By Pierre Dessureault

It seems less and less possible to analyze photography and photographic history without talking about production protocols, dissemination strategies, and contexts for conservation and display in public collections. Andrea Kunard situates her undertaking in regard to this position from the start:1 “Inasmuch as a presentation of selected works highlights certain objects, so it states something about the institutional and cultural history and the values embedded in the activity of collecting. Museum collections are generally multifaceted entities that reflect the concerns of numerous individuals (curators, directors and donors), often over long periods of time.”2

The history that structures Kunard’s project, discussed in detail in the catalogue accompanying the exhibition, is not linear and complete, nor is the aim to highlight all the major art currents and aesthetic categories that have marked the evolution of the medium over four decades. Rather, Kunard sets out to trace how photography has been conceived at certain times, and how these conceptions were implemented by the National Gallery of Canada and the Canadian Museum of Contemporary Photography (CMCP) to assemble two collections and build a patrimony that, today, we can situate within the evolution of cultural practices that marked an era.

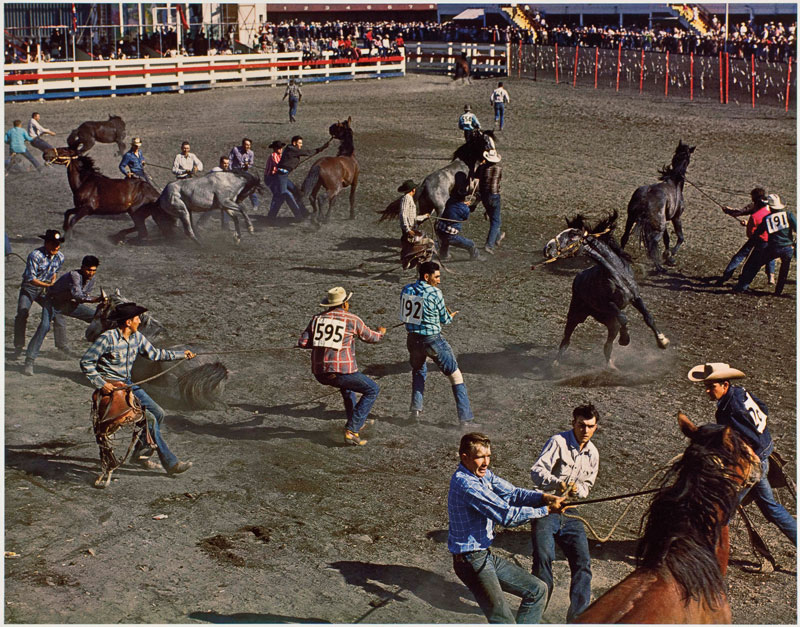

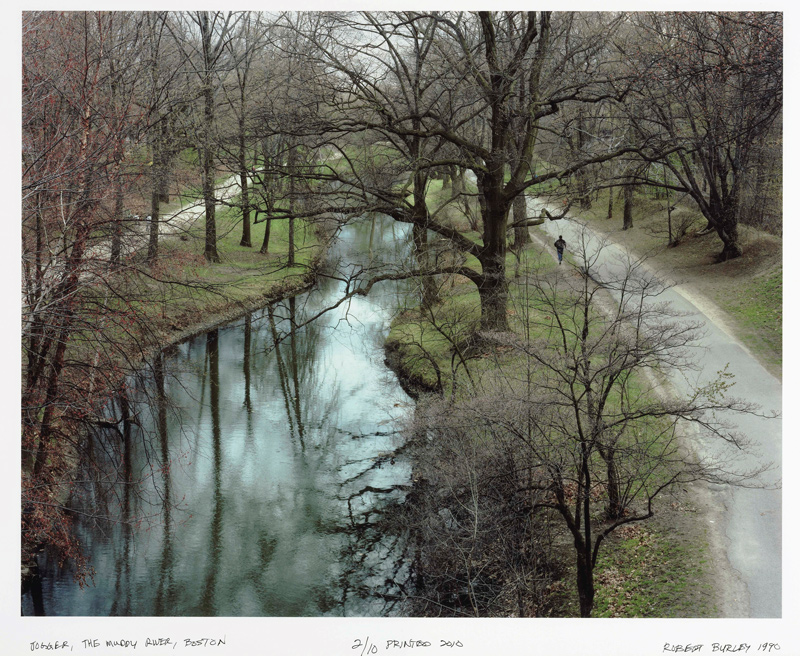

The decades covered in the exhibition correspond to a particular period in the development of the medium both in Canada and abroad. The 1960s3 and ensuing decades were marked both by the ascent of photography to the status of art – with all the ambiguities and arguments that a debate inherited from the nineteenth century involves – and by recognition of the plurality of photographic practices that are inscribed in the broad field of image-based production. It was a transition from photography bound to description of the real and aesthetic codes inherited from the avant-gardes of the 1920s and the pure photography of the 1930s to 1950s to a proliferation of approaches, a diversification of protocols and image-production codes, and a blurring of lines between the canonical genres that had been in force. The new era was one of a search for new forms for expression, unusual narrative strategies, and innovative visual vocabularies that would be used to look at previously unexplored subjects.

This period of innovation corresponded to institutionalization of the medium. Although photography had been integrated into the activities of the National Gallery of Canada and the Still Photography Division of the National Film Board (the ancestor of the Canadian Museum of Contemporary Photography) for several decades, the late 1960s saw the recognition by the Treasury Board of three complementary national collections representing “three points of view on photographic history: Canadian documentation and photographic records at the Archives; the international history of photography as a fine art at the National Gallery; the representation of aesthetic and social movements in contemporary Canadian photography at the NFB Still Photography Division.”4

The National Gallery of Canada’s photography collection, created in 1967, is related to a historical and international vision of “photography as art.” In the view of its founder, James Borcoman,

Photography is the visual memory of humankind, a storehouse of information, and a witness to things that no one has ever seen or will see directly. Photographs can reflect the world, or they can reveal the photographer. More disturbing, they can reveal ourselves to ourselves. The photograph is a model for a point in time that has been selected, crystallized, and held out to us for contemplation. The ambivalent relationships that exist in a photograph between different realities – the reality of the physical world, objective reality and subjective reality, fact and fiction – stimulate, intrigue, and demand that we con- front the meaning of the world in which we live. In its final challenge, the photograph forces us to take the spiritual measure of fact.5

This approach was in step with the ideas of the time on the visual specificity of the photograph, which, even if it claimed a place in the field of fine art as an expression of a personal vision of the world, tended to affirm its nature as a product of mechanical and physiochemical processes. This vision found its most complete expression in the writings of historian of photography Beaumont Newhall; similarly, in Borcoman’s view, the commonality of photographic styles that have succeeded each other through history is “the direct use of the camera for what it can do best, and that is the revelation, interpretation, and discovery of the world and nature. The greatest challenge to the photographer is to express the inner significance through the outward form.”6

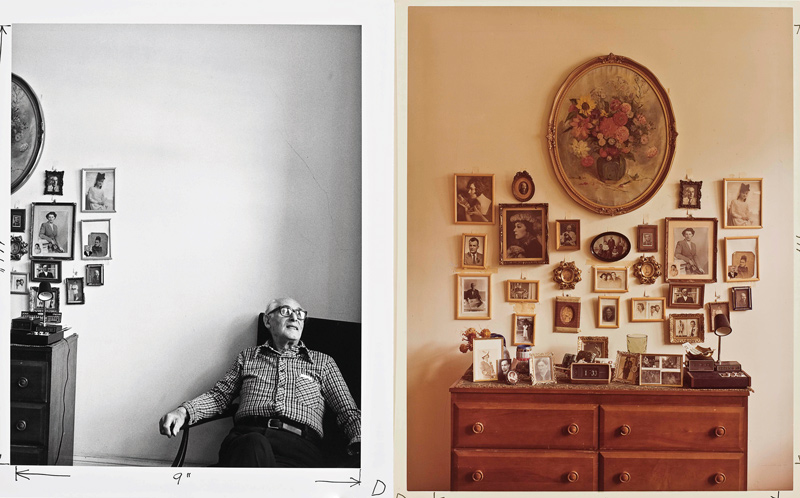

Given this essentialist perspective of the image as aesthetic object, the National Gallery of Canada collection was developed with an emphasis on amassing significant groupings of an individual’s production or revealing an era or a movement, rather than on acquiring the unique emblematic masterpiece that has inflected the course of the history of the discipline, as is done with fine art. This way of doing things, which in a way parallels the medium’s mode of production – that of proliferation – was, beyond simply conserving these groupings, to provide the basis for studies on them and their historical resonances in the development of practices: “Where one or two photographs will tell us little of the photographer’s vocabulary and interests, a quantity will open the door to understanding.”7

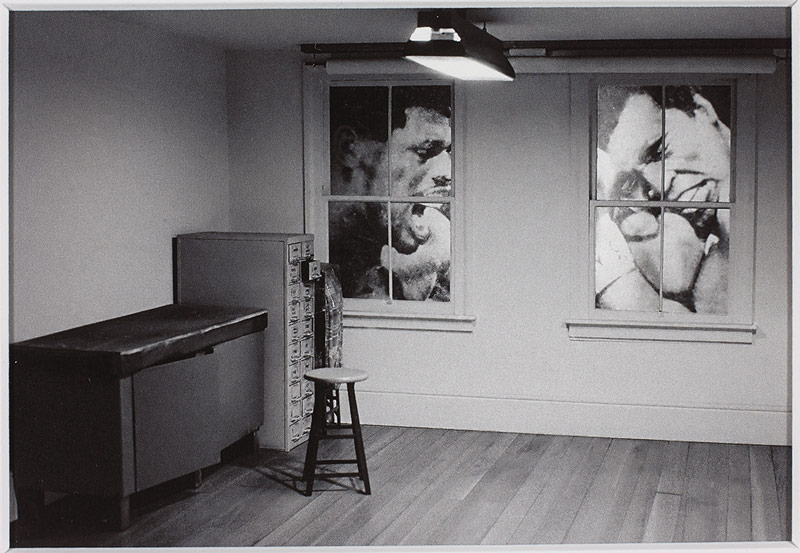

Although the Gallery intended to assemble large bodies of work, the fundamental unit upon which each ensemble was based was the exceptional print in which the unique characteristics of the medium are tangibly embodied and viewers may appreciate “the sensuous pleasures of line and tone which are so closely bound up with the expressive potential of the original print – the print that comes out of the photographer’s darkroom, the print that is the product of the photographer’s hand working in consort with his eye and his mind.”8 Given the collection’s historical and international mandate, Canadian contemporary production was represented in sufficient proportions that it could be measured against the best international work and be seen as in step with the major trends of the time. The Gallery’s contemporary-art department also collected, with a completely different perspective, work by contemporary Canadian artists who used the medium as a material capable of structuring ideas and as a vehicle for challenging the nature of the artwork and its protocols of production. Two contexts, those of art photography and contemporary art, conferred legitimacy upon the medium by acknowledging its specific status and distinct position in the world of images.

Whereas the Gallery’s photography collection followed a linear trajectory of development, framed by the institution’s rigorous museum practices, the path of the NFB’s Still Photography Division was bumpier. Formed to be the production unit and image bank for government information within the NFB, and given the mission of creating and disseminating an institutional vision of the nation and its progress, the Service reinvented itself and metamorphosed over the four decades covered in the exhibition. What did not change was its area of activity: current Canadian photography.9

We must therefore distinguish within the collection – in its current state – between the archival collection composed of commissioned works produced starting in 1962 in response to the Service’s mandate as official photography department of the Canadian government and the collection of aesthetic photography created, as the Gallery’s was in the late 1960s, with the intention of acquiring, solely for their photographic qualities, the works of a rising generation of photographers who displayed their personal visions independent of nationalist themes favoured up to then. The borders between the two entities were porous, and a number of images from the past, defined originally by their subject and informational characteristics, were to be re-examined over the years, judged from the point of view of their distinctive visual qualities, and highlighted in the aesthetic photography collection.

During the period from 1960 to 1984, the Service was positioned as a disseminator of the multiple points of view on photography and its plurality of practices through exhibitions first presented at the Photo Gallery, inaugurated in 1967, and then touring the country, as well as an ambitious publication program, also launched in 1967.

In contrast to the rigid protocols of a museum collection, “Under the NFB, the institution’s area of concentration could be best described as the ‘here and now.’”10 The Service took drastic action with regard to photographic production of the time: it acquired groupings that it deemed representative and structured them to highlight their coherence and relevance, both in Canadian photography as a whole and in the evolution of individuals’ practices. For the Service, production, acquisition, and dissemination were inseparable and represented three stages of a continuum. Innovation and experimentation served as justification for eclecticism in the collecting policy, which stood in for critical discourse and allowed deliberately antagonistic practices to coexist.

In 1983, the NFB board of directors adopted guideline principles for the Service that clarified and framed its mission and methods; although they had evolved over the years, the ultimate goal was still to conserve, interpret, and disseminate contemporary Canadian photography, both documentary and artistic. The creation of the CMCP in January 1985 and its affiliation with the Gallery confirmed this mandate; the new institution’s activities were regularized and brought into line with museum practices. Two books describe the path of the image bank in the museum collection and testify to the diversity of production conserved by the Service and its successor. Contemporary Canadian Photography from the Collection of the National Film Board11 relates the development of the Service from its creation, in 1941, to 1984, when the first chapter of its history ended. Beau12 celebrates the arrival of the CMCP in its new quarters at 1 Rideau Canal and presents acquisitions for the museum’s collection between 1984 and 1992, during which time the new institution consolidated its position in the landscape of museums through its program of touring exhibitions that travelled around the country, earning it the nickname “museum in boxes.”

Given these publications and the provenance of the great majority of works presented in the exhibition or amply commented upon in the accompanying catalogue, it is clear that the collection of the now-defunct CMCP, transferred in 2009 to the Gallery, remains the collection of reference for the evolution of Canadian photography between 1960 and 2000. The catalogue captions clearly indicate the double provenance of the images reproduced – Collection of the CMCP, National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa – and it is curious that the provenance of the photographs presented in the exhibition is not mentioned. Photographs, just like artworks, are inscribed in the history of their provenance; their life is defined by the successive contexts into which they were integrated, including those of collections. And a collection is built in a deliberate process, a systematic approach oriented by operational protocols, ideas, and a conception of its objective – in this case, contemporary Canadian photography. The combination of these parameters imposes logic on the collection and affirms its unique personality.

Another chapter in the history of Canadian photography has opened with the recent creation of the Canadian Photography Institute of the National Gallery of Canada, which brings these two highly complex collections, with identities firmly planted in parallel paths, under shared management. The collections, like the images, are creations inscribed in the course of values of the time and subject to an uninterrupted series of critical examinations that are redefining the territories that they occupy in Canadian culture.

Translated by Käthe Roth

2 Andrea Kunard, Photography in Canada 1960–2000 (Ottawa: Canadian Institute of Photography of the National Gallery of Canada, 2017), 11.

3 See Pierre Dessureault, “La question de la photographie,” in Denise Leclerc and Pierre Dessureault, Les années 60 au Canada (Ottawa: Musée des beaux-arts du Canada and Musée canadien de la photographie contemporaine, 2005), 114–65. Also available as The 60s in Canada (Ottawa National Gallery of Canada, 2005).

4 Martha Langford, “The Canadian Museum of Contemporary Photography,” History of Photography 20, no. 2 (Summer 1996): 175; see also James Borcoman, Magicians of Light: Photographs from the Collection of the National Gallery of Canada (Ottawa: National Gallery of Canada, 1993), 13; Ann Thomas, “The National Gallery of Canada.” History of Photography 20, no. 2 (Summer 1996): 171–74.

5 Borcoman, Magicians of Light, 12.

6 Beaumont Newhall, The History of Photography, 1839 to the Present (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1964), 201.

7 Borcoman, Magicians of Light, 13.

8 James Borcoman, introduction to the catalogue accompanying the exhibition Photography in the Twentieth Century (Rochester, NY: George Eastman House, 1967), quoted in Kunard, Photography in Canada, 14.

9 I cannot ignore here my point of view of a privileged observer and my position as stakeholder during my years at the NFB’s Still Photography Division from 1971 to 1984 and then at the CMCP from 1985 to 2007.

10 Langford, “Canadian Museum,” 177.

11 Pierre Dessureault, Martha Hanna, and Martha Langford (eds.), Contemporary Canadian Photography from the Collection of the National Film Board (Edmonton: Hurtig Publishers, 1984).

12 Martha Langford, Beau (Ottawa, Canadian Museum of Contemporary Photography, 1992).

[Full issue available here : Ciel variable 108 – GOING PUBLIC ]