[Summer 2021]

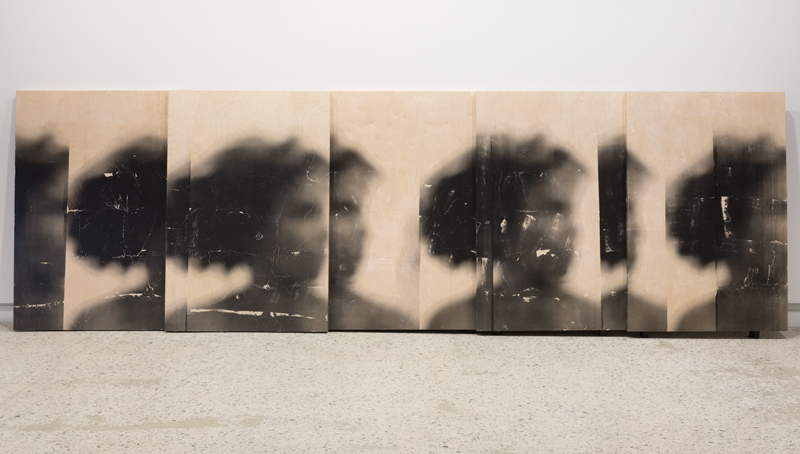

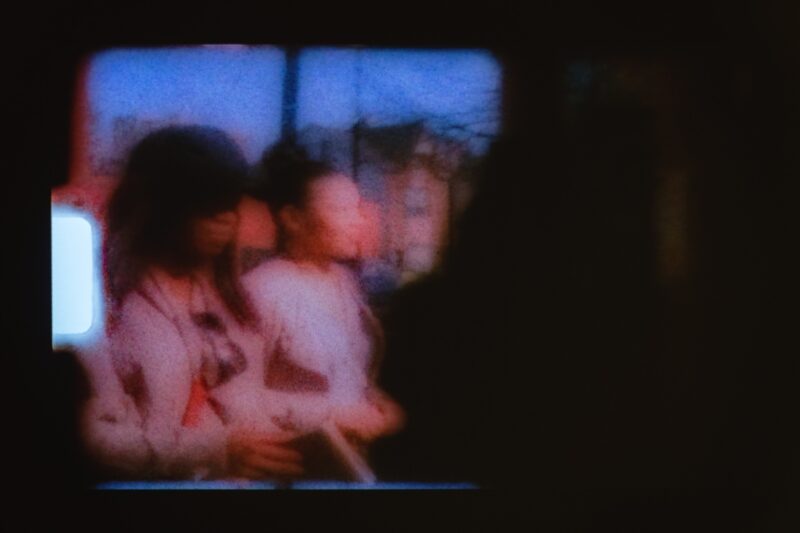

Works from series: Smith, Blur; Video: Walk on by

By Érika Nimis

Optica, un centre d’art contemporain, Montréal

16.02.2021 — 03.04.2021

After long months of forced restraint, what a pleasure it is to return to visiting visual arts venues in person! I tested out this pleasure by going to Optica to see Toronto artist Sandra Brewster’s first solo exhibition in Montreal.

Brewster, whose parents are from Guyana, attends closely to the multiple migration experiences of Caribbean communities and addresses in great detail the questions of identity and image in her works. Deconstruction of the portrait and the representation of racialized and Black people are at the heart of her creative process. In particular, she transfers images onto various supports (paper, wood, video) – images incorporating phonebook pages, as in the series Smith (2011–19), or photographic portraits, as in the series Blur (2018–19). The image-transfer technique works as a metaphor for movement – that, among others, of her family’s migration to Toronto in the late 1960s.

In the first gallery, our gaze is grabbed by a series of ninety-six black-and-white silver-print bust portraits. We seek, in vain, to grasp the expressions in all of these faces, which are strangely blurred. In fact, Brewster used long exposure times and asked her models to move, to go beyond the edges the frame, as if to defy the heavy heritage of photographic practices inherited from European colonialism. Both the actual and the figurative identities are elusive, troubled by the random effects of the transfer, which Brewster links to the complex life experiences of Caribbean communities. “Blur is the Black body in motion, both collectively and individually,” notes Concordia University professor Nalini Mohabir, in an essay commissioned for the exhibition. For my part, I can’t keep from thinking of the work of Montreal photographer Serge Emmanuel Jongué (1951–2006) who, “driven by nomadism, his inner voyage, and a quest for identity, [made] room for more personal writing while provoking a critical reflection of traditional ideas about identity and personal memory.”1

In the second gallery, we find the next part of Blur (presented in its entirety at the Art Gallery of Ontario in 2019–20), Untitled (Blur, Self), a blurred self-portrait repeatedly transferred onto five large wood panels, and the short video Walk on by, a transfer of a short montage of prints shot in colour with a Super 8 camera. About this work, Mohabir writes that “the soft blurriness and timeless quality. . . implies not a recent arrival but long histories of presence.” In these images, in colours of the past, deliberately amateur in quality, Black passersby stroll and attend to their daily occupations in the lively streets of a carefree Toronto, far from surveillance cameras.

Facing Blur, an older series dear to Brewster’s heart, Smith, takes up the idea of the serial portrait on three panels papered with a grid of oblong faces, topped by afros whose shape makes one think of the continent of Africa. We have to approach each of these three panels to understand that what is woven behind this series of faces so anonymized – and literally whitewashed in Untitled (Whiteout). Brewster transferred into these serial images some of the countless pages of the Ontario phonebook bearing the name Smith (the equivalent of Tremblay in Quebec). In this openly engaged series, Brewster states that she is “[making fun] of the notion of the monolithic Black community.” Indeed, the Smiths in the phonebook, like Black communities, do not form a whole from a single family, any more than they are identical or act in the same way. In other words, there are many ways of being Smith, just as there are many ways of being Black. In a long interview with Mohabir broadcast on YouTube,2 Brewster claims the right to opacity. This concept, introduced by creolization thinker Édouard Glissant, is available in Brewster’s works in which she rethinks Blackness between visibility and invisibility. In the end, the most effective response to the stigmatization of appearances is to be found in movement; as Mohabir notes, “In these continuing times of anti-Black racist violence, movement demands we remember that change begins with political movements.” Translated by Käthe Roth

1 Mona Hakim, « Serge Emmanuel Jongué, Capter et narrer l’indicible », Ciel variable, no 90, hiver 2012.

2 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cWUuhVRgczQ”>https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cWUuhVRgczQ

Érika Nimis is a photographer, historian of Africa, and associate professor in the Art History Department at the Université du Québec à Montréal. She is the author of three books, including Photographes d’Afrique de l’Ouest. L’expérience yoruba (2005). She contributes to various magazines and founded, with Marian Nur Goni, a blog devoted to photography in Africa: fotota. hypotheses.org/.

[ See the magazine for the complete article and more images : Ciel variable 117 – SHIFTED ]