pram along a river bank. Amplifying the surreal atmosphere is that the daughter is human and the mother is a mannequin.

Another time capsule, Seduction of the Cyborg, features works by Marianne Brandt, Alexandra Exter, Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, Hannah Höch, and Anu Põder, among others. This capsule provides an eloquent glimpse at the way in which these twentieth-century artists explored, transgressed, or contested the divisions between humans, animals, and new technologies. In the adjacent contemporary section, several artists emphasize how much these lines are continually being pushed back. For example, the video Paralyzes the Heart, by the American artist Lynn Hershman Leeson, features a sixty-one-year-old female cyborg discussing military control and surveillance systems. This poignant work offers an articulate critique of artificial intelligence. The Polish photographer Joanna Piotrowska delves, sometimes playfully and evocatively, into the hierarchies of power in daily life and the so-called security that we might feel at home. As part of her series Frantic (2016–19), Piotrowska invited people to build shelters in their dwellings. The resulting images expose how inadequate the physical environment is in protecting us from everything; it can’t keep physical or verbal violence away.

Many works shown in the biennale are notable for being hybrid or surrealistic. This is the case for the stunning coloured-crystal sculptures by the Romanian artist Andra Ursuta and the fantastical drawings by the Inuit artist Shuvinai Ashoona. Opening the exhibition path at the Arsenal, Simone Leigh’s Brick House is impressively large, but an attentive examination reveals that the work is half-house, half-woman. The lower part of the sculpture was inspired by various architectural types, including mud huts (tòlék) built by the Musgum people, while the upper part presents a woman’s head, eyeless but adorned with braids. Brick House evokes courage and resiliency even as it pays tribute to women of the African diaspora. Farther on, the five oven-shaped terracotta sculptures by the Argentine artist Gabriel Chaile form portraits of her ancestors from descriptions transmitted by oral tradition. The result is startling and striking: it offers an alternative to portraiture based on individuals’ physical attributes.

Many artists draw on nature as their primary inspiration. In the spirit of Walter de Maria’s New York Earth Room (1977), the Colombian artist Delcy Morelos invites visitors to enter the labyrinth that she has built with natural materials – earth, clay, cinnamon, cacao, and tobacco – that stimulate the olfactory sense and offer respite to anyone who takes the time to stroll through the paths with walls a metre and a half high. A little distance away, visitors can experience a huge garden of swiftly growing kudzu, To See the Earth Before the End of the World. In choosing this Asian climbing vine, the Nigerian-American artist Previous Okoyomon harkened back to 1876, when it was introduced to Mississippi farms to counter the erosion of soil that had been destabilized by monoculture cotton cultivation. The work is a salient metaphor for the intertwining of elements such as enslavement, diaspora, and nature – the last of which always wins in the end. The Lebanese artist Ali Cherri, in her three-channel video installation Of Men and Gods and Mud, explores the ecological and human repercussions of one of the largest hydroelectric dams in Africa: the Merowe dam on the Nile, in northern Sudan. During the day, bricklayers go about their arduous tasks; at night, a man makes a monster out of earth; the monster alludes to the impact of the forced displacement of fifty thousand people when the dam was built more than twenty years ago.

Despite the obstacles encountered by Alemani and her team – the inability to travel during the pandemic and the one-year delay in holding the event – the 2022 Venice Biennale is a rich, stimulating edition bringing visitors face to face with complex works that invite them to take a closer look – but not confrontationally – at a variety of current events, including climate change, racism, decolonialization, and imperialism. In videos, photographs, paintings, drawings, woven pieces, installations, performances, and sculptures, the artists address one or more of these subjects in a considered, creative, subtle, and disciplined way. Their works take visitors from one world to another, one dream to another, one nightmare to another. Ultimately, the fruits of the artists’ labour – the milk of their dreams – shows that when imagination is used to rethink the world, the possibilities are endless.

Ariane Noël de Tilly is a professor in the Department of Art History at the Savannah College of Art and Design. She holds a PhD in art history from the University of Amsterdam and has completed postdoctoral studies at the University of British Columbia. In her research, she examines the exhibition and preservation of contemporary art, the history of exhibitions, and engaged art.