[Winter 2013]

By Vincent Lavoie

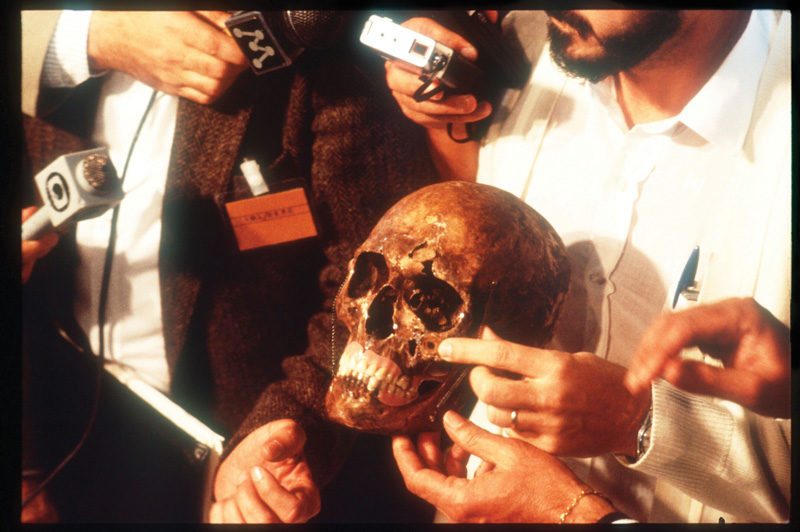

On 6 June 1985, the international press was invited to the small Embu das Artes cemetery in Brazil to witness an extraordinary discovery. A team of police officers and medico-legal experts had just exhumed the presumed remains of Josef Mengele, the Nazi doctor at Auschwitz. A series of photographs taken on this occasion by reporter Robert Nickelsberg show the press’s infatuation with this event, which, beyond its historical dimension, conferred upon forensics an unprecedented probative power. As Thomas Keenan and Eyal Weizman explain, “The Mengele investigation opened up what can now be seen as a third narrative in war crime investigations – not that of the document or the witness but rather the birth of forensic approach to understanding war crimes and crimes against humanity.” The current cultural prestige of forensics is due, in part, to the media coverage of this exhumation, which established the figure of the expert by showing him making deictic gestures, dwelling on the details of the skeleton, holding forth on the distinctive marks on the specimen. A few years later, the spectacularization of forensics was sanctified during the O. J. Simpson trial, which was broadcast on television. Whether through the debates surrounding the contamination of DNA evidence or the theatrical trying on of a blood-stained black glove, the interminable lawyers’ speeches and the blunt performances of the witnesses relegated the visual evidence to a supporting role in the establishment of truth. In fact, at the time the historically acknowledged power of persuasion of media images was undergoing a devaluation. The introduction of computerized tools into the editorial process was raising doubts about the credibility of visual journalism, and its code of ethics had to be reviewed in light of this technological evolution. On 6 June 1985, the international press was invited to the small Embu das Artes cemetery in Brazil to witness an extraordinary discovery.

Contemporary cultural representations, whether televised or literary, are focused particularly on the scientific aspect of forensics, notably investigation and analysis protocols, which are described at a rare level of detail.

A team of police officers and medico-legal experts had just exhumed the presumed remains of Josef Mengele, the Nazi doctor at Auschwitz. A series of photographs taken on this occasion by reporter Robert Nickelsberg show the press’s infatuation with this event, which, beyond its historical dimension, conferred upon forensics an unprecedented probative power. As Thomas Keenan and Eyal Weizman explain, “The Mengele investigation opened up what can now be seen as a third narrative in war crime investigations – not that of the document or the witness but rather the birth of forensic approach to understanding war crimes and crimes against humanity.”1 The current cultural prestige of forensics is due, in part, to the media coverage of this exhumation, which established the figure of the expert by showing him making deictic gestures, dwelling on the details of the skeleton, holding forth on the distinctive marks on the specimen. A few years later, the spectacularization of forensics was sanctified during the O. J. Simpson trial, which was broadcast on television. Whether through the debates surrounding the contamination of dna evidence or the theatrical trying on of a blood-stained black glove, the interminable lawyers’ speeches and the blunt performances of the witnesses relegated the visual evidence to a supporting role in the establishment of truth. In fact, at the time the historically acknowledged power of persuasion of media images was undergoing a devaluation. The introduction of computerized tools into the editorial process was raising doubts about the credibility of visual journalism, and its code of ethics had to be reviewed in light of this technological evolution.2 The admissibility of digital photographs as evidence posed a similar problem. Because they could be manipulated, their legal value was undermined in the view of a number of observers.3

The image is no longer the seat of absolute belief; the truth is now lodged in the infravisible universe of fibres, body fluids, molecules, and other indicial evidence uncovered in police technical and scientific laboratories. And yet, is the fate of the image sealed? Given the apparent irrefutability of scientific evidence, what status can be claimed for visual representation? Is the impeachment of the image as purveyor of truths irrevocable? The art practices brought together in this issue reopen the case on the image, looking at the facts and making an argument for a recasting of the visibilities of legal evidence. Like a legal argument, these works persuade us of the need to challenge this spectacularization of forensics, which summons up a group of considerations that we might have thought forever discredited by postmodern critique : evidence, authenticity, testimony – all notions that make us sniff out the suspect return of discourses of truth.

From Genre to CSI Syndrome. Contemporary cultural representations, whether televised or literary, are focused particularly on the scientific aspect of forensics, notably investigation and analysis protocols, which are described at a rare level of detail. This reality is observable in current literature – for instance, the novels by Kathy Reichs (Déjà Dead, 1997), herself a forensic anthropologist by profession, Patricia Cornwell (Body of Evidence, 1991), Ridley Pearson (The Chain of Evidence, 1995), and Thomas T. Noguchi and Arthur Lyons (Physical Evidence, 1991), all bestsellers featuring the exploits of the new figure of legal probity: the forensics expert. As the very titles of these novels reveal, the search for evidence, especially the most subtle (fibres, fluids, fingerprints), underlies the plots of these stories, many of which are inspired by real situations. A number of very popular television series (Crime Scene Investigation, premièred 2000; Forensic Files, premièred 2000) also convey a belief in the infallibility of medico-legal expertise. In these programs, scientific rationality is offered as the absolute antidote to doubt. They prominently feature experts who dispense brilliant demonstrations of pedagogy-tinged justifications and explanations. In addition to standing in for objective knowledge, the experts’ demonstrations appear, to some, a form of teaching worthy of trust. Their rhetoric tends invariably to prove the irrefutability of the conclusions. A number of jurists are now challenging the possible impact of these television programs on the functioning of justice. Some see in the media over-coverage of scientific evidence a devaluation of “circumstantial” evidence in the courtroom.4 Rhetoric, the cornerstone of legal argument, seems to give way to the implacable testimonial power of scientific evidence. In effect, it has been observed that during trials, juries are more inclined to convict or acquit defendants if scientific evidence of their guilt or innocence is presented. More and more, the parties involved in trials demand that evidence presented in court be verified by experts. Lawyers complain that juries acquit defendants in the absence of any scientific evidence. These are the effects of “csi syndrome,” a form of social ailment about which much has been written in recent years.5

“Forensic.” Our affinity for evidentiary systems that purvey incontestable truths has as an emblem the word forensic.6 Disciplines engaged in criminal inquiries are now tagged with this term: forensic anthropology, forensic linguistics, forensic entomology, forensic botany, and so on. The addition of this qualifier is revealing of the turn to forensics that these sciences and disciplines have taken in recent decades. For instance, forensic anthropology, to take an example popularized by the television series Bones (premièred 2005), refers to the legal applications of this discipline in the human sciences. Using the methods of biological anthropology, forensic anthropologists seek to determine, by studying human bones, the identity, sex, size, and ethnic origin of a subject. They see bones as a sort of text that they are expected to interpret. Anthropologist Clyde Snow summed it up perfectly, when he was asked to identify the bones of war criminal Josef Mengele, who died in Brazil in 1979, by saying, “Bones make great witnesses, they speak softly but they never forget and they never lie.”7

Forensic linguistics involves the analysis of speech acts (interrogations, testimonies) to find signs of plagiarism and authenticate writings. A linguist invited to give an opinion in a legal context will usually be mandated to assess written or oral statements using discursive analytic clues of various types (phonetic, semantic, and so on).8 Determining the time or date of a death through the examination of larvae and insects found near or on the cadaver is the role of the forensic entomologist. A toxicological analysis of the biological composition of larvae may, in addition, reveal traces of poison or drugs. It is up to the forensic botanist to identify spores discovered on a victim’s body or clothing and ascertain their provenance in relation to the site where the body is discovered. As we can see from these few examples, the forensic applications of biological and human sciences convey the strong probative operativity of forensics. But forensics is by no means the exclusive preserve of scientific disciplines. Initiatives with a more culturalist and political flavour also use forensics to support social and legal interventions affecting human and international rights. Such is the mandate of the Forensic Architecture project directed by Eyal Weizman of the Centre for Research Architecture at Goldsmiths, University of London: “Forensic Architecture refers to the presentation of spatial analysis within contemporary legal and political forums. The project undertakes research that maps, images, and models sites of violence within the framework of international humanitarian law and human rights. Through its public activities it also situates forensic architecture within broader historical and theoretical contexts.”9 The research methods of Forensic Architecture are the following: conducting missions in politically sensitive locations (Libya, Gaza, Guatemala, Pakistan, and other places), making surveys using surveillance technologies – satellite imagery, gps data, ground-penetrating radar – collecting images from alternative media (cellular phones, citizen journalism), and interviews with witnesses. Then a field study is conducted to gather information. These investigations are, furthermore, indissociable from the organization of forums for public discussion in the form of seminars, congresses, publications, and exhibitions. The public dimension of these activities revives the primary meaning of the term “forensic.” From the Latin forensis, which means “public square, forum,” forensics is in part linked to the idea of legal argument, which is defined as a statement of facts for a court hearing. With the goal of persuading and convincing, legal argument proceeds from the Aristotelian concept of rhetoric – whence the importance, in the genre of “legal” oratory, of demonstration: “To highlight the controversial point [in a dispute], one must perform a demonstration,” wrote Aristotle in the third book of his Rhetoric.10

As a consequence, forensics cannot be reduced simply to a technique that establishes evidence. More than a procedure, forensics is a discursive process whose claims to the truth must be taken with a grain of salt. Yet the rhetorical dimension historically attached to forensics seems to have been forgotten by contemporary forensics, which assigns it a function that is, above all, pragmatic. The cultural, architectural, and, especially, artistic interpretations of forensics bring to mind this fundament by stressing the imaginary potentialities of probative systems.

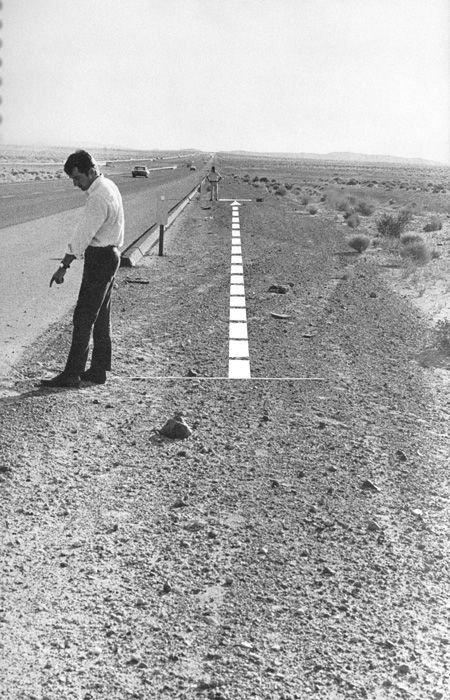

Toward a Forensic Aesthetics. The critical discourse on the visual arts is not to be outdone, because here again forensics terminology imposes its interpretive perspectives. A conclusive example of this new pre-eminence of forensics imaginaries in art criticism and theory is supplied by the exhibition “Scene of the Crime,” organized by Ralph Rugoff and presented at the Armand Hammer Museum of Art and Cultural Center in Los Angeles in 1997. This exhibition traces the evolution of art on the American west coast since the 1960s, through the prism of an interpretation imbued with forensics methods. Rugoff’s proposal consists mainly of reminding viewers that conceptual and post-minimalist arts proceeds from an indexical conception of the artwork characterized by the production of traces, remains, and clues rather than of completed objects designed for visual appreciation alone. This conception tends to liken artworks – those by, among others, Ed Ruscha, Barry Le Va, Vija Celmins, and George Stone and Abigail Lane, to name the most recent ones – to enigmas subject to elucidation. The aesthetic reception thus becomes comparable to an investigation insofar as the artworks in question resemble situations subjected to the viewer’s adductive reasoning. “The viewers,” explains Rugoff, “could no longer be mere viewers but had to function like detectives or forensic technicians, attempting to reconstruct the activities and ambiguous motivations congealed in physical artifacts. And, as at a crime scene, one encountered a diffuse field of clues rather than a coherent organized subject.”11 By re-enacting the artistic action, the viewer is thus a stakeholder in an artistic project presented in the metaphoric form of a crime scene. This active position of the viewer is summoned notably in Ed Ruscha’s Royal Road Test (1967), which consists of photographic documentation of the remains of a Royal typewriter thrown onto Route 66 from a 1963 Buick Le Sabre at 5:07 p.m. As much as the statement of the spatio-temporal coordinates is essential to the qualification of this artistic action, it is essential because it confers upon it the nature of a legal occurrence report. Ruscha deliberately exploits this register with the production of radically constative photographs whose legends attest, if more testimony is needed, to the categorically documentary function of forensic images: “Point of Impact,” “Illustrations showing distance wreckage traveled.” Rugoff does not hesitate to speak in terms of a forensic aesthetic with regard to this work, as well as all of the images brought together for “Scene of the Crime.” His intention is not at all to group them under a single label or, even less, to subordinate them to a common standard. Rather, he wants to rehabilitate the viewer’s speculative faculties, by identifying the viewer as a crime-scene technician, a forensic anthropologist, a detective – in short, an expert. There’s no doubt that the forensic reinterpretation of conceptual art and the viewer’s requalification as an expert are linked in part with the rise to preminence of the forensic paradigm in the 1990s.

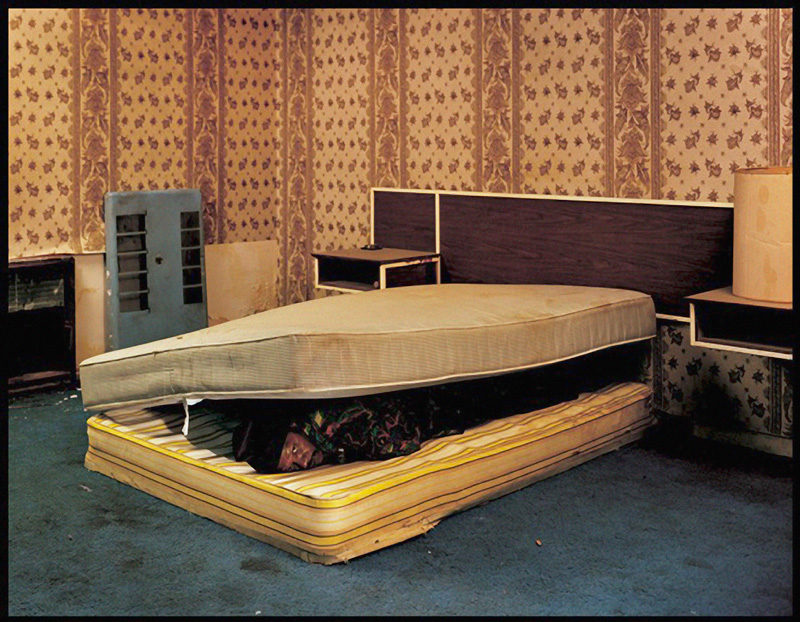

The Innocents. American artist Taryn Simon’s works, especially those in the series The Innocents (2002), are emblematic of how a contemporary artist incorporates the probative principles of forensics. In the summer of 2000, as she was executing a commission for New York Times, Simon decided to photograph people wrongfully sentenced to very long prison terms. This marked the first stage of Simon’s art project investigating the functions of the image and of visual testimony in the legal system. All of the subjects photographed by Simon were charged due to identification errors made by the victims of criminal acts: an erroneous correspondence between an individual and a composite sketch or identification, or a witness’s or victim’s faulty memory.12 A reconsideration of the value of visual “evidence” used in the process of charging the subject is central to Simon’s intention. Many of the individuals photographed by Simon were exonerated through dna analyses conducted following legal battles. Not only do the images produced and administered by the apparatus of justice pervert the process of identification, but they become, under the gaze of victims and police forces, catalysts for the most unjust criminal indictments. It took probing of the infravisible with forensic instruments for these people finally to obtain reparation. Simon’s The Innocents correlates two systems of evidence that are difficult to reconcile: on the one hand, the system based on speech and the victim’s memory; on the other hand, the system built by technoscience. Eyewitness testimony, as “an oral testimonial aid for reconstruction of past circumstances,”13 offers very limited reliability. As Renaud Dulong reports, psychologists have demonstrated the low aptitude of individuals to accurately reconstruct the details of a situation experienced, especially when it was traumatic. It has been observed that a physical assault, for example, renders partially inoperative the cognitive faculties responsible for mnesic storage of the representation of events. This observation has led to a form of devaluation of eyewitness testimony and concomitant over-valuing of indicial evidence (dna, various types of trace evidence, and so on) gathered by technical and scientific police officers. Given the rise to pre-eminence of material evidence, Dulong is right to express the fear of seeing historical live witnesses impeached and personal certifications, which are in fact indispensable to the establishment of the public discourse, invalidated. Simon does not propose to set two probative systems – one, fallible, based on the rhetorical powers of the image and testimony; the other, incontestable, supported by the rigour of scientific and technical rigour – in opposition. Nor does she offer an apologia for forensics or turn to an ideological critique of forensic uses of the image. Her intention is completely different. Thus, the position that she accords to the speech of innocents in the framework of her project – whether in the form of filmed accounts or of extensive legends – attests to the still-operative value of the testimonial form. The Innocents brings audibility back to the stifled speech of victims of legal errors.

As the photographic or graphic image is called into question in the charging process, Simon’s work also aims to return to the innocent the power to administer the visual representation of the damage done to them. Simon asked these men to choose the place where they would be photographed – a place significant in terms of the injustice that they suffered: the site of their arrest, the location where the crime occurred, the area where they were when the crime occurred, or a similar place. By revisiting these sites, marking them with the seal of their finally acknowledged innocence, these men find themselves, in a way, re-enacting the circumstances behind their personal tragedy. In the legal sphere, a re-enactment is a legal act aiming to reproduce all of the acts committed during the perpetration of a crime. The legal re-enactment shows how the events unfolded, verifies hypotheses, contradicts or confirms the testimony, or highlights technical and material impossibilities. It is an illustration in that it confers a tangible and intelligible dimension on past events. Yet, like any illustration, the procedure involves a share of invention, attributable to both its execution – for example, the performance of the protagonists in the drama (criminals, police officers, witnesses, and eventually the victims) or, at least, the stand-ins mandated by the judge on the day of the re-enactment – and its future instrumentalization by the defence or the prosecution during a trial. The illustrative and rhetorical dimension of the re-enactment has been the topic of some criticism by forensics experts, who want to establish a clear distinction between re-enactment and reconstruction. Criminalist William Jerry Chisum, author of an authoritative book on courtroom reconstructions, defines reconstruction as a scientific method that calls upon specialized knowledge (anthropology, entomology, forensic medicine, biotechnology, and so on) with the goal of determining the actions and events surrounding the perpetration of a crime.14 The witnesses’ statements, a suspect’s confessions, the victims’ testimonies, the examination of clues and incriminating evidence, the results of toxicology analyses, and autopsies supply the raw material for reconstructions, which proceed from the synthesis of various areas of expertise that, in isolation, would not be able to paint an overall picture of a crime.

Unlike reconstruction, re-enactment is, in Chisum’s view, devoid of scientific foundation. He defines it as a procedure in which the participants are called upon to mimic an action related to an event or a series of events. It serves as a complement to a reconstruction that a jury might, for example, find too technical or insufficiently explicit. Its goal being to present the likely conditions of a given situation, it fulfils an illustrative function. This gives it, Chisum feels, a subjective dimension likely to lead jury members astray.15 Because the re-enactment is an illustration, caution should be exercised with regard to the performed or visual representations reproducing the circumstances of a crime, according to Chisum. Yet the subjective nature inherent to re-enactment is exacerbated in Simon’s work. Far from conforming with any legal protocol, the men decide on the forms of their enactment: Troy Webb, dressed in a suit, stands in the woods where the assault took place; Tim Durham sits, holding a rifle, in the middle of a firing range, the site of the alibi; Clyde Charles leans on the hood of his car outside a prison where he was incarcerated for seventeen years and where his brother Mario, convicted of the crime, now resides; Ronald Cotton stands on the sandy bank of a stream, his arm around the shoulder of Jennifer Thomson, the victim of the rape for which Cotton was unjustly convicted. Without exception, the men look at the camera as if they are looking straight into the accusing eye of the legal system that had once been riveted on them. The photographs resulting from this ritual attest to the subject’s retaking control of the proceedings of his own figuration. The Innocents restores the subject’s moral integrity at the same time as it rehabilitates the testimonial power of the image, by returning it to the core of debates over contemporary figurations of guilt and innocence.

Registers of Expertise. Simon’s example-matrix shows the extent to which images remain at the epicentre of fundamental questions involving beliefs and truth systems. As emblematic as it is, The Innocents nevertheless intersects with the concerns of a number of contemporary artists. For instance, Emmanuelle Léonard (Homicide, détenu vs détenu, archives du palais de justice de la Ville de Québec, 2010), as Gaëlle Morel explains in this portfolio, confers visibility on images normally confined exclusively to the sphere of legal administration. The transposition into the public domain of these confidential images takes the form of a reinterpretation of the photographic protocols of the police investigation, whether through systematic hanging borrowing from the conceptual parameters of the grid, the substitution of black and white for the original colour of the police pictures, or the subtraction of the instructions behind the production of these archival photographs. The probative value of police images is also central to the intention of William E. Jones, who, with Tea Room (1962/2007), a found film showing clandestine sexual activities between men that took place in the summer of 1962 in public restrooms in Ohio, questions the status of the defamatory image. Produced for the fbi, this film was meant to be evidence of acts of sodomy, which, at the time, was punishable by a prison sentence of one year minimum. The functions of the image as informant are discussed in my essay on Jones’s project.

Also borrowing from a “third party” object for her work, Corinne May Botz (The Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death) photographed miniature dioramas, reconstructions of crime scenes produced for educational purposes in the 1940s by Frances Glessner Lee, founder of the Harvard University’s Department of Legal Medicine and honorary police captain of the New Hampshire State Police. By amplifying certain details and placing them in a narrative through ingenious reframings, Botz puts the didactic dimension of these set pieces in jeopardy – compromising the imperatives of forensic objectivity, as Alexis Lussier observes in “A Residue of Uneasiness.” Standard Operating Procedure (2008), by the documentary filmmaker Errol Morris, is the subject of Susan Schuppli’s essay. The film looks back at the scandal of torture and abuse perpetrated at the Abu Ghraib prison in 2004 and uncovered through the souvenir photographs of the soldiers involved. The key scene of the documentary shows how a special agent from the Criminal Investigation Division discovered the true chronology of the events by studying the metadata associated with the digital files of the incriminating images. Using this observation, Schuppli exposes the dichotomy between two testimonial systems: the speech of the participants in the affair, on the one hand, and the implacable truth of the data – which, in their turn, ended up becoming supporting evidence. Encoding as a source of truth is also at the heart of Suspect Inversion Center (sic), a project that Paul Vanouse started in 2011, and this is the subject of Marianne Cloutier’s essay. The main activities of the sic – performances, laboratory analyses, exhibitions – are intended to investigate the truth-telling power commonly associated with dna – biotechnological evidence said to be irrefutable. Finally, the pre-eminence of forensics as an analytic model reaches as far afield as the masterpieces from Canadian art history, as Phil Chadwick has seized upon paintings by Tom Thomson to apply his methods borrowed from forensic meteorology. Armed with diagrams and animations, Chadwick, himself a meteorologist, has undertaken to determine the climatic conditions prevailing in the landscapes painted by Thomson – flouting, as Bénédicte Ramade notes, the aesthetic considerations of rigour.

If there is a common denominator in all of the art practices brought together in this portfolio, it is perhaps this: the affirmation of an aesthetic-legal paradigm for art. This paradigm is characterized, it would seem, first by the posture of expert that the artists adopt by using evidence produced by third parties. The posture of detective is absent from these artists’ modus operandi: no inquiry or compilation of clues was involved in the creation of their artworks. The posture of expert, or even of litigant, serves their purpose better. Recognition of the viewer’s expertise also qualifies this paradigm in that the works appeal to the viewer’s judgment. Confronted with procedures for establishing the truth, the viewer’s function of arbitrator with regard to the image is re-established. While absolute proof would seem to have irremediably escaped the naked eye, art now restores the belief in the visible.

* The purported skull of Josef Mengele was displayed for reporters and news crews on 6 June, 1985 in Embu, Brazil. It is believed that notorious Nazi death-camp doctor’s bones were unearthed in a small cemetery in Brazil under a grave marker labeled Wolfgang Gerhard.

2 See Vincent Lavoie, “La rectitude photojournalistique. Codes de déontologie, éthique et définition morale de l’image de presse,” Études photographiques, no. 26 (November 2010): 3–24.

3 See Andrew R. W. Jackson and Julie M. Jackson, “Forensic Science in Court,” in Forensic Science (Harlow: Pearson Education, 2004), pp. 419–39; Edward M. Robinson, Crime Scene Photography (Boston: Academic Press and Elsevier, 2007); Tim Thomson, “The Role of the Photograph in the Application of Forensic Anthropology and the Interpretation of Clandestine Scenes of Crime,” Photography & Culture, vol. 1, no. 2 (November 2008): 172.

4 See Vincenzo A. Sainato, “Evidentiary Presentations and Forensic Technologies in the Courtroom: The Director’s Cut,” Journal of the Institute of Justice & International Studies, vol. 9 (2009): 38–52.

5 See Michele Byers and Val Marie Johnson (eds.), The csi Effect: Television, Crime and Governance (Plymouth, uk: Lexington Books, 2009. Elizabeth Harvey and Linda Derksen observe a number of corollary effects of this syndrome: increased registration in criminology faculties, popular belief in the irrefutability of scientific evidence, the impression that tv programs have an informative aspect. See also Chandler Harriss, “The Evidence Doesn’t Lie: Genre Literacy and the csi Effect,” Journal of Popular Film and Television, vol. 39, no. 1 (2011): 2–11.

6 The term forensique is used in French in disciplines as varied as entomology, biology, and psychiatry. See Christine Frederickx et al., “L’entomologie forensique, les insectes résolvent les crimes,” Entomologie faunistique – Faunistic Entomology, vo. 63, no. 4, 2011 (2010): 237–49; Françoise Fridez, Analyse d’adn mitochondrial animal: vers une exploitation forensique des poils d’animaux domestiques, doctoral dissertation in forensic science, Université de Lausanne, 2000; Bruno Gravier, “Psychothérapie et psychiatrie forensique,” Revue Médicale Suisse, vol. 6, no. 263 (2010): 1774–78.

7 Quoted on the Web site for the exhibition Visible Proofs: Forensic Views of the Body, National Library of Medicine, Bethesda, Maryland, www.nlm.nih.gov/visibleproofs/galleries/cases/disappeared_image_2.html. On Clyde Snow’s participation in the forensic identifi-cation of the remains of Josef Mengele, see Eyal Weizman and Thomas Keenan, Mengele’s Skull.

8 See issue no. 132 (2010/2) of the magazine Langage & Société on the theme “Linguistique légale et demande sociale : les linguistes au tribunal.”

9 www.forensic-architecture.org/.

10 Aristotle, Rhétorique III, 1417 b, translated by Médéric Dufour and André Wartelle (Paris: Les Belles Lettres, 1973), p. 89 (our translation).

11 Ralph Rugoff, “More than Meets the Eyes,” in Scene of the Crime (Cambridge: mit Press, 1997), p. 61.

12 See Taryn Simon, The Innocents (New York: Umbrage Edition Books, 2003), p. 42; see also David Courtney and Stephen Lyng, “Taryn Simon and The Innocents Project,” Crime, Media, Culture, vol. 3, no. 2 (2007): 185–86. I would like to thank Mirna Boyadjian, master’s student in art history at uqam and author of a thesis devoted to the work of Taryn Simon, for having told me about the existence of this article.

13 Renaud Dulong, Le témoin oculaire. Les conditions sociales de l’attestation personnelle (Paris: Éditions de l’École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales, 1998), p. 9 (our translation).

14 W. Jerry Chisum and Brent E. Turvey (eds.), Crime Reconstruction (Burlington, Mass.: Elsevier Academic Press, 2007).

15 Ibid., p. 197.

Vincent Lavoie is a professor in the department of art history at UQAM. His research, combining photography, aesthetics, and art history, deals with contemporary representations of the event and photographic forms of visual testimony. This area of research interest has led to the production of a number of publications, including Photojournalismes. Revoir les canons de l’image de presse (Paris: Éditions Hazan, 2010) and Imaginaires du présent. Photographie, politique et poétique de l’actualité (Montreal: Cahiers ReMix Figura, 2012, online).