By Érika Nimis

In June 2017, Le Mois de la Photo de Montréal metamorphosed to the Biennale de l’image, taking on the name MOMENTA, plural of momentum, which means “impetus, energy, force, thrust, drive, impulse”1 and often denotes a favourable or propitious situation. Would the update to this international event devoted to the contemporary fixed and moving image be successful and yet provide continuity with the old formula? The theme concocted by the “guest curator,” teacher and art critic Ami Barak, for the 2017 edition was “What does the image stand for?” Although it may seem a little odd, this phrasing has been around in various forms for a few years now.2 According to Barak, “What does X stand for?” is the translation of a paraphrased quotation by psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan, “De quoi l’objet a est-il le nom ?” Taking a closer look at Lacan and his “objet a,” we find that it “is not a mere theoretical concept like any other. What makes it unique is that it is an object deprived of any kind of logic of a mathematical order”3 and is related mainly to the notion of desire – a subject that was at the heart of the artists’ roundtable, titled “Sujets a: desire – appeals,” organized at the Canadian Centre for Architecture on September 9, 2017. This question is, again according to Barak, the result of a persistent “misunderstanding” that the photographic image faithfully reproduces reality and acts as “evidence.” In reality, Barak reminds us, there is no such thing! MOMENTA’s mission was thus clear: make this warning, often ignored by common sense (as proved by the unflagging success of the World Press Photo annual exhibition), available through as many artworks, recent or not,4 as possible.

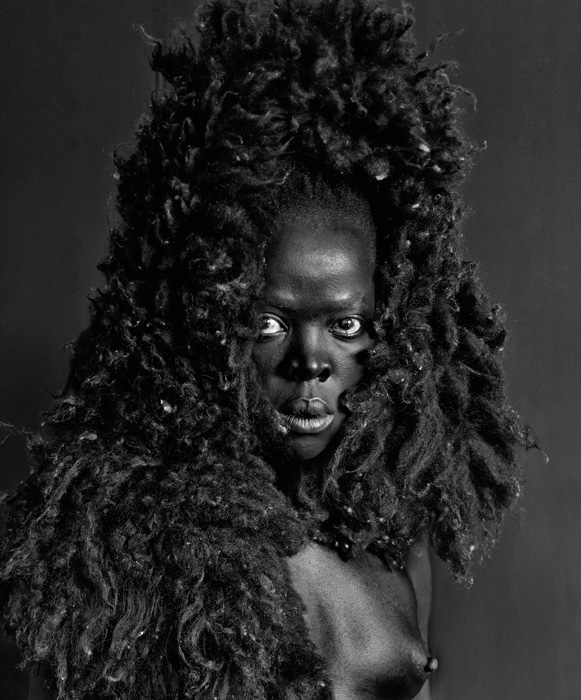

What does the MOMENTA biennale stand for? Appealing to our numbers-conscious era, the biennale’s media package emphasized that no fewer than thirty-eight artists from seventeen countries were being presented in twenty-one locations: twenty-three artists in the central exhibition displayed in two locations, the Galerie de l’UQAM and Centre Vox; fourteen solo shows in the usual partner venues such as the McCord Museum, the Museum of Fine Arts, the Maison de la culture Frontenac, and several other galleries and artist‑run centres; for the first time, the Musée d’Art Contemporain joined the biennale with the headline exhibition by Taryn Simon; there were also a documentary section at Artexte and other satellite exhibitions. All of this was intended to give even more volume and visibility to the event, the two posters for which advertised a deliberately consensual and engaged tone. The image on the first was Phoebe, the portrait of an androgynous, trans Amy Winehouse, taken from Mexican photographer Luis Arturo Aguirre’s series Desvestidas (2011). On the second was a self-portrait by South African artist Zanele Muholi, taken from her series Somnyama Ngonyama (2015), presented at Centre Clark; this image was also used for the cover of the catalogue (which was restrained in design and published by Kerber Verlag). The question of an undefined identity – or, rather, one that is defined in the margins – was core to this first edition of MOMENTA, which gave pride of place in its program to artists who were non-Western (including, notably, four African artists), Métis, and First Nations, including Canadian stars Terrance Houle, Nadia Myre, and Meryl McMaster.

Constraints, mainly budgetary ones, for an event whose name would lead one to believe that its eyes are bigger than its stomach led the organization to charge admission – coyly called a “passport” – to the central exhibition, for the first time in thirty years (if I’m not mistaken). In an irony of scheduling, another photography event was taking place in Montreal at the same time, with major media coverage, in a smaller and jam-packed venue in Old Montreal: the exhibition of winners of the World Press Photo awards for 2017. The price of entry, the same as that for the MOMENTA central exhibition, was no deterrent: visitors/voyeurs came in droves (a surprise, actually, in this era of “whatever” on social networks5) to reflect before life’s tragedies, aestheticized by masterful framing, spread out on panels like pieces of truth, evidence by image, that the world continues to take a turn for the worse. So, rather than insisting on MOMENTA’s few misses, let us celebrate the fact that Montreal is still hosting an event that aspires to offer visibility to artists who reflect on the status of the image in “societies of the spectacle” that are drowning in “fake news.”

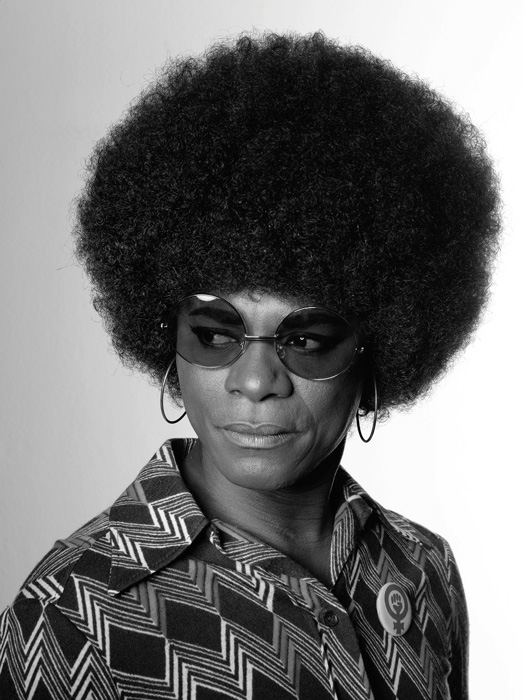

At Centre VOX, the first section of the central exhibition, was a grouping of works – not all of them recent – each of which, in its own way, tried to respond to the thematic question. The show opened on a self-portrait of Samuel Fosso in the character of American activist Angela Davis, taken from his now-famous series African Spirits (2008). Echoing the leitmotiv explicitly stated on the two MOMENTA posters, the images twist rather than reveal reality, and it is this fertile twist that is thought provoking. Although the links among the works presented were obvious, the few images displayed (one, two, or three) per artist gave the unfulfilling feeling of a snack rather than a full meal, what with the noisy distraction of the video installations that suddenly seemed more consistent than the still images. For instance, Montreal artist Pascal Grandmaison, in The Neutrality Escape (2008), paid tribute in video to the 16 mm Éclair NPR camera with which documentary filmmaker Michel Brault had worked, lovingly filmed here in macro and with a very shallow depth of field, as if the artist wanted to capture each grain of the surface of this travel-ready camera that had revolutionized cinéma vérité. A similarly unexpected organic side of the machine was found in the work of Australian Joshua Petherick (who was also repre- sented at UQAM with a minimal installation of “bag images” called Carriers), who had digitally recorded the interior of a scanner with a cell phone and showed the result on three screens, like digital aquariums, set at knee level.

From the digital to the gelatin silver, the materiality of the image and the apparatuses that produce it were also celebrated at Galerie Dazibao, with Karam Zaatari’s multimedia installation Letter to a Refusing Pilot, first presented in the Lebanese pavilion at the 2013 Venice Biennale. Zaatari is known mainly for his formidable artistic and archival work at the Arab Image Foundation in Beirut,6 nourished by his intimate war-troubled memories of Lebanon that reopen tormented pages of history. Taking the archives out of the box, bringing them alive again – that is his project. The central piece in Letter to a Refusing Pilot is a thirty-minute fiction film, laden with references, that relates a dramatic episode in Zaatari’s adolescence. He was living in Saida, a town in southern Lebanon that was bombed by the Israeli air force in June 1982; this tragic episode was sublimated by a gesture of resistance by an Israeli fighter pilot who decided to drop his bombs into the sea rather than destroy the high school in Zaatari’s neighbourhood. Zaatari wanted to pay tribute to this gesture, left out of history books, by “replaying” the bombardment through “evidence,” personal archives, aural and visual, which he filmed in a calm, gentle way, like an archivist handling pieces of the past with care and detachment. At one moment, he takes off his gloves and with a finger touches the places where his neighbourhood school was finally hit by bombs, causing its destruction; through digital effects he re-creates the explosions, which spring up from his finger on the archival photograph. The sound track, on which we hear a song by Françoise Hardy, “Comment te dire adieu” (1968), is just as important as the image. It dramatizes the film, cradles it, as does the purring of an old Eiki Slim Line projector (format 16 mm) that shows a parade of colour images of bombardments on an opposing screen, in front of a red-velvet seat, a survivor of a movie house.

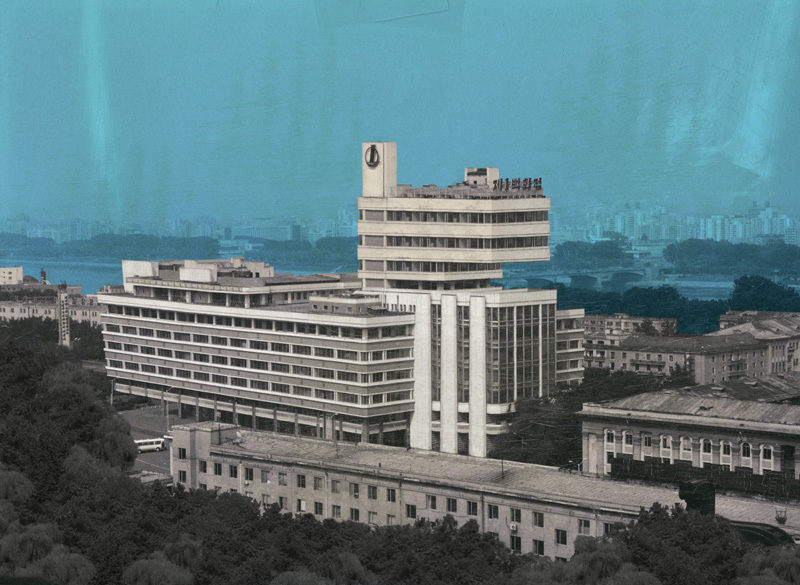

The question of diverted archives that end up saying much more than the history that they bear witness to as documents was central to other works in MOMENTA. The diptychs by South Korean Seung Woo Back, presented at the Galerie de l’UQAM, juxtaposed enlarged, coloured, and modified versions of 1950s postcards of similar places in both Koreas. In Hands-me-Downs (2011), Yto Barrada revisits a page in Morocco’s history, starting from a montage of Super 8 family films, accompanied by a completely fictional narrative that yet contains unsettling truths.

Using a detail so innocuous that it passes unseen to reconstruct a political story of capitalism since the end of the Second World War was the program of American artist Taryn Simon in her installation Paperwork and the Will of Capital at the MAC. Supported by the Gagosian Gallery, Simon did not skimp on the means used to meticulously re-create and subtly photograph the “impossible bouquets” that sat on the official tables at which the accords and treaties that rule our world were signed. To quote the well-written text of the press release, “By pairing her own photographs of the reconstructed floral arrangements with texts describing the individual accords, Simon’s work examines how the stagecraft of power is created, performed, marketed, and maintained.”7

Finally, I’ll mention some artists who tried to stir up the studious ambience of this MOMENTA, such as Serbian artist Boris Mitic´, whose Museum of nothing(s) (2017) offers a sort of filmic encyclopedia on the concept of nothing, the result of an anonymous collaboration among sixty budding and established filmmakers around the world. Another light moment was the scene of snow removal on a Montreal street, from a nineteenth-century photograph from the William Notman collection on loan from the McCord Museum, revisited in a sound installation by Frédéric Lavoie. In the end, all of the works presented at MOMENTA had something to reveal about the relationship, not always healthy, that we maintain with images, echoing very contemporary explorations. This was true even of the antiquated-looking videos by Mircea Cantor: a circle of virginal young women sweeping, in cadence, a stretch of white sand, a metaphor for the very common melancholy that we all feel at some time or another – that need to “disappear from ourselves.”8

Before erasing everything from our memories, this 2017 edition appears, looking back, to have been a more-than-honourable attempt (given the budgetary and political constraints). But it was far from exciting; rather, it was like a good student, making no waves (due to wanting to do too well). It had a sense of déjà vu, a sensible compromise between some “sure values,” stars of the art market, and less-well-known artists, from worlds that are more demanding, even hermetic. I would wrap up with a question that some might find naïve. What if this lacklustre review caused the organizers to rethink this international-scale Montreal event differently? Why not try to use more-local resources to initiate an anti-conformist biennale of the image that would rub the art world and its market the wrong way? Is this even possible?

Translated by Käthe Roth

1 en.oxforddictionaries.com/thesaurus/momentum.

2 For instance, I heard and read the French-language version of the expression in three different contexts during the few days when I was writing this review.

3 Mathieu Blesson, “De quoi l’objet a est-il le nom ?,” Psychanalyse 29, no. 1 (2014), English-language abstract, www.cairn.info/revuepsychanalyse-2014-1-p-35.htm.

4 Budget cuts have had visible effects on the biennale; for example, the organization selected works that had already “made an appearance” at other biennales, galleries, and international venues. To my knowledge, only Boris Mitić’s film was commissioned by MOMENTA, with the Biennale de l’Image en Mouvement in Geneva as co-producer.

5 One has only to think of the recent scandals in the press-photography world, such as that of the war photographer whose work was published in very reputable news outlets . . . until he was discovered to be fictional; someone had been surfing the web, appropriating other photographers’ pictures, and publishing them under a false name. See Thierry Secrétan’s blog entry, “DON MCCULLIN HELP US! Here Comes the Age of the Fake War Photographer,” September 22, 2017, imatag.com/ blog/en/2017/09/22/don-mccullin-help-us-here-comes-the-age-of-the-fake-war-photographer/.

6 Zaatari’s work was recently presented in an exhibition titled Against Photography: An Annotated History of the Arab Image Foundation at the Museu d’Art Contemporani in Barcelona. See macba.cat/en/exhibition-akram-zaatari/1/exhibitions/ expo.

7 macm.org/en/press-release/taryn-simon-at-the-mac/.

8 The title of an essay by David Le Breton, Disparaître de soi (Paris: Éditions Métailié, 2015) (our translation).

Erika Nimis is a photographer (former student at the photography school in Arles, France), Africa historian, and associate professor in the art history department at the Université du Québec à Montréal. She is the author of three books on the history of photography in West Africa (including one drawn from her doctoral dissertation: Photographes d’Afrique de l’Ouest. L’expérience yoruba [Paris: Karthala, 2005]). She contributes to a number of magazines and founded, with Marian Nur Goni, a blog devoted to photography in Africa: fotota.hypotheses.org/.