[Fall 2011]

by Zoë Tousignant

In the fall 2010 issue of its magazine M, the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts (MMFA) announced that it had recently acquired significant bodies of Quebec photography, ranging from the 1960s to the 1980s. “The Museum’s Collection Grows by Leaps and Bounds,” declared the article’s subtitle – a statement that, since it referred to the photography collection in particular, was both surprising and exciting.

The new acquisitions of Quebec photography from the 1960s to the 1980s are thus part of the institution’s current recognition… photographic imagery of all kinds, and these acquisitions have added considerably to the growing photography collection…

Although the MMFA boasts an encyclopedic and international collection of art and artefacts from Antiquity to the present day (including a remarkable collection of decorative arts), it has not been known for its enthusiastic collecting practices in the realm of photography. This, in spite of the fact that Canada’s most famous nineteenth-century photographer, William Notman, was among the prominent and influential figures in the formation of the Art Association of Montreal, as the museum was originally called. It was not until the turn of the twenty-first century, in fact, that the MMFA began to acquire photographs with any degree of consistency.

This nevertheless has not prevented the MMFA from participating in Canada’s photographic history as an eminent site of display. Indeed, during the century that separated Notman’s initial involvement from the gradual increase of photographic collecting that has been taking place since the early 2000s, the museum has played host to numerous photography exhibitions – exhibitions that reflect the idiosyncratic nature of the history of photography in Quebec and in Canada.

In the fall 2010 issue of its magazine M, the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts (MMFA) announced that it had recently acquired significant bodies of Quebec photography, ranging from the 1960s to the 1980s. “The Museum’s Collection Grows by Leaps and Bounds,” declared the article’s subtitle – a statement that, since it referred to the photography collection in particular, was both surprising and exciting.

Although the MMFA boasts an encyclopedic and international collection of art and artefacts from Antiquity to the present day (including a remarkable collection of decorative arts), it has not been known for its enthusiastic collecting practices in the realm of photography. This, in spite of the fact that Canada’s most famous nineteenth-century photographer, William Notman, was among the prominent and influential figures in the formation of the Art Association of Montreal, as the museum was originally called. It was not until the turn of the twenty-first century, in fact, that the MMFA began to acquire photographs with any degree of consistency. This nevertheless has not prevented the MMFA from participating in Canada’s photographic history as an eminent site of display. Indeed, during the century that separated Notman’s initial involvement from the gradual increase of photographic collecting that has been taking place since the early 2000s, the museum has played host to numerous photography exhibitions – exhibitions that reflect the idiosyncratic nature of the history of photography in Quebec and in Canada.

Of note are the “International Salons of Photography,” organized by the Montreal Camera Club and shown within the Art Association’s walls from the 1940s to the 1960s. While the works presented may perhaps be judged non-art due to their amateur status, the catalogues published to accompany the salons suggest that the local photographers active during this era – people such as Blossom Caron, Paul Christin, and Georges A. Driscoll – grasped the potential of such showcases. If nothing else, by providing their viewers (and reviewers) with opportunities to ponder the medium’s expressive potential, these exhibitions contributed to the budding Canadian photographic discourse that was to establish itself on firmer ground in the following decades.

Also notable is the role that the MMFA has played as a prized venue for the exhibitions disseminated by Le Mois de la Photo à Montréal. In collaboration with this organization, the museum has, over the past fifteen years or so, presented some of the best photography exhibitions that Montreal has seen. Particularly impactful for me have been the Gabor Szilasi retrospective, curated by Mois de la Photo’s Franck Michel and presented in 1997, and the more recent Tracey Moffatt show, mounted for the biennale’s 2005 edition.

Yet despite the MMFA’s regular exhibiting of photography, by the turn of the millennium – as the medium was shedding its analogue skin with increasing resolution – the institution had only around 150 photographic works to call its own. It seems that a simple lack of interest was the cause of this diminutive collection, but, as explained to me recently by Diane Charbonneau, the museum’s curator of contemporary decorative arts, the trend would be gradually reversed after the arrival of Guy Cogeval as director of the museum in 1998. “Guy Cogeval was keen on photography,” says Charbonneau, and during his tenure many important acquisitions were made, especially within the sphere of contemporary photo-based artworks.1 Significantly, this momentum has been maintained by the current director and chief curator, Nathalie Bondil, and has even been taken up a notch thanks to her enthusiasm for Quebec art in general.

The new acquisitions of Quebec photography from the 1960s to the 1980s are thus part of the institution’s current recognition of – and seemingly unquenchable gusto for – photographic imagery of all kinds, and these acquisitions have added considerably to the growing photography collection, which now totals over 1,500 works. The task of managing the collection is divided among several of the museum’s curators, including Stéphane Aquin, Curator of Contemporary Art; Anne Grace, Curator of Modern Art; and Diane Charbonneau, who is the key person in charge of steering the acquisition process.

That Charbonneau’s principal field of research is decorative arts can be seen as an advantage rather than a disadvantage, for her training and expertise have helped to shape her under-standing of photographs as complex objects rather than as purely two-dimensional “windows onto the world.” Her approach, I might add, is in tune with the “material turn” taking place in contemporary photographic studies, a turn heavily influenced by the writings of photography historian Geoffrey Batchen, material culture historian Elizabeth Edwards, and anthropologist and art historian Christopher Pinney.2 In fact, these authors, who share a belief that photography’s materiality is central to its identity and reception, have arguably had a hand in the now-common championing of vernacular photography within both museums and the academic world.

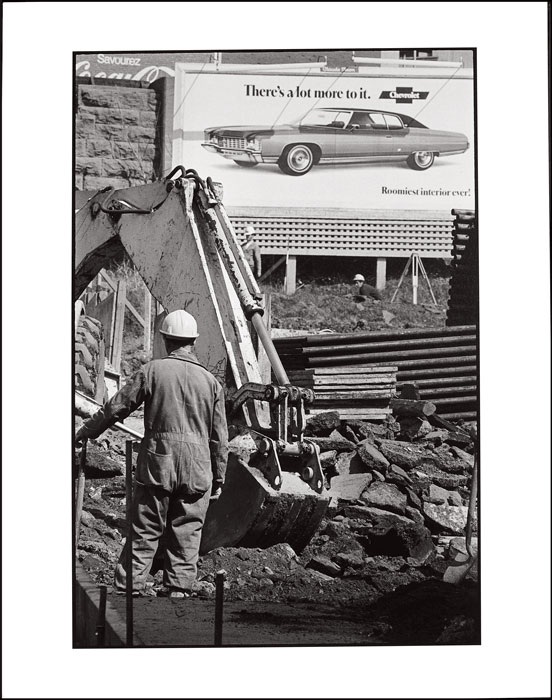

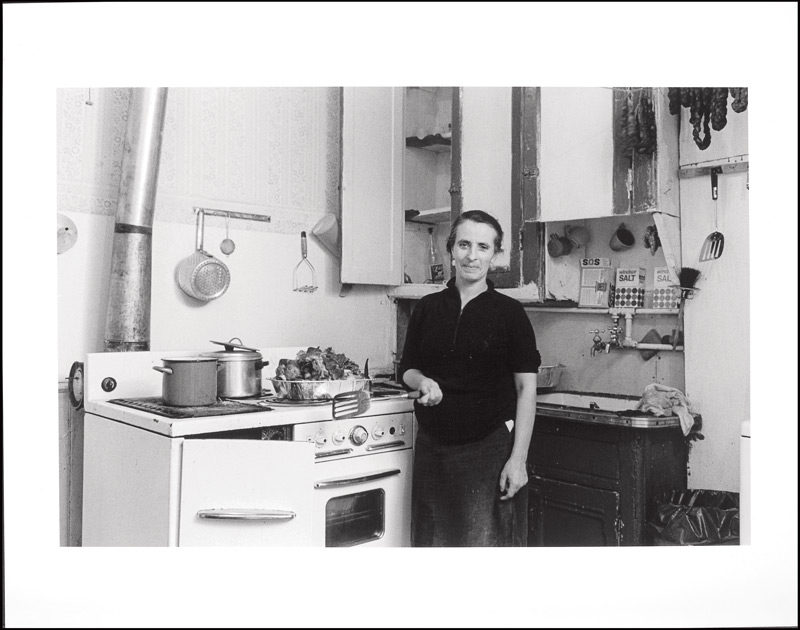

Charbonneau’s individual adherence to this approach may also have been a factor in the MMFA’s decision to acquire images that fall under the rubric of documentary photography. Seeing photographs depicting life in Quebec during the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s as complex objects rather than simply as conveyors of historical information must surely have a positive impact on their status as art objects. The “art vs. documentary” debate has been played out ad nauseam throughout the medium’s 170-year history, but it is still surprising that a museum until recently unconvinced of photography’s validity as an art form has wholeheartedly embraced a period in the history of Quebec photography that is defined primarily by documentary practices – a period that precedes the more self-consciously subjective strategies that would take over from the mid-1980s onward.

Or perhaps it isn’t surprising – not, at least, when one considers the background of the other key person responsible for making these acquisitions a reality. Marcel Blouin, for the past ten years director of Expression, Centre d’exposition de Saint-Hyacinthe, was hired by the MMFA as a researcher/consultant for this acquisition project, and he has been central in determining its nature and scope. As Blouin recently told me, his mandate has now been expanded from dealing with the period from the 1960s to the 1980s to covering the evolution of documentary photography in Quebec (with a particular emphasis on Montreal) from the 1960s to the present day. Concerned with bringing a distinct orientation to the project, he is interested in tracing the development of the documentary genre from what he sees as a preoccupation with the “we” to a focus on the “I” – or, put differently, from an objective to a subjective mode of image making. This shift in emphasis, which can sometimes be discerned within the span of an individual photographer’s career, is also, for Blouin, representative of a more general transformation that has occurred within Quebec society over the past thirty years.

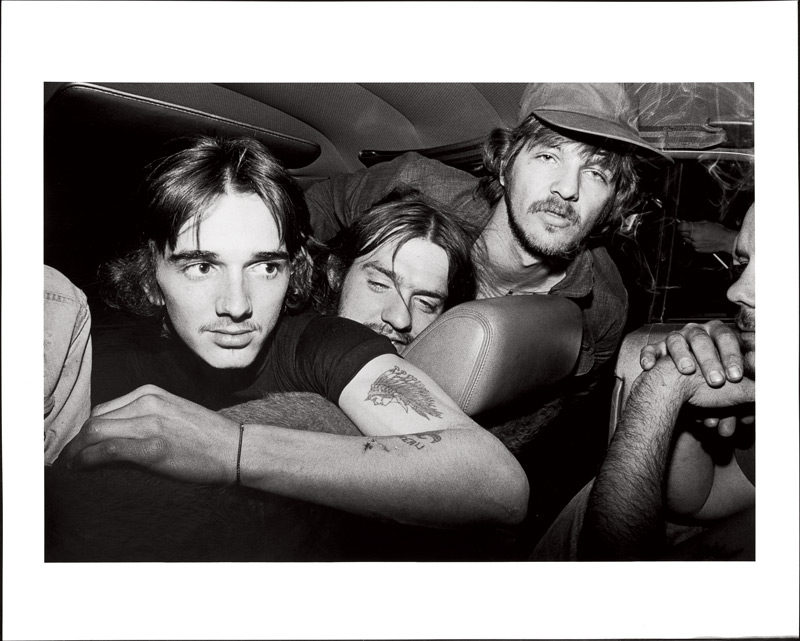

The photographers whose works have been acquired by the MMFA thus far – almost exclusively by donation – are Alain Chagnon, Roger Charbonneau, Brian Merrett, and Gabor Szilasi. Several other acquisitions (of photographs by John Max and Normand Rajotte, for example) are underway, and many more have yet to be set in motion. On behalf of the museum, Blouin has been working closely with these photographers in an effort to cast a retrospective eye over their careers and pick out certain key moments that appear to him significant for the history of documentary photography in Quebec. The longer he spends on the project, the more exponentially it seems to grow.

Marcel Blouin is quick to affirm that he does not perceive the shift from “we” to “I” – which essentially reflects a turn against a more socially conscious or humanitarian understanding of documentary photography – from a nostalgic point of view. Yet he expresses disappointment over the reality that very few photographers working today record the world around them using the methods associated with social documentary practices (which include a prolonged, almost activist engagement with a chosen subject), and he is critical of the fact that this approach to photography is not valued by the funding institutions that grease the wheels of Canada’s art world. “It’s unfortunate,” he says, “because I think that a country that does not document the world in which we live . . . well, that’s just foolish.”3

It appears that the tide had already begun to turn when a very young Blouin arrived on the Montreal photo scene in the early 1980s. Known as the founder of Vox Populi, the non-profit organization that created Ciel variable, Le Mois de la Photo à Montréal, and the artist-run centre now known as VOX, centre de l’image contemporaine, Blouin was part of an energetic team of artists and cultural workers who, from 1985 onward, were to have a lasting impact on Quebec’s photographic community. By the time the first edition of Le Mois de la Photo à Montréal was mounted, in 1989 (to commemorate the medium’s 150th anniversary), the emphasis on more personal or artistically inclined photography was becoming increasingly prevalent.

The origins of Vox Populi were nevertheless closely linked to the kind of documentary photography that has a clear social purpose. As Blouin recounts it, the organization had its roots in a collective for unemployed youths, the Collectif des jeunes sans-emploi de Saint-Louis-du-Parc, which was based in a room in the old YMCA building on the corner of Park Avenue and Saint-Viateur Street. Armed with a newly acquired degree in social sciences from the Université de Montréal, Blouin worked to bring awareness to the problem of youth unemployment being faced by Quebec society in the early 1980s. Many of the people involved in the collective were interested in the arts (photography, but also graphic design and literature), and together they mounted a photography exhibition around the theme of unemployment. The exhibition, “Sans honte et sans emploi,” toured throughout Canada, mainly to union congresses, and, significantly, drew many photographers to the organization that would re-emerge shortly after as Vox Populi.

Also significant, from the vantage point of the present, is that the photographers whose images have so far been acquired by the MMFA in collaboration with Blouin are predominantly (with a couple of exceptions) members of the baby-boom generation – the generation that came of age in the 1960s and 1970s and witnessed first-hand the dramatic changes taking place in Quebec and Canada at that time. The photographs by Alain Chagnon and Roger Charbonneau, for example, which were the first to be acquired, document the faces and places of an era that my own generation – “les enfants des baby boomers” – can only imagine through rose-coloured glasses and emulate, rather feebly, via a taste for retro music and fashion. Such an era, when a desire to “change the world” was not met by ridicule or apathy, is a reality that my generation will never know. For good or bad, it was a period of great upheaval, and we can be thankful that photographers such as Chagnon and Charbonneau were there, cameras aimed for posterity.

It is this upheaval and the changes it engendered that the MMFA is seeking to represent with its growing collection of Quebec photography. And it is perhaps this emphasis on the evolution of the documentary genre that will come to set its collection apart from those of other Canadian institutions. One thing is certain: with regard to the photographic collecting practices of the museum, these acquisitions – and those to come – represent a great leap forward.

2 See especially Geoffrey Batchen, “Vernacular Photographies,” in Each Wild Idea: Writing, Photography, History (Cambridge: mit Press, 2001), pp. 57–80; Elizabeth Edwards and Janice Hart, “Introduction: Photographs as Objects,” in Photographs, Objects, Histories: On the Materiality of Images, ed. Elizabeth Edwards and Janice Hart (New York and Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, 2004), pp. 1–15; and Christopher Pinney, “Notes from the Surface of the Image: Photography, Postcolonialism, and Vernacular Modernism,” in Photography’s Other Histories, ed. Christopher Pinney and Nicolas Peterson (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2003), pp. 202–20.

3 Marcel Blouin, interview with the author, 18 April 2011.

Zoë Tousignant is a Ph.D. student in art history at Concordia University. She holds a master’s degree in museum studies from the University of Leeds. Her doctoral research concerns photographic modernism in Canadian illustrated magazines between 1925 and 1945, and she is currently part of a team led by Martha Langford researching the memoriography of Canadian photographic history.