By Chuck Samuels

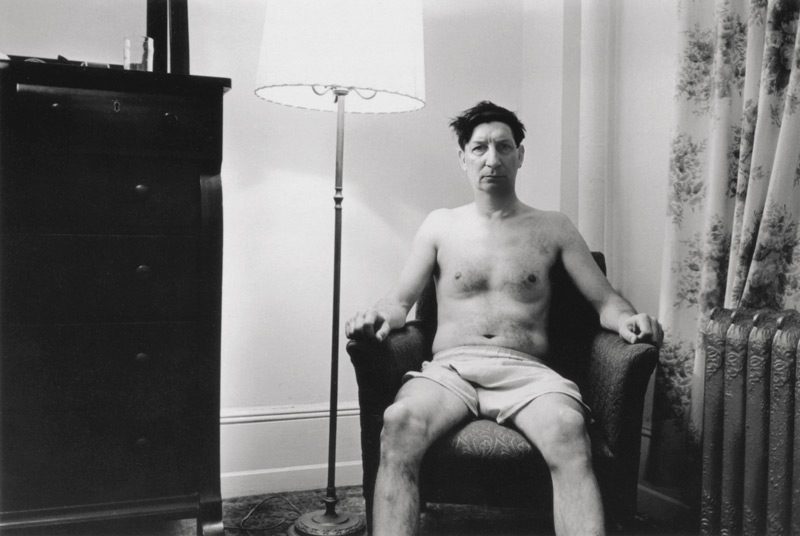

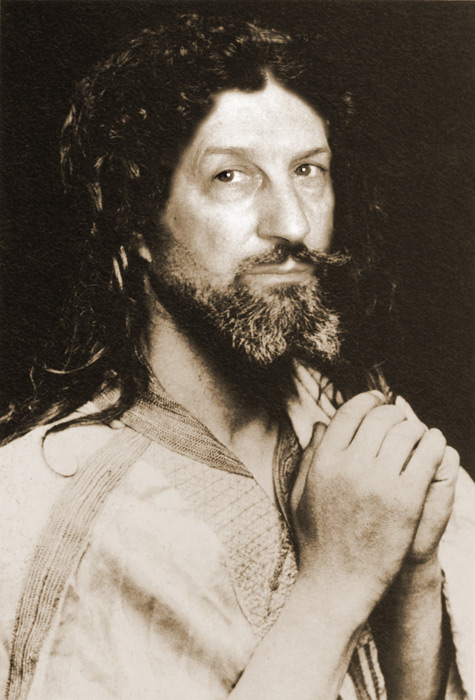

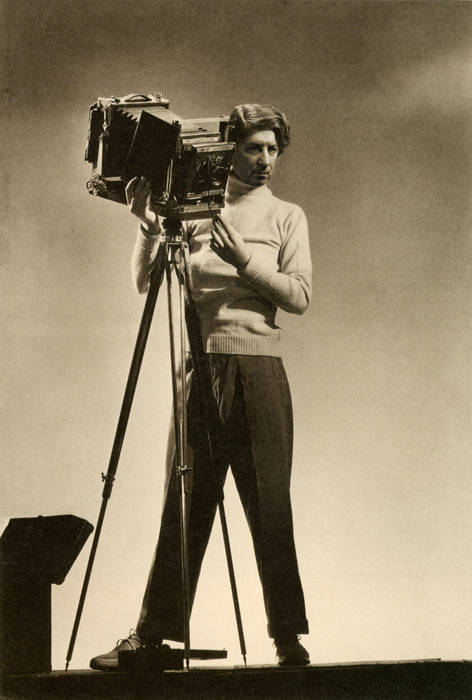

Chuck Samuels: In Before the Camera, you presented yourself in drag to look at the female nude in the history of photography; in Psychoanalysis, you appeared as both the Norman Bates and the Marion Crane characters; in Before Photography, you assumed the roles of photographers in film stills from a specific era; and now, with The Photographer, you are deploying a similar strategy with regard to the manner in which photographers have represented themselves in the history of the medium. Are you playing out a desire to become someone else, to become a star, to express a sort of narcissism, or to realize a particular fetish?

Chuck Samuels: First of all, I wasn’t in drag for Before the Camera; that would have had me dressing as a woman when, in fact, I was undressing as woman. Second, in Before Photography I wasn’t playing the roles of photographers, I was playing the roles of actors who were playing photographers. But to answer your question, whether or not I am narcissistic as a person may be arguable, but it’s not an element in my production as an artist. My work is not about fantasizing about characters or situations. Some people have thought it’s as if I’ve always fantasized about becoming Nastassja Kinski or Janet Leigh or James Stuart or Alfred Stieglitz. It is simply acting. In The Photographer, as in other works, I’m trying recreate, as earnestly and accurately as I can – including the quality of my performance – a pre-existing image. Or, if you will, by attempting to become the self-image of various photographers from the history of photography, I’m trying to become photography itself.

CS: What do you hope to achieve by “becoming photography”?

CS: When I’m in the midst of a project I’m not thinking about achieving anything specific; in fact the experience feels like becoming possessed by an idea, or a few ideas, and the ideas speak through me. It’s not exactly channelling a spirit, it’s more like I’m a ventriloquist’s dummy; my mouth opens but it’s not my voice you hear.

Later, when a project is finished and I’ve gained a certain critical distance, I can say with certainty that I’m trying to express and share my fascination with photography and its history with whomever is interested and perhaps with those who aren’t. I think it could be instructive for a number of reasons – certainly for artists who are engaged in the act of appropriation who think there is a larger story to tell.

CS: Performance is often a central element in your work. How did this come about?

CS: There is a funny history to that. As well as being a talented amateur photographer, in his younger days my father was a stage manager and occasional actor in the left-wing theatre. I myself was part of an experimental theatre group in the early 1970s, and we rehearsed in the basement of the Centaur theatre in Montreal that also housed Optica, an artist-run centre founded by William Ewing that, at the time, focused entirely on photography. I recall making a point of seeing a number of exhibitions during rehearsal breaks. So I suppose it is no accident that the two disciplines have somehow merged in my practice.

CS: I’m glad you brought up your father, because this brings us back to issues that we discussed in our last interview – specifically, the autobiographical aspect of your work. Despite your claims to the contrary, one finds visual clues in a number of your projects and in things that you have written over the years that indicate a strong autobiographical inclination to your various projects. Do I sniff the faint odour of nostalgia?

CS: I will maintain that, at least from my perspective, my work is not particularly autobiographical. But, at the same time, my projects frequently emerge from my personal history with the history of photography. In the different projects I’m trying to develop different ideas, different arguments, but finally the heart, the quintessential, remains this questioning of the photographic truth.

CS: You seem to have evaded the question.

CS: I’m not sure nostalgia is the most appropriate term, but it’s quite true that my work explicitly deals with memory and seeks to stimulate the viewer’s memory in order to be most effective. At the same time, I’m considering photographic traditions that, when I was a younger and possibly more naïve artist, seemed so natural. So comforting. So true. Perhaps that acrid smell is nothing more than the loss of innocence.

CS: Before the Camera dates from 1991, Psychoanalysis from 1996, Before Photography from 2010, and now, in 2015, you are bringing out The Photographer. Why the long gaps between projects?

CS: First, I have worked on a number of other projects, including the MOVIE/MUSIC video cycle with Bill Parsons, InSiteOut with Sylvie Cotton, and Dans l’œil de l’autre with Gabor Szilasi, between the ones you mentioned. But I’ve also had additional duties: from my first exhibition in 1980 until very recently, I have always had a full-time job. Each of these jobs was related to photography (photography teacher, sales-person in a photography store, medical photographer, supervisor of a hospital’s audio-visual department, and director of a photography event). And for a number of years I was a half-time single parent. While I have absolutely no regrets, it’s true that all these responsibilities have slowed down my production. But I always continued my personal photography, because that was always the most important thing. Also, many of my projects required extensive reflection and research. You see, I’m a perfectionist. If I take a picture from the history of photography or the history of cinema, it’s got to be good.

CS: The camera is included in surprisingly few of the self-portraits that you chose to remake, but the inclusion of the camera is often the hallmark of a self-portrait. What are your criteria for selecting the images to remake?

CS: I chose among the many self-portraits that had an impact on me as I was growing up and studying photography. So, an essential element of The Photographer is memory. My memory. And the viewer’s memory. When I had completed the research I had many more potential images to work with, many of which featured cameras, but I finally reduced it to roughly twenty-five photographs and a short video.

The ritual of the photographic self-portrait is performed before the camera often with the aid of a mirror, so that the camera is sometimes rendered visible in the resulting image. You, yourself, pointed out in our last interview that over the years, the camera, as both object and subject, has figured more and more prominently in my work. Most people see the camera as an objectifying instrument. Well, I think that is complete nonsense. The camera is not objectifying instrument; it is a recording instrument. In the video component of The Photographer I’m recording the camera in the context of recordings of different photographers discussing their work.

CS: How do you respond to those who comment that all of your projects resemble each other?

CS: More or less the same way I respond to those who complain when I produce a project that doesn’t resemble the others: the only honest way is to not care what people think. You have to believe in what you’re doing and do it, and if people get it, they get it. If they don’t – it’s up to them. I don’t care. I don’t care because I make the work first for myself and finally for myself and for my own needs.

Chuck Samuels is an occasional freelance critic who lives and works in Montreal. His most recent article published was a previous interview with Chuck Samuels titled “The Figure of the Photographer,” which appeared in the Winter 2011 issue of Ciel variable (No. 87). He has also published articles in such Canadian contemporary arts magazines as MIX, Fuse, and Vanguard (co-written with Moira Egan). Samuels contributed a chapter to Women and Men: Interdisciplinary Readings on Gender, edited by Greta Hofmann-Nemiroff (Fitzhenry & Whiteside, 1987)

Since 1980 Chuck Samuels’s photographs have been exhibited, published, and collected extensively in Quebec, Canada, and abroad. His installation and video works have been presented in various venues, including several Canadian film and video festivals, and his photographs are in numerous public and private collections in Canada, France, Belgium, and the United States. The Photographer, his most recent project, will be presented at Galerie Le Réverbère in Lyon in May 2015. Chuck Samuels lives and works in Montreal.