[Winter 2011]

by Richard Baillargeon

Richard Baillargeon: The darkrooms that we knew in the days of analogue photography are now a thing of the past. Photographers have abandoned them for digital tools. How did this work on darkrooms start ?

Michel Campeau: I began the project in September 2005, after finishing a series of works on the post-industrial landscape.1 As a photographer, I had the sense of being caught in a squeeze between analogue and digital, and when I got the idea of photographing darkrooms and making a creative project of them, doing it with a digital camera seemed obvious. I liked the instantaneity of visualization offered by the process, and I liked the digital camera’s features – the view screen that can be used as a light table, the possibility of deleting sub-par images. On top of that, using the electronic flash in this particular site of analogue creation – which normally had to be protected from interference by light infiltration – something about it, without my deliberately evoking it, was provocative and sacrilegious.

At first, I didn’t have a very clear idea of the real extent of obsolescence of darkrooms and analogue photography. When I started this project, which for me is as much a visual inquiry as a tribute to the photographer’s trade, on a place that is so powerfully “photogenic” because it is marked by manual labour and the patina of time, I quickly realized that a certain kind of photography was in decline.

As I was working, I rediscovered, as a sort of anthropologist, both a known territory and a world that belonged directly to the world of photographic technology. I should add that there was a good opportunity to breathe a little irony into the project. Despite the loud protests of those who are utterly devoted to the old processes, there’s no question that digital tools are a spectacular advance. Through my professional network, I inventoried and photographed more than a hundred darkrooms, and this gave rise to a first series.2 Then, I wanted to go and see what darkrooms looked like elsewhere, to study how they were different from ours, and so I photographed them in Havana, Toronto, Niamey, Berlin, Ho Chi Minh City, Mexico City, Brussels, and Paris.

The aesthetic that I set up resembled that of an insurance claims adjuster taking pictures of an accident site.

RB: At first glance, your view of darkrooms does seem anthropological; however, it quickly becomes obvious that your eye is drawn to things seen from very close up. Why this choice of playing on fragment, detail, colour, and objects as objects ?

MC: I produced the first cycle very quickly and mainly in the Montreal region. The interest that British photographer and publisher Martin Parr showed at this point in the controversial and aesthetic qualities of my work did not encourage me to take a critical step back. I think that as a photographer I’m motivated by aesthetic requirements, and my framings constantly exert a tension between the subject and what is out of frame. That is why general angles of darkrooms weren’t interesting to me.

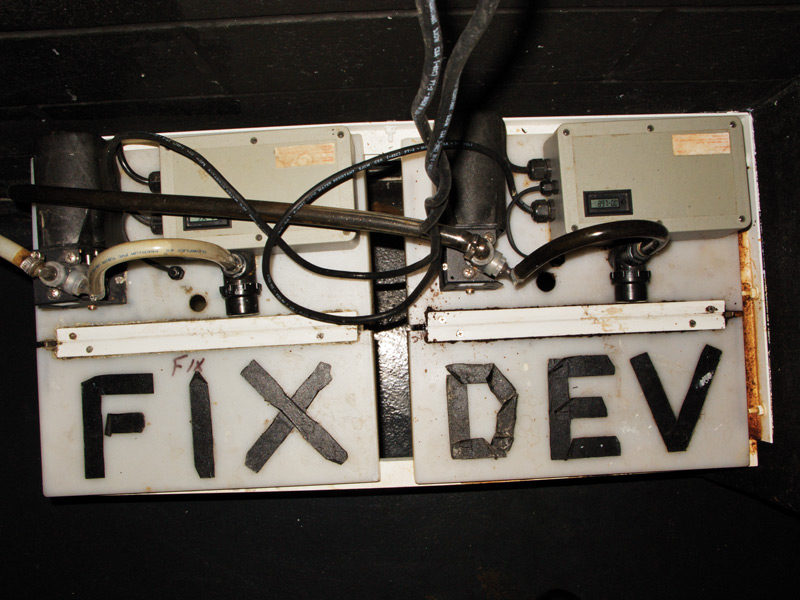

By the time I did the second cycle, the digital cameras that I was using were improved and the angle of field of lenses had increased. It may also be that in privileging close-up images, I wanted to put the architectural and mechanical diversity of the darkrooms I visited into sharper focus. But the colour and the electronic flash are, I think, the most meaningful vectors in this documentation of darkrooms. What I wanted to show with the colour and light, through this succession of close-ups that seem formalist and abstract, fundamentally has to do with the traces of manual labour, toil, and repeated gestures.

One of the criticisms of the series is that I focused on the dilapidation and decrepitude of the places I photographed. I don’t see things this way; a very large part of the history of photography took place in similar places, and not in antiseptic digital laboratories.

RB: These places seem abandoned, but what is also striking is the handiwork aspect of what we are shown. Are photographers tinkerers by nature, and, in the end, isn’t photography essentially a vast tinkering with reality ?

MC: One might indeed presume that the darkrooms are abandoned because I made the choice, from the beginning, to show them as “still lifes.” The aesthetic that I set up resembled that of an insurance claims adjuster taking pictures of an accident site. But most of the darkrooms that I photographed are still accessible and functional. That said, and in relation to the nature of the work done in the darkroom, it is impossible to avoid wear and disrepair, considering that chemical substances are constantly splashing from the baths, dripping from our hands, and spreading on the floors and walls and all around.

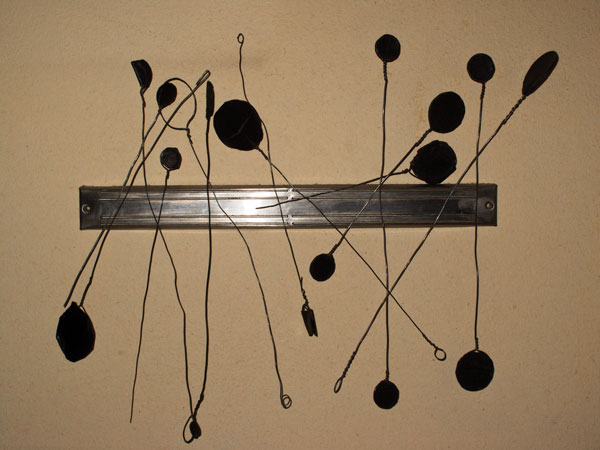

With regard to tinkering, I was surprised to discover the odds and ends of plumbing and electricity. I saw a great deal of resourcefulness among the portrait makers of Niamey, who, given their limited financial means, jerry-rigged their inactinic lights with plastic bags, paper, and paint. In a way, my work is a tribute to the inventiveness of the people who craft darkrooms.

As for tinkering with reality, my relationship with photography is more on the order of hand-to-hand combat with the materiality of things. I rejoice in the formidable paradoxical power of photography to embellish ruins, to create “beauty.” That said, any reference to painting that may be associated with my work is not a goal in itself. It is part of the variations and visual vocabulary of photography, and I have learned to be suspicious of its seductive power. In fact, my relationship with photographic creativity is exploratory and instinctive.

RB: Your work on darkrooms has been published in the United States. For a Canadian artist or a Quebec artist, this is a major success and definite recognition. How did this book come into being, and what has it meant for your subsequent work ?

MC: The monograph titled Darkroom was published in 2007 at the instigation of Martin Parr, who was co-editor of a series of books for Nazraeli Press (Portland, Oregon). In fact, it was through the photographer Donigan Cumming that early images from the darkroom project were presented to Parr, who was on the lookout for unusual photographic pieces. The book provided real impetus for my work on darkrooms, and things haven’t slowed down since. The reaction made me realize that this work is paralleling a historic upheaval: the transition to digital tools – a transition that is also forcing us to think differently about images.

RB: In the summer of 2010, this project was one of the highlight exhibitions at the Rencontres internationales de la photographie d’Arles (France). As we know, Arles is an international crossroads of photography. How as your work received there ?

MC: First, there was the undeniable enthusiasm of François Hébel, the director of the Rencontres d’Arles, who has been wanting to present my works for several years. He and his team showed great sensitivity and coherence in the selection and hanging of pieces, as well as in the video shown during the event.

My work was received very positively, and this bodes well for its continued exhibition in Europe. I’m working on this, in collaboration with Galerie Simon Blais.

RB: What is going on now with your work on darkrooms ?

MC: By the time this interview is published, I will have begun what I consider to be the third cycle of this body of work, which will involve some new aesthetic concerns, notably on the materiality of photographic archives and the storage of analogue cameras. The cycle will start with a trip to Tokyo during which I will find out about Japanese photography; it seems that analogue tools are still being used widely in Japan.

Continuing with the darkroom project is thus a central concern for me, along with the planned publication of a new monograph that will synthesize the body of images and integrate other work around the idea of the decline of analogue photography. In organizing the images for the book, I try to reconstruct my own experience with the darkroom, the feelings I had when I worked in it, and evoke an inventory of places in a syncopated path. I will be visible between the lines, so to speak, but it is also the history of this emblematic and long-essential site of photographic practice. I try absolutely, in comparison to my previous autobiographical work, to keep my introspective passions at bay. In a way, I have reversed the perspective: before, I worked in the darkroom, and now the darkroom serves as my model and creative pretext.

Translated by Käthe Roth

1 See Michel Campeau, Territoires: photographies 2001-2004 (Montreal: Les 400 coups, 2007).

2 Series presented in 2008 in the group exhibition “New Typologies” during the first edition of the New York Photo Festival.

Michel Campeau, who has been a contemporary-art photographer for four decades, has received the Duke and Duchess of York Prize (2010), the Jean-Paul-Riopelle Career Grant (2009), and the Higashikawa International Photography Prize in Japan (1994). His work, which explores the subjective and narrative dimensions of images, questions the conventions of documentary photography. A retrospective exhibition of his work in 1996 at the Canadian Contemporary Photography Museum covered his production from 1971 to 1996. Campeau is represented by Galerie Simon Blais (Montreal), and lives and works in Montreal.

Richard Baillargeon is an anthropologist by training, and he pursues a photographic practice based on the encounter of image and text. He was an active participant in the foundation of VU, centre de diffusion et de production de la photographie, in Quebec City. From 1989 to 1994, he was director of the photography pro- gram at the Banff Centre for the Arts in Alberta, and he was artistic director of the Centre de sculpture Est-Nord-Est in Saint-Jean-Port-Joli, Quebec, from 1995 to 1997. Currently, he is a professor at the School of Visual Arts at Université Laval.