[Summer 2021]

A Disappearance Story

By Sébastien Hudon

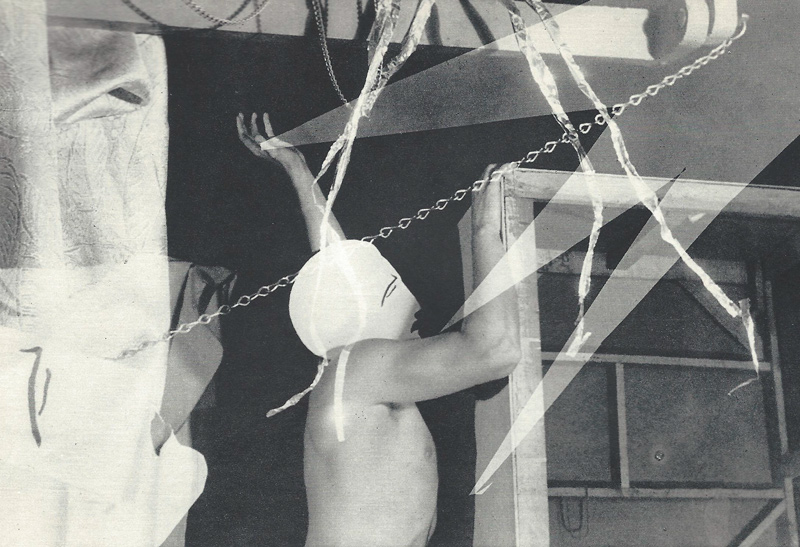

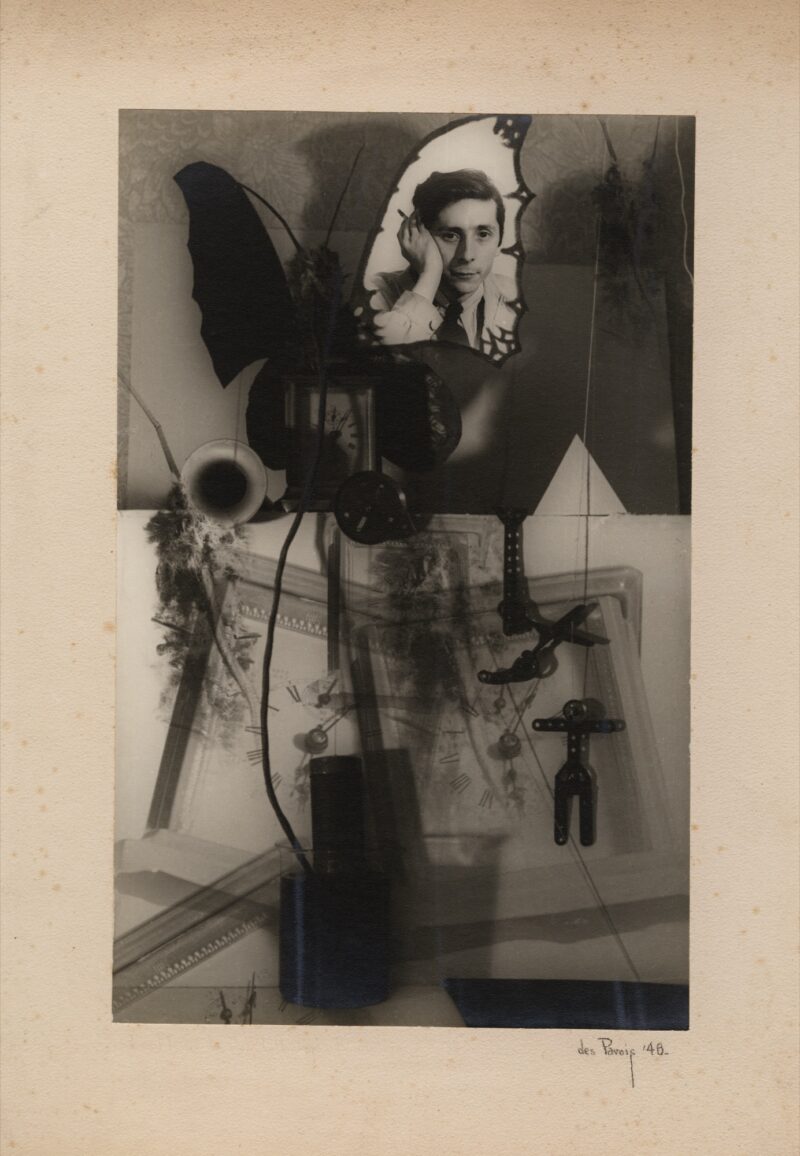

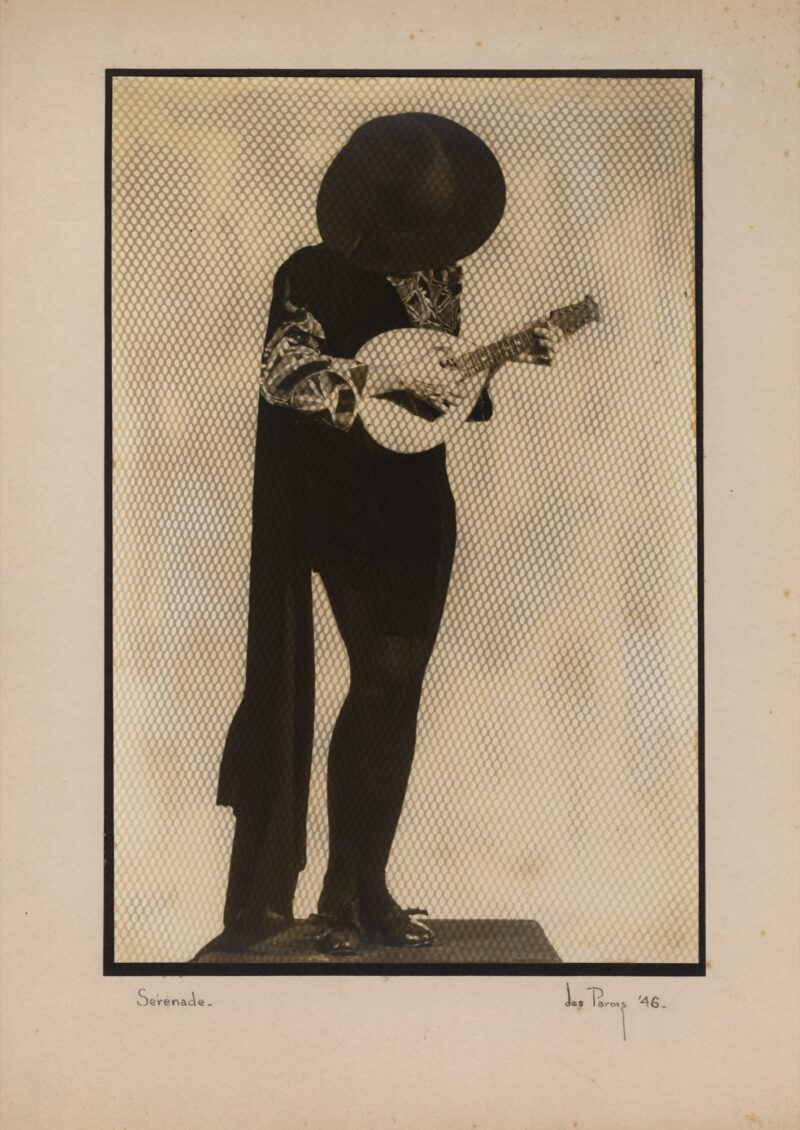

For an exhibition by artist Guillaume Adjutor-Provost titled Belles eaux,1 I was invited to show and introduce three rare works (facsimiles) from an exceptional grouping that I had just discovered. Acquired at an auction held in France in October 2020, the grouping is composed of gelatin-bromide monotype photomontages on paper laminated onto mount board. Signed and dated between 1946 and 1948, these remarkable works hadn’t been seen in Montreal for more than seventy years. Their creator remains, to this day, almost unknown to historians. His name: Évariste Desparois.

The fact is, little about Desparois and his works has survived to the present day. Aside from a short article by professor and collector Gilles Rioux (1942–95), published in a special issue of Vie des arts devoted to surrealism in fall 1975, and a few photographs conserved at the Musée national des beaux-arts de Québec, barely anything about him can be found in the literature or in institutions. I recently learned that he was born in Montreal on May 18, 1920,2 and that he studied at Collège Mont-Saint-Louis from 1935 to 1939. But his personal story remains elusive, and currently it is only through the photographs that he disseminated and newspaper accounts of his public appearances that we have access to the period during which he was most active, from 1945 to 1975.

From November 1945 to April 1946, according to newspapers and other publications of the time, Desparois (sometimes spelled “Des Parois”) was seeking out artists (painters, musicians, stage and radio performers) for a photography exhibition, which did not take place until 1948.3 As a contributor to Le PasseTemps, a Montreal cultural periodical, he published portraits of emerging and established figures. The photographs of painters Suzanne Duquette, André Jasmin, and Alfred Pellan4 were in a more personal style, standing out from his production during this period for their radical composition.

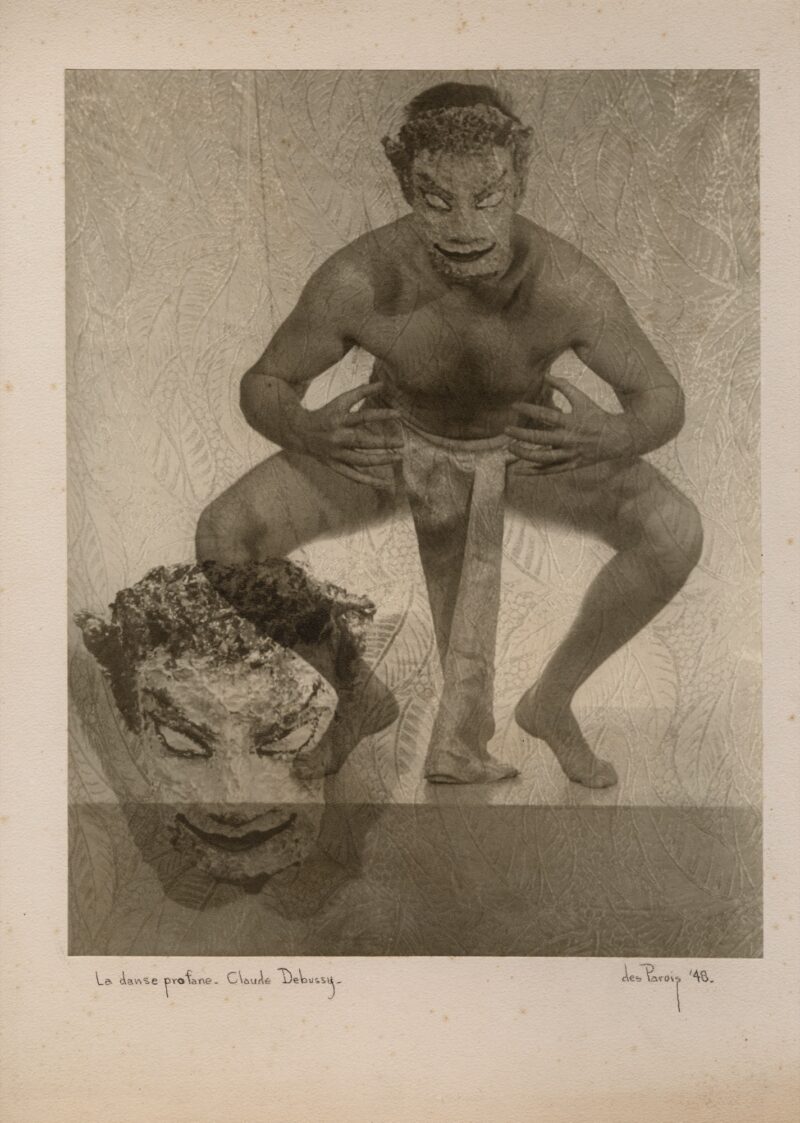

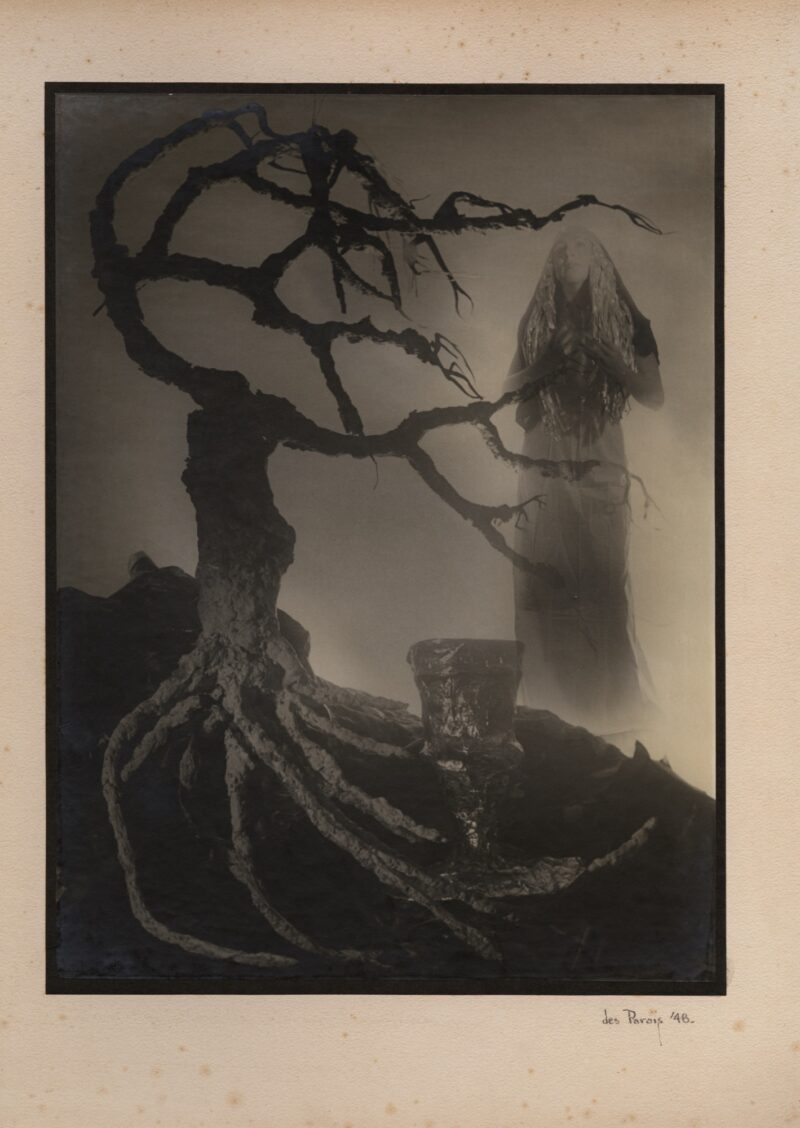

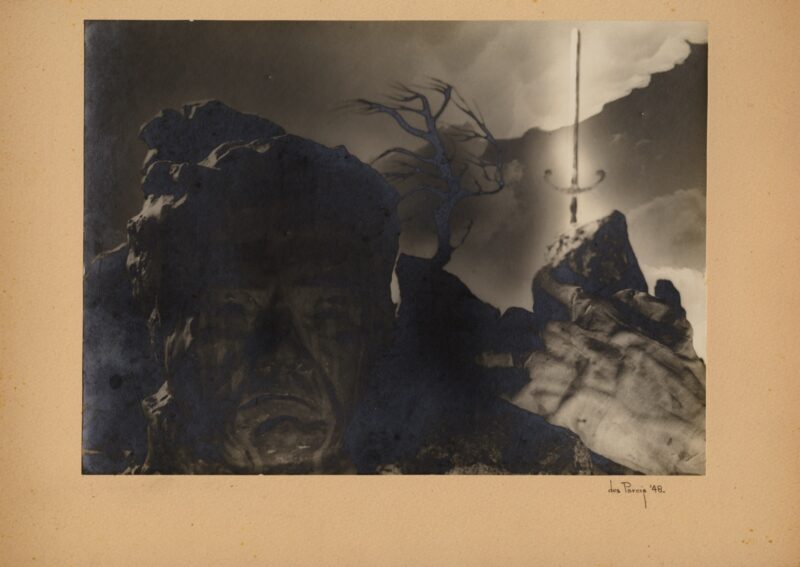

The next, and crucial, period is the best documented. In August 1948, Desparois exhibited his work at a short-lived show in the offices of Le Passe-Temps. In a photograph taken at the event, he stands in front of one of his images. In the picture, we can recognize, hung from a string reminiscent of darkrooms, his Danse profane – Debussy and L’oiseau de feu – Stravinsky. At a scintillating moment in the art community, two weeks after the launch of the Refus global manifesto, Desparois was presenting, for the first time, a strange, surrealistic series of photomontages. Inspired by poems by Aloysius Bertrand and Charles Baudelaire, as well as the music of well-known composers – Beethoven, Chopin, Debussy, Ravel, Satie, Stravinsky, Wagner – this unusually coherent corpus made a name for him both in Quebec and abroad. It is from this series that most of the works I found and reproduce here – a small sample of the more than thirty pieces in the original grouping – are taken.

These photomontages, created by the assemblage and superimposition of negatives –not by collage – and designed as unique “tableaux,” made Desparois a trailblazer. It was only much later that artists in Quebec began to use this technique, which was adopted by students at the Ateliers d’arts graphiques under the mentorship of Albert Dumouchel and Arthur Gladu, as well as by Jean-Paul Mousseau and Robert Millet. Such works are extremely rare and isolated, however, as I’ve observed from years of research on experimental photography of that era. As far as I know, there is nothing close to so dazzling a production in terms of numbers, complexity, unified conception, and influence as Desparois’s. The reception given his works in 1948 underlines their quality: “The artist uses superimposition . . . he uses the process with enough flexibility that his associations do not seem forced and create a perfect illusion.”

Off to Europe. A few days after this show, Desparois left Montreal in the company of writer and journalist Françoise Gaudet-Smet. They were headed for Sweden, where Gaudet-Smet invited Desparois to document and provide illustrations of folk arts and traditions; the story of the trip was recounted in M’en allant promener (1953). Remembering the transatlantic crossing, Gaudet-Smet praised in the publication her collaborator’s great passion for music, which infused his creations. Desparois carried all his photographic compositions in a portfolio that he rarely let out of his sight. During this trip and over the following two years, he had exhibitions in a number of European cities. He made an impression everywhere he went. In Stockholm, the Swedish Institute organized a gathering of artists in his honour and Foto, one of the biggest Scandinavian magazines of the time, devoted a multi-page portfolio to him, with large-format reproductions. In Finland, he presented his works in an exhibition at the Helsinki Photography Club.

It was in Paris that triumph awaited him. In the avant-garde gallery where Jean Dubuffet had come to prominence – L’Arc-en-ciel, 17 Rue de Sèvres – the vernissage of Deparois’s exhibition was spectacular. A review in a Montreal daily described the shock wave: “More than two hundred people were invited from among the elite of the Paris art world. Évariste Desparois’s works were presented by Renée Moutard-Uldry of the newspaper Arts, with a highly complimentary essay called ‘Photos imaginaires.’” This would be the title for this body of work from then on. That evening, among the guests were authors Marcel Aymé, Jean Cocteau, Hélène Jourdan, composer Olivier Messiaen, and established photographers such as François Boucher, Brassaï, Yvonne Chevalier, Laure-Albin Guillot, and Daniel Masclet.

Desparois met with members of European surrealist groups with internationalist aims. He spent time with André Breton, became close friends with photographer Emmanuel Sougez, and joined the circle around composers Arthur Honegger and Georges Auric. One article gives a good idea of the discussions around his work: “Paris has consecrated him! Many people have said to him, “At twenty, you have produced what we had dreamed of producing and have not yet accomplished at fifty. You have surpassed the usual limitations of photography; you have truly achieved a superior art.”

In June 1949, Desparois went to Brussels with his photographs “that had seen great success in Paris thanks to their technical quality and their poetic content.” At La Petite Galerie du Séminaire des arts, he caught the attention of the international group CoBrA, which mentioned him in an issue of its eponymous magazine dedicated to photography and experimental film. The inaugural exhibition of this group, which was seceding from surrealism, took place right before Desparois’s. One of the final appearances of his works was in the first major international photography exhibition produced by UNESCO, included in the “experimental” category.

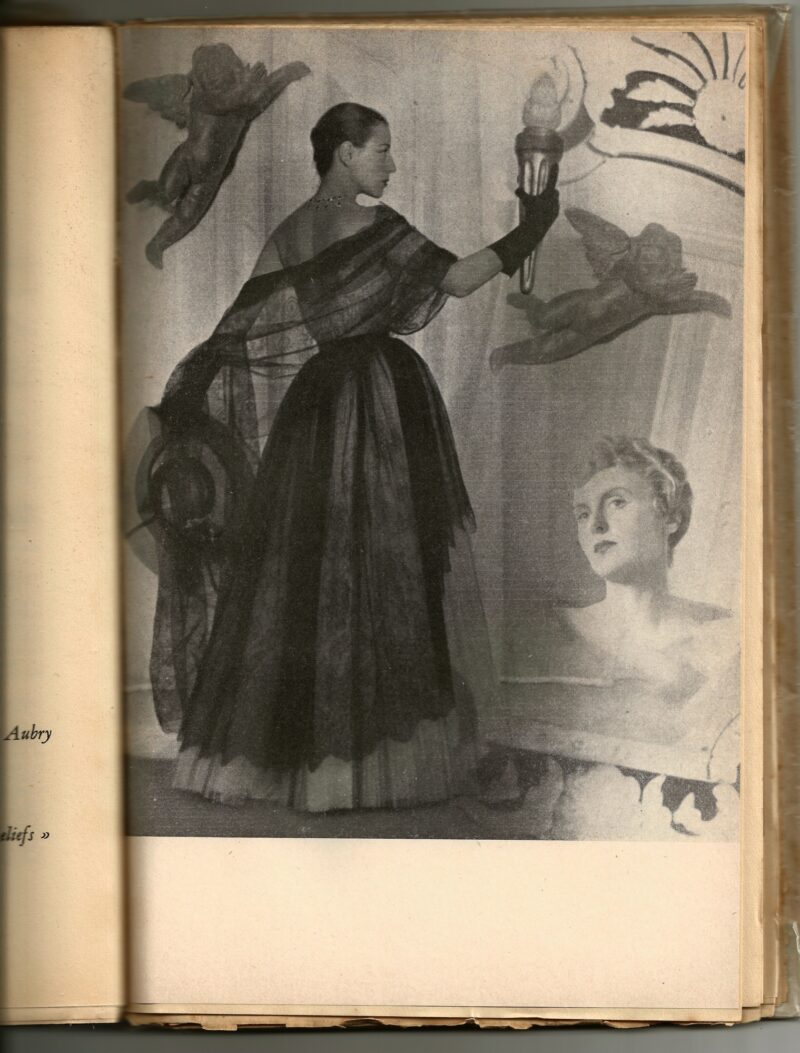

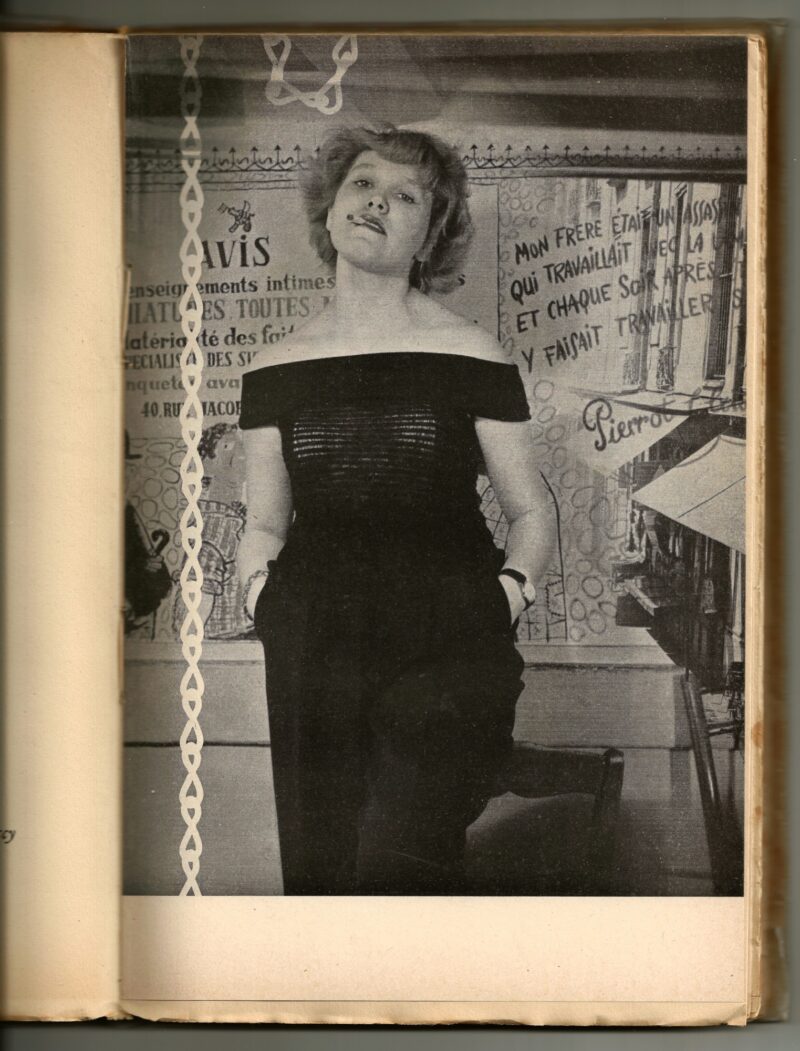

From 1949 to 1958, Desparois lived in an effervescent post-war Paris. My research has brought to light his activities as a photographer for a collection of works by French poets and intellectuals then in vogue. He was asked to provide the visuals for the publication L’Éternel Féminin, allying himself with high-fashion creators and designers (Balmain, Dior, Ricci). The result was fifteen stunning compositions, photomontages combined with photograms illustrating an ingenious concept: portraying the goddesses of Olympus as if they were alighting in the Champs-Élysées. A modern muse, Existentialie, was created in response to Simone de Beauvoir’s essay “Qu’est-ce qu’une Femme ?” The thread of his life that can be followed in Paris more or less breaks there, around Rue Rousselet.

One question remains shrouded. According to a French magazine, Desparois was the “top photographer of Studio Niepce in Paris” at 19 Rue Rousselet, run by the “granddaughter of the inventor of photography.” That woman, the resilient Janine Niepce (1921–2007) – who was to become one of the first female photojournalists, joining the Rapho agency in 1955 – was actually the great-niece of the pioneering photographer. It would be logical that she and Desparois, who were about the same age, had a relationship. Unfortunately, it’s impossible to know if and when such a liaison began.

In March 1952, Jean Paul Riopelle had a show at the same address on Rue Rousselet, then called Galerie Henriette Niepce (for Janine’s sister). Between 1955 and 1960, Paul-Émile Borduas had a studio at that location. In fact, it was likely Janine Niepce who, just before Borduas’s death, took a series of portraits and images of his studio that are still authoritative today. Did Desparois meet Riopelle and Borduas in Paris? His name appears in neither the correspondence nor the works of the two artists. Given his closeness with the Niepce sisters, this utter absence seems suspicious.

Everywhere and nowhere. As mentioned above, news of Desparois’s successes in Europe reached Quebec only occasionally. He pops up in an interview granted by author Germaine Guèvremont, in which she recounts the financial difficulties that he was having. His few trips to Montreal for exhibitions of his “photos imaginaires,” such as the one held at the Cercle Universitaire, drew the interest of the local press.

[They are] composed, fabricated of specific negatives, artfully chosen and sensitively arranged. Each photograph is original in that it is created from scratch from two, four, or up to eleven negatives. . . . Many remind us of certain surrealist films, such as Buñuel’s Le chien andalou, and others by Maya Deren. This explanation surprised him. “I saw those films in Paris,” he said, “a few months after I made these photographs.”

Desparois was thrilled with his reception in Paris. His talent was applauded, his perseverance appreciated. Among the abundant literature was a piece by Paul Gladu: It seems to me that the contribution of this poet-photographer resides in his particular use of a highly nuanced and extended pictorial vocabulary. The stumbling block for all photographers is no doubt reality itself. How can we avoid this? . . . Some contemporaries have striven to transpose the real in a way that conveys their thoughts. . . . But few, to my knowledge, have brought disparate elements together within one frame while achieving unity of intention.

When he returned to Montreal for good in November 1957, Desparois had his last known exhibition. It took place in the tourism bureau and brought together seventy-five photographs taken in Paris and elsewhere in France, taken during a presumed last stay with Janine Niepce. In the wake of this exhibition, he was assigned to the television news service of Radio-Canada as a freelance camera operator. Until the early 1960s, he was said to be, in turn, news cameraman, photojournalist, and professional photographer. His final important appearance in print was in Jean Palardy’s book on antique furniture of French Canada, published in 1963.

Desparois’s art was not mentioned again until almost fifty years later, in an article by Gilles Rioux in Vie des Arts, accompanied by works taken from the 1948 grouping. Rioux was apparently the last person to meet him and talk about that work, providing us with the final traces we have of Desparois. What could have happened for a contemporary artist who was among the signatories of Prisme d’yeux and Refus global to be so utterly wiped out of the history of art and photography in Quebec? The surprising disappearance of Évariste Desparois, and the splitting up of his body of work, bespeaks the fate of so many artists. Between facts and hypotheses, much mystery remains; I continue my search for the person who will say, “Je me souviens.” Translated by Käthe Roth

1 Occurrence, espace d’art et d’essai contemporains, Montréal, du 18 mars au 24 avril 2021.

2 Merci à Nathalie Thibault au Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec, par qui nous avons pu consulter son acte de baptême.

3 [Anonyme], « Rumeurs et potins », Photo-Journal, Montréal, 15 novembre 1945 (p. 28), 31 janvier 1946 (p. 30), 25 avril 1946 (p. 29).

4 Ceux de Duquette et Pellan sont aujourd’hui conservés au Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec.

5 Nous avons retrouvé dix-neuf images du corpus original ; nous avons les originaux de huit d’entre elles, onze autres nous sont connues par des reproductions. En ajoutant les titres d’une quinzaine d’œuvres inconnues et en tenant compte que les titres peuvent parfois s’être recoupés, nous arrivons à un total d’environ 35 œuvres.

6 Anonyme, « Paysages poétiques », La Presse, Montréal, jeudi 26 août 1948, p. 16.

7 Elle a fondé la revue Paysanna et la colonie de Claire-Vallée, un « Foyer de service social rural », qui avait pour objectif de valoriser les productions domestiques et du terroir par l’enseignement et la mise en commun de savoir-faire traditionnels.

8 Ulf Hård af Segerstad, « Surrealism än en Gång » Foto, no 1, janvier 1949, p. 12–15.

9 Anonyme, « Photos de Des Parois », La Presse, 26 janvier 1949, p. 8.

10 Une photo de Desparois nous montre Françoise Gaudet-Smet et son fils, accompagnés de Jean Cocteau. Nous pensons qu’elle a été réalisée le soir du vernissage. https://numerique.banq.qc.ca:443/patrimoine/details/52327/3108813?docref=ynPM9TyMlvsJA-x_TpdZrg (P1000,S4,D87)

11 Auric illustre un de ses articles de photographies de Desparois. La référence exacte nous échappe, n’en ayant trouvé que la dernière page (!).

12 A.A., « Le monde irréel d’Ev[ariste] Desparois », La Presse, Montréal, 4 juin 1952, p. 24.

13 S. Y., « La Petite Galerie du Séminaire », Les arts plastiques : carnets du séminaire des arts, éd. de la Connaissance, Bruxelles, no 3-4, mars-avril 1949, p. 146.

14 Madeleine Quenault, « Luigi Veronesi », Cobra III, Bulletin pour la coordination des investigations artistiques lien souple des groupes expérimentaux danois (host et spiralen) belge (surrealiste-revolutionnaier), hollandais (reflex), Bruxelles, juin 1949, p. 6.

15 Exposition mondiale de la photographie, [Catalogue de l’exposition tenue du 15 mai au 31 juillet 1952], Genossenschaft Photoausstellung, Lucerne, 1952, 48 pages.

16 Simone Chevallier (dir.), L’Éternel féminin, coll. La voix des poètes, vol. 2, Paris, Cahiers d’art et d’amitié, 1950, 297 p.

17 Anonyme, « Au service du tourisme français », Radiomonde et télémonde, Montréal, 7 juin 1958, p. 7.

18 Ruth Körner, Kanada: Junge Welt, Vienne, Europa-Verlag, 1954, p. 173.

19 Anonyme, « Imagination et photos réunies », Le Canada, Montréal, 5 juin 1952, p. 14.

20 Paul Gladu, « Évariste Desparois », Le Canada, Montréal, 20 juin 1952, p. 4.

21 Jean Palardy, Les meubles anciens du Canada français, Paris, Arts et métiers graphiques, 1963, 411 pages.

22 Gilles Rioux, « Desparois : La Lanterne Magique », Vie des Arts, Montréal, vol. 20, no 80, 1975, p. 50-51.

Sébastien Hudon, artistic director of La Bande Vidéo, is an art history researcher and independent curator. Among the exhibitions he has organized are Photographes rebelles à l’époque de la Grande Noirceur (1937–1961), Quelques moments d’utopie, NYX/1993*2013, and Jean Soucy, Peintre Clandestin.

[ See the magazine for the complete article and more images : Ciel variable 117 – SHIFTED ]