By Pierre Rannou

Pierre Gonnord’s photographic portraits are fascinating for the experience that they offer us. The models gaze straight at the photographer’s lens, and we are taken aback: we feel like they are staring at us. This disconcerting sensation is due less to the meeting of our respective gazes than to the relationship of exchange that is surreptitiously created between them and us. Thus, our discomfort results in part from our sudden hesitation about what we would like to acknowledge in this impromptu relationship. If the intensity of the gazes aimed at us hardly encourages us to conceive of an intimate relationship with these unknown people, we have nevertheless already entered, in spite of ourselves, into a relationship of proximity. The framings not only give us to understand that there is some form of engagement between the photographer and his models, they also forcibly draw us closer to these models, to be symbolically within arm’s length. Now, the point is less for us to try to regain our distance than to look for what these photographic portraits are asking us to envisage.

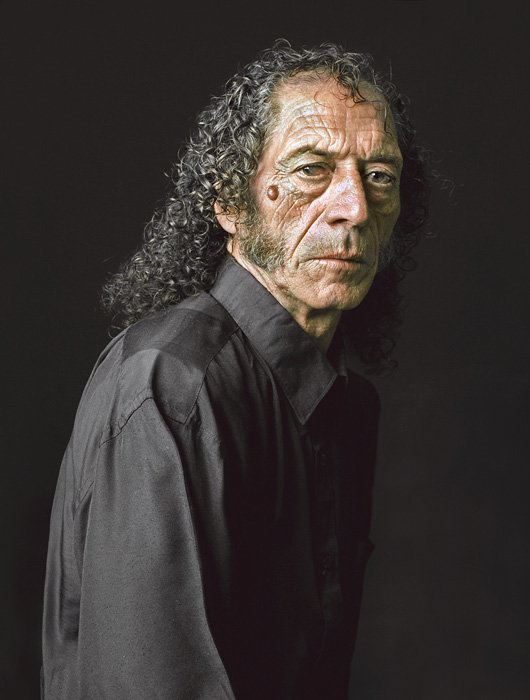

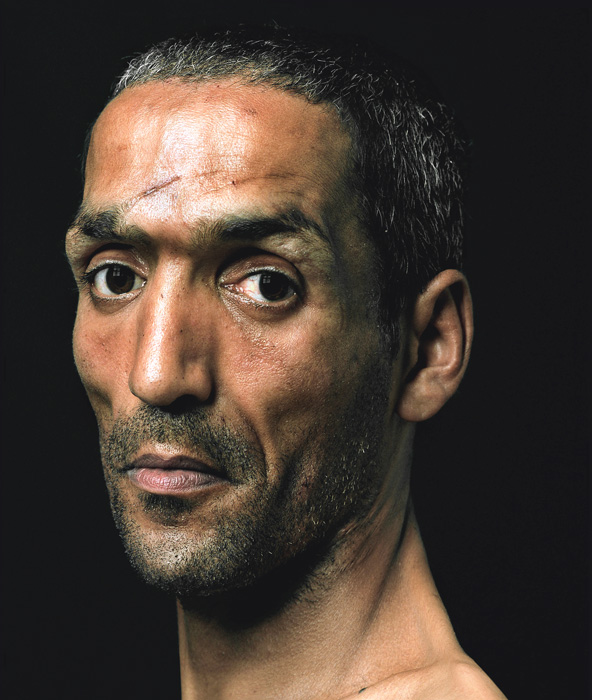

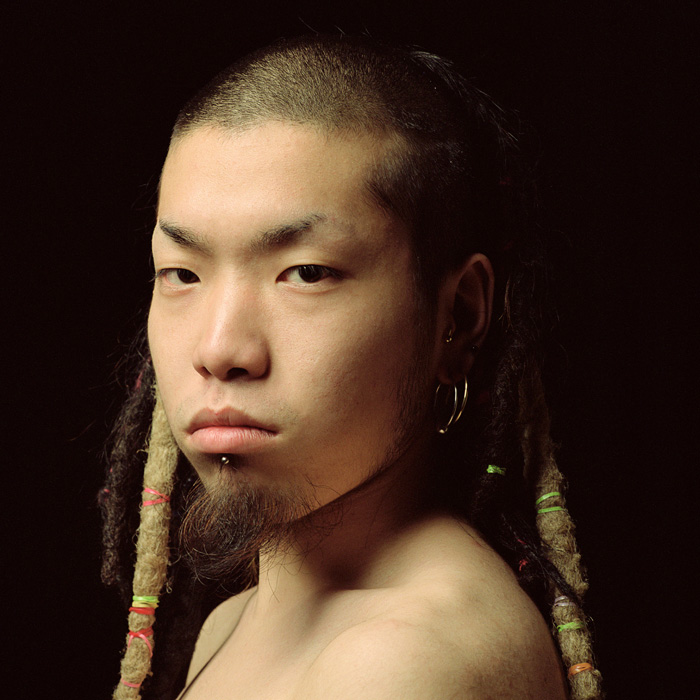

Although it proves difficult to observe any similarity between the models chosen by the photographer and his representation of them, our confrontation with these images forces us to recognize their kinship with Spanish and Dutch portraits painted during the Golden Age. This “family resemblance” may appear an effective way to ennoble the models – to give them a certain aura of prestige. Such enhancement is possible, however, only through the complete erasure of the site and setting in which these models are usually posed. In fact, these photographic portraits are the result of encounters between Gonnord and people who are labelled as fringe elements. In an interview with Luc Desbenoit for Télérama, the French-born photographer explained, “I’m hungry for encounters with people who are outside of or forgotten in society. I need them. They help me behave justly, without red herrings or hypocrisy. With them, there’s no point in cheating. You have to present yourself as you are, without false compassion, or they reject you. Especially the gypsies: they have the art of scratching your skin to see what’s underneath. If photography didn’t let me do that, I’d do something else.” 1 In his wanderings in urban centres and peripheries, Gonnord finds people with unique profiles, establishes contact with them, explains his artistic approach, and invites them to pose for him, either in his Madrid studio or in a small, improvised photography studio. And so, we have trouble understanding why he would want to deprive his models of their socio-cultural context and thus a part of their individual history, any more it would be conceivable for him to try to dress them up in a sort of formal mask, a persona in the Jungian sense – that is, a socially predefined character – in order to have them take a role in the game of social representations, even though this hypothesis is sufficiently seductive to make us want to sketch out interpretations of the portraits Attia (2010) and Maria (2006), for example.

In addition, keeping in mind that these portraits fit into series, such as the one on gypsies, of which the one called Konstantina (2007) is part, or the one on Galicia that includes Senen (2009), we have a better idea of the photographer’s concern with respecting and preserving the specificities of each model, even if the images retain few or no clues to their social status. And, aware of the risk he is taking in working with this pictorial aesthetic, for it could lead in the viewer’s mind to the idea of the isolation and exclusion of these marginal people from the public common space, Gonnord tries to avoid this pitfall by using their first names to title the photographs, thus establishing their identity and individuality for all to see.

Of course, this could simply be an exercise in style or a form of artistic dialogue undertaken with famous paintings and artists. There is probably a little of this in Gonnord’s approach, but without really trying to evade that issue, I prefer instead to think that he finds it an effective way to reaffirm that “every portrait is a representation,” to use François Soulages’s term.2 By importing old, proven modes of composition into the making of his portraits, the photographer may simply be taking advantage of our visual habits. Under these circumstances, it may be more appropriate to dwell on exposing and explaining the visual economy of these magnificent portraits to attempt to reveal the underlying motivations for borrowing this aesthetic model.

Looking more closely, we easily observe that the vast majority of Gonnord’s portraits have the models posed in a three-quarter position with the head slightly pivoted so that the face is turned toward the camera. Some framings are tight, whereas others give a bit of room for the models to breathe, although it’s impossible to draw any convincing conclusion from this. We would do better to pay attention to the backgrounds used in the making of these portraits, which are less neutral than they seem at first glance. They play the role of foil, highlighting and complementing the person placed in front of them. They push the subjects out into the spotlight, bringing them out of isolation by projecting them into the foreground of the image, while enabling the viewer to appropriate them in order to concentrate fully on their features. Similarly, it’s important to note that the light- ing, usually lateral and low-angled, highlights details and textures, giving the image a degree of richness. It bathes the models in shadow, favouring an intimate comprehension of the subjects.

By constructing most of his images in this way, Gonnord circumscribes the question of whether the poses are natural or staged. Furthermore, the systematic nature of the process gives us the idea that we are looking at a true visual family. The main interest of this arrangement developed by Gonnord resides in its capacity to create a perceptible abstraction of the people who participate in his adventure – a simplified image that never becomes a generic model. By not totally erasing their difference and giving them an image that will be judged worthy of attention, he engages us in admitting their value, in spite of ourselves, and adroitly instructs us to recognize their humanity. Thus, his photographic work appears to be a plea for social reconciliation with excluded people and outcasts. Today, the strategy of using a particular aesthetic model to make portraits of marginal people and outcasts in the manner of those of nobles and wealthy people of times past is clear and seems less ironic or cynical than what we might have otherwise thought, for it enables us to realize that treasures are within grasp and we simply have to reach out our hands to enjoy them fully.

Translated by Käthe Roth

2 François Soulages, Esthétique de la photographie. La perte et le reste (Paris: Nathan, “Nathan photographie” imprint, 1998), p. 61 (our translation).

Pierre Gonnord is a French photographer and portraitist, born in 1963, and now living in Spain. He spent some years in marketing and communications before developing a strong interest in photography. His work has received international recognition, with solo shows and acquisitions by major museums (in Madrid, Paris, and Chicago, among others) and several monographs and catalogues (the most recent being by La Fàbrica, Madrid, in 2013). Gonnord is represented by Juana de Aizpuru Gallery, Madrid, and Hasted Kraeutler Gallery, New York. www.pierregonnord.com

Pierre Rannou is an art critic and art historian who works as an exhibition curator. He has published essays in collected works and magazines and written several exhibition catalogues. He teaches in the Film and Communications Department and the Art History Department at Collège Édouard-Montpetit.