[Fall 2008]

by Vincent Bonin

In 1967, Jack Chambers of London, Ontario, received a letter from the National Gallery of Canada informing him that its staff was beginning to assemble a bank of two thousand slides on Canadian art and asking for his permission to reproduce the image of one of his works.

He was notified that in the absence of a response, the institution would go forward without his authorization. Chambers expressed his refusal to collaborate with the gallery and sent a copy of his response to 130 Canadian artists.1 Following this dispute, he founded Canadian Artists Representation (CARFAC), whose demands were related mainly to the implementation of fair policies with regard to intellectual property. Sharing the aim of improving their economic conditions, some artists of Chambers’s generation articulated a different point of view on the notion of authorship and technical reproducibility. To make up for the absence of communications tools among their peers, they designed a platform for the exchange and dissemination of images through a non-market economy. This network began to take off with the emergence of the first artist-run centres, which also acted as information vehicles while short-circuiting the mediators’ (curators, critics) and institutions’ (commercial galleries, museums) legitimization mechanisms. Like the story behind the foundation of CARFAC, this group project found its point of origin in an individual experience.

When they founded Image Bank in Vancouver in 1969, Morris and Vincent Trasov2 hoped to evade the grip of commercial rights holders on the visual culture of the 1950s and 1960s.

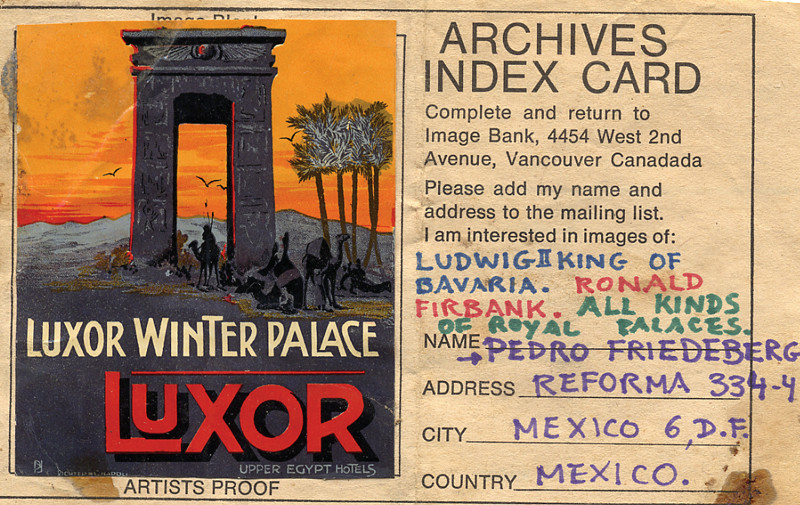

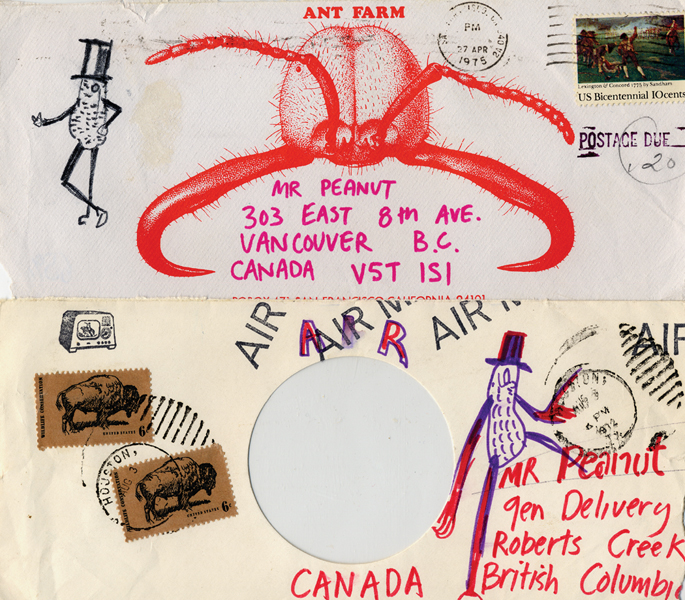

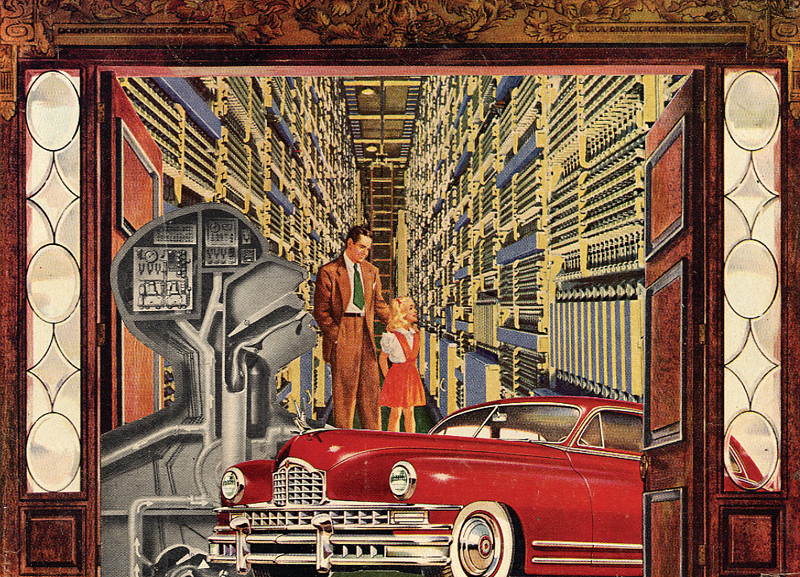

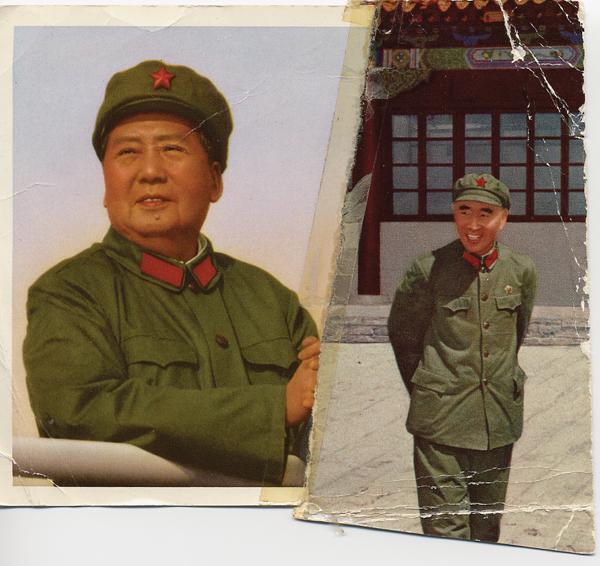

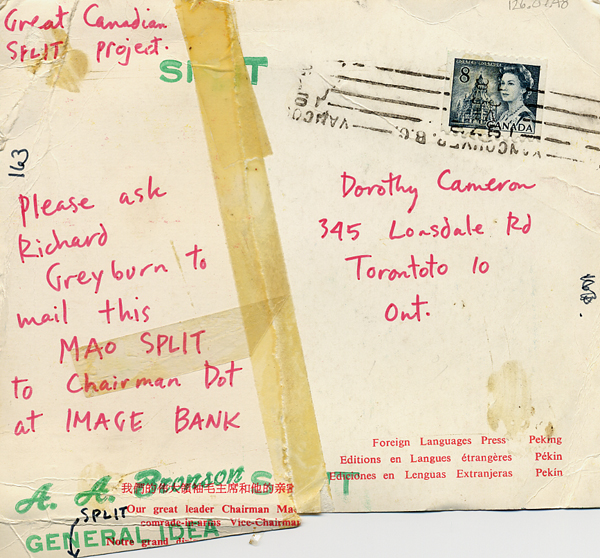

In the mid-1960s, Michael Morris was producing collages using content from copies of the American magazine Life. When they founded Image Bank in Vancouver in 1969, Morris and Vincent Trasov2 hoped to evade the grip of commercial rights holders on the visual culture of the 1950s and 1960s.3 Their project absorbed a number of the strategies used historical avant-gardes (Dada in particular) and Fluxus, but Ray Johnson was their main influence.4 Since 1962, Johnson had been sending collages to a group of peers, with the instruction to make changes to the missives and pass them on. He then created the New York Correspondance [sic] School with the purpose of giving form, both fictive and effective, to the methods of collaboration that he was encouraging. In an analogous way, Image Bank diverted the postal system as an ad hoc tool in order to crystallize a space of exchange beyond the range of the art field and media hegemony. 5 The tacit rule of cancelling out any intellectual property also encouraged the appropriation of statements made by others and multiplied role playing (use of pseudonyms, etc.).6

In 1970, Image Bank distributed an announcement with its first list of image requests. This was accompanied by a reproduction of a photograph of Nancy Berg, a 1950s model, decked out with the title “Image of the Month.”7

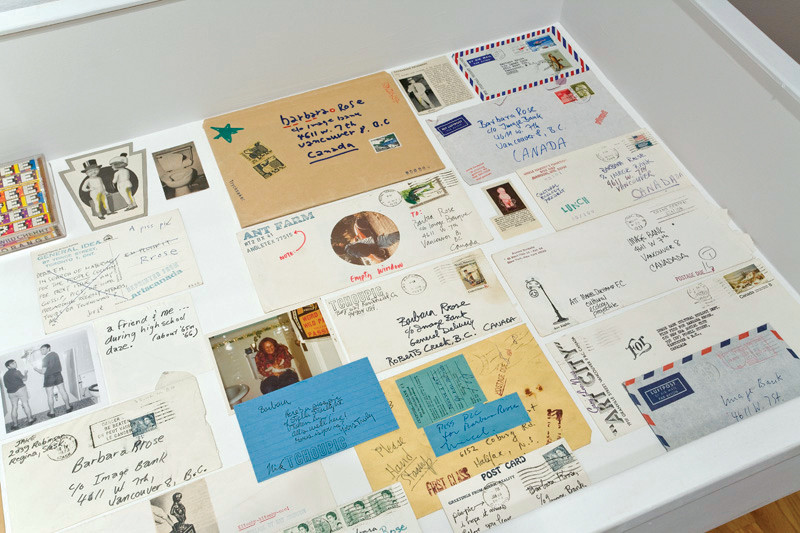

The following year, Image Bank asked correspondents in the network to send postcards for an exhibition organized by Alvin Balkin at the University of British Columbia Fine Arts Gallery in Vancouver. An edition of eighty postcards was published.

In 1972, Image Bank published a first version of an exhaustive alphabetical list of individuals listed, which conferred a tangible contour on the community of correspondents.8 This tool also included a selection of images gathered as a result of the requests. Its circulation snowballed, extending the network. As a corollary, the documentary mass of the Image Bank archive grew exponentially.

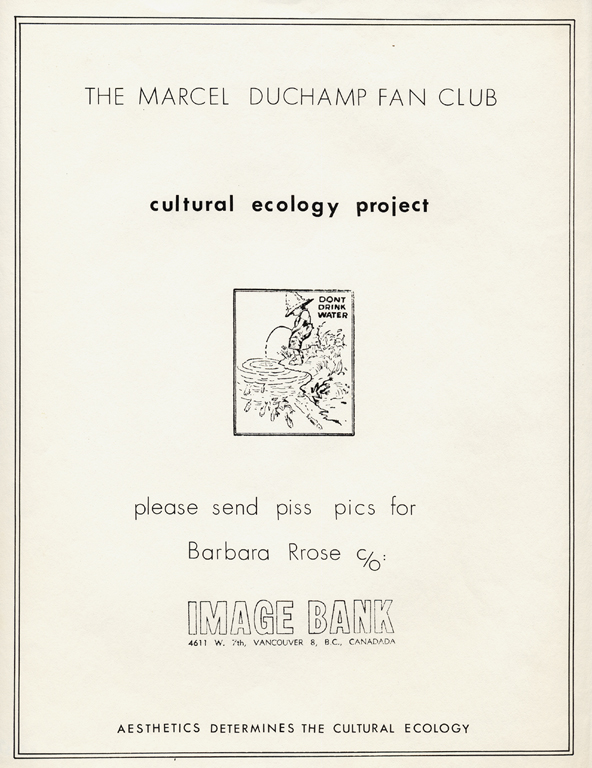

With its Cultural Ecology Project (1972), the collective asked correspondents in the network to send “piss pics” (images of urine) to the American critic Barbara Rrose (the modified spelling of her name is reminiscent of Rrose Sélavy, Marcel Duchamp’s alter ego). Predictably, certain recipients quoted Duchamp’s work and references to art history (manekenpis) in their responses. Others sent pornographic or scatological material that that tested the impermeability of the postal system as a tool of parallel communication.

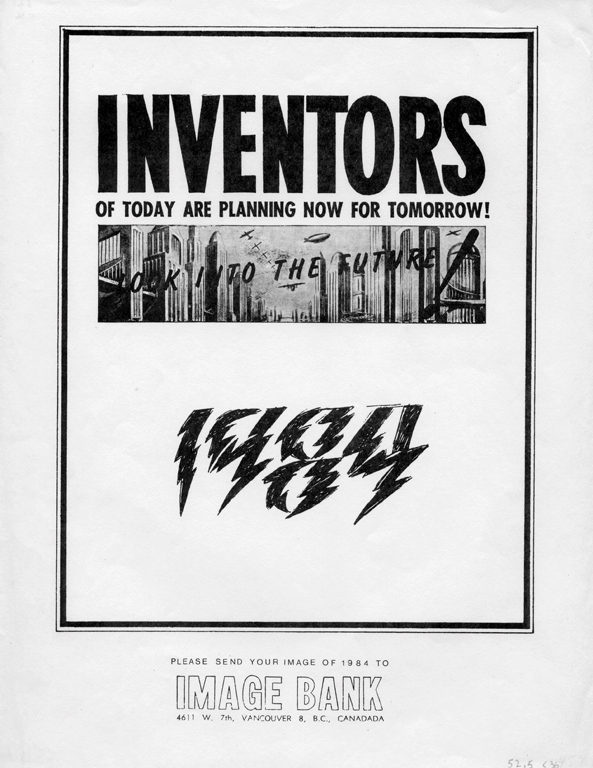

In contrast, the conservatism of another generation was studied by a project also produced in 1972. This time, Image Bank formulated the following instructions: “Inventors of today, prepare now for tomorrow: take a look at the future. Send your image of 1984 to Image Bank.” Taken from a variety of sources of the 1950s and 1960s – Life, Popular Science, and others – the images received evoked obsolete representations of progress and technology while highlighting the desires and fears of the period. Subsequently, these constellations of communal spaces became fertile ground for various collaborations within the network. Through a series of science fiction stories in the form of performances and spin-off products, General Idea of Toronto dreamed up a building whose construction was delayed until 1984. With its Time Capsule, the Californian collective Ant Farm stockpiled representative foods and medications of 1972 in a refrigerator sealed until 1984 (and finally opened in 2002).

In 1973, Glenn Lewis requisitioned everyday objects, various assemblages, and other objects. Presented in transparent display cases (each attributed by the participants to a year between 1620 and 1984), the missives received formed the structure titled Great Wall of 1984 at the National Research Council Library in Ottawa.9

The notion of counter-public is generally associated with discursive spaces inhabited by subordinate groups. Michael Warner specifies, however, that these groups absorb the protocols of hegemonic institutions when they create their own communication vehicles.10 In shaping such tools, Image Bank and General Idea extended their recycling enterprise to the logic of mechanisms that circulated information in capitalist society in the 1970s.11

The set of strategies employed by these collectives to administer the flow of correspondence represents a parody and reversal of existing bureaucratic structures (postal system, commercial image banks). Morris and Trasov considered the documents accumulated as a result of their exchanges to be symbolic capital that they could reinvest. In 1972, the summary of Image Bank’s activities since it was created took the form of an annual report.12 Like many collaborators (Dana Atchley, General Idea, Ant Farm, etc.), Trasov and Morris produced logos, a currency, letterhead, and stamps.

During the same period, General Idea appropriated the graphic template of Life to design the magazine File, the early issues of which distributed Image Bank’s lists.

The period between 1971 and 1974 was the heyday of these collaborative projects. In 1974, Willoughby Sharp, Lowell Darling, General Idea, and Image Bank organized the event Decca Dance: Art’s Birthday in Hollywood, California. The awards ceremony was a pretext for bringing together the individuals and artists’ collectives who had been communicating through the mail. It also marked the dissolution of this community as a counter-public.

In 1975, with the number of participants increasing, most of the members no longer responded regularly to missives. During this breathless period, Time Incorporated took the General Idea collective to court for illicit use of Life’s graphic template. In 1977, Image Bank presented its second exhibition of postcards and received a legal threat from an American company with the same name. These two lawsuits were explained by the media visibility enjoyed by the artists, who had become important players in the contemporary-art field. Unlike General Idea, which won its trial and published File until 1989, Image Bank backed down and adopted the name Morris/Trasov archive.13 The two artists considered their archive a work in evolution. Since the end of the 1960s, they had systematically preserved all the correspondence from their peers and formed a collection of publications on avant-garde movements after 1945. In 1974, they tried to inventory the content of this corpus using files similar to those that had enabled them to collect image requests.

After doing intensive cataloguing work during the 1990s, Morris and Trasov turned their archive over to the Morris and Helen Belkin Gallery in Vancouver. As Jacques Derrida notes, the acquisition of a private archive by an institution seals its dependency on the name of an individual or corporation.14 This signifier absorbs the “archives of others.” The bringing together of a number of interdependent corpuses, however, foils this domiciliation. What is created is a compromise structure among documents that are of varied provenances but linked by contiguous processes. The General Idea archive15 thus includes correspondence sent by Image Bank, while the Morris/Trasov archive contains missives received from General Idea. These two halves of an exchange have been brought together after the fact by researchers in the interstice between the address of their recipients and those of the institutions that are now their repositories. Like the image bank, this collage represents an unsituable discursive construction. By permitting these third parties to propose other accounts beyond the closing of their corpuses, the artists still recognize the conceptual dimension of the project within its material spin-offs.

Translated by Käthe Roth

The Marcel Duchamp Fan Club: Cultural Ecology Project. Please send Piss Pics for Barbara Rrose, 1972, Morris / Trasov Archive. Photo: Guy L’Heureux, avec la permission de / courtesy of Galerie Leonard & Bina Ellen, Université Concordia.

1 This event was discussed by Susan Alter Tateshi in “The House that Jack Built: Fifteen Years Later,” Carfac News, vol. 10, no.2 (Summer 1985), 2–3. 2 Up to 1972, Gary Lee Nova was also involved in the Image Bank’s activities.

3 Their name refers to occurrences of the motif of the image bank in books by Claude Lévi-Strauss and William S. Burroughs.

4 In 1970, Image Bank participated in the exhibition of the New York Correspondance [sic] School at the Whitney Museum of American Art. Concerned with establishing genealogies, some historians placed their work in the category of postal art. Yet Morris and Trasov (as well as Ray Johnson) rejected this movement, which they felt had been constructed after the fact by critics.

5 A close collaborator of Image Bank, Glenn Lewis created New York Corres Ponge Dance School of Vancouver, an informal cooperative structure modelled on Johnson’s New York Correspondance School, in 1970.

6 Vincent Trasov adopted the identity Mr. Peanut Planters, while Michael Morris used the pseudonyms Marcel Idea and Marcel Dot to correspond with his peers. This role play simultaneously extended to all members of the network.

7 For exhaustive accounts of the activities of Image Bank between 1969 and 1977, see Scott Watson (ed.), Hand of the Spirit: Documents of the Seventies from the Morris/Trasov Archive (Vancouver: UBC Fine Arts Gallery, 1992), and Luis Jacob (ed.), Golden Streams: Artists Collaborations and Exchange in the 1970s (Mississauga: Blackwood Gallery, University of Toronto at Mississauga, 2002).

8 International Image Exchange Directory (Vancouver: Talonbooks, 1972).

9 Aside from correspondence with peers, Image Bank took on a major research project on the limitations of formalist painting. During summer retreats in the countryside between 1972 and 1974, Morris and Trasov reproduced the entire colour spectrum on planks of wood in the format of commercial paint chips. Multiple configurations of these artefacts were then photographed and filmed in different landscapes, where they act as a cultural marker within a natural environment.

10 See Michael Warner, Publics and Counterpublics (New York: Zone Books, 2002).

11 I organized a three-part interdisciplinary project that investigated these questions, Protocoles documentaires, at the Leonard and Bina Ellen Gallery in Montreal. These exhibitions took place in 2007 and 2008. The publication will appear in 2009. For more information, see the gallery’s Web site: http://ellengallery.concordia.ca. See also AA Bronson, “The Humiliation of the Bureaucrat: Artists-Run Centers as Museums by Artists,” in AA Bronson and Peggy Gale (eds.), Museums by Artists (Toronto: Art Metropole, 1983), pp. 29–37.

12 Image Bank Annual Report (Intermedia Press, 1972).

13 Vincent Trasov and Michael Morris moved to Berlin in 1981.

14 Derrida chose as an example of such domiciliation of archives the transformation of Freud’s last home into a museum. See Jacques Derrida, Mal d’archives: une impression freudienne (Paris: Galilée, 1995), p. 13.

15 The General Idea archive and the Art Metropole collection are preserved at the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa.

Vincent Bonin is an artist and an independent curator. He lives and works in Montreal. Between 2001 and 2007, he was archivist for the Daniel Langlois Foundation for Art, Science and Technology. Recently, he mounted a two-part exhibition titled Documentary Protocols for the Leonard and Bina Ellen Gallery of Concordia University (Montreal).