[November 23, 2021]

By Louis Perreault

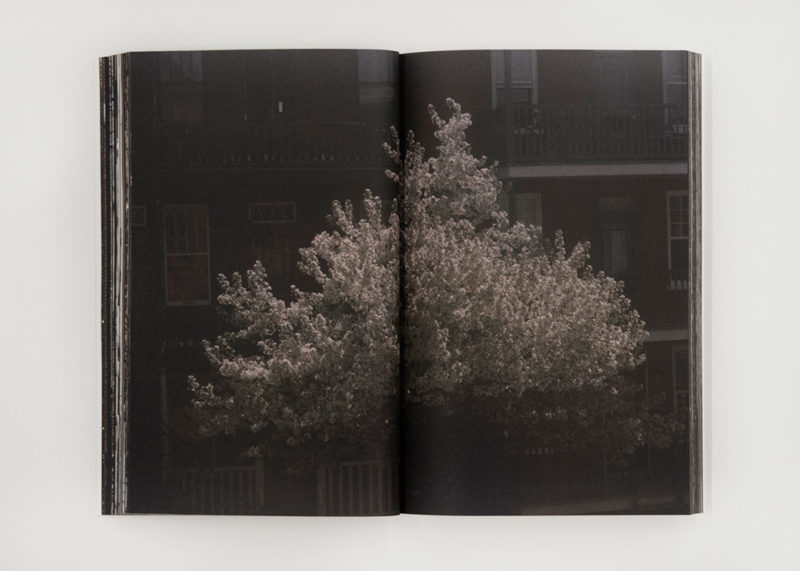

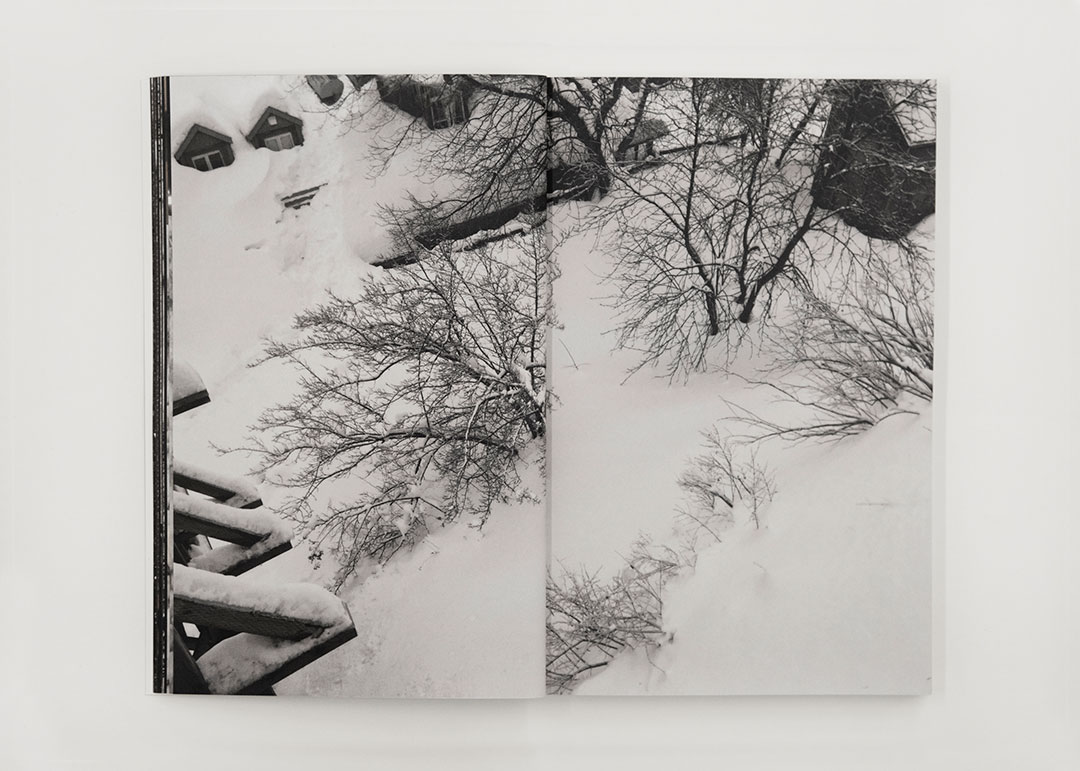

Stretching out on the black asphalt are rays of hard light that have pierced through the foliage of a white ash tree. Farther on, cobblestones, aged by several hundred years of foot, car, and horse traffic, suggest an old American city, which is not named. Ice, snow, and, especially, wild grape and other invasive species proliferate, freed from all forms of control and answering only to their own conquering imperatives. They are the symbols of a life that has never been muzzled and is always in perpetual motion. At the heart of these spaces slowly walks a woman who recognizes, in today’s brick and milkweed, long-ago days.

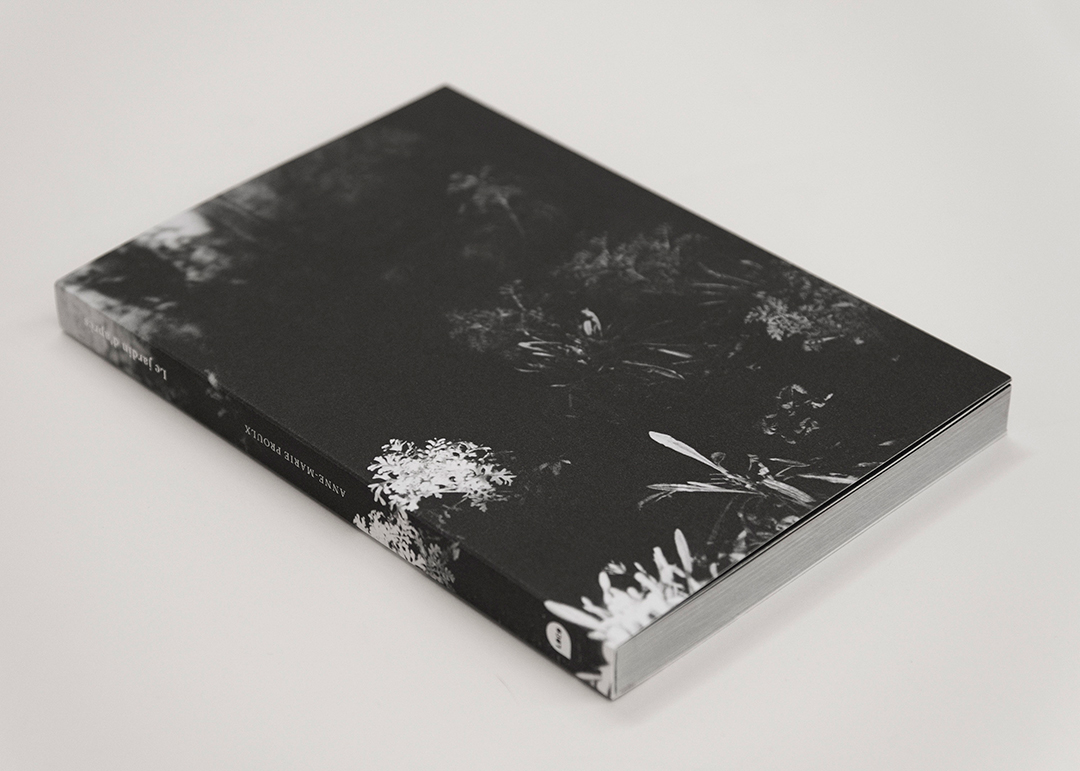

“Plunging” seems to be the verb that best fits the reading experience offered by Anne-Marie Proulx in Le jardin d’après1.The images in the book, like the digitized texts sprinkled throughout, compel us to enter the history and memory of the place, where literature and imagination intermingle. From page to page, it seems, the surface disappears above our heads and silence overtakes us, as if we are literally plunging into watery depths.

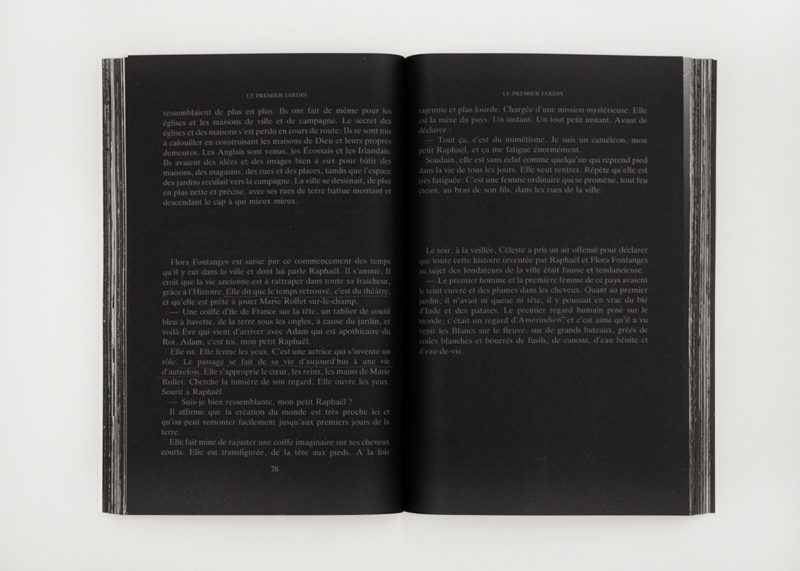

First, there is the city, which we discover through details. Plants are part of every nook and cranny, building a vast urban garden composed of wild flora left to itself. Then, inserted into the series of photographs, bits of text appear on digitized images of blank pages, from which Proulx has deliberately erased all surrounding textual context. All that remains are statements and questions formulated with “I,” giving the story an intimate, personal dimension. As the title suggests, these sentences are linked to Anne Hébert’s book Le premier jardin. A reference list at the end of the book informs us that these are excerpts from various plays, which a reader familiar with Le premier jardin would recognize as having been evoked by its protagonist, Flora Fontanges. By embedding these references, which make each detail in the book a reflection on what comes before people and things, Proulx composes a work that is decoded and discovered in details shining with mystery.

At the centre of the book, Proulx inserts a five-page excerpt from Hébert’s novel. This passage suddenly clarifies the book’s rather atmospheric offering: Flora Fontanges recalls the story of the first garden in the city, which was cultivated by Marie Rollet, the first European woman – with her husband, Louis Hébert – to settle in New France. After telling herself that “every story in the world has begun again because of a man and a woman established in new soil,” another character in the novel, Céleste, comes to remind both of them that this first garden, on which their reverie is unleashed, was in fact planted on First Nations land. Thus, the genesis of a history is ever more profound, more complex, and inhabited by the experience of people we don’t know. By borrowing from the multilayered novel that is Le premier jardin, Proulx pursues her research and leads readers ever deeper into the possibilities of a reading of history. She sensitively succeeds in plunging us into a poetic fiction, shaped by memories and constructed on the unstable ground of memory. In this rich work, the book form only further strengthens the intimate and subliminal experience. Translated by Käthe Roth

Louis Perreault lives and works in Montreal. His practice is deployed within his personal photographic projects and in publishing projects to which he contributes through Éditions du Renard, which he founded in 2012. He teaches photography at Cégep André-Laurendeau and is a regular contributor to Ciel variable, for which he reviews recently published photobooks.