[Fall 2013]

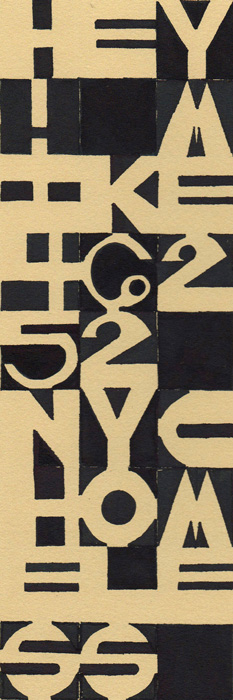

In the autumn of 2012, a large brown envelope addressed to me arrived at my apartment. Inside it was a signed inkjet print of a colourful typographic exercise, announcing via an enigmatic sentence – hey mike please wipe up any spills that may occur1 – the genesis of the latest project by Montreal artist Karen Elaine Spencer.

Created in New York in 2012–13, during a six month residency offered by the Canada Council of the Arts in collaboration with the International Studio and Curatorial Program, Spencer’s hey! mike project is built around a series of actions similar to those undertaken during her previous projects, which were presented in collaboration with the artist-run centres Dare-Dare (Montreal), Articule (Montreal), Praxis (Sainte-Thérèse), and Le 3e impérial (Granby). The taking and sharing of notes, the writing of short sentences in ink on various supports, the artist – and, by extension, her words – wandering in the public space, the taking of documentary photographs and videos, and the use of the mails, Web sites, and various social media, such as Twitter and Facebook, are all communicational strategies that Spencer uses to question the artist’s role in society and our relationship with the transitory, the city, the habitat, citizenship, power structures, the established order, and politics.

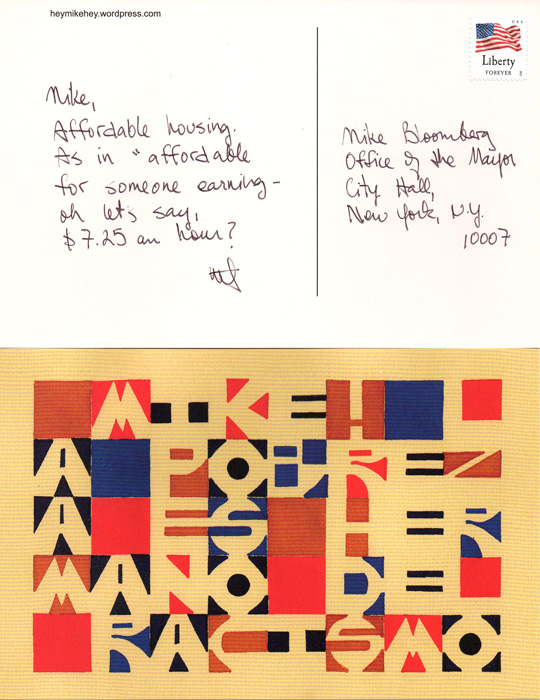

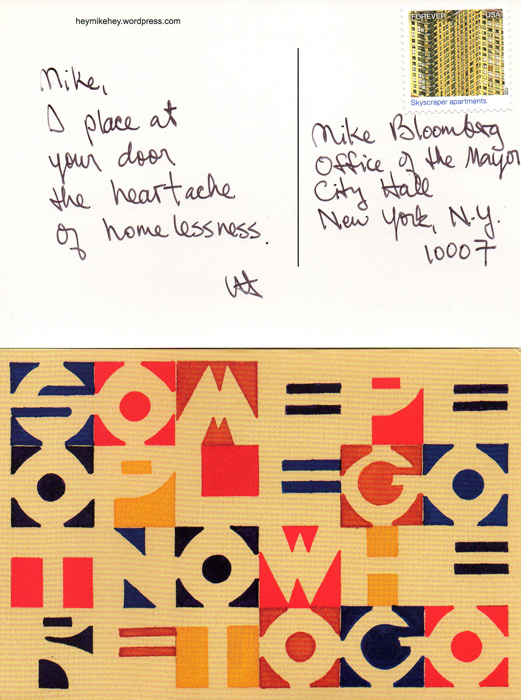

In hey! mike, Spencer more directly observes homelessness in New York, a potentially invisible social and economic condition that, due to its furtive nature, does not draw sustained media attention. The central character targeted by the project is Michael “Mike” Bloomberg, mayor of New York, the tenth-richest man in the United States, a notable patron of the arts and philanthropist, whom the artist engages in a multi-platform conversation on the subject.2 Here, Bloomberg is held up as the embodiment of economic and political power, the face of a sprawling and polarized city.

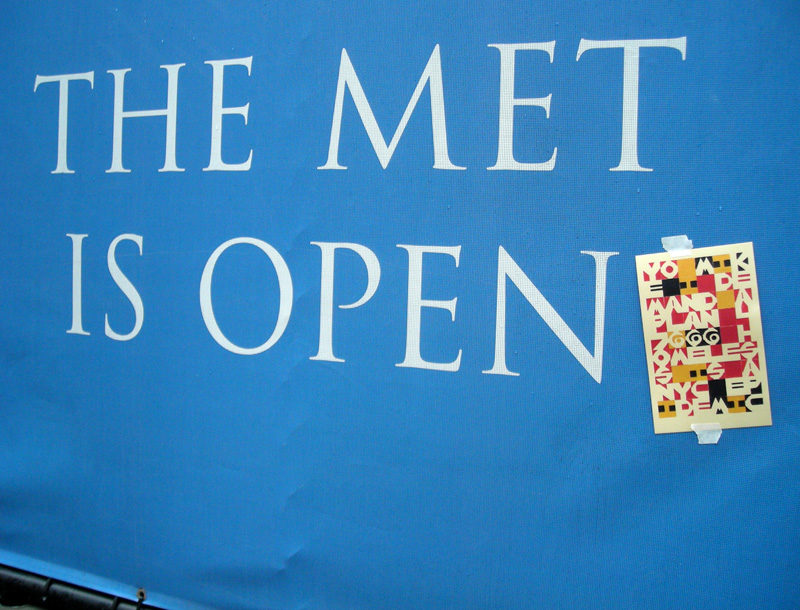

Far from instrumentalizing the issue of homelessness, Spencer looks at it from every angle with subtlety and honesty, questioning our collective responsibility in the face of the phenomenon and directly challenging those in positions of authority. Refusing to play the “public art” game by spending energy trying to carve out a place among invasive forms of urban visual spectacle, Spencer deploys a series of discreet tactics that mirror the invisibility of homelessness while trying to reflect on another form of public discourse – a fragmented and atomized one. She thus deploys a conception of the public space similar to Jürgen Habermas’s definition of that space, as resulting from a “process during which the public, composed of individuals using their reason, reappropriates the sphere controlled by the authority and transforms it into a sphere in which criticism is exerted against state power.”3 Through postcards and other messages sent in a variety of ways, Spencer outlines the ghostly presence of Bloomberg, constantly named but resolutely absent.

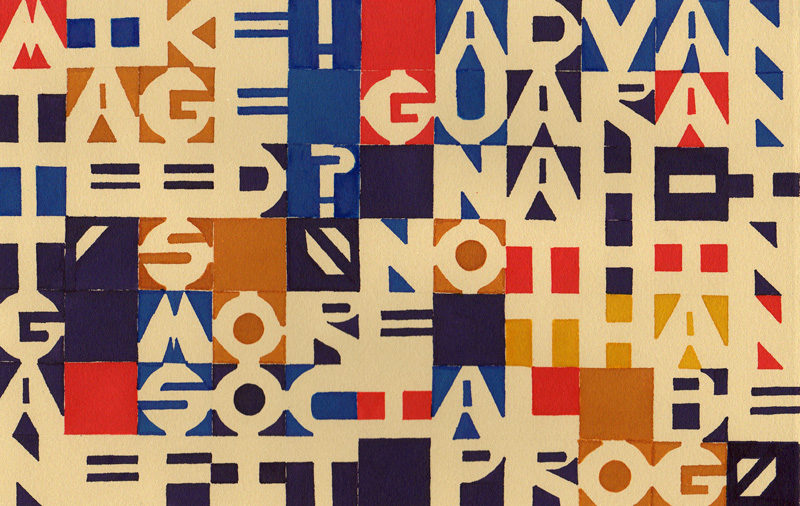

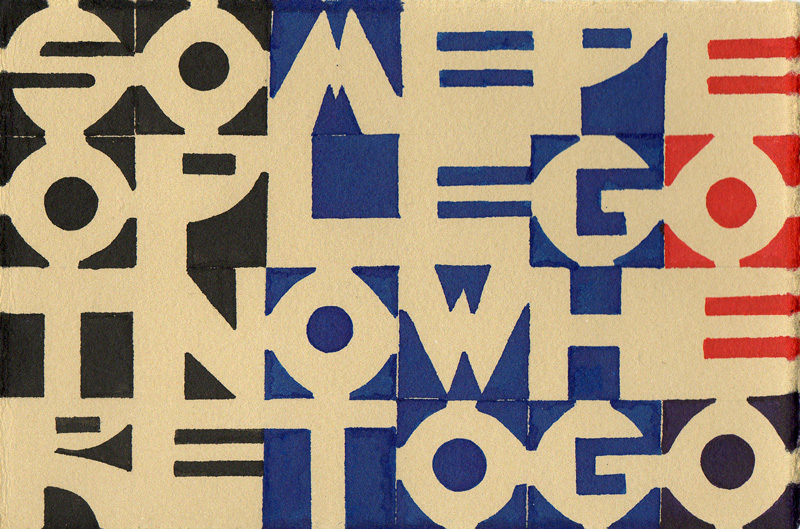

The use of the postcard, emblematic of Spencer’s work, has many purposes. First, it situates and dates the artist’s intervention. The symbol of a private exchange that transits through a public system, it materializes or makes visible an art project’s process of mediation and potential creation of communities.4 It “spatializes discourses” by materializing the exchange between two actors and “textualizes” the space of the image by replacing the photograph that usually occupies one side of the postcard with a printed sentence.5

The history of the postcard is intrinsically linked to the advent of photography and, more broadly, to the development of industrial and cultural modernity. Its use evokes the possibility of travel and signals the establishment of communications and information technologies in Western society, making tangible the constant flux between the constitution of a private domestic space and a public political space, between the constitution of the Self and the identification of the Other. By creating her own postcards on the basis of her typographic explorations, Spencer reverses the trend toward idealization and reinvests it with a different power – less that of ideological authority over a space than that of potential exchanges.

In this sense, the photographs taken by Spencer, published on the Web, also play the role of postcards. Documents of the performance, dated and situated evidence of travel, they make the artist’s ephemeral messages permanent. The taking of photographs in the public space, long considered a marker or indicator of urban spectacle, may seem to be in contradiction with the anti-spectacular nature of hey! mike. On the contrary, Spencer’s use of photography is evidence of a change in our relationship with the photographic. In a time when the practice of photography is becoming more and more private and commonplace, the value of a photograph is often attributed to its effective mediation in various networks rather than to the taking of the image in itself. In an ontological reversal, the photograph is no longer solely an image-consequence of the action in the public space, but truly causes the event, acts as its trigger. Spencer’s work becomes an opportunity to reflect on our relationship with representation, understood in both its aesthetic and its political senses.

In addition to the physical sites of her interventions and performances, the artist generally occupies space on the Web by creating micro-sites, hosted on the WordPress platform, in which she can document her research process and her actions in the city. For hey! mike, a blog describes the artist’s urban travels; the blog also shows the places where she pasted up postcards to be found, lists links to non-profit organizations that defend the rights of the homeless, and points to news items published in various media. The blog indicates an opening toward a different space, a site for potential discussions, and the virtual space is positioned not to disrupt the physical space but to complement it. Spencer’s role here is similar to that of a curator,6 responsible for arranging objects in space and juxtaposing the content from various sources through her own photographs and postcards.

At first glance, the site of intervention of hey! mike – composed of the city of New York, the site of production of works on paper, and the Web site created for the occasion – is more “functional” than physical; a constellation of virtual and real places, the site appears as a “process . . . a mapping of institutional and textual filiations and the bodies that move between them.”7 Given the fragility of the ephemeral objects (postcards and prints) that Spencer produces, the complexity of the relationships that she describes takes shape. This transition from a situated intervention to a series of actions made on a site that she constantly updates is exemplary of contemporary art practices, which challenge our relationship with the social, institutional, and cultural dimensions of a site.

However, the project bears a fundamentally phenomenological dimension, as it was formulated and developed in a context of residency, during which an artist is asked to be involved with an exhibition and production site. By strolling in the city, opening herself to the public space as she travels between the studio in Brooklyn and the apartment in Manhattan, Spencer questions the mandate of a residency and the public responsibility of the artist in her exterior intervention. How do we document our discovery of and relationship with this place? How important is an individual intervention in a city in which our status is transitory? How can we satisfactorily inhabit and be involved a place that is foreign to us and in which our presence is temporary?

Translated by Käthe Roth

2 Karen Elaine Spencer, hey! mike hey!, http://heymikehey.wordpress.com/.

3 Jürgen Habermas, L’espace public (Paris: Payot, 1993 [1978]), p. 63 (our translation).

4 Jacques Rancière, Le partage du sensible : esthétique et politique (Paris: La Fabrique, 2000).

5 Kwon, One Place, p. 29.

6 “blog as studio – artist as curator” is one of the phrases used by Spencer in the project, evoking the virtual space as physical space and the artist as organizer called upon to reflect and arrange the space.

7 James Meyer, “The Functional Site; or, The Transformation of Site Specificity,” in Space, Site, Intervention: Situating Installation Art, ed. Erika Suderburg (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2000), p. 25.

Daniel Fiset is a doctoral student in the Department of Art History at the Université de Montréal. His current research deals with conceptual and formal links between photography in contemporary art and visual culture. He is also interested in conservation of public art in Quebec and in situ art practices.