[Spring 1997]

by Céline Mayrand

To escape the unbearable feeling of powerlessness to which her human limitations confine her, Anne Arden McDonald exceeds them. She imagines herself free to float and breathe in the water and to fly in the air.

For this young artist-photographer, self-representation quickly imposed itself as a necessity; even when she was in her teens, this practice provided an ideal refuge in which she could extend her field of investigation of dreams. To slip away from an immutable terrestrial attachment, she found this place of seclusion where she could run free. And thus she began an outpouring of dreams in real life . . .

“The photograph states that the subject is the site, can become the site of an internal transformation that will make it not transparent, but offered to view.”1

Given the many efforts deployed to communicate that which, in spite of itself, the subconscious would like to express, one forgets the falseness of the premise of “mise en scène” photography. This is the subjective vision of a world that fits into an oneiric space, a stunningly solitary universe in which the desire to represent oneself to oneself is a divine obscenity. It is that which openly, and without modesty, offers itself to view and, through this very fact, is disarming.

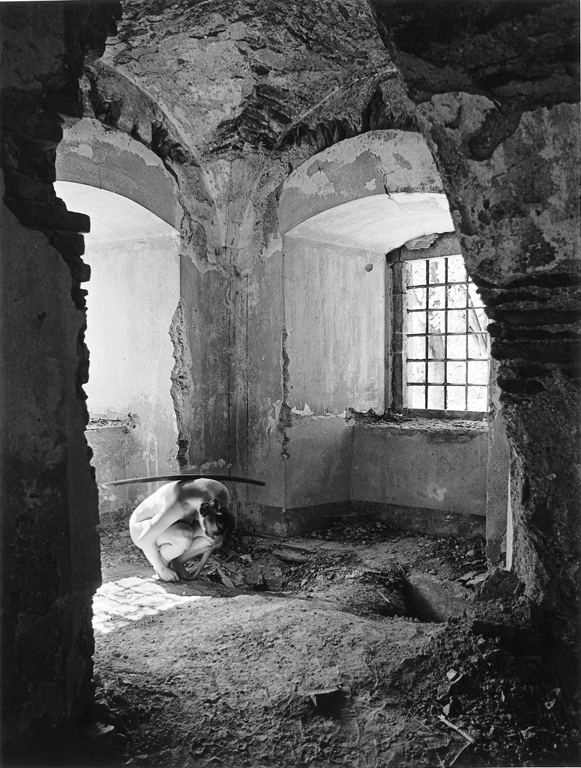

Thus, here is an expressionistic photography with a poetic flavour in which use of chiaroscuro consigns all immateriality of dreams to the images. The expressive use of light seeks to capture the unique mystery in which dreams so deliciously envelop themselves. For all their extreme precision, these black-and-white photographs are imbued with a disturbing lyricism that seeks to evoke the ecstasy that is both distressing and dramatic in the very idea of their production. Each photograph provokes a sublime sensation in the viewer that might be called exquisite pain – for each photograph reiterates, in its own way, the philosophical certainty that truth appears only in the light of death.

What is seen here as the impulse behind an intimate gesture moves spontaneously from the depths to the surface, from the unconscious to the conscious. “The subject of consciousness is attached to this effect of meaning, and capturing it as an image, as a setting of characters in a dream, is itself included in the scenario, or better, includes its own body.”2 Captured and trapped, the meaning offered by the subject to the viewer, and to the light, is first deposited in a darkroom. And, to be revealed, the invisible memory is deposited in the very filter through which it is poured. Only the essence of the experience, detached from the mnemonic procedure, is retained. One might say of the photographic sign that it occurs as much as a residue as an involuntary anamnesis – a memory in which the meaning is deliberately, if not unconsciously, lost. In photography, it is through its very adherence to the support that, in spite of itself, the meaning adopts the status of a sign. The unconscious is to the conscious what the camera obscura is to the photographic support. Thus, it may be said to be the perfect mechanism for phantasmagoric projections.

What parades before our eyes is deployed in a mythic space: a sort of non-place, a world that lends itself to all the imaginary reconstructions in which a woman who is both bird and fish evolves according to her own desires. Within this chimerical schema, Anne Arden McDonald adopts sometimes the skin of an angel, sometimes that of a siren or other nymphs who take on hieratic attitudes and play out their respective fates. For example, in the ruins of a temple hall, we witness the fatal consequences of Icarus’s fall; his feathers have been scattered by his passage (a passage to death) through the ceiling. The submissiveness of attachment to the earth is evoked in this image, where the artist represents herself bound and immobilized in the centre of a room shot through with light. In some works, such as the one where she offers herself as a sacrifice to a god of fire who encircles her, the evocation of the ritual gesture transgresses the sacredness that intrinsically confers its spiritual dimension upon all of these photographs. In another image, she swims against the current, a siren struggling to mount the waterfall to join a floating Ophelia, who is sleeping or perhaps already dead. The ascent toward the ultimate and the anguish underlying such an attempt are unbearable. The feelings of loss of consciousness and abandonment to dream are suggested in the “distraught” wandering of an exiled sleepwalker on the rampart of a sumptuous yet austere citadel. The flight through rapture is a paroxysm while a muse dances the Sabbath in a fern-flooded undergrowth near a shore.

For McDonald, dreams and reality merge, rather than splitting apart, for, if she was unable to take the key to the fields away with her, she traded it for the key to dreams. She shows that it is impossible to exhaust dreams, and her quest, although exultant, conceals something infinitely pathetic within her. The beauty of such sincerity, which expresses itself naturally in the oneiric exodus, recalls somewhat Pascal’s famous words to the effect that life is but a dream from which we awake only when we die. On the other hand, perhaps it is an invitation to flee into dreams. All we have to do as imagine ourselves as amphibians, men and women, as creatures in a dream . . .

Translated by Käthe Roth

1 Danièle Sallenave, «Le corps imaginaire de la photographie», Le Corps et ses fictions, Paris, Minuit, coll. «Arguments», 1983, p. 95.2 Serge Leclaire, Démasquer le réel, Paris, Seuil, 1971, p. 112.

Born in London in 1966, McDonald now lives and works in New York. Since 1988, her works have been shown all over the United States and in a number of European cities.

Céline Mayrand lives and works in Montreal, where she runs Galerie d’art Lavalin. An art critic, she has written many articles and essays, and she contributes to various contemporary-art magazines. A research assistant for Mois de la Photo à Montréal in 1997, she is currently working as an independent curator.