[Spring-Summer 2018]

By Claudia Polledri

According to Lebanese artist Akram Zaatari, photography is expressed in many ways. This is the message of his most recent exhibition, Against Photography: An Annotated History of the Arab Image Foundation, a kaleidoscopic journey, through stories and images, into the archives of the Arab Image Foundation, an institution with which he has profound connections. Here, he proposes to retrace the history of the foundation, documented and paraphrased from his viewpoint as an artist. Presented from July to September 2017 at the Barcelona Museum of Contemporary Art and from November 2017 to February 2018 at K21 in Düsseldorf, Against Photography will make its final stop in spring 2018 at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in Seoul, South Korea.

The Arab Image Foundation. 1997–2017: It has been twenty years since the Arab Image Foundation (AIF) was founded. Established in Beirut, in a country still in the process of reconstruction after a long civil war (1975–90), the AIF is the successful response of a group of artists – Akram Zaatari, Fouad Elkoury, and Samer Mohdad – to the absence of institutions in the region devoted to the conservation and dissemination of the cultural heritage. Directed by Marc Mouarkech and by Clémence Cottard Hachem, the director of collections, today the AIF has about six hundred thousand pictures, most of them taken in the Maghreb and the Middle East (Lebanon, Syria, Palestine, Jordon, Egypt, Iran, Iraq, Morocco). It is in fact through the illustration of the geographic roots of the AIF that the journey begins; it is a way of enabling visitors to situate the provenance of the collections, but it also indicates the relationship between image and territory as being one of the underlying themes of this visual trajectory. Since its foundation, the AIF has constantly evolved not only through acquisitions, but also through the conservation and digitization of its photographic collection and activities to highlight it. The fifteen exhibitions produced over these years provide a clear example of this. After participating in its foundation and producing many of these exhibitions, today Zaatari continues his collaboration with the AIF through his art practice and remains no doubt one of those most familiar with its photographic heritage.

To see this exhibition solely as a depiction of the history of the AIF would, however, not take its full scope into account. Nor is it simply a retrospective of Zaatari’s work, even though the works on display cover a fairly wide period of his production. Rather, it is the overlapping of his two careers, one institutional and the other artistic, that makes this show so rich and stimulating, from the point of view of both the artworks on display and the research undertaken by Zaatari in the foundation’s archives. But what makes it even more captivating is the variety of treatments to which Zaatari submits photographic objects in order to highlight their documentary and aesthetic potential, as well as his technique and the assorted uses and experiments to which it may be subjected. In short, it is a true reflection in images that Zaatari proposes, a discourse on photography, which, he explains, “figures not only as a medium, but also as a subject.” It is a subject, I might add, that is also clearly situated. Indeed, whether it is considered according to his technical variations – from calotype to gelatine silver to digital – or his social practice, his relationship with the sites and events that took place in them has clearly had a central role. What emerge are rich and stratified images, in which the history of photography, placed in the foreground, is in constant dialogue with the history of the region. Three major axes were the object of Zaatari’s visual reflection: the collections, photography studios, and photographic technique. They are articulated in a strongly coherent exhibition that makes no moral judgments.

“I define my work mainly as that of collecting.” How can the full extent of a archive as vast as the AIF’s be encompassed? How can its collections be presented in public, and how can they be described? In the first gallery, The Book of All Collections (2017) is the result of Zaatari’s proposal to retrace the history of the AIF’s collection practices and to provide access to the content of three hundred collections. To do this, he dug into the foundation’s archives to consult institutional files, biographies, acquisition notes, research reports, and more. He pursues this major documentary project in the other galleries by implementing different approaches focused directly on the images.

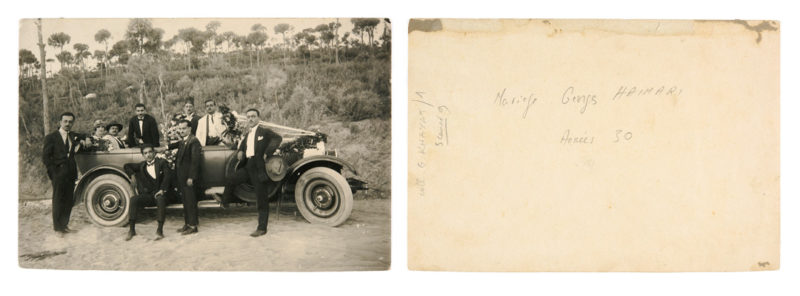

A similar methodology – the creation of series of images around a topic that has appeared recurrently, independent of the provenance or dates of these shots – was adopted for a number of the AIF’s exhibitions. Two stand out in this respect: The Vehicle (2017), a partial reprise of the exhibition The Vehicle: Picturing Moments of Transition in a Modernizing Society (1999), and Men Posing While Crossing Ain el Helweh Bridge (2007), the images for which are taken from the collection of Lebanese photographer Haschem el Madani. Visual expressions of the changes in a society with the advent of modernity, the vernacular photographs in these exhibitions are characterized by the central role accorded to representations of the automobile. Whether placed in the foreground in family portraits – the father proudly at the wheel, the mother and children in the back seat (1920, collection of Tania Balkalian) – or used as set dressing for festive events (The Wedding of George Haimari, Lebanon, 1930, collection of George Khayat), cars are the true subject of this series, which also offers valuable clues to clothing of the era. In addition, Zaatari’s choice to display the recto and verso of images expands the documentary range of the photographs by showing the wealth of information given on their backs (possible inscriptions, dates, language, place, presence of stamps, and more). The series of portraits taken in Ain el Hilweh, near Saida (or Sidon), Lebanon, of young people crossing the bridge on foot, in cars, or on bikes similarly constitute a significant window onto the society of the time, as well as a symbol of developing modernity. Produced following the same methodological principle of the recurrent element, the series A Photographer’s Shadow (2017) focuses on another, more strictly “photographic” element: the presence in the image of an element normally considered accidental: the photographer’s shadow. Without limiting himself to its banal-looking aspect, Zaatari dwells on this visual intrusion in which he sees an “agent of connection” that makes visible the relationship between the image and its author.

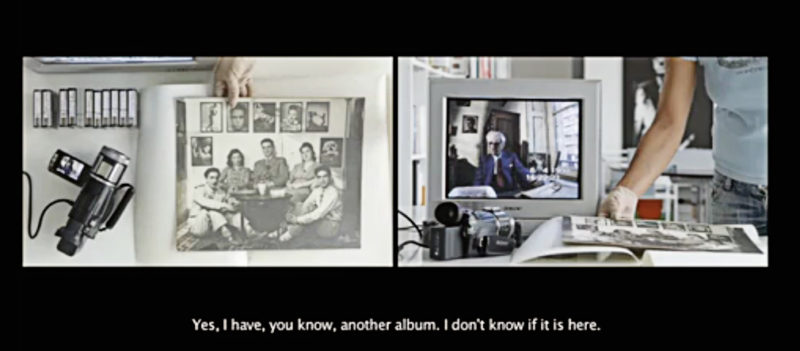

Although mediated by the filmic apparatus, the relationship with the collections that imbues the two-channel video On Photography, People and Modern Times (2010, 38 min.) is just as interesting. In this case, the camera operates as the “liaison agent” by establishing a relationship between the private dimension of pictures – their intimate existence in family albums and memories in the guise of captions – on the one hand, and the public status that they obtained once acquired by the foundation, on the other. The link that Zaatari creates between these two statuses through the images is both simple and effective. Like two pictures glued into a single page of an album, the filmic image is built by juxtaposing two videos on a black background. In the video on the right, the camera films a computer screen on which we follow interviews that Zaatari conducted with different people involved in the history of the images – the owners of the photograph, the photographers, or the collector. Through their accounts we gain access to the layers of memory attached to the images, the many anecdotes that accompany them, and much more information. To the right of the computer screen, we see the archivist carefully handling the pictures, revealing the images one after another as the narration continues. The camera in the second video, the left-hand one, concentrates on the images that are being revealed by the archivist, so that we can get a better look at them. This mechanism offers spectators the rare opportunity to grasp photographic objects throughout the parabola of their existence, from the instant they were taken to the gestures ensuring their conservation and archiving, as well as the memories that they evoke. “This picture on the left, where was it taken?” “This was taken on the road to the Dead Sea.” “Do you remember this occasion?” “I remember. I was very young. This is Palestine. I don’t recall when. I think I was 6 or 7 years old and we were watching the Graf Zeppelin, the German, in the sky.” This was probably in 1929, when the Graf Zeppelin blimp flew around the world. In this work, modernity is conveyed through children gazing at airplanes in the sky, the central train station in Cairo, and the ships sailing up the Suez Canal. It was modernity as synonymous with transportation and with the images, first photographic and then televised, disseminated in public places.

Photography Studios. “People used me to take photographs. I walked with my camera on my shoulder. Someone said, ‘Haschem, take my picture!’” recounted Madani. Zaatari dedicated many years of research to Studio Scheherazade in Saida, Lebanon, and the Cairo studio of Leon Boyadjian, an Armenian photographer better known as Van Leo. To Van Leo and two other photographers, Armand and Alban, the AIF devoted the 1999 exhibition Portraits of Cairo, which offered a suggestive, though partial, tableau of Egyptian society of the 1940s and 1950s composed of wedding pictures and portraits of the era’s political figures, such as Gamal Abdel-Nasser (Alban, Cairo, 1950–52) and King Faisal II (Alban, Cairo, 1955), and Egyptian and foreign actresses, including Dalida, photographed in stage costumes or with the pyramids in the background. In addition to being significant components of the history of photography in their regions, these studios were the subject of many photographs and videos made by Zaatari.

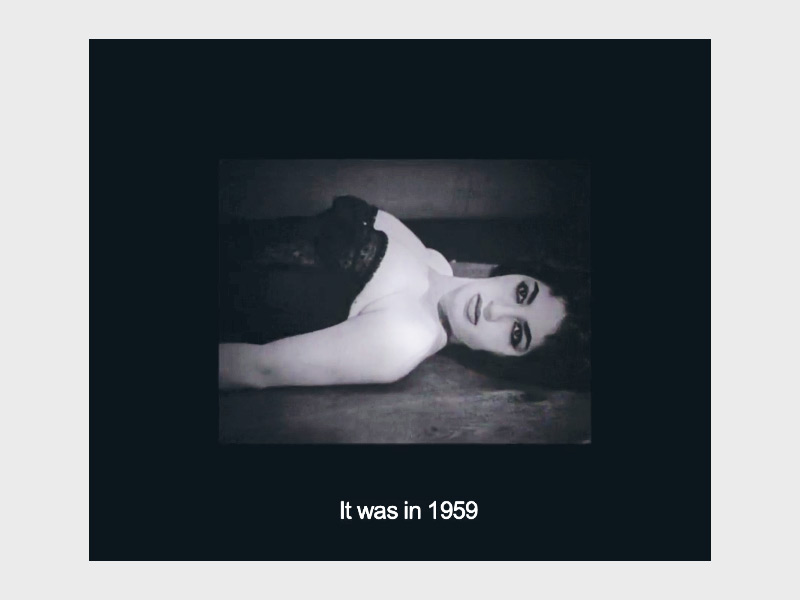

“I found a photograph of my grandmother signed Van Leo, Cairo, 1959,” says the first voice we hear in the video Her + Him (34 min., 2001–12), a filmed interview that Zaatari conducted with Van Leo during their encounter in Cairo in 1998. Through their conversation, we learn the story of Van Leo, who was born in Turkey, emigrated to Egypt, and, like many other Armenians, decided to devote himself to photography and opened a studio. This was Cairo in the late 1950s, when the city was a multicultural metropolis and the epicentre of incredible musical and artistic creativity. Although Van Leo’s story takes us back to the bygone times of an entire region – that of the Nasser era – and to a geography that now exists only in the imagination, his images are amazing for their modernity, the striking use of light, and the cinematographic poses of his subjects, a sign of the cross-fertilization of Egyptian and Hollywood cinema. “I have loved photography since I was young,” Van Leo tells us. “I collected magazines and photographs of Hollywood actors, and I studied how the photographs were taken.” And then he reveals his science of portraiture: the use of light, the angle of the camera, the expressions on the face at the decisive moment, the retouches. It is quite surprising to discover among his pictures numerous shots of nudes, black-and-white images taken by request in the discretion of his studio, where vulgarity gave way to sensuality of the female body, heightened by subdued lighting effects.

A similar concern with exhibition of the body – this time, young Lebanese men who want to display their masculinity – is also found in the pictures by Madani. Zaatari devoted his video Twenty-Eight Nights and a Poem (2015, 100 min.), commissioned by the Musée Nicéphore Niépce, to Madani’s practice. It is a moving tribute to the photographer, whose work was also the subject of two shows at the AIF: Haschem el Madani: Studio Practices (2004) and Haschem el Madani: Promenades (2006). The video camera lingers on Madani’s pictures taken in the city, near stores, in souks, and on the beach. His lens always offered a powerful opportunity for exhibition – sometimes in posed positions, others candid. In fact, it is in relation to the photographs taken by Madani on the beach that one of the most poetic sequences in the film is built. From negatives of the time examined under a magnifying glass by Madani, there is a sudden transition to images shot in slow motion and negative colours on the beaches of Beirut. Beyond the enchanting effect of the colour palette, which ranges from blue to ochre to purple, the association of the movement with the images in negative creates a highly disorienting temporal suspension, as if the negatives themselves were beginning to move. Only when the video returns to the black-and-white pictures are the images and the spectator brought back into their respective timeframes, and back to the narration. Madani sold his photographs in the studio: “Twenty-five piasters for the photograph alone, fifty with retouches.” The pictures in the series Objects of Study/Studio Scheherazade – Reception Space (2006), three large (110 × 600 cm) frontal shots, capture the studio’s atmosphere. They immerse us in its antiquated ambience, the pink walls covered with black-and-white pictures, a desk and a wardrobe filled with all sorts of objects and cameras and tools of the trade. The exhibition layout for display of these images strengthens this archival effect: pieces of furniture with half-open drawers from which emerge other images, reproductions of period photographs, retouching tools, cameras. And here, suddenly the photograph becomes a place.

The “Negative” of History. Jerusalem, 1948, the year of the Israel-Arab conflict: Antranick Bakerdjian photographs his destroyed house in the Armenian neighbourhood of Jerusalem and the fortification walls of the St. James Armenian convent that served as a refuge during the war. When he exposed this film, on which we note the signs of erosion and the brand of the film used – “DuPont,” “Nitrate,” “Panchromatic,” “Safety Film” – Zaatari chose, in The Body of Film (2017), to assign the film itself the role of witness to the conflict, these images having been produced when the photographer was deprived of his darkroom and had to move to another one. Yet, could this not be one way to use film to represent the “negative” of history – the “missing picture,” as Cambodian filmmaker Rithy Panh would say, displayed in the empty pages of family albums? This is the subject of the video On Photography Dispossession and Times of Struggle (2017, 30 min.). “I’ve lost all the photographs. All the photographs I have are reprints, my sister in Egypt made them for me. I asked her, as I didn’t have pictures of the children. I lost all the photographs. Those who found them scattered them in the street.” “Yes, I lost my house in Jerusalem. I couldn’t take anything with me.” From Jerusalem to Damascus, from Damascus to Beirut: sometimes, only the dates remain, the images having been lost, left in houses that the occupants were forced to abandon, strewn along a path with an unknown destination, and sometimes the temporary became permanent.

In the last part of the exhibition is another of the major themes addressed by Zaatari; his emphasis on the “corporality” of the image is a way of dealing with the question of the photographic matter and the processes of erosion, in which “accidents” that may occur to the film due to poor conservation become the metaphor for “accidents” of history that appear implicitly. The conception of the photograph that emerges underlines the aesthetic potential of film and its resemblance to archaeological artefact. One example is the image titled Archeology (2017), an enlargement of a negative from the collection of Moshen Yammine portraying the body of an athlete that seems to emerge from a stratum of dust. Aside from expressing the haptic dimension of the image, this effect, the result of deterioration of the medium, also aims to confer upon it a stratified temporality – a way of attributing a visual form to the history of the region and “materializing” the testimonial scope of the image. This is also the case for the project Face to Face (2017), for which Zaatari worked yet again from pictures taken by Antranick Anouchian in the early 1940s. These images, still on film, were made by superimposing and enlarging two negatives, one portraying a French soldier and the other, a member of the Tripoli community. In addition to highlighting the film support, Zaatari produces a image that is a significant referent, evoking the French presence in Lebanon since 1920; the French would leave the country only two or three years after independence, obtained in 1943.

“Do you remember Jerusalem? Do you remember when you left?” To this question, which even today summarizes the complex history of an entire region, Zaatari responds not by denying the sense of loss, but by returning to images taken at a time when history was still “undivided” (Un-dividing History, 2017). That is what is evoked in the series of eight calotypes showing the Dome of the Rock and the Temple Mount in Jerusalem. He made them by merging images by the Palestinian photographer Khalil Raad (1854–1957) and the Ukrainian Jewish director Ben-Dov (1882–1968), who immigrated to Israel in 1907. Two different images, certainly, but their points in common are still visible. If we try to see them.

Translated by Käthe Roth

Claudia Polledri is a post-doctoral student and lecturer in the Department of Art History and Film Studies at the Université de Montréal. She is also the academic coordinator of the university’s Centre de recherches intermédiales sur les arts, les lettres et les techniques. She holds a doctorate in comparative literature from the Université de Montréal; her subject is photographic representations of Beirut (1982–2011) and the relationship between photography and history.

[ Complete issue, in print and digital version, available here: Ciel variable 109 – REVISITER ]

[ Individual article in digital version available here: The Arab Image Foundation through Akram Zaatari’s Eyes: Or, Variations on the Theme of Photography

– Claudia Polledri ]