[Winter 2011]

by Mona Hakim

Mona Hakim: Your recent photographic project is called Histoires [Stories]. What do these fragments of accounts relate to us ?

Alain Pratte: The images in Histoires narrate a trip – a trip made of a thousand movements through a familiar place: Montreal. It’s a trip that also takes place in the head, what you could call an inner trip – that is, it’s the result of a state of mind, hypotheses, bursts of curiosity, critical tensions …

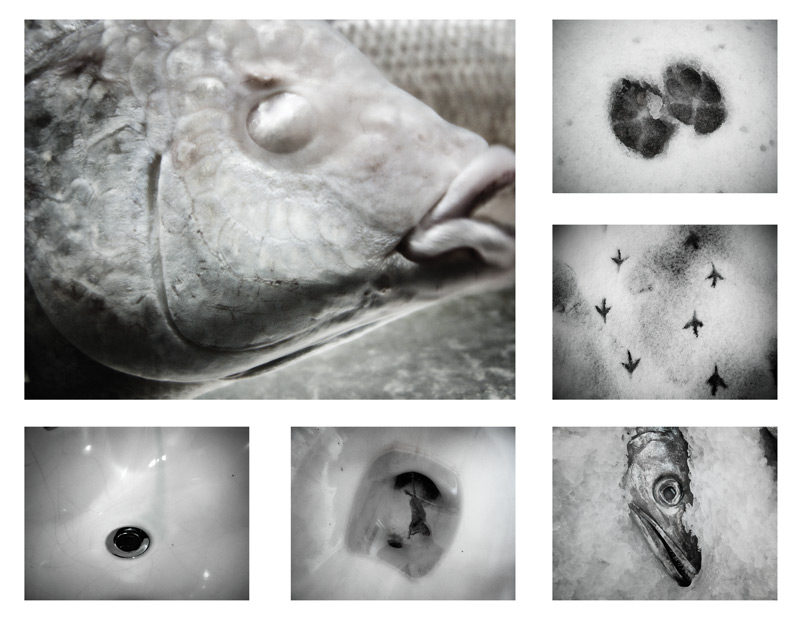

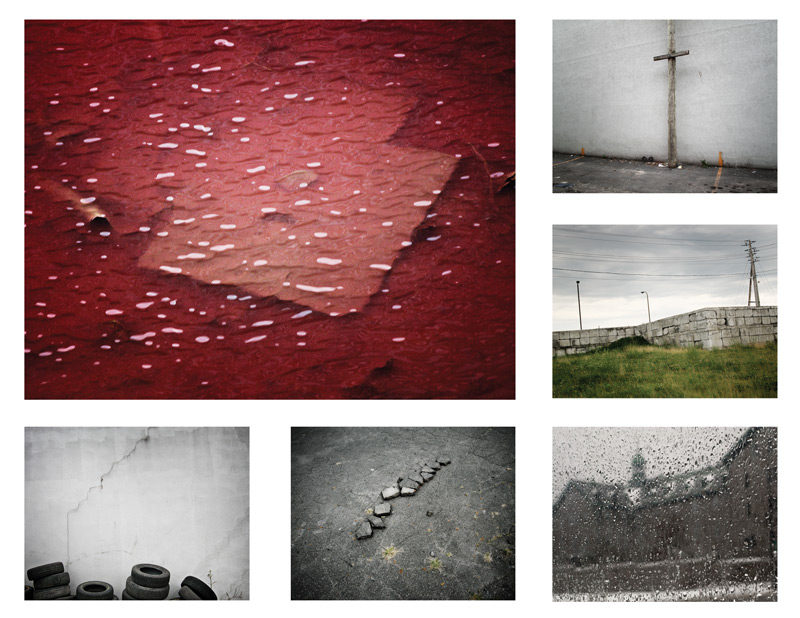

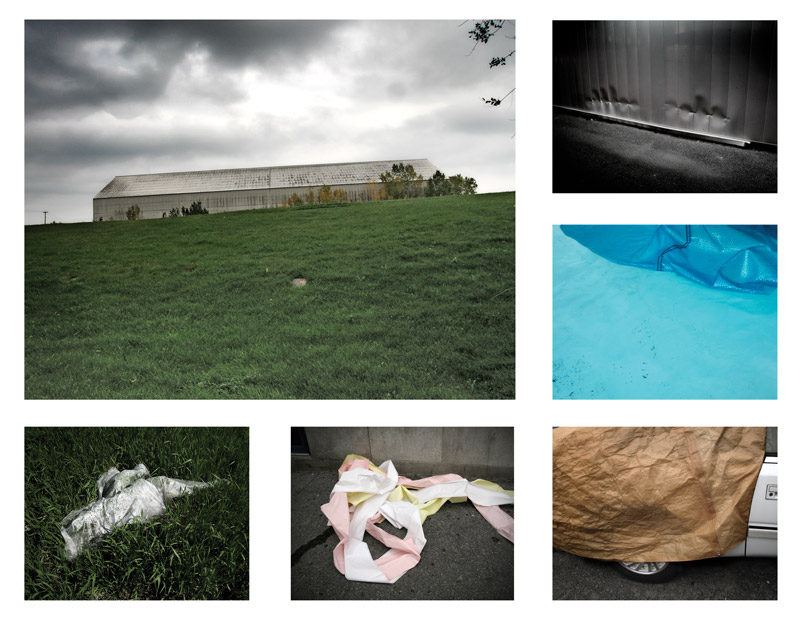

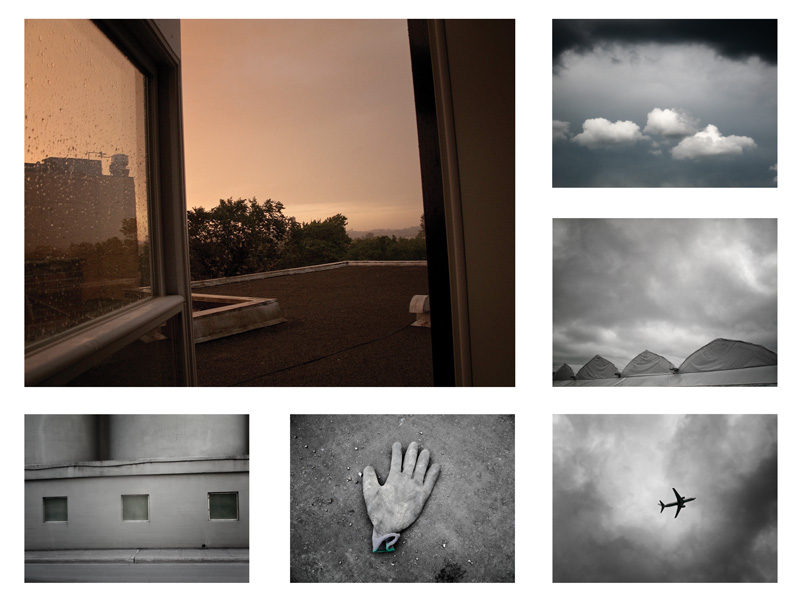

The project is called Histoires because everything carries within itself the weight of narrative, and the arrangement and selection of images produces a new geographic and mental space that refers to known places, but that in the end is just an invention, a mise en scène. The images in the series show places, things, particular situations, decontextualized then recontextualized, inserted into a context that is ultimately pure invention.

MH: The notion of mystery, or even intrigue, has always been more or less present in your previous projects. Isn’t it more accentuated here ?

AP: Histoires bears a slight resemblance to film noir of the 1940s and 1950s: ambiences, locations, and sets in which actions are possible, mysteries are pondered, tragedies may occur, intrigues may take shape. Everything is latent, merely suggested. In that sense, this series is built in the spirit of À rebours, a video that I made in 2003 using found negatives. The Histoires series also shows chunks of reality. Each image of this reality belongs, however, to a threefold universe: that of the real, that of perception, and that of a construction that I propose. Caught up in a series of tiny shocks, viewers are confronted with a world that is both familiar and elusive. Images that appear innocuous may take on dramatic or unusual dimensions simply because mystery surrounds them. Photographs of objects, places, traces, people, or animals make the eye wander through a space both fictional and documentary that recalls, in certain ways, the travel account, an adventure novel, or winding trails.

MH: What connection do you make between how narrative contributes to your work and your vision of photography in general ?

AP: Photography may be many things. I’ve always thought that it is a problematic medium: it is so simplistic that it has ended up seeming very complicated to me. Photography never accounts for all of reality; it allows for elements to be isolated and magnified. From there, we have the choice of making documentary or decorative images, or both at the same time. We can also create fictional situations and photograph them, but in my view this is no longer photography but photographed theatre.

A group of juxtaposed images showing me slices of reality and nothing else generally leaves me wanting. It’s true that the medium is a bit handicapped, a bit deficient compared to film or literature. This is no doubt why so many photographers opt for an approach that aestheticizes the image. The important thing, then, is not to seek what is lacking in photography but to exploit its uniqueness – its capacity to produce fixed images that may become notable or memorable if certain conditions are brought together.

What interests me is to see how an image or group of images assembled in a certain order and in a certain way might resonate.

Unlike film, photography allows the passing of time to be stopped and different moments of life to be shown simultaneously. It therefore allows for a temporal mise en scène of the world. We could think of a sequence of two images showing a before and an after. When these two moments of an object, a being, or a place are shown, the entire temporal space between the two instants is evoked. Even in this very simple construction, a narrative form is organized.

Photographers who work in series apply, more or less consciously, this idea of a dialogue between images. This dialogue is often summarized in aesthetic affinities or a unity of subject. But my premise is the following: an image that has meaning in a certain context may be taken away from this context and inserted into another that it will enhance or not, depending on its particular qualities.

When I visit a photography exhibition, my purpose isn’t to look at images, understand their meaning, and appreciate their aesthetic qualities; rather, I want to understand the particular space to which these images as a whole take me. If, on the whole, all they do is bring me back to the reality that they represent, I feel that the narrative line is either deficient or absent. We are too bombarded with images of reality for this contribution alone to be of interest other than for observation – observation reinforced by redundancy. The contribution of narrative allows for an escape from boring tautologies.

MH: In some ways, serial photography, through a play on associations, maintains links with the psychic dynamic. This fact may respond to the “particular space” that you mention. What importance do you place on the notion of the unconscious or the memory work ?

AP: The conscious, the unconscious – these are notions that don’t really concern me. My approach is not meant to be introspective. Generally, this type of self-examination bores me a little. What interests me is to see how an image or group of images assembled in a certain order and in a certain way might resonate. What has resonance for me may not for someone else. It’s a wager to be made. And since this “particular space” is shaped as it is constructed, a moment comes when I no longer know whether the space itself imposes its images or whether I, the photographer, imposes them on the anticipated space. I have one way of looking at what’s around me. In the end, that is what I offer. Everything that is portrayed will find a reflection in the memory of the person looking at it.

MH: What is your working method ?

AP: My work involves a number of successive or simultaneous steps, from taking the picture to forming the corpus. But when one considers the picture-taking aspect only, the method is relatively simple. First, I should mention that each project requires a certain formal framework, and that once this framework is established, the visible reality is read differently. Each project also requires a state of mind that is enhanced by reading, discussion, and wandering.

My method ? To take every opportunity to find images that will enhance the corpus, inject energy, inflect it. A day without producing images is a lost day, I would almost say. So, I look for images every day. It’s a little like going fishing, like leaving on an expedition. Sometimes I want to find them and I don’t; I go home empty-handed. Other times, I find things I couldn’t have hoped to find, things I hadn’t yet imagined.

Establishing the corpus is a delicate step, of course. I spread out my photographs and I try to let myself be guided by what is woven among them. Sometimes there is humour; sometimes, bitterness; often, irony. My series have to be strong enough that a story can infiltrate them, and flexible enough that several stories can cross paths.

MH: You mention the need for having a formal framework before undertaking your project. And so I must mention the formal structure of your last project, built very methodically, even with great discipline: identical groupings of images (same number, same format), formal relationship between certain iconographic motifs, and so on. As a successor to your wanderings, what is this formal logic based on ?

AP: I believe that images find legibility in a certain formal unity, and also in restraint. Here, the images are simple, and that gives them instant legibility. Images that are too crowded would only impede the formal interactions and block the possibilities for reading them. In a group of images, an internal logic must be imposed – a logic that combines both “aesthetic” and meaningful elements.

The forms often evoke realities that have nothing to do with the objects photographed. The objects themselves, in their plainly prosaic nature, often refer to things that have nothing to do with their primary meaning. It is these superimposed portrayals that are brought forth in the images and that make them equivocal. And this ambiguity at the core of the project constitutes its main interest. Without a formal constitutive logic, this project would not function.

As for the groupings, the geometric wager aims to offer a framework for reading at a regular pace. Disparate formats would give an impression of confusion rather than thoughtful construction. Also, having a large image flanked by smaller ones allows for a serial reading of the plates; the big images dominate and, at the same time, push the small ones to the background; it is then understood that they are the backbone of a larger ensemble.

Translated by Käthe Roth

Since 1973, Alain Pratte has produced numerous photographic projects, a number of which have been in exhibitions in Canada and abroad, including France and Venezuela. His work bears witness to passing time, the permanence or fleeting aspect of objects, unpredictable fates, and illusory ambitions. Pratte also works in cinema, among other things as a writer and screenplay consultant. He lives and works in Montreal.

Mona Hakim is a curator, historian, and art critic. She has written a number of articles, monographs on artists, and catalogue texts, and she has a predilection for photography. She teaches history of art and photography at CEGEP André-Laurendeau in Montreal.