[Summer 2019]

By Colette Tougas

One purpose of the exhibition devoted to the Lazare collection at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts was to highlight thirtythree photographs that have been donated to the institution by Montreal collector Jack Lazare. To these donated photographs were added many others on loan from Lazare, adding up to an impressive show of more than eighty images produced by Canadian and international photographers.

As the title indicates, Individuals refers to portraits, and Places brings together landscapes and urban spaces, both real and imagined. To spatially accommodate these two aspects of the collection, the Contemporary Art Square, where the exhibition was presented, was arranged to create three spaces. The first was the large gallery, in the centre of which was found a small gallery (the second space). The third space was the small gallery’s exterior walls, on three of which were hung four large photographs; the fourth wall featured a collection of prints by Julia Margaret Cameron (1815–79).

It was Cameron’s work, which Lazare saw at an exhibition in New York in 1999, that awoke his passion; up to then, he had collected figurative paintings. Following this discovery, he began to acquire not just images by Cameron but also those by renowned contemporary photographers and important American modernist figures.

Cameron’s fourteen albumen prints are, in fact, inspiring. These delicate, almost mystical portraits are bathed in a mysterious light that sculpts the faces and the draping of the garments. It is understandable that the collector of paintings was first attracted to such pictorial photographs.

The exhibition highlights the collector’s eye. Lazare seems to have favoured photographs that draw attention to staging and composition, gesture and poetry, private life and social climate – and the exhibition path traced by curator Diane Charbonneau successfully underlines these features. The first wall in the large gallery, devoted to “places,” starts with a “fabricated industrial landscape” shot in China by Canadian photographer Edward Burtynsky and concludes with two images by Italian photographer Paolo Ventura set in a papier mâché décor – thus, also fabricated. Between these two poles are a series of variations on the theme of urban space – interiors, façades, streets – superimposed, recomposed, transposed.

On the back wall is a series of portraits that connect like a sentence in sign language, written by arms and hands. To the young woman leaning on her elbows in a restaurant by Hannah Starkey, at the beginning of the section, responds, at the end, Woman at Entrance, by Teresa Hubbard and Alexander Birchler, whose folded elbow and red blouse seem to echo the pose of Starkey’s young woman in a sort of set of parentheses. The gallery of figures deployed here includes, among others, an elderly couple, two ladies in a Venetian café, a couple between ecstasy and climax, and a woman with a pale face and a sombre gaze. This series brings out some photographers’ refined art of mise en scène, and the innate capacity of others to capture reality On one of the four walls of the small gallery, opposite, a large photograph by Pascal Grandmaison shows a woman rendered pensive simply by holding a pane of glass in front of her – a proposal that is both simple and effective.

The following wall displays fourteen photographs continuing the theme of individuals. Dominated by black-and-white images, this section is reserved for relative close-ups with almost no background. Thus, we see intimate ambiences personality of a series of people, mainly women (twelve of the fourteen), including one luminous shot of a young Marilyn Monroe by Elliott Erwitt, an imperially haughty self-portrait by Raymonde April, and a destabilizing portrait of a young woman in a shabby tank top by Bill Henson. Opposite, on the third exterior wall of the small gallery, two portraits of equal strength are side by side: one of a man with a shaved head, in profile, whose pose denotes fierce determination (by Willie Doherty) and one of a woman of a certain age, her face overcome by an invisible tragedy (by Katy Grannan).

On the fourth exterior wall of the small gallery, a large photo of a highway exit toward Las Vegas, by Albert Watson, leads to the landscape – in this case, that of an improbable red-and-purple sky against which stands out a series of road signs announcing various gambling offers. It also points to the entrance to the small gallery.

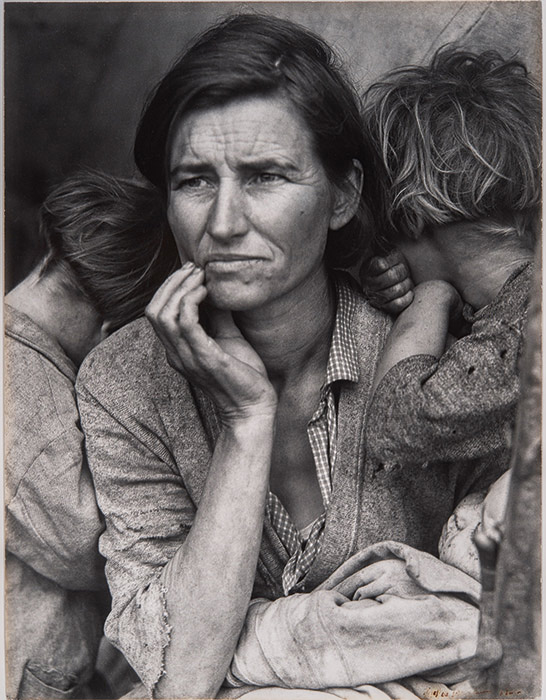

This more intimate space contains forty-seven landscapes and individual and social portraits. All of them small in format, the photographs cover almost a century of production – from 1916 to 2015 – the oldest being by American photographer Paul Strand and the most recent by Frenchman Jean-Baptiste Huynh. Starting with the celebrated and touching Migrant Mother by Dorothea Lange (1936), the series of sixteen images on a first wall shows artists, street people, and men, women, and children from various countries, including a remarkably understated portrait of an Ethiopian man.

The back wall offers a series of photographs dedicated to different living conditions. Among them is a fairly large nocturnal image by Alex Majoli, taken in the Congo in 2013, in which the flagrant misery gives pause for thought, as well as two photographs by Gordon Parks illustrating disturbing aspects of American society: the first, from 1956, shows an elegant woman whose child is in the arms of an African American nanny in the Atlanta airport; the second, from 1967, shows an African American family in front of a bureaucrat from the “poverty commission” in Harlem.

People in landscapes or in movement comprise the next chapter: a line of people in a field, a homeless family on an empty road, a woman walking her dog, a little girl in blue in a hallucinatory landscape. This last photograph makes the connection to formal doubles with vehicles, a deserted landscape seen from a train, and another double of passengers in a train. On the last wall of the small gallery, a photograph by Astrid Kruse Jensen shows a woman sitting in a boat behind a curtain of grasses, poetically invoking the themes of landscape, portrait, and movement.

In the large gallery, the seven last photographs are arranged to trace a sort of horizon line. Landscape with tree, pyramid-shaped industrial landscape, marine landscapes, nocturnal and terrestrial and field fixed in wintry fog, lead to a collection broadens this notion to include the human family. How can we not sense, through these faces and these places, inhabited or not, an empathetic gaze at a humanity that is always to be challenged and reinvented? It is the gaze, first, of the art photographer, and then that of the knowledgeable collector who thus reveals a given civilization in a given era.

Translated by Käthe Roth

Colette Tougas works in the contemporary art field in various roles. She is the author of texts on art and of fiction.

Jack Lazare is a Montreal collector and businessman. He discovered art photography in 1999 and has since built a remarkable collection of Canadian and international works.

[ Complete issue, in print and digital version, available here: Ciel variable 112 – COLLECTIONS REVISITED ]

[ Individual article in digital version available here: Collection Lazare : États d’âmes, esprit des lieux — Colette Tougas, Portraits of Families with Nature (Still Life or Other) ]