[Winter 2013]

Standard Operating Procedure, directed by Errol Morris, offers a concise example of a methodological shift – what we (in the European Research Council project that I am affiliated with) have elsewhere called a forensic turn – within the investigation of human rights violations and war crimes.1 The film examines the central role of photography in registering the torture and abuse of Iraqi detainees at Abu Ghraib prison (2004) as both a technical practice out of which discrete image-objects emerged – the scandalous photos of the hooded man and naked human pyramid – and a social technology that produced a series of image-events, which brought U.S.military actors, Iraqi prisoners, and digital technologies into new political configurations organized by various forms of coercive power.

by Susan Schuppli

Standard Operating Procedure is structured by a series of interlaced sequences that draw out the tension between two primary forms of witnessing: the human and the machinic. The first features as a form of direct address to the filmmaker’s camera. These sequences consist of U.S. Army personnel, many of whom participated in (and were later charged with) acts of prisoner abuse, reflecting upon the incidents at Abu Ghraib. The second mode of witnessing is performed by the operations of the camera itself. These technical witness account (the ensuing digital archive) were largely regarded as direct evidence of deviant criminality among a handful of low-level “bad apples.” The human subject who, through his or her own – in the case of Abu Ghraib, compromised – experience is able to narrate a sequence of events as an eye-witness is juxtaposed throughout the film against the mimetic regime of the technical object – the photograph – whose capacity for absolute recall seems to dispel the necessity for a human interlocutor to explicate its content. This friction between forms of historical proof within the film signals a paradigm shift between the human witness and the material witness that is fast becoming the hallmark of an emergent forensic sensibility.

The primacy previously accorded to the human witness and to the subjective and linguistic dimensions of testimony, in particular as it concerned post-war trauma, has had such an enormous cultural, aesthetic, and political impact that it prompted literary critic Shoshana Felman to characterize the twentieth century as an “era of testimony.”2 However, this primacy is gradually being supplemented by a forensic – which is to say, an increasingly techno-scientific – account of history, one that has shifted the emphasis toward an object-oriented juridical culture immersed in matter and code and away from the affective realm of human experience and first-person testimonial. The presentation of scientific evidence by experts, exemplified by the “truth-telling” status of the DNA test, has moved beyond the juridical sphere to make its presence felt in the expanded fields of politics and aesthetics.3 This is a shift in cultural receptivity that Standard Operating Procedure negotiates as its structuring polemic.

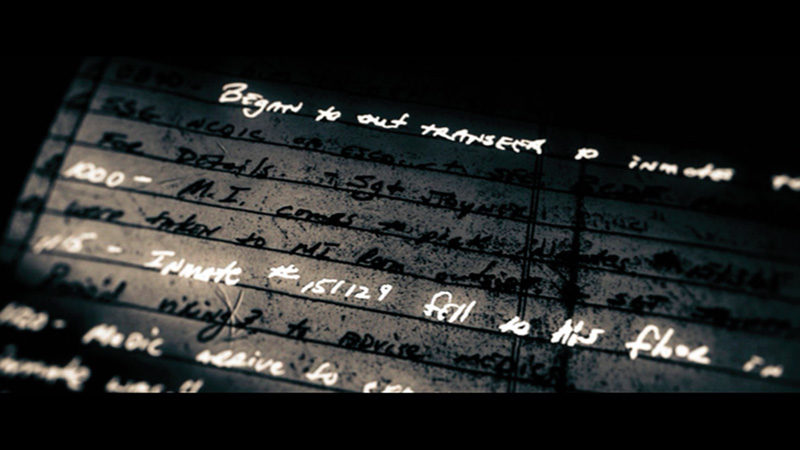

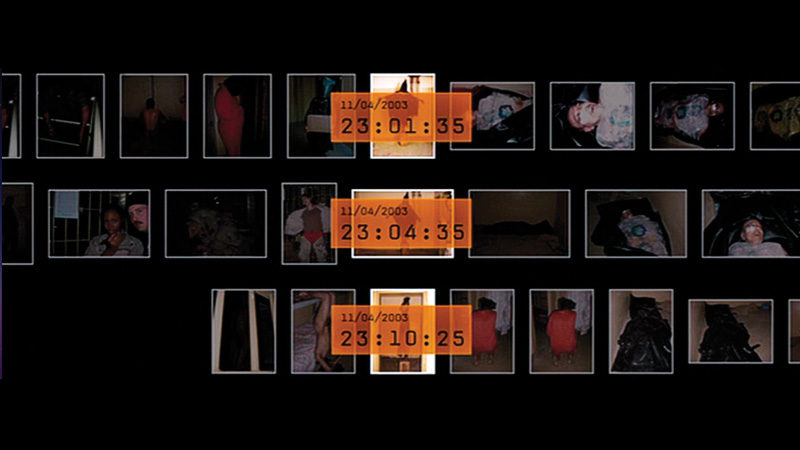

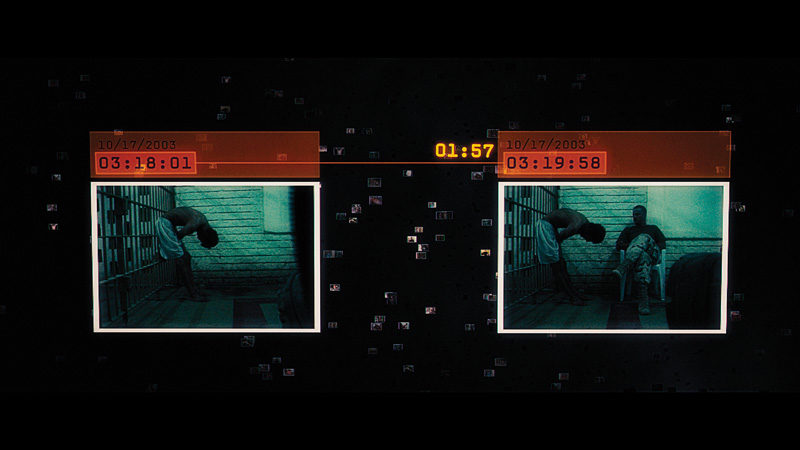

A pivotal scene occurs early in the documentary, when Brent Pack, Army Special Agent in the Criminal Investigation Division, takes us through the laborious process of correcting time-codes for the thousands of images taken at Abu Ghraib in order to generate a time-line of events that can be synced with the prison logbooks. He does this by examining the metadata of each image, which, in spite of being repeatedly copied and burned to CD, remained intact. By matching similar frames across multiple cameras shooting at different resolutions, each of which registered a different date and time stamp, he is able to produce a media archaeology that locates victims and perpetrators within the various temporal strata of Abu Ghraib. Reorganizing this massive image-dump into a legible sequence of events was crucial in constructing the legal file for the jury. The forensic analysis of metadata encoded in each image file thus transformed seemingly random acts of aberrant behaviour into systematic and repeated practices of prisoner abuse.

The presentation of scientific evidence by experts, exemplified by the “truth-telling” status of the DNA test, has moved beyond the juridical sphere to make its presence felt in the expanded fields of politics and aesthetics.3 This is a shift in cultural receptivity that Standard Operating Procedure negotiates as its structuring polemic.

“The pictures spoke a thousand words but unless you know what day and time they were talking [about] you wouldn’t know what the story was. I started lining pictures up based on subject matter. Put these on a timeline so the jury could see when did the incident begin, when did it end, how much time elapsed in between these photographs. How much actual effort did these people put into what they were doing to the prisoners. Who else was there in the room at the time it occurred. How could all this go on without anybody noticing it?”4

Forensics, if traced back to its etymological origins in Latin – forensis – refers to the proficiency and rhetorical competency in the presentation of evidence before a forum such as the gathering of a public in a court. Forensic science, by contrast, although defined as a “science in service to the courts,” emphasizes inscriptive processes, whereby minute details can be technically conjured from within the material substrates of trace-evidence, rather than elocutionary ones. Whether such forensic evidence is directed toward the resolution of a dispute over the meaning of things or clarifying a chain of events in relation to an accident or a crime, the entry of evidentiary matter into the juridical process as a material witness is still determined by a series of negotiations around what claims can actually be made in its name. Evidence is less about the truth-telling status of an object than about its semantic capacities as defined by the institutions in which public witnessing can take place. Errol Morris, in both this film and his recently published book Believing is Seeing: Observations on the Mysteries of Photography, argues likewise that what we see in an image is ultimately governed by what we believe to be true rather than any epistemological certainty. He uses the example of Sabrina Harman’s thumbs-up gesture and smile as she poses over the dead body of Manadel al-Jamadi, an act that sealed her legal fate as guilty of prisoner abuse.

Morris argues that Harman’s amoral expression of pleasure is in fact a rote response to being photographed, and, indeed, further examination of pictures in which she appears always depict the same thumbs-up pose regardless of context. In fact, says Morris, what Harman is actually doing is providing important documentary evidence of criminal behaviour by u.s. Military Intelligence (MI), whose interrogative methods resulted in al-Jamadi’s death. Rather than immediately convert the image into a ghoulish indictment of her character, we ought to see it for what it is – witness to a brutal homicide by MI that otherwise would have gone unreported. By focusing on Harman’s deviance, we don’t see what is really at stake in the image. Forensics is ultimately a mode of negotiation whereby objects become the agents of translation between differing versions of events or contestations between stakeholders. The ability of an artefact to speak its embedded histories is not simply a question of the kinds of scientific advances that can be brought to bear upon things, but is a consequence of the conditions that govern the limits of what may be thought and spoken at any given time. Morris complicates the witness regimes operative at Abu Ghraib in suggesting that acts performed expressly for the camera were, in certain instances, misread because of the pre-emptive narratives brought to bear upon them. Their capacity to testify to the real horrors of Abu Ghraib, which might have implicated the entire u.s. chain of command, was diverted to indicting minor players. He makes this argument by turning his own camera back onto the protagonists so that they might enlarge the frame of understanding. It is at this crossroads between the burden of proof carried by the image – its probative value as direct legal evidence – and the image burdened by the search for an explicative proof – the need to account for the events pictured – that I would locate the forensic turn in Standard Operating Procedure.

2 See Shoshana Felman, The Juridical Unconscious: Trials and Traumas in the Twentieth Century (London: Harvard University Press, 2002). See also Eyal Weizman on forensic aesthetics, a term that was separately explored by Thomas Keenan, Hito Steyerl, and Eyal Weizman in the exhibition “Mengele’s Skull: The Advent of Forensic Aesthetics” at the Portikus gallery Frankfurt in 2012. staedelschule.de/forensic_aesthetics_d.html.

3 These ideas draw on a text written jointly by Eyal Weizman and me for a grant.

4 Brent Pack, Army Special Agent in the Criminal Investigation Division, speaking in the film Standard Operating Procedure, dir. Errol Morris, Sony Pictures Classics, 2008.

Errol Morris is a writer and filmmaker. His movie The Fog of War: Eleven Lessons From the Life of Robert S. McNamara won the Academy Award for best documentary feature in 2004. Gates of Heaven, his first film, has for many years been on Roger Ebert’s list of the ten best movies ever made. The Thin Blue Line helped to establish Morris as one of the leading figures in American documentary film making, and pioneered the use of re-creations in documentaries in film and on television. Believing is Seeing: Observations on the Mysteries of Photography, a book of his essays, is a New York Times best seller. Morris’s new film, Tabloid, the story of Joyce McKinney, the “manacled Mormon,” and her five pit-bull clones, is on DVD. His book, A Wilderness of Error: The Trials of Jeffrey MacDonald, was published in September 2012. He is a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and lives in Cambridge, Massachusetts. errolmorris.com

Susan Schuppli is a media artist and cultural theorist who is a Senior Research Fellow in Forensic Architecture at Goldsmiths University of London, where she also received her doctorate. Previously, she participated in the Whitney Independent Study Program and completed her MFA at the University of California San Diego. Her research on the “material as witness” is the subject of a documentary film and book project.