[October 26, 2022]

By Ray Cronin

The portrait-photograph, Roland Barthes wrote, is a “closed field,” the intersection of four forces or “image-repertoires”: “The [person] I think I am, the one I want others to think I am, the one the photographer thinks I am, and the one he makes use of to exhibit his art.”1 But doesn’t Barthes’s closed field hold only from the perspective of the person being photographed? For the viewer, far from being closed, the photograph is open – open to our interpretation, to our individual readings. And that’s because, again following Barthes, there is a fifth image-repertoire: the physical object that represents a person without being one. We never really think that we are standing face to face with another being when we look at a portrait photograph; we always know that we are dealing with a document. It is the play of these four forces that Barthes says “oppose” and “distort” each other, seen from the perspective of this fifth image-repertoire, that makes the portrait photograph so compelling. This play makes us want to keep looking.

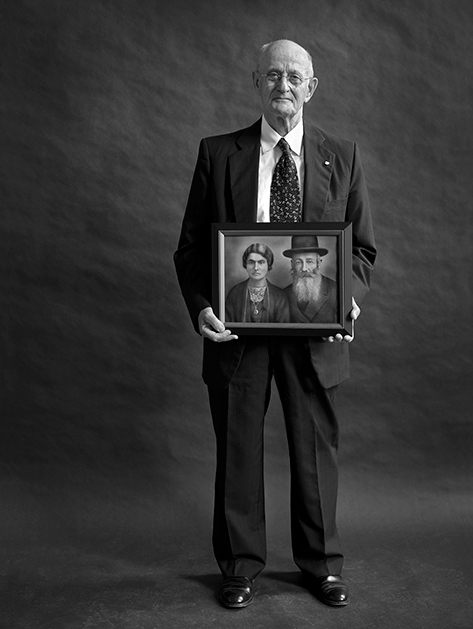

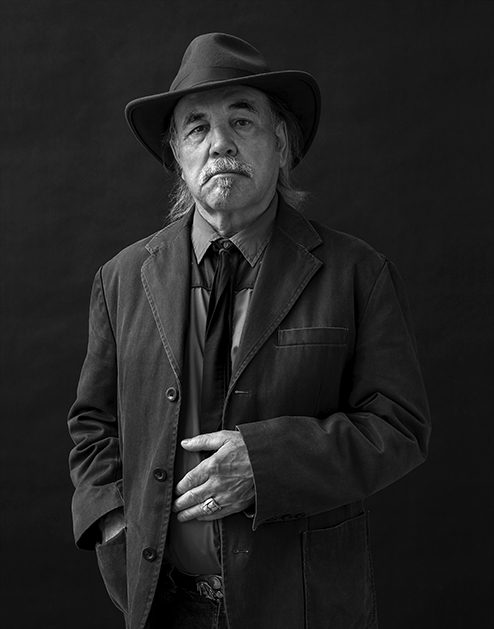

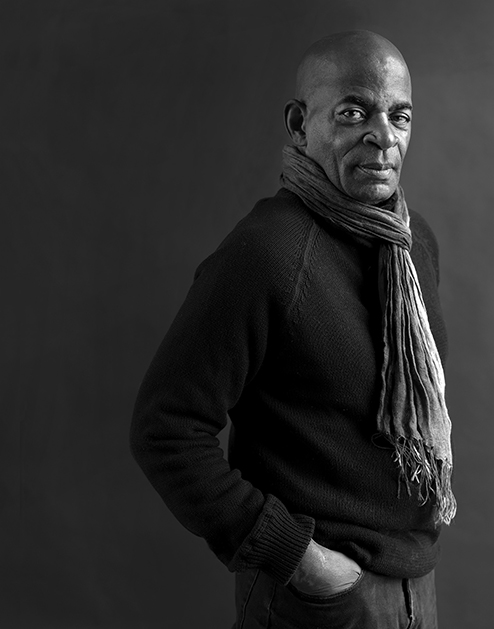

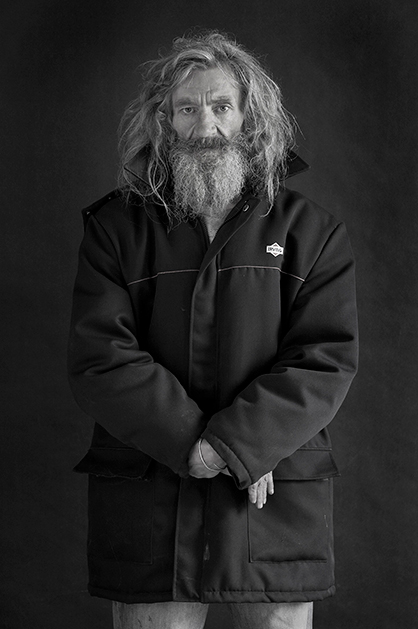

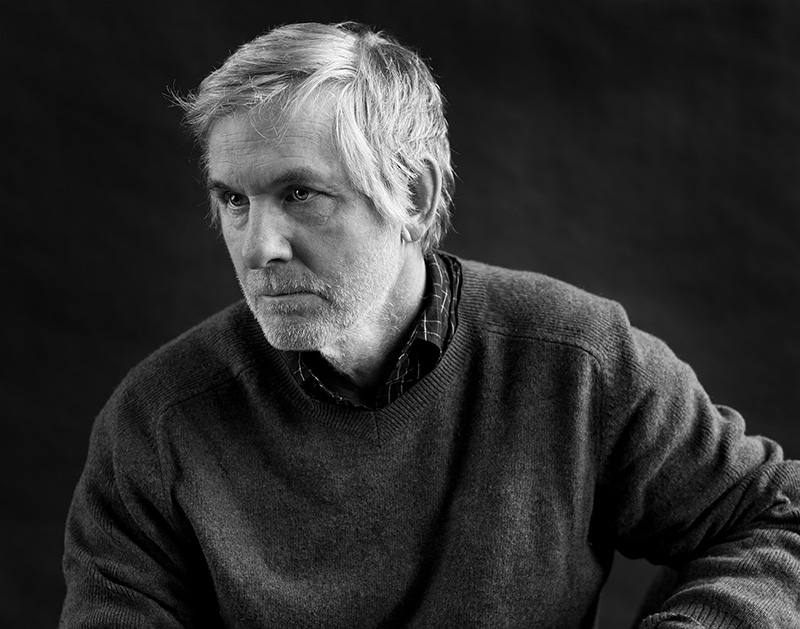

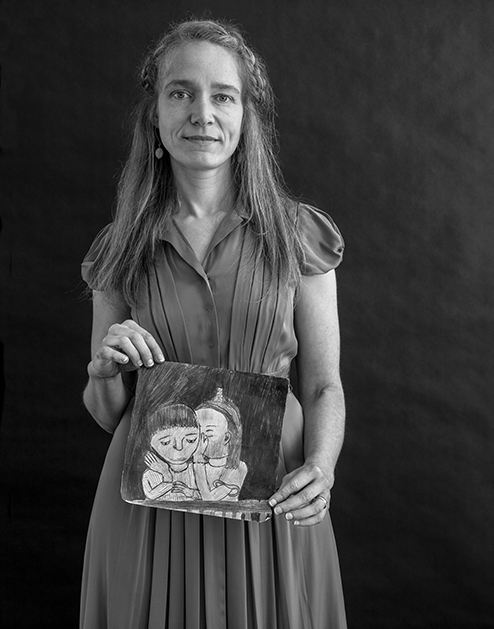

Social Studies, James Wilson’s series of large photographs, depicts people from all walks of life in his native New Brunswick. The portraits all share the same format: half, three-quarter, or full-length black-and-white images of people posed against a neutral grey background, illuminated only with natural light. Wilson has been working on the series from which the images in Social Studies are drawn for twenty-five years. The earliest works were photographed with a view camera, the later works (post-2011) digitally. On exhibit at Fredericton’s Beaverbrook Art Gallery,2 the photographs are also gathered into a book.3 Both formats bring spectators (whether viewers or readers) the unique pleasure of the photographic portrait. In the gallery, the works take on a certain presence due, in part, to their large format. The individuals depicted (and they are almost all individuals) take on a certain gravitas hanging in the gallery space. So do we. However lost we may become in the works on display, there is always an element of ourselves being on exhibit – playing the role of audience in a bit of social theatre. Our posing in front of them mirrors the poses the subjects adopted in front of the photographer. Barthes knew this weird doubling: “I constitute myself in the process of ‘posing,’ I instantaneously… transform myself in advance into an image.”4

Wilson takes full advantage of this transformation, asking his subjects to pose in ways that reflect their roles, that display themselves as characters. In some cases, this is a literal process: Betsy Grannan presents herself in the guise of “Jayne Maneater,” a roller derby competitor. Marshall Button, an actor, takes on the role of “Lucien,” his garrulous blue-collar alter ego. And Larry Merritt, a self-described “right-wing conservative,” displays himself in a clichéd version of that label: wearing a sleeveless t-shirt, his hand on a revolver stuck in his waistband. In others, the roles presented are more formal: Valéry Vienneau in the gorgeous robes of an archbishop; Kris Evong in the camouflage smock, uniform, and face-obscuring headdress of a Canadian Forces sniper; Nawal Doucette in the costume she wears while performing as a belly dancer. Still others are more subtle in their roles; David Adams Richards, a novelist, stares off out of the picture frame, following his imagination perhaps, leaving his portrait behind. Katherine Mary Savage, a nun and teacher, also stares to the side, her face bathed in a shaft of sunlight from a window out of the frame. Wilson recounts in the book that Savage had recently suffered a stroke and was having a difficult time focusing on the camera. Turning her toward the fortuitous light created an image suggestive of revelation. Romantic? Certainly.

That’s one of the pitfalls of portrait photographs: our drive to read into them. “The camera is a time machine,” says Wilson, fixing “one frozen moment.”5 A documentary photograph fixes a moment in time in front of us. For a moment, the photograph freezes us as well, as we travel back in time. As Wilson so obviously understands, when a photograph speaks to us, it is always in the past tense.

2 James Wilson: Social Studies was held between July 29, 2022 and November 6, 2022.

3 James Wilson, Social Studies (Fredericton and Saint John: Goose Lane Editions and James Wilson Photography, 2020).

4 Barthes, Camera Lucida, 10.

5 James Wilson, Social Studies, 11.

James Wilson has been an artist working in the medium of photography for more than forty years. Wilson works from his home and natural light studio near Hampton, New Brunswick. He uses large-format cameras mostly, making images of the land or documenting people in great detail. He has exhibited in numerous individual and group shows, both internationally and throughout Canada. His photographs have been acquired by public collections, including by the National Gallery of Canada, and by corporate and private collections around the world.

Ray Cronin is a Nova Scotia–based writer, curator, and editor. He is the author of eleven books on Canadian art, including the ongoing Gaspereau Field Guides to Canadian Artists series. He is editor-in-chief of Billie: Visual Culture Atlantic, regularly contributes to Canadian and American magazines, and frequently writes for gallery exhibition catalogues. He is the founding curator of the Sobey Art Award and the former director and CEO of the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia.