[November 9, 2023]

By Pierre Dessureault

Although Jacques Payette’s paintings are well known, his photographs were relatively under wraps until the Musée d’art de Joliette, with the support of the Fondation Pierre Lassonde, published an impressive four-book set by John R. Porter. In Jacques Payette. Photographies, Payette immediately clarifies his position: “Photography is not my trade. I take photographs without pretentions, by pure instinct, to provide material for my graphic and pictorial production, to document my art career, and to record traces of my daily life.”

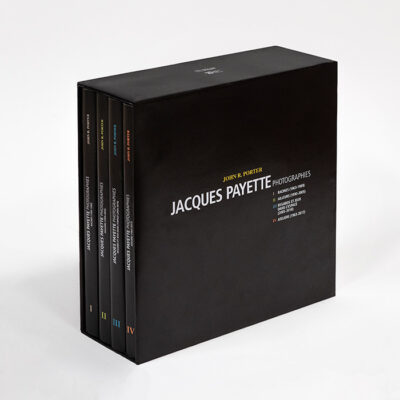

John R. Porter, Jacques Payette. Photographies, Musée d’art de Joliette, 2023, 27,9 x 27,9 cm, four hard-cover volumes in a sleeve, 924 pages (all volumes).

So, primarily, Payette’s photographic images become documents. He calls upon photography’s particular mimetic power to build a repertoire of personal subjects and motifs from which he will draw inspiration to produce a painting that exists purely through the qualities of its medium. Photography and painting are developed in parallel, each based on its own characteristics. In the former, the precision of the optical apparatus, the framing, the angles, and the points of view are obvious. In the latter, Payette replaces the spontaneous captures of the photographic medium with a space that he constructs and defines, imprinting his gestures on the pictorial matter, affirming that materiality is as an essential component of the painting as its iconography.

“Although I’ve regularly taken photographs with an eye to future paintings, I’ve mainly taken photographs to make photographs,” Payette says. Over the years, his photographic practice has diverged from his painted works. In turn, he addresses a variety of genres traditionally associated with a photography style that could be called direct and spontaneous. Porter’s chronological arrangement of his work emphasizes how his photographic style has evolved.

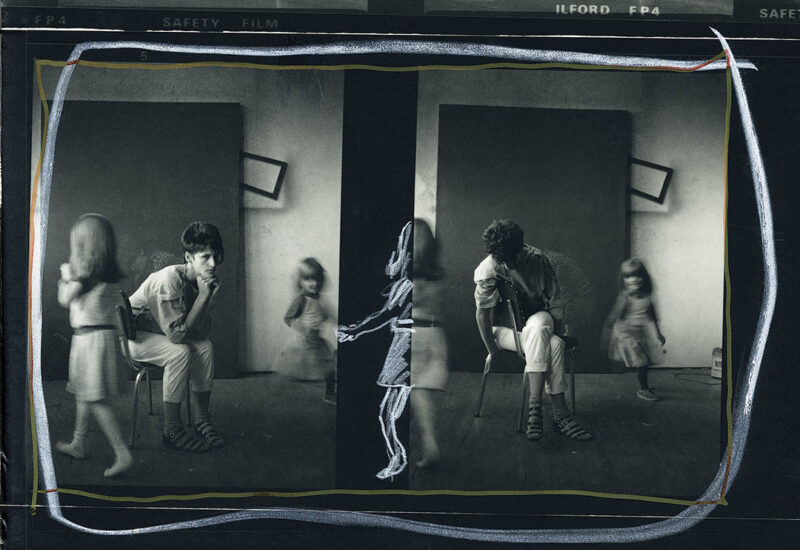

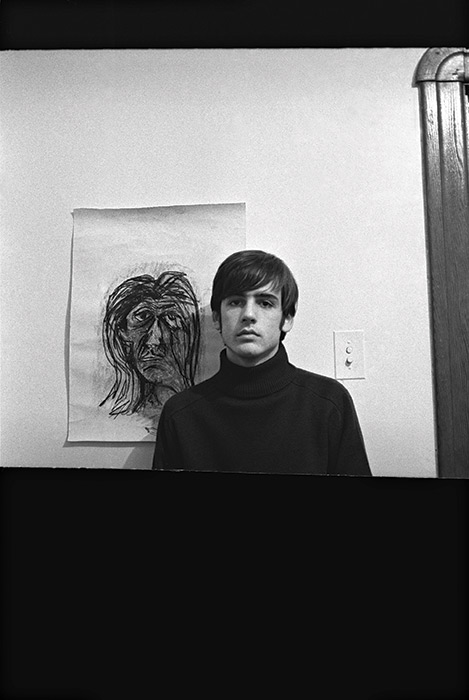

In the first volume, Racines (1963–1989), the visual story of a family and its daily surroundings is presented in moments caught on the fly and in an exploration of possibilities of describing both an environment and the expressive qualities of the medium. In the second, Ailleurs (1990–2005), Payette’s many trips give rise to snapshots in which his gaze falls upon structures of the social portrait and his point of view defines the image in truly photographic terms. The landscape makes its appearance, conveying a romantic feeling about nature in views that interweave forms, shadows, and light. Regards et jeux dans l’espace (2005–2018), the third volume, adds depth to the iconography of the intimate presented in the previous volumes and highlights some experiments with the expressive registers of the medium: a series of images made with a pinhole camera is reminiscent of the Pictorialists, who set out to bend the photographic image to the conventions of painting through multiple interventions on the surface of both negatives and prints. Payette employs none of these disguises: the blur and diffuse colours inherent to the process melt into the material of the image, affirming the singularity of the medium in its reading of the visible. In a completely different approach, two series, one on Greenland and the other on Guadeloupe, borrow a number of characteristics from classic documentary photography: frontality, primacy of description, optical precision. These views fix visual impressions retained for their forms, colours, and picturesque details, but they don’t form coherent groupings affirming a documentary intention and a perspective on their subject.

The last volume, devoted to various studios that Payette occupied between 1963 and 2007, takes us behind the creative scenes to the site of meditation and contemplation, labour and experimentation. Payette’s careful inventorying of his work spaces is more than an exploration of the iconography of the studio or an attempt to immortalize the fleeting moment of the imagination. It is, in a way, a portrait in absentia of Payette through his tools and works, through the traces that he left of his presence in these places. Photography becomes a tool to show what he has chosen to present of himself.

For an art historian, it is an important challenge to be the first to interpret a body of previously unknown photographic works produced by a painter with a well-established reputation. “Coming to understand, explain, and situate a secret garden was an irresistible challenge,” writes Porter, in a long preface. To begin with, there is a long history of friendship between Payette and Porter from which this book project arose. “In his openness to suggestions likely to improve the layout of his four volumes,” Porter continues, “we began a sustained dialogue, our exchanges soon resulting in corrections, the withdrawal and addition of photographs for a tighter and more complete selection, a strict respect for the chronological sequence of shots, the insertion of much information that was, in my opinion, essential, the adoption of a new general title and a subtitle for each volume, the writing of more precise captions and sometimes very substantial accompanying texts – up to two pages long! – for the photographs selected, and so on.”

Porter’s sympathetic approach places us at the heart of Payette’s work but also reveals its limits. It is difficult, upon reading the too-numerous texts that systematically accompany each photograph, to distinguish among an intimate knowledge of the artist, an in-depth comprehension of his approach as both a painter and a photographer, and a fair critical distance between the images and the discourse that one forms about them. This ends up drowning them in an interpretive excess that does not differentiate between the anecdotal and the essential. The images are born and live in a space of silence, and the meaning that they bear will emerge in their encounter with readers who, in a silent dialogue, will fully exercise their right to look at them. Translated by Käthe Roth

Pierre Dessureault is an expert on Quebec and Canadian photography. He has organized more than fifty exhibitions and has published books and articles on the subject.