[Winter 2013]

By Vincent Lavoie

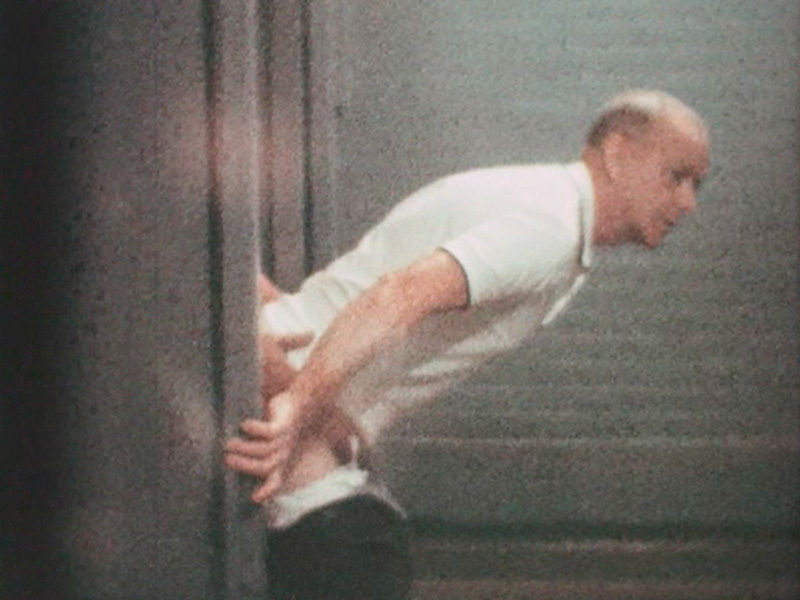

In the summer of 1962, the Mansfield, Ohio, police department, convinced that homosexual practices created a predisposition to perpetrate serious predatory crimes, decided to put the public restroom in a large park in its town under surveillance. The site was suspected of being the scene of clandestine sexual activities among men of various ages, origins, and social backgrounds. The police therefore undertook to surreptitiously document the comings and goings of these individuals, confident that they would be able to record, on 16 mm colour film, acts of sodomy – an offence then punishable with a minimum one-year prison sentence. For more than three weeks, a camera hidden behind a mirror in a towel dispenser in the restroom captured the criminal acts. Reports at the time praised the police force’s technical prowess in finally uncovering this “nest of bestial depravity,”1 the shame of Mansfield. Based on the images produced and submitted as evidence in a court of law, a number of men were convicted and incarcerated. The film was admitted into evidence on the express condition that no editing would be done. Some time later, the Highway Safety Foundation, a Mansfield organization that produced graphic films of collisions designed to deter reckless driving, used this raw material to make a film called Camera Surveillance to be used to train officers on similar stake-outs. The sound track accompanying a re-enactment of the methods used by Mansfield police officers consisted of a commentary vaunting the social utility of film in repression through the surveillance and filming of acts of sexual “deviance.” In its turn, this film became the raw material for a first work that William E. Jones devoted to police documentation of sexual activities by gays. Produced with a poor-quality copy downloaded from the Web, Mansfield 1962 (2006) is a condensed, monochrome, silent version of the original. The suppression of the incriminating commentary, the poor quality of the images, the black and white, and the editing combine to empty the document of its inquisitorial dimension. The production of this artwork was part of a major research project on documentary that led Jones to recover the unretouched 1962 version. From this film, he produced Tearoom (1962/2007), a 56 minute video of the original recording.

The sound track accompanying a re-enactment of the methods used by Mansfield police officers consisted of a commentary vaunting the social utility of film in repression through the surveillance and filming of acts of sexual “deviance.”

Tearoom puts the incriminating image on trial, on the one hand, by conserving confidential visual material produced under obsolete investigatory protocols and responding to bygone imperatives of moral hygiene, and, on the other hand, by bringing to light a form of defamatory discursiveness in which the images stand out as the main instruments of a sexual inquisition mixed with voyeurism. Putting these images on trial consists, first, of documenting the practical and legal conditions for their production. Having conducted his own inquiry, Jones reveals, in the publication accompanying the public presentation of Tearoom – by reproducing articles and documents related to this affair, as well as more recent confessions and testimonies – how sophisticated the operation was. On the technical level, the task involved creating optimal recording conditions: the walls of the restroom were repainted a light colour for better luminosity, more-powerful light bulbs were installed, a paper-towel dispenser was modified by putting a mirror without silvering in it, a hole was pierced in the door on which the dispenser was installed, and a police officer was stationed behind this door with a 16 mm camera. The trap was set at night, when the public restrooms in Mansfield’s Central Park were closed. On the logistical level, nothing was left to chance. Once the compromising images were made, the police officer used a walkie-talkie to give a colleague stationed in a neighbouring building a physical description of the suspect. A police officer on motorcycle then confronted the individual and obtained his identity and address under false pretences. The arrest took place several days later.2 Finally, the legal component of the operation had to be irreproachable. It was based on the admissibility of the images. The public restrooms contained sinks and urinals, but also closed cubicles, which constituted inviolable private spaces in the eyes of the law, unless the door was open or removed. That is why Tearoom shows mainly scenes taking place through a crack in the cubicle door – more precisely, in the margin separating the punishable offence from the legally untouchable act. It was within this legal framework that it was possible to produce these images. Then, the images had to be processed and distributed to the authorities concerned. A court order was required to force Eastman-Kodak, which professed shock at the obscene nature of the images, to hand over the film that it had developed.

Putting these images on trial also consists of investigating the resiliency of their function as informant. In Camera Surveillance, the Mansfield chief of police, C. W. Kyler, did not hide his satisfaction that evidence of this nature could be recorded in colour film, as if colour brought to the incriminating document an extra defamatory component that was helpful to his cause. Colour intensifies realism – a fact recognized by American courts since the 1940s.3 The probative virtues of colour thus participated fully in the incriminatory arsenal of the Mansfield police by adding a touch of calumny, because of its realism, to these masculine frolics, “so shockingly and authentically documented.”4 As a visual coming out, Tearoom puts into circulation private images that no one except the actors in the legal system was supposed to see. And for good reason: these shameful images, beyond the acts that they document, betray the voyeurism of an ambivalent operation. For, under pedagogical and moralistic cover, this repressive action has definitively been found to institute an unprecedented iconographic homoerotic repertoire.

Translated by Käthe Roth

2 For a complete description of the procedure, see John P. Butler, “No Discrimination,” in The Best Suit in Town (Punta Gorda, Florida: Royal Palm Press, 2001), reproduced in Jones, Tearoom, pp. 14–15.

3 See Edwin Conrad, “Color Photography: An Instrumentality of Proof,” Journal of Criminal Law, Criminology, and Police Science, vol. 48, no. 3 (1957): 321–32.

4 “Two Editorials,” p. 5.

William E. Jones is an artist and filmmaker who grew up in Ohio and now lives and works in Los Angeles. He has made two feature-length experimental films, Massillon (1991) and Finished (1997); several short videos, including The Fall of Communism as Seen in Gay Pornography (1998); the documentary Is It Really So Strange? (2004); and many installations. His work has been shown at the Cinémathèque française and the Musée du Louvre, Paris; the International Film Festival Rotterdam; Sundance Film Festival; the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles; and the Museum of Modern Art, New York. His films and videos have been the subject of retrospectives at the Tate Modern, London, in 2005; Anthology Film Archives, New York, in 2010; and the Austrian Film Museum, Vienna, and the Oberhausen Film Festival in 2011. His work is exhibited by David Kordansky Gallery in Los Angeles, Galleria Raffaella Cortese in Milan, the Modern Institute in Glasgow, and White Cube in London. williamejones.com

Vincent Lavoie is a professor in the Department of Art History at UQAM. His research, combining photography, aesthetics, and art history, deals with contemporary representations of the event and photographic forms of visual testimony. This area of research interest has led to the production of a number of publications, including Photojournalismes. Revoir les canons de l’image de presse (Paris: Éditions Hazan, 2010) and Imaginaires du présent. Photographie, politique et poétique de l’actualité (Montréal: Cahiers ReMix Figura, 2012, online).