By Charles Guilbert

The arts were turned upside down by the advent of the internet and social media, and photography perhaps more than any other art. The uninterrupted flow of images on the Web creates both anxiety and saturation. This chaos may be echoed in the disturbances that Carl Trahan explored in his exhibition The Nervous Age, in which he revisited nineteenth-century discourses that were both pessimistic and premonitory.1 Notably, he quoted the journalist Stefan Buszczynski, who wrote, in La Décadence de l’Europe (1867, artist’s translation), “One must be deaf not to hear the thunder that growls in the distance.” Engraved on graphite bars arranged on top of each other, these words find a new resonance in an enlightening spatial and temporal shift. Elsewhere, Trahan highlights the sense of spiritual decadence caused by progress by quoting a sentence of Goethe’s, which accompanies two pencil drawings inspired by spirit photographs: “Where there is much light, the shadow is deep” (artist’s translation). Through these two examples, we can catch a glimpse of the basis for Trahan’s work: translation (from one language to another and also from one form to another), disturbing strangeness, politics, and history. In fact, his work will soon be on view at the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec; he recently received the museum’s award for contemporary art.

One might wonder what this introduction has to do with the stunning triptychs that Trahan has been presenting daily for two years on his Facebook timeline, for he declares off the top, “I don’t consider this activity to be part of my art practice. These images are found on the Internet, and I don’t alter them, contrary to what I do for my artworks. You might see a sort of curatorship in their association. . . For me, it’s more an amusement, puzzles that I invent for myself.”

Not only is the ambiguous status of this activity problematic, but so is its distribution, as we can see the triptychs only if we are Facebook friends with “C Joseph Wilfrid T.” “I maintain this level of privacy,” Trahan says, “to avoid complaints. The rules on the types of images that you can post on Facebook are very strict. All it takes is for one person to complain and the images will be removed.” By replacing his real name with names that belong to him but are usually hidden, he reveals and conceals at the same time – a state that is not dissimilar to the content of his images. Through this shifted identity, he both opens and distances himself. “It’s a bit like a diary that I’m making. I often try to make it so that the triptych matches the ambience of the day. Sometimes, it’s very sombre …”

Added to this is a lack of clarity with regard to the identity of the creators of the images that Trahan appropriates. “When I know the source of the image, I give it,” he says. “But often it isn’t given on the Internet.” The idea of the author is thus blurred. The images used are of all genres – documentary, art, advertising, science, family, pornography, and more – and from all eras. Trahan’s modus operandi also resembles methods that don’t belong to the field of art. “A friend told me that there are similarities between what I do and ‘mood boards,’ the collages of objects, images, and texts used by teams of designers to define the guidelines for a project, for example.”

So, why talk in an art magazine about a non-artistic, private activity by someone who doesn’t reveal his sources? Because Trahan’s approach involves a very interesting “performative” relationship with the image.

In a certain way, what is offered through his multiple triptychs is an attitude, a gesture, almost a ritual. It supposes, first of all, an intensive and continuous search for images, and is accompanied by fabulous memory work. “I collect images that make an impression on me or that I ‘click’ with. Then I classify them in folders: ‘glasses,’ ‘chair,’ ‘curtain.’ My goal every day is to make a ‘sentence’ with three of these images, to make links between them. Often it takes patience to find the third one, whose ideal function is to take us somewhere else. I use Tumblr the most. People on that site present their own collections of images, found or original. What you see there is often random. I’m looking for organization. Sometimes I even take a number of images from a single collection to draw connections.”

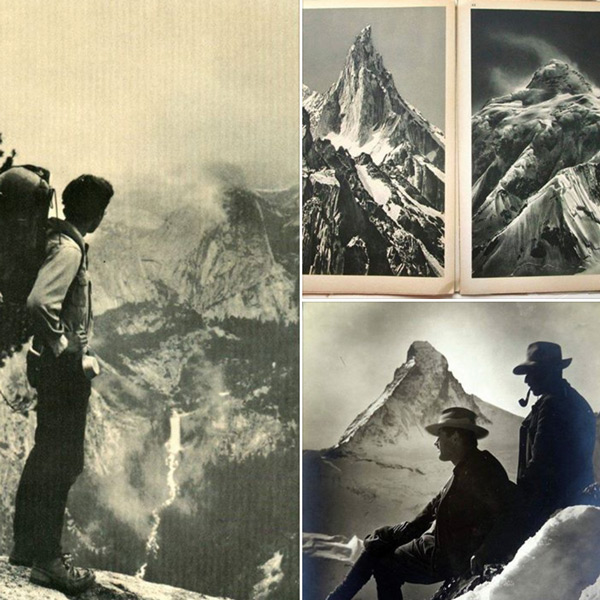

By creating new correspondences, Trahan brings images out of atomization. His meaning-laden aggregations force viewers to stop at the images and put aside the compulsiveness that is symptomatic of the Internet. Interestingly Trahan is contributing to another project, with an American woman living in Warsaw and an American man from San Francisco (smallpercentage.tumblr.com). Together, they have created a long series of related images. A red line is drawn; a logic is established resembling that of the catalogue. But since we have to scroll the images to see them, we are quickly plunged once again into frantic consumption of images. The finiteness of Trahan’s triptychs, on the other hand, invites us to be immersed in signs and contemplation.

For Trahan, this assembling is a way to give shape to time lost on the Internet: “In a way, I want to make procrastination more productive.” Thus, the uncontrolled voyeuristic impulse is subjected to a certain degree of control and a sense of usefulness is injected into idle wandering. “However, I don’t have the feeling that it is useful to my art practice,” Trahan insists. Because of its non-institutional, ambiguous nature, this play of triptychs seems almost absurd, in the sense that Albert Camus intends it: the search for meaning, the inconclusiveness of which is fully assumed, must be restarted each day.

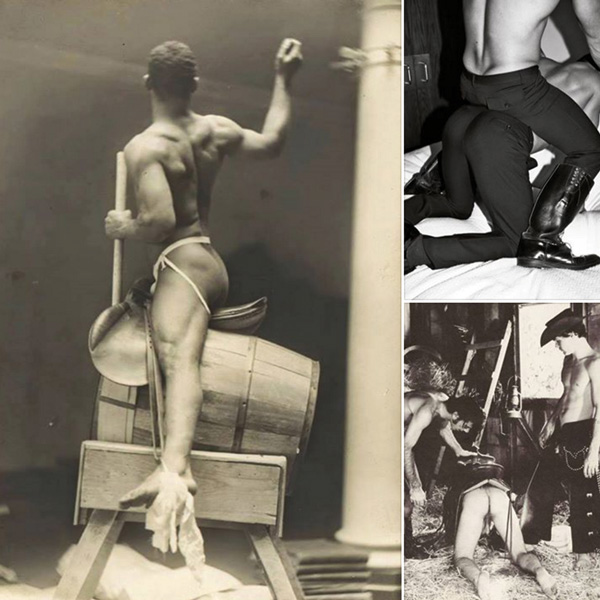

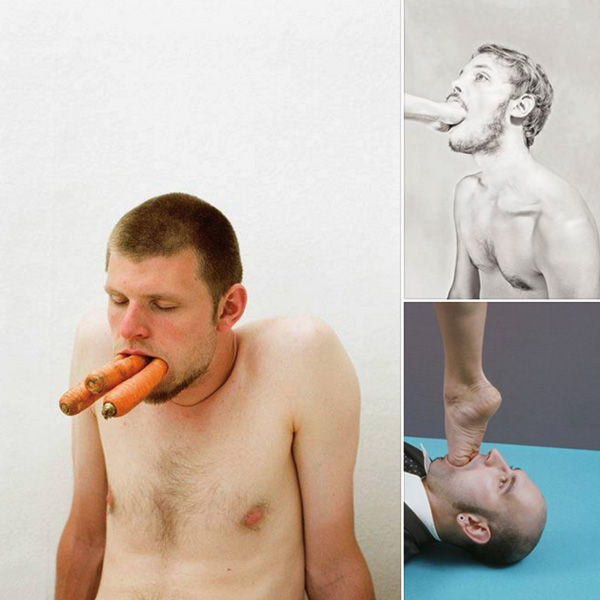

If the activity is, as a whole, “performative,” each triptych may also be considered a “performance,” in the sense of exploit, prowess, challenge met. “Entertain and surprise” – these are Trahan’s goals. He achieves this by choosing images that are surprisingly incongruous (a horde of nudists climbing a pine tree at night), poetic (a flower-delivery man facing a snowstorm), vulgar (a man urinating in the mouth of a plastic dinosaur), improbable (a nude youth standing and reading Nietzsche), strange (a kangaroo holding a plush rabbit in its arms), kitsch (a porcelain Elvis astride a real yellow cat), naughty (an erect penis emerging from behind a tree), disturbing (a bloody hand placed on a white shirt), ridiculous (a man with a blue parakeet perched on his head), unsettling (buttocks striped by lashes of a whip), or sublime (a sunbeam held in a fist).

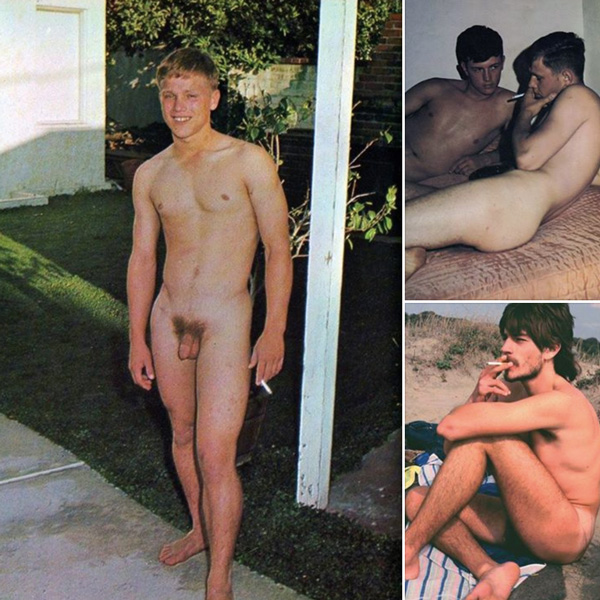

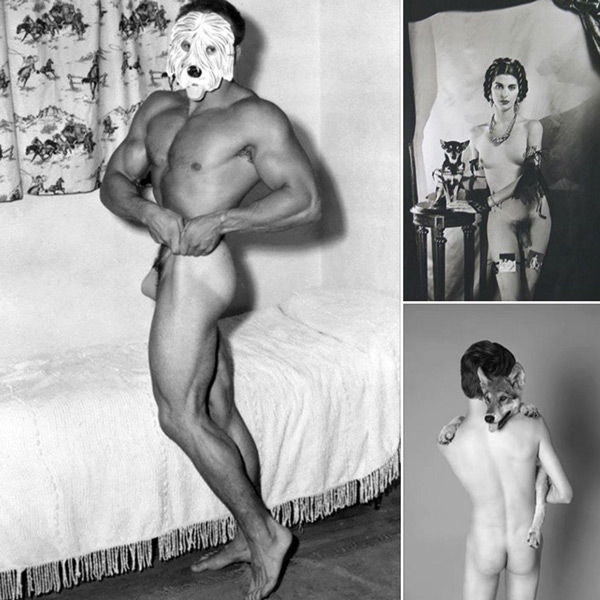

But what is most surprising is Trahan’s capacity to refresh our gaze by adopting various combinatory strategies. As we discover the relatedness of the images, we get a sense of extraordinary coincidence. How was he able to find three pictures of people wearing a wooden or cardboard box? Or images of bodies completely moulded with silver materials? We are often amazed at the large number of common traits among the pictures in the compositions; for example, the triptych in which each image presents both a black dog and a face enclosed in a hole; or the one featuring isolated arms all of which look metallic. Sometimes, it’s the tenuousness of the connection that is touching: the presence of tiny iridescent reflections in three very different images, or the similarity of the oblique line drawn by a body and a tree. Other times, the link is so anecdotal that we are surprised to see it highlighted: the cigarettes being smoked by these naked men or the white socks that these other people didn’t bother to take off before screwing.

In the task of categorization, a true inventiveness is at work. Here, the archivist doubles as a poet who is free to discover new types of divisions: a colour, a texture, a detail. Among the hundreds of triptychs Trahan has posted so far, recurrent themes are, of course, discernible: animals (dogs, deer, birds, horses), veils and curtains, watercourses, masks, antique sculptures, hands, reflections of all sorts. But when a motif is revisited, it is because its evocative power has not yet been exhausted.

The most common subject is no doubt the male body, partially or completely nude. We quickly understand that through these gatherings of images Trahan is pursuing an exploration of desire, as it was defined by Deleuze and Guattari: “If I should use the abstract term for desire I would say constructivism. To desire is to construct an assemblage. It is to construct an aggregate. The assemblage of the skirt, of a sun ray, of a street. . . . You never desire someone or something. You desire an aggregate. . . . Our question was, ‘What is the nature of relations between the elements in order for there to be desire?’”2

These relations, notably between body and territory, seem to have been forgotten in contemporary pornography, with its multiple close-ups of genitals. This is not the case in the erotic and pornographic images, many of them “vintage,” that we find in Trahan’s triptychs. “I like the filter of the past that allows us to address images in a different way. Before the 1990s, we paid particular attention to ambience, to décor. And many scenes sometimes had an oneiric, surrealistic character.”

What is also surprising is the way in which Trahan has us slide from an analytic – I would even say semiological – gaze to a desiring gaze. In flushing out recurrences, he shows what there is that is constructed in the images – the pornographic ones, among others. For example, in his triptych of nude men standing in stripped, uniformly blue spaces, we look first at the colour, surprised by this shared choice by art directors. After passing from one nuance to another, our eyes go from one body to another, then from one body to a blue, to another, and suddenly the strangeness of these scenes is reactualized. In his assemblage of assemblages, Trahan returns fluidity to a fixed assemblage and returns us to the source of desire, to the underlying feeling of immanence. Sometimes, it’s an imaginary snapshot that is appropriated – for example, the one of the cowboy; through the variations in the ride, the choreographic, playful, and even funny aspects of sexuality are revealed.

Can one achieve this tour de force without making art? The question may be asked, but should it be decided? The triptychs are far less conceptual than are the artworks that Trahan shows in galleries and museums. They are also less serious, less austere, less enigmatic. But despite their extravagance, frivolity, and fantastical side, in many respects they match the concerns in Trahan’s more “serious” productions. Words sprinkled here and there recall his strong interest in languages. And then there is his fascination with what is hidden, with the relations between art and design, with heterogeneity, with light, with history, and so on. We might even see, in the play of the triptychs, a political and critical side, certainly less direct than in the exhibitions The Nervous Age and Notte elettrica, for, through his persistence and his commitment to true surprise, Trahan is resisting both the generalized attention deficit into which our new “nervous age” seems to be slipping and the tyranny of algorithms that try to persuade us to let machines desire in our place. To keep us from losing our essence, an ethics of assemblage is welcome. Translated by Käthe Roth

2 Excerpted from L’Abécédaire de Gilles Deleuze (1988), directed by Michel Pamart (our translation, adapted from Charles J. Stivale – “A–F Summary of L’abécédaire de Gilles Deleuze,” accessed July 25, 2016, http://www.langlab.wayne.edu/cstivale/d-g/abc1.html).

Charles Guilbert writes prose, poetry, a journal, and criticism. He draws, sings, and makes videos. His works are presented in various countries, including France, Luxembourg, Mexico, and Japan. In Quebec, he has participated in the Biennale de Montréal (1998) and the Manif d’art (2005), among others. In the Fall 2016, works created with Nathalie Caron will be exhibited at the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec and at Centre VU.