[November 16, 2022]

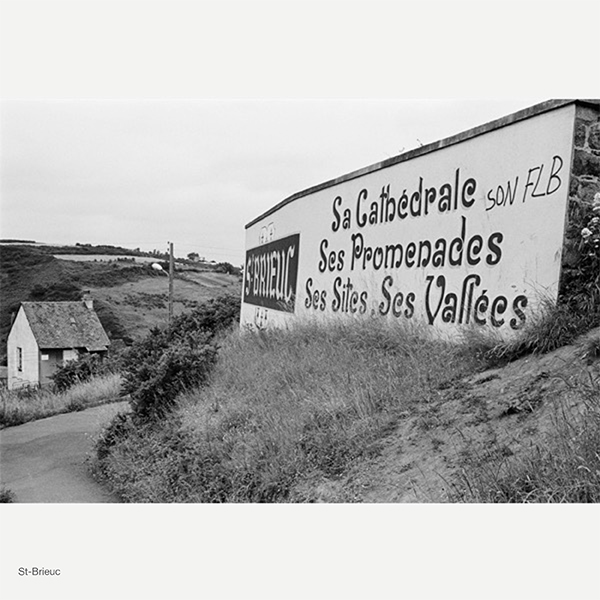

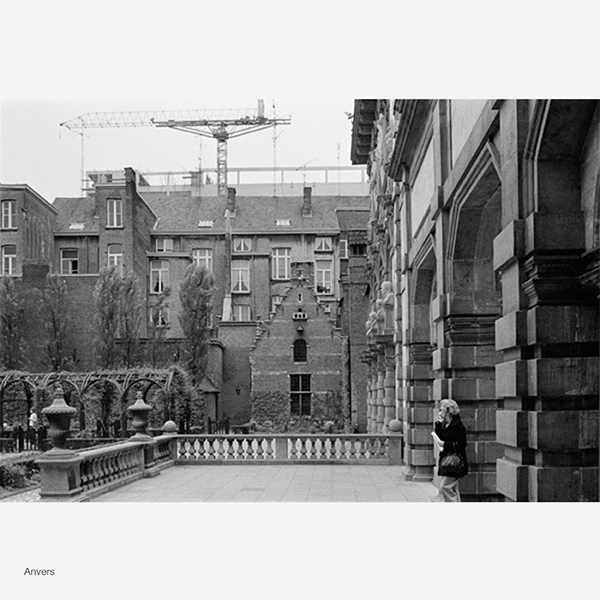

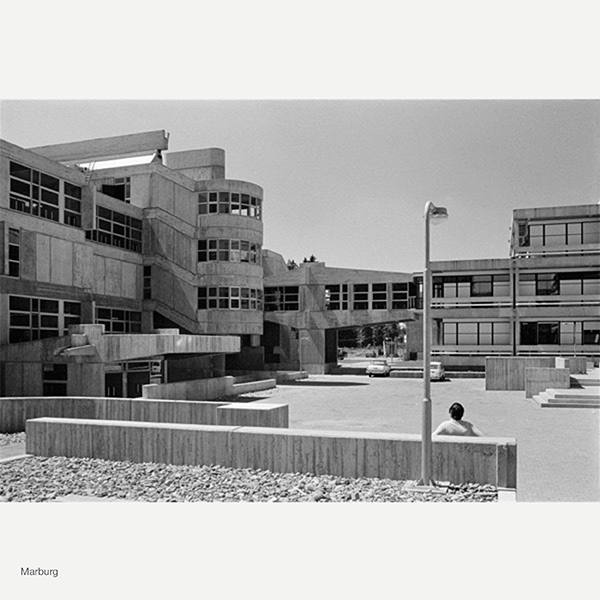

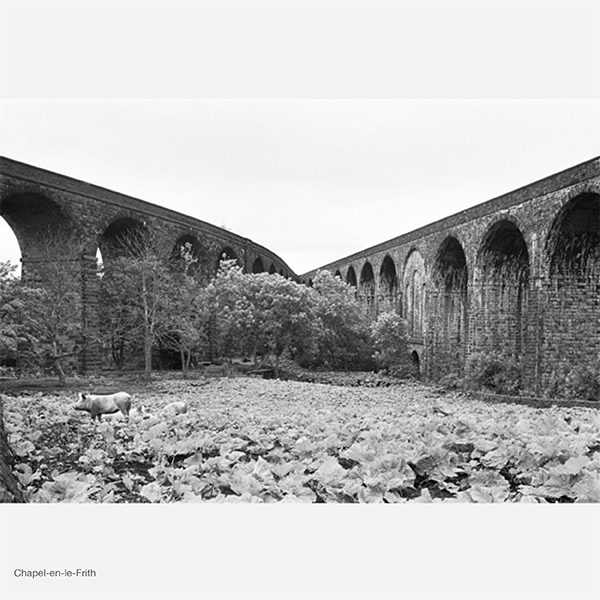

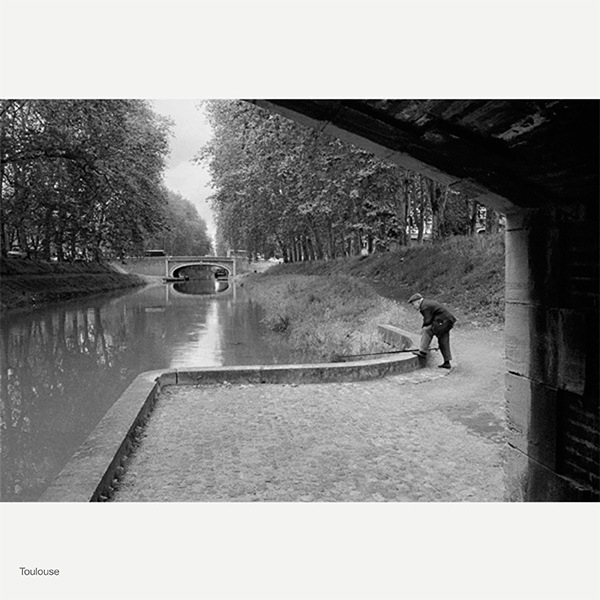

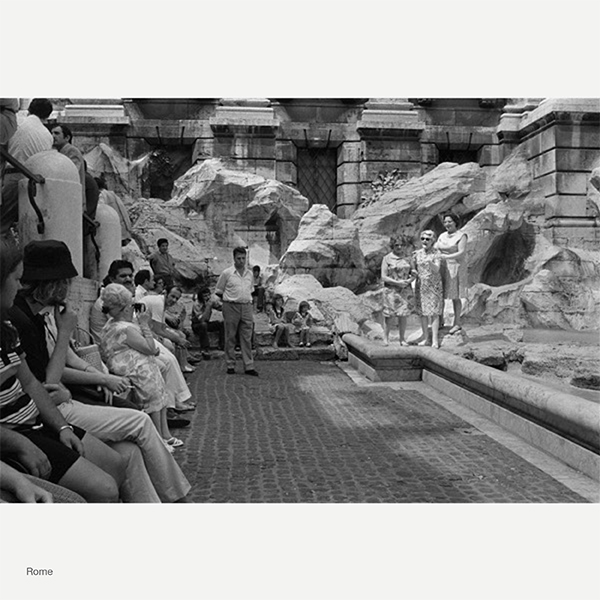

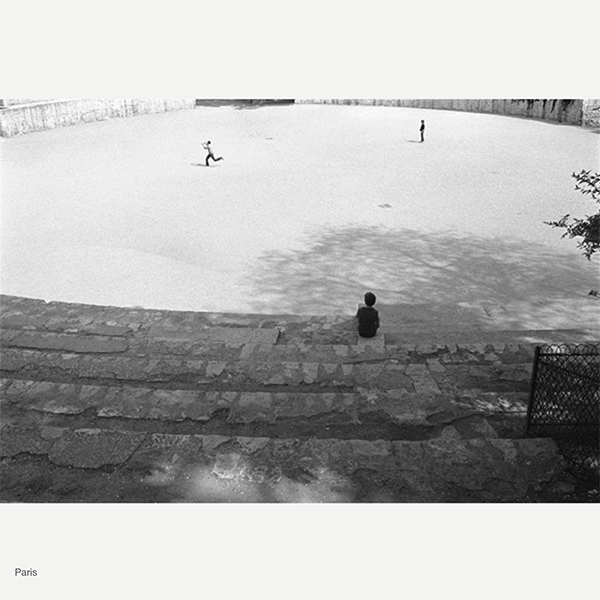

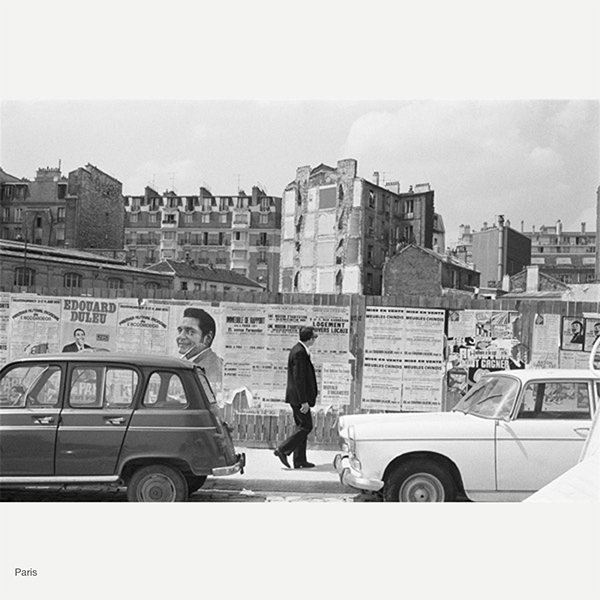

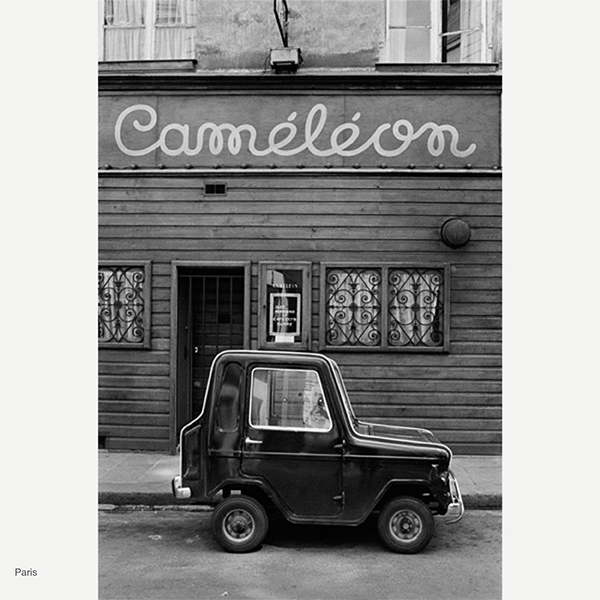

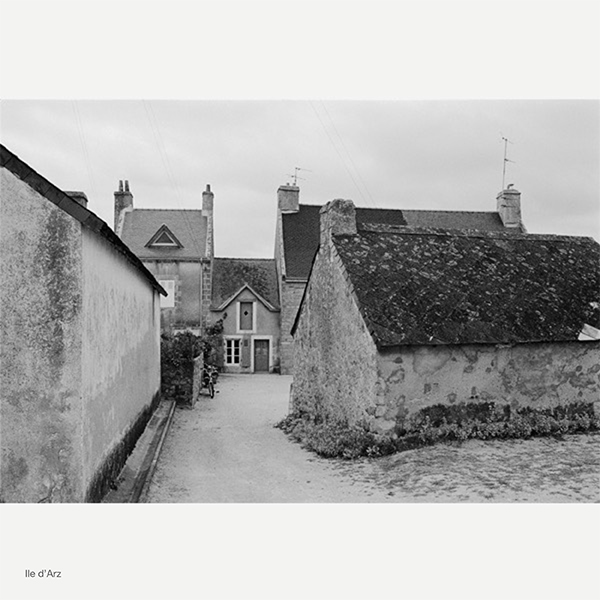

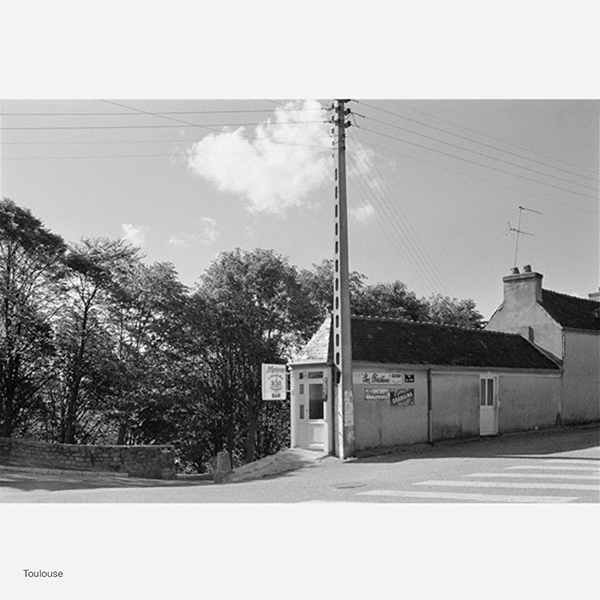

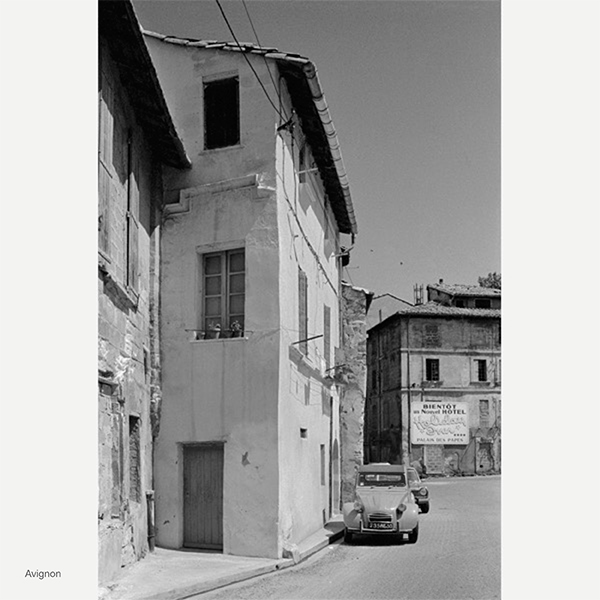

Brian Merrett has taken a deep dive into his early years of practice, and here he presents photographs taken in 1972, during his “grand tour” of Europe. This formative trip consolidated his activist’s eye and his interest in architectural heritage, which he had developed in Montreal and which would endure throughout his career.

By Brian Merrett

The noise, smells, roughness, and potential of construction sites were familiar to me as a child, but, when I was seven or eight years old and being driven home from a piano lesson, my architect father stopped the car in a driveway on the campus of MacDonald College in Sainte-Anne-de-Bellevue, Quebec. He asked me to step out of the car, positioned me in the middle of the small road, pointed me in the right direction, and, standing behind me, put his hands on my shoulders.

“Look across the football field at the building over there and tell me how many cupolas you see,” he said. I guess he had taught me what a cupola was.

“One,” was my answer.

“OK, come over here and tell me again,” Dad instructed, moving me over to the far side of the road.

“Two,” I replied, seeing another cupola, partially hidden, on the building behind the first one I had seen.

“That’s called alignment,” he said, and we got back in the car and left.

In our 1950s Modernist home, a house whose driveway the local taxi driver wouldn’t enter and that the neighbour’s kids called “The Three Boxes,” Dad took me to his draughting table and sketched the layout of the campus, drawing the axis of the buildings. Composition and the alignment of sight-lines have been strengths of mine ever since.

In 1969, at the end of my apprenticeship, I documented the restoration of a nineteenth-century bank façade in Old Montreal and used my vantage point on a scaffold to turn and capture a view of Place d’Armes. That single photograph showed two of Montreal’s oldest buildings, dramatically confronted by a mammoth 1960s glass-and-steel office building. It didn’t fit the vocabulary, and one might wonder who at city hall handed out the building permit. I like to believe that this image was the beginning of an awareness of harmony in urban landscapes and the need to preserve historic buildings.

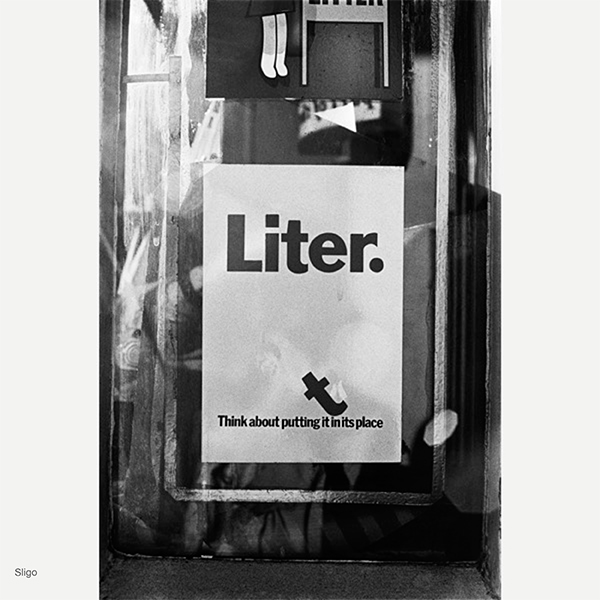

That led to my becoming active with environmental and architectural preservation groups in Montreal. In 1969 and 1970, as the publicity director for the Society to Overcome Pollution, I designed and built a fifteen-foot geodesic structure that we called the EcoDome. I decorated it with triangular photographs on environmental topics, and we would set it up in shopping malls and hand out brochures. In early 1972, I was approached by Friends of Windsor Station to provide images for their campaign to save the station and, between 1969 and 1972, the Westmount Action Committee used a number of my images in their campaign to protest – then document – the construction of the Ville Marie Expressway through lower Westmount and Little Burgundy.

In 1972 and 1973, after my own street was turned into a highway exit route, leaving me without a place to park, my monthly visits to the nuns’ residence where my car then lived led me to produce photographic documentation that ultimately prevented the demolition of Shaughnessy House, which has since been repurposed as part of the Canadian Centre for Architecture. That led to my becoming active with Save Montreal and, in 1975, I was asked to be on the founding board of Heritage Montreal. Many photographs of both threatened and preserved buildings were prepared for both organizations.

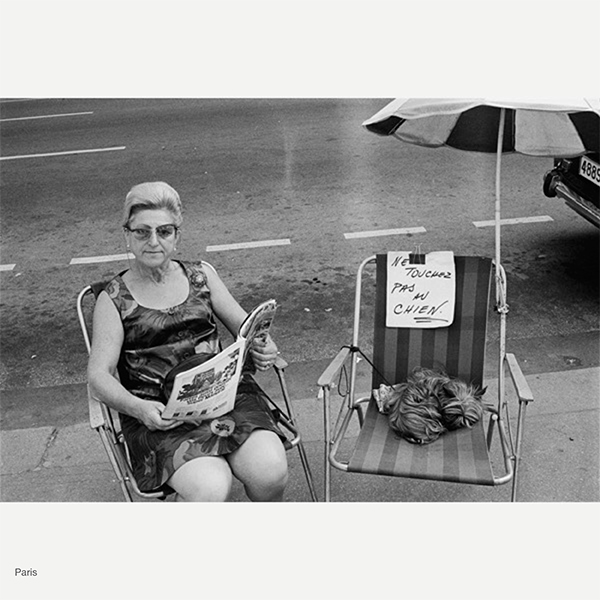

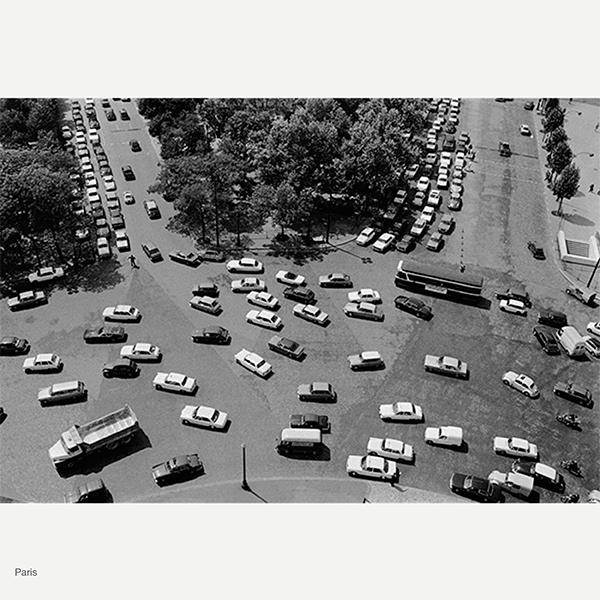

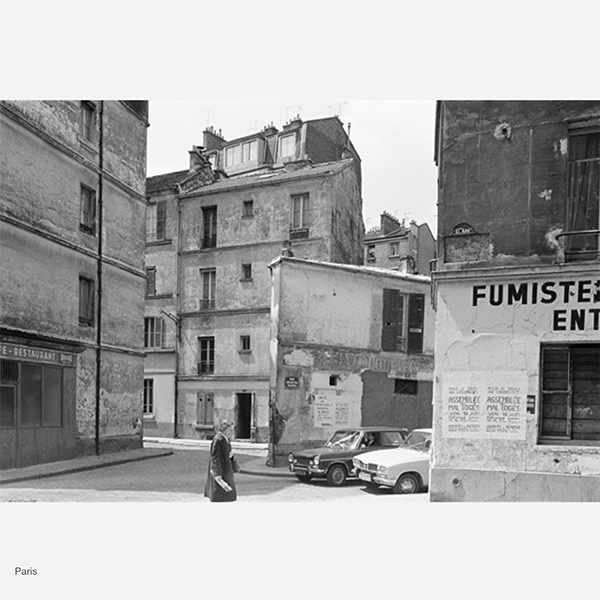

From the beginning, part of my passion was watching the dehumanizing of urban spaces by the automobile. Beginning perhaps with the Drapeau administration, downtown Montreal had been taken over by widening streets and ever-expanding parking lots, and a walk down just about any street in the city core brought vistas of vast open spaces filled with cars. Inevitably, the camera would come up and some commentary would be made.

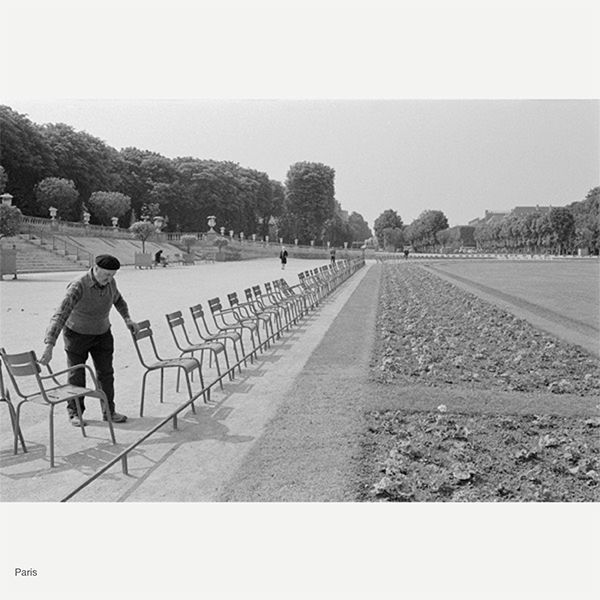

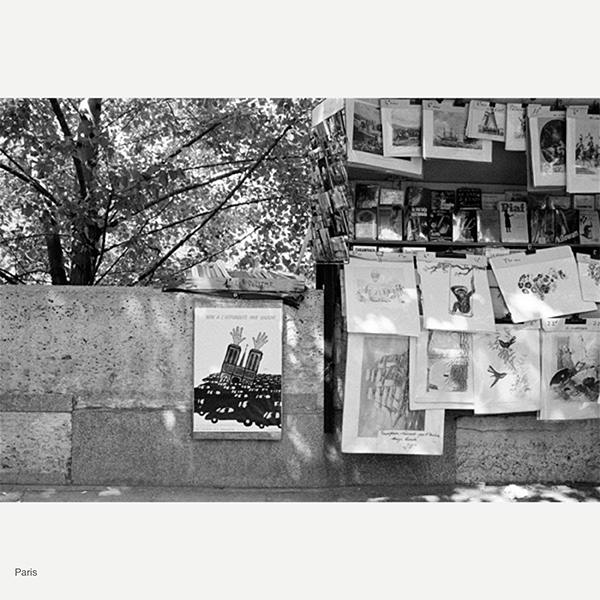

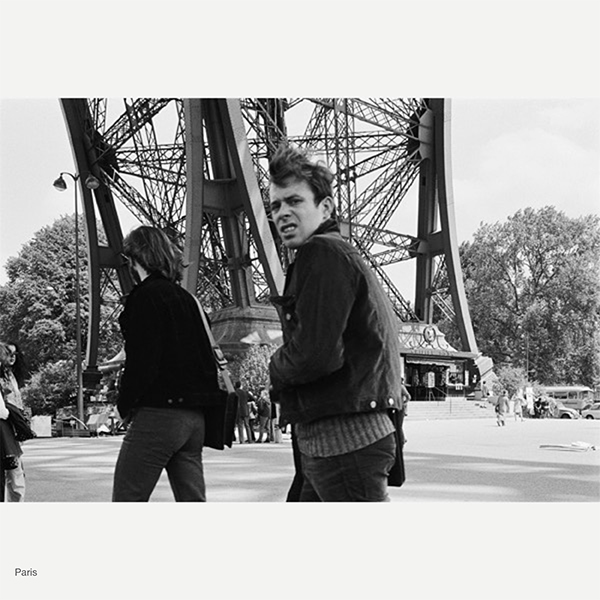

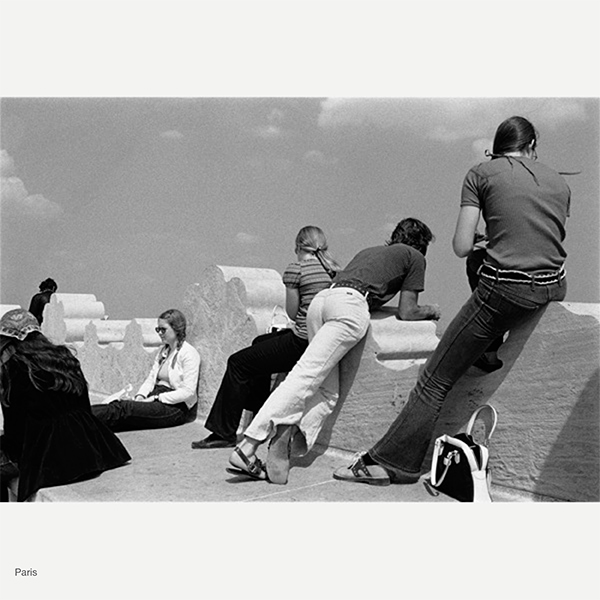

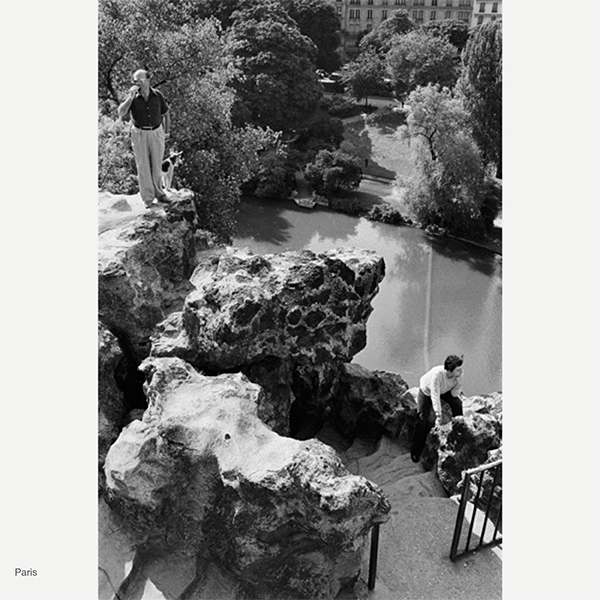

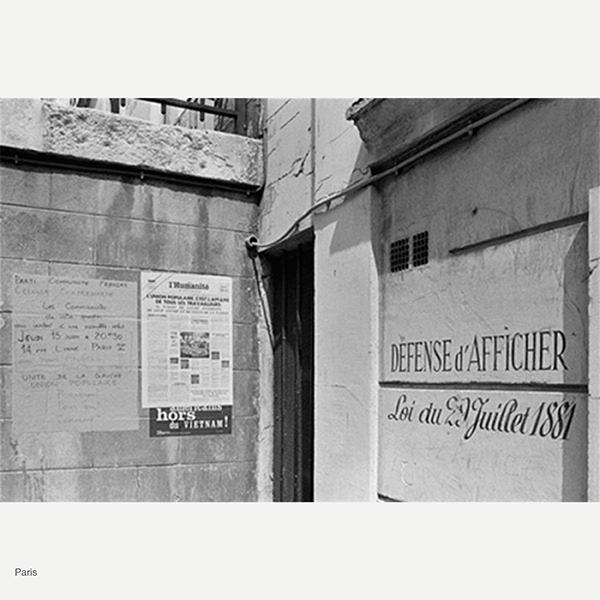

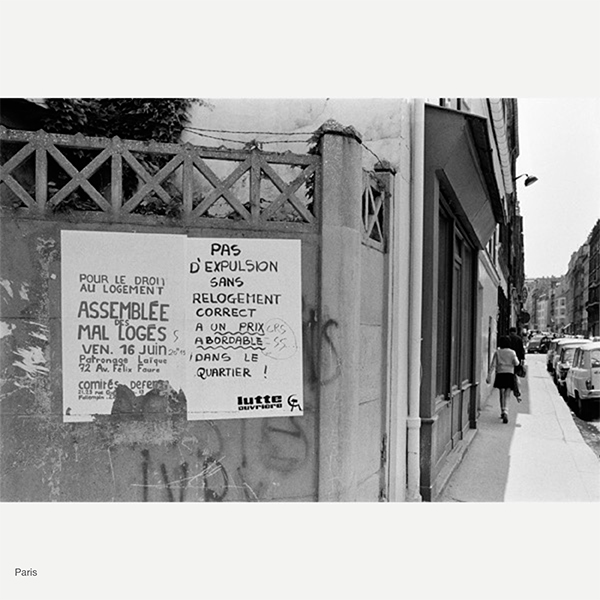

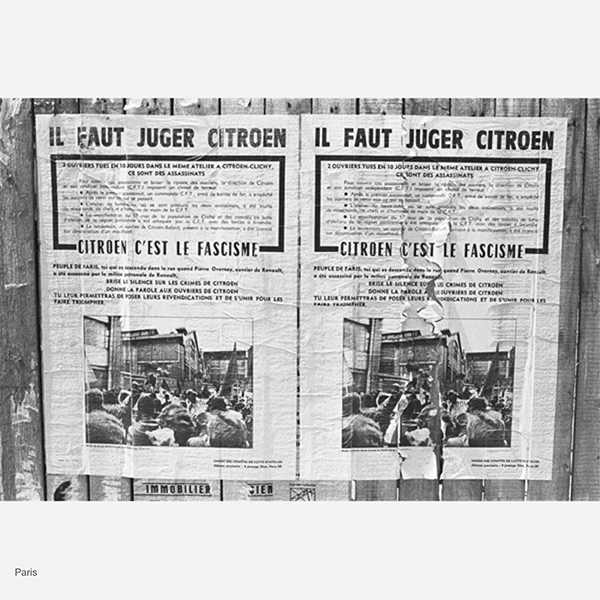

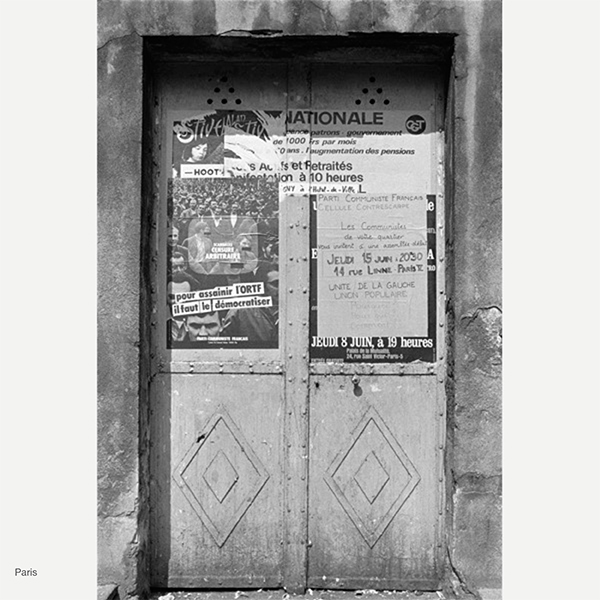

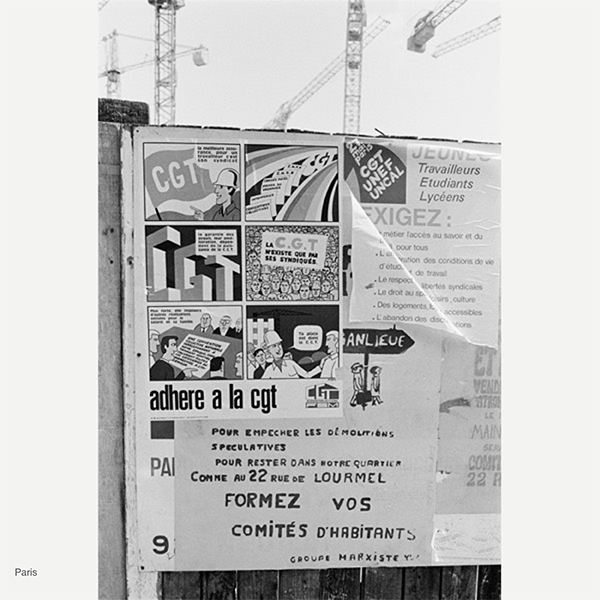

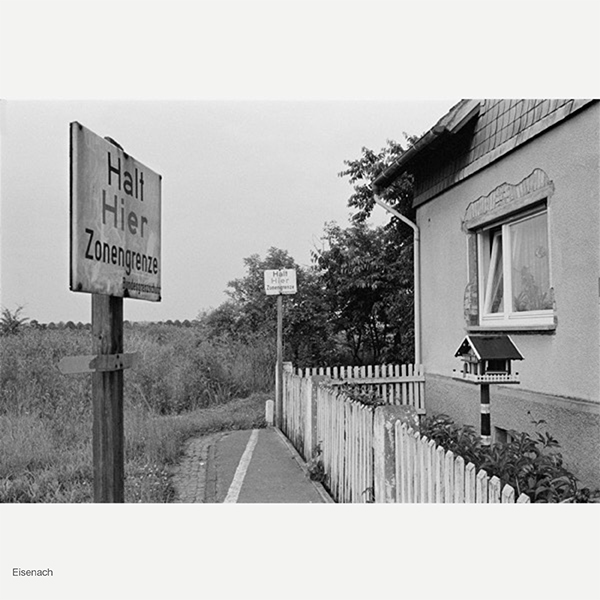

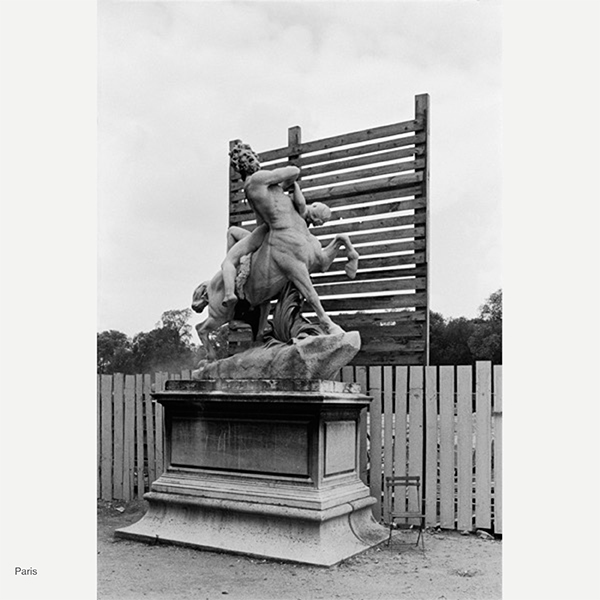

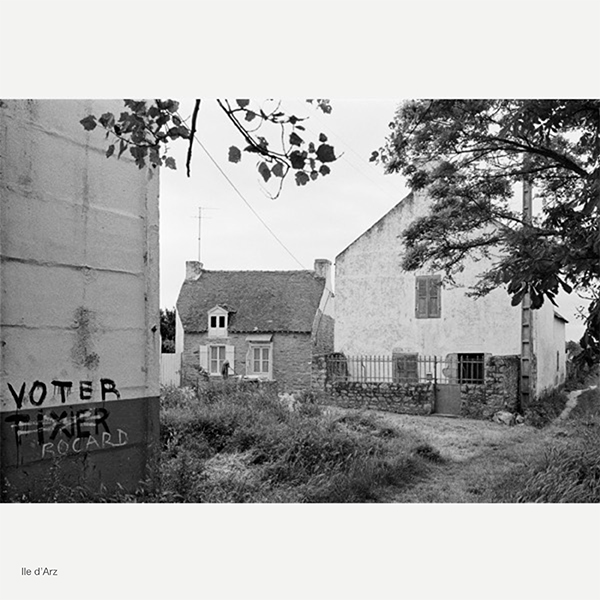

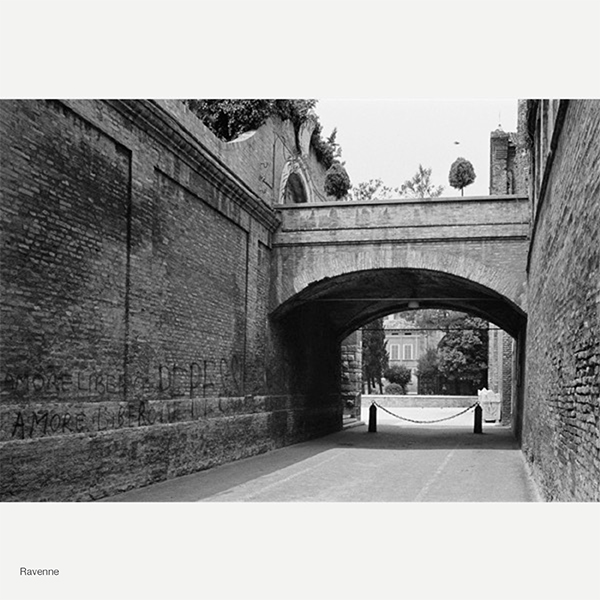

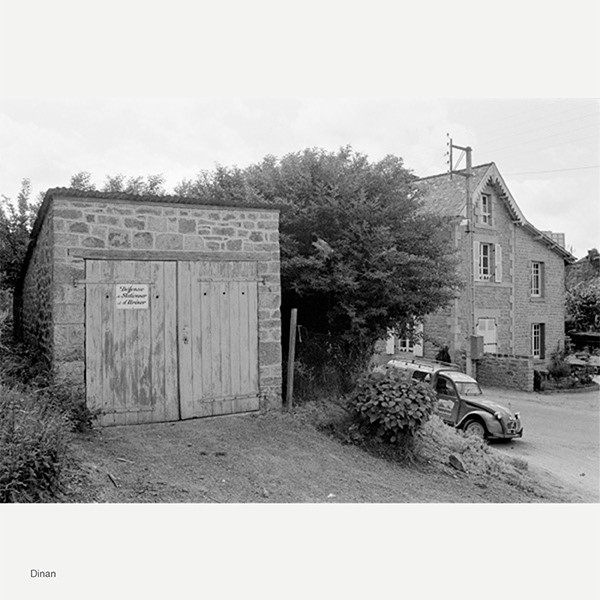

Fresh off the plane in Paris in 1972, I realized that Montreal was not alone in its confrontation with mid-century progress. From the first moment that I stepped out to explore the city, and always armed with the camera, I would see notices on construction hoardings condemning speculative housing, green awareness slogans in the Métro, and posters protesting against the construction of a highway on the Left Bank. Political posters were dramatically worded and graffiti scored the visual delights of the city.

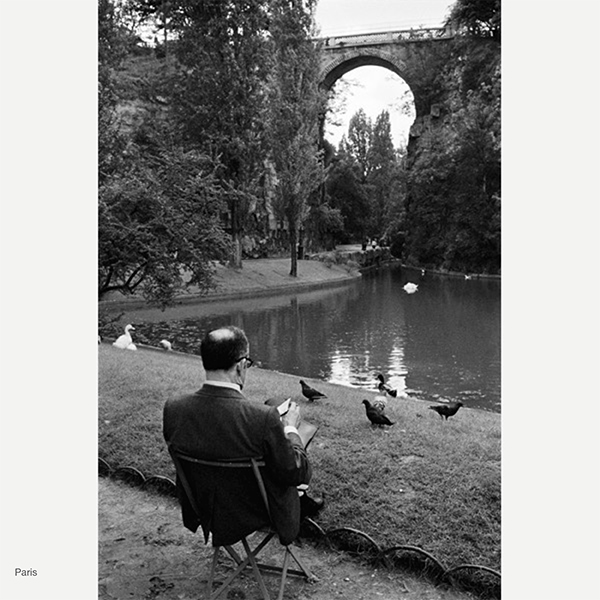

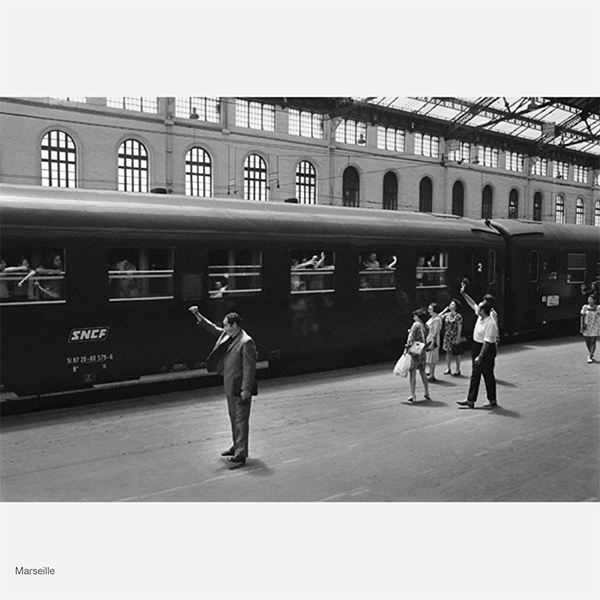

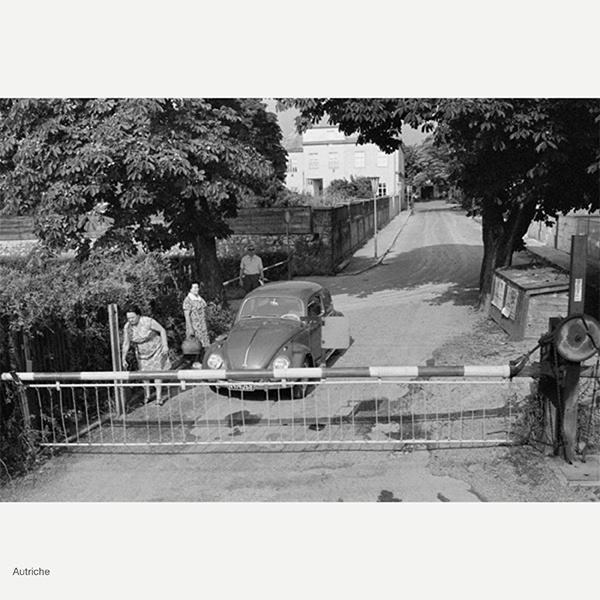

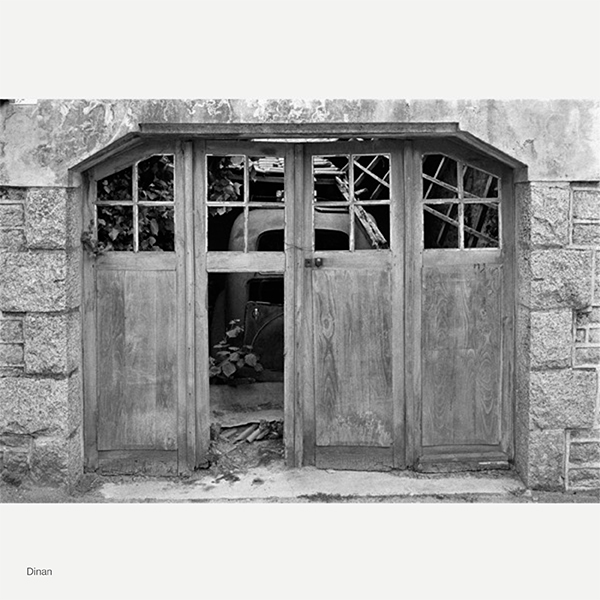

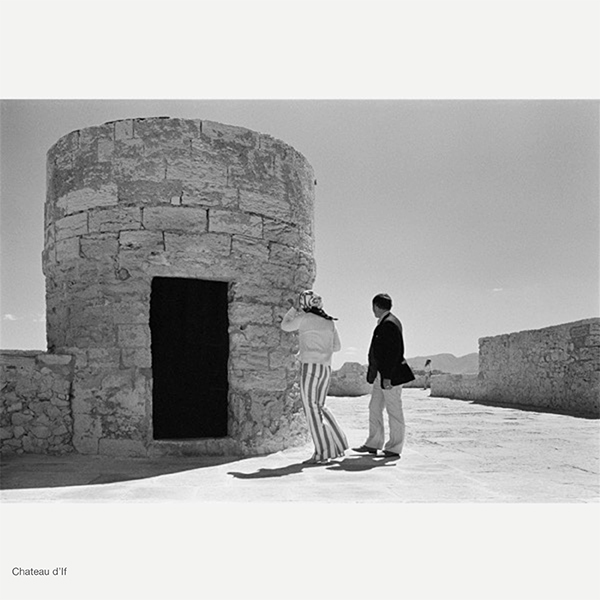

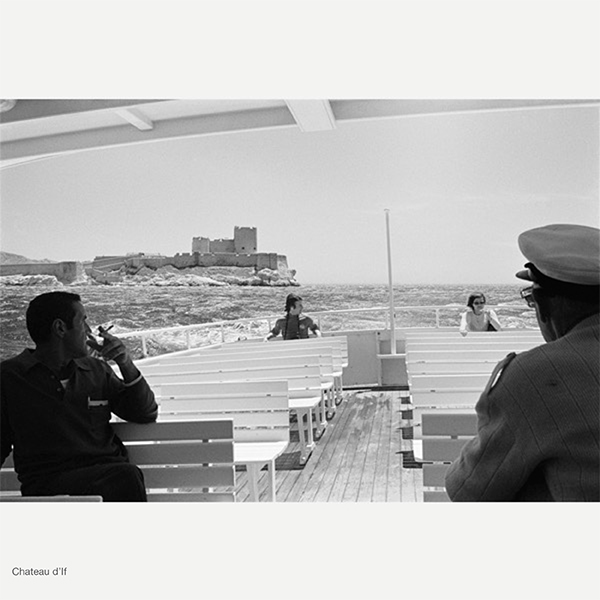

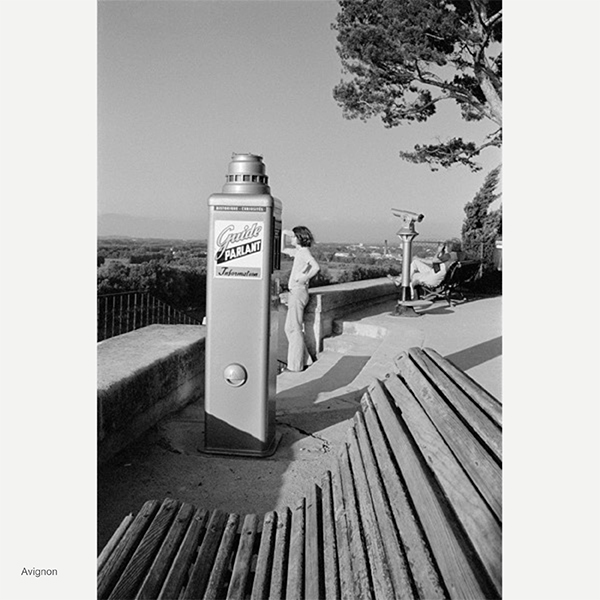

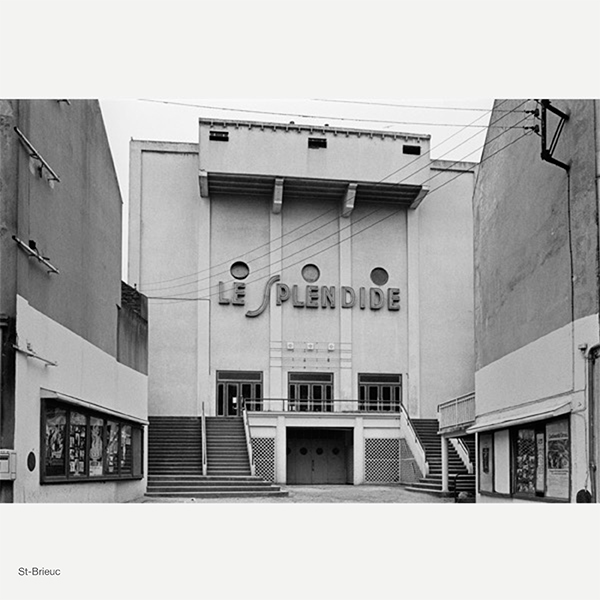

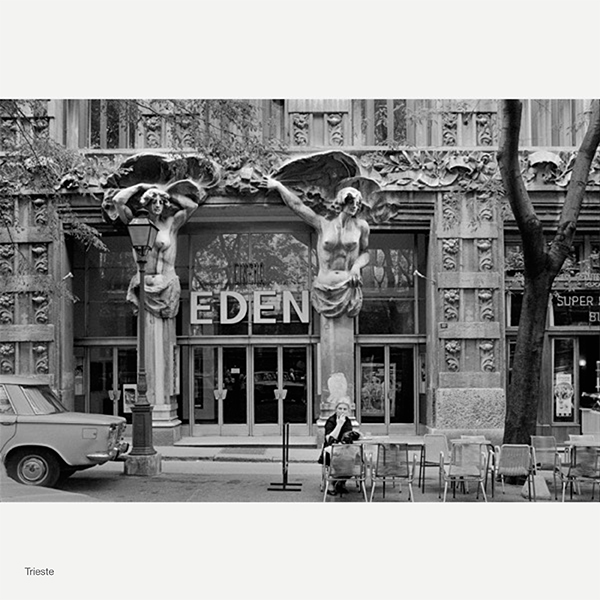

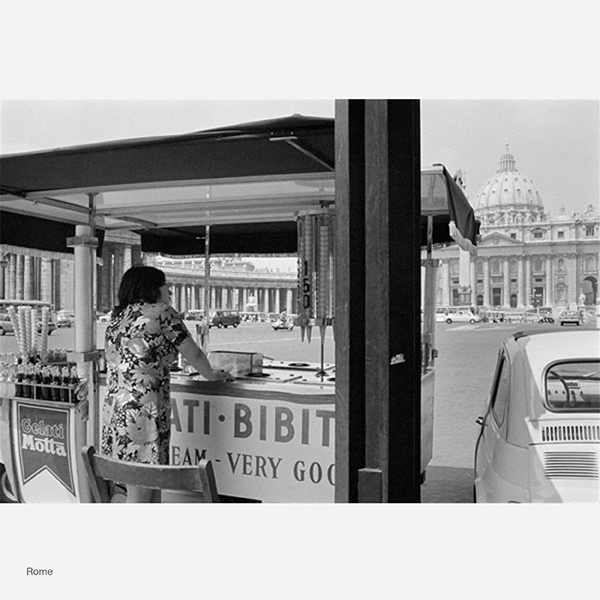

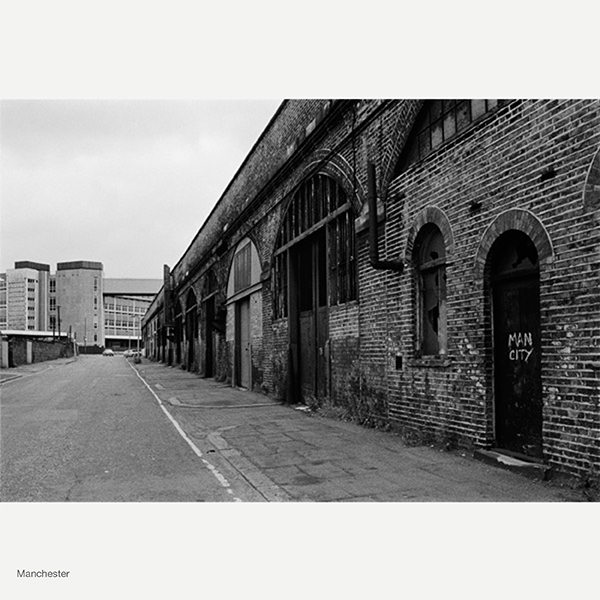

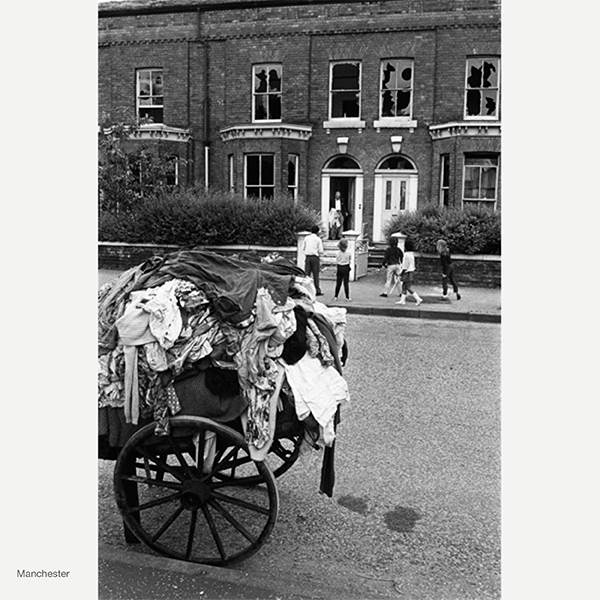

As the tour of Europe evolved, of course the landscapes, the agelessness, the juxtapositions of people, and always the trains were subjects of the camera, but in cities as different and distant as Trieste and Manchester, the themes of the environment and the demolition of housing drew me to interact. These became the nascent themes that have matured and crystallized over the span of my life, and, as we confront the irreversible crisis of climate change, the themes meld together. Today, municipalities are learning that the greenest building is the one already standing, that preserving the past helps form the future. Amidst the sooty diesels of destruction, the devastated industrial landscapes, today’s children are learning not to waste.

When we lose pieces of our past, we lose our history. Without history, we cannot knowledgeably form a future, we cannot properly educate our children, and we cannot enjoy a broad perspective of visual witness to that history. I dedicate this project to Lumi and Ida; to Jackson; to Violet and Jaden; to Joey; to Keili Mei, Autumn, and Suvi; to Juno; and to Eva and the western Jackson. May you learn what is genuine, help strengthen what is good, help undo what is bad, and embrace one another and our Earth.

Also read: A Photographer’s Holiday, by Zoë Tousignant.

Brian Merrett has been a Montreal-based photographer of heritage architecture for five decades. His work has appeared in many solo, joint, and group exhibitions and in numerous publications, and is included in private, corporate, and public collections. From the late 1960s to the 1990s, he photographed the rapidly changing urban landscape of Montreal, working with Save Montreal, the Westmount Action Committee, Friends of Windsor Station, and Heritage Montreal. His 1973 photographs of the historic Shaughnessy House convinced architect and philanthropist Phyllis Lambert to purchase and restore the building, incorporating it into the Canadian Centre for Architecture. With architectural historian François Rémillard, he co-authored four books to build public awareness of the diverse architectural styles, buildings, and landmarks of Montreal and Quebec City. Follow him on Instagram @brianmerrett.