[Winter 2020]

Par Laurie Milner

Is it the greyness of the April afternoon that makes the Rene Blouin Gallery seem so luminous as I enter Geneviève Cadieux’s exhibition Ghost Ranch?1 I had heard the buzz among artists and colleagues that this was a show to be seen – a virtuoso production by an august Montreal artist – and I have come to do just that: to observe the concrete facts of the work, apprehend the artist’s language, and sense the realities it evokes. What strikes me first is the light – it floods the gallery, announcing itself as an essential element in the work.

I.

A monumental photograph in a simple frame leans against a wall in the first room of the gallery; before it, beyond a column, a gilded sphere sits on the floor. I am struck by the simple geometry of the installation – a rectangle and a sphere – and the way it defines and activates the space. The horizontal axis and rectangular shape of the photograph align with the logic of the architecture, while its pitch and mass give it a conditional, bodily presence. The sphere, gilded with gold leaf on one side and palladium on the other, is precisely placed – its demarcated circumference stands perpendicular to the floor and parallel to the photograph. It reflects and refracts the ambient light in the gallery, setting up a dialogue with the photograph, the space, and me.

Sphere (day and night) brings to mind an orbiting planet, with one hemisphere reflecting the golden light of the sun and the other the silvery light of the moon. There is a discreet but deliberate facture to the surface, an evocation of terrain, water, flesh. I am caught by the tension between the tenderness of the materials – thin leaves of precious metals delicately pressed onto a viscous base – and the technical exactitude of the line where gold meets palladium – the fine cut it makes into the skin of the sphere. There is both precision and solicitude in the execution, flow, and rupture in the otherwise perfect geometrical form.

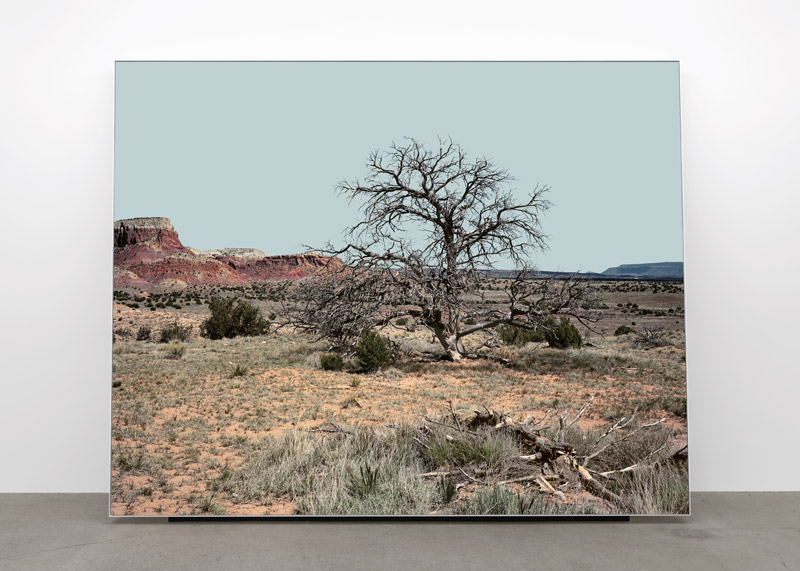

The photograph, Lonely tree (day), presents a vast, sundrenched desert landscape with a gnarled, barren tree as the focal point. The depth and clarity of the image give it a documentary quality, as though it faithfully conveys the section of sky and land that was seen by the artist through the lens of her camera. The tonality across the landscape is even – soft ochres, greens, and reds; a tinge of blue on the most distant landforms conveys the effect of atmosphere on perception. The naturalistic illusionism is enhanced by the monumental scale and floor-level installation – it is as if I could walk into the pictured landscape – and the classical, Poussinesque composition of the work: red cliffs in the distance frame the view, a fallen tree trunk leads the eye diagonally from the lower right corner to the central tree, and a clearing in the desert shrubbery at the bottom left offers a point of imaginary access – it winds first to the left, then to the right in front of the tree, and then left again, before zigzagging into the distance. One branch of the tree extends to the left, mirroring the jagged horizon line just below it – an echo of Cézanne.

A delicate pattern of gold leaf on the surface of the photograph extends and then abruptly halts the illusionary, absorptive quality of the image. It shimmers with the diffused light in the gallery and heats up the scene, as though the winding path leading into the desert were ablaze with the radiance of the sun. This perception comes like a flash, a moment of acute experience – a punctum – and disappears almost as quickly, as flat, evenly painted lines of gold come into focus. Meticulously rendered according to a precise mathematical pattern, the lines become an abstract drawing – a nod, perhaps, to the delicate geometry of Agnes Martin, an artist who, like Cadieux, was lured by the desert. The gold striations hum with an electrical energy that brings to mind the scanning technology used to create the picture and my own desire to see, to scan the work for its message.

The sky is peculiar – a uniform expanse of pale turquoise that further confounds the illusionism and intensifies the affective charge of the work. There is an awkwardness at the juncture of sky and earth, where plane and illusion abut – a cut in the reality effect of the image: it becomes set, tableau. (Later, Cadieux explains that the colour of the sky was carefully keyed to the iconic blue of early American Westerns, and I remember hand-painted desert scenes, flooded with light but showing no source of illumination apart from the projector.)

The total effect is stillness, as though the pulsing spirit of the dessert had been momentarily crystallized by the photographic apparatus and gesture.

I look back at the sphere: it has become an eye, a lens, an open aperture.

II.

In the second room, light is replaced by darkness. Two monumental photographic works – one square and the other a horizontal diptych – face each other across an open space. Both are rendered as black-and-white negative images, creating an otherworldly, nighttime effect. Both are enhanced with bold applications of palladium, adding drama and intensity. In both, pitch-black skies join shimmering land forms along sloping horizon lines that introduce instability into the images.

The first photograph, Lonely tree (night), features the same barren tree that was in Lonely tree (day); but, here, the negative has been cropped and enlarged so that the tree appears as a phosphorescent pyramidal form that dominates the image. The trunk leans slightly to the left and crosses the horizon line, as though suturing the awkward join of sky and earth. A vascular network of branches, highlighted with palladium, spreads laterally from the trunk; at the base, it touches the outer edges of the support, defining the limits of the field of vision.

Fine ribbons of palladium painted on the photograph trace the jagged outline and sinewy surface of the tree, giving it an eerie incandescent quality. Like silver salts in analog photography, the palladium lines, so sensitively rendered, reveal an image – the photograph of a tree – while simultaneously creating another – an abstract drawing, perhaps, or gigantic fingerprints on the surface of the photograph.2

In the second work, Ghost Ranch, starry night, a desert landscape flows across two closely hung photographs in undulating horizontal bands. The photographs, which are made from different negatives, represent distinct yet resonant views. In the left-hand image, a dark pyramidal rock formation breaks the sloping horizon line; in the right-hand image, a semi-circle of luminous shrubbery does the same. The perspective is deceptive: the shrubbery and rock formation, which, in actuality, are of vastly different scales and locations in the distance, appear, in the images, as equal in size and on roughly the same plane. This spatial ambiguity is compounded by the presence of a small yet fully grown tree to the right of the shrubbery that, curiously, resembles a tree that Georgia O’Keefe painted while living at Ghost Ranch. The formal symmetry and spatial syncopation in the two images provide the framework for endless variation. Trees, desert scrub, and grasses take form as bursts and trails of light – as though the powdery ground of a charcoal drawing had been lifted with a fine brush to reveal the life force of desert vegetation and rock formations.

Up close, the precision and clarity of the view gives way to evanescence. Forms appear to be in motion, to melt, to run down the surface of the image, to spark and fly; small details become topographies, universes, cosmologies.

It is the sky that knocks the image into the contemporary sublime – a flat plane of velvety black punctured by a vortex of palladium stars. Precisely rendered in a moiré pattern, the stars flare forward, beyond the picture plane, to absorb and transport the viewer. The effect is mystical: an evocation of the immanent power of nature, the wonder of the cosmos, the mystery of existence, and the technical and conceptual tools we have to express it.

III.

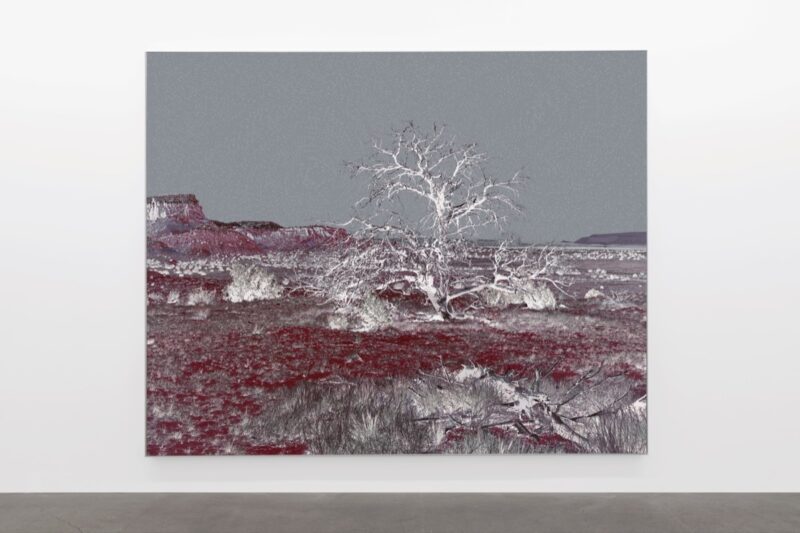

In the third room, the desert landscape with tree and the gilded sphere reappear, as do colour and light. The photograph, Lonely tree (dawn) – now hung on the wall in the space of contemplation – is a negative image coloured in tones of red, brown, grey, and mauve. Sphere (dawn), sits offside on the floor, at an acute angle to the photograph. The effect is an atmosphere of incipience.

In the photograph, Lonely tree (dawn), the colour red first attracts the eye – it seems to seep out of the ground and pool like blood along the winding path in the photograph. I am reminded of the long history of the desert where the photographs were taken, the millennia during which it has been home to indigenous life, the fragile ecosystem that it is, and the threats that it faces. Staying with the image, the associations shift: the red becomes both a mark of injury and a sign of fecundity, nourishment, and the possibility of renewal. The grey sky is filled with swirling palladium stars. The reference is Starry Night, but without the wild colouration – the delirious optimism undercut by despair – conveyed by van Gogh. Here, there is mystery, quiet, and awe.

Although the central tree was clearly dead in Lonely tree (day) – fixed in time by the natural process of petrification and the photographic gesture – here, its state is uncertain. It appears luminous as it rises from the red soil. Is it in transformation? Is it adapting? Does it have an afterlife? Are its twisted branches responding to the magical dance of the stars, or are they, like ashes, about to fall?

Sphere (dawn) stands at the end of the exhibition. Its skin of precious metals is still soft. On one side, the palladium gives way to a narrow wedge of gold leaf. A new day is dawning. An aperture is opening.

Touched by the reflections on time, perception, resilience, and transformation that Cadieux has shaped through light, I step back outside, into the drizzly Montreal afternoon.

2 Geneviève Cadieux presented this analogy between the function of silver salts in analog photography and the palladium lines in Lonely tree (night) in an interview with the author (June 28, 2019).

Laurie Milner is an art historian and writer based in Montreal. She teaches modern and contemporary art in the Art History Department and creative and critical writing in the MFA Studio Arts Program at Concordia University. She also runs her own writing and editing business.