[Spring-Summer 2018]

By James D. Campbell

This round-robin exhibition featured powerful and evocative images of the original site of the recently abandoned Royal Victoria Hospital. Eleven Montreal artists were invited by the RBC Art and Heritage Centre of the McGill University Health Centre to tour the original site. It had been vacant since the hospital moved to the new Glen site in 2015, and they were asked to choose locations to photograph. Accompanied by Dr. Jonathan Meakins, director of the Art and Heritage Centre (and former director of surgery at the Royal Victoria, the MUHC, and then Oxford University), and Alexandra Kirsh, the centre’s curator, the photographers extensively toured the abandoned complex for surrounds that moved or inspired them. There were two tours, both chaperoned by the curator: one to give them a sense of the panoply of views available; the second, to take the photographs. The result of these walking tours, on-site research, and maverick artistic vision is a captivating group of eleven images, yielding vastly different views of the empty hospital, by noted artists Raymonde April, Michel Campeau, Serge Clément, Luc Courchesne, Yan Giguère, Angela Grauerholz, Marie-Jeanne Musiol, Roberto Pellegrinuzzi, Yann Pocreau, Gabor Szilasi, and Chih-Chien Wang.

April’s Detail of a Window, Royal Victoria Hospital (2017) is a classically Aprilian image, if you will, in that, among the sheer multiplicity of places and purviews, she chose a window as both focus and threshold – a window that admits light – albeit in a state of some apparent disrepair, like organic things themselves. April always focuses on the “hard facts” of our existence – whether in the inner city, here in the hospital, or in the countryside – and yet she always evokes something numinous before and after those facts. This image suggests a sense of lateral and vertical compression akin to Hans Holbein’s Dead Christ (1521). The poiesis that we find in all her work, her openness to the world, is meaningfully reprised here.

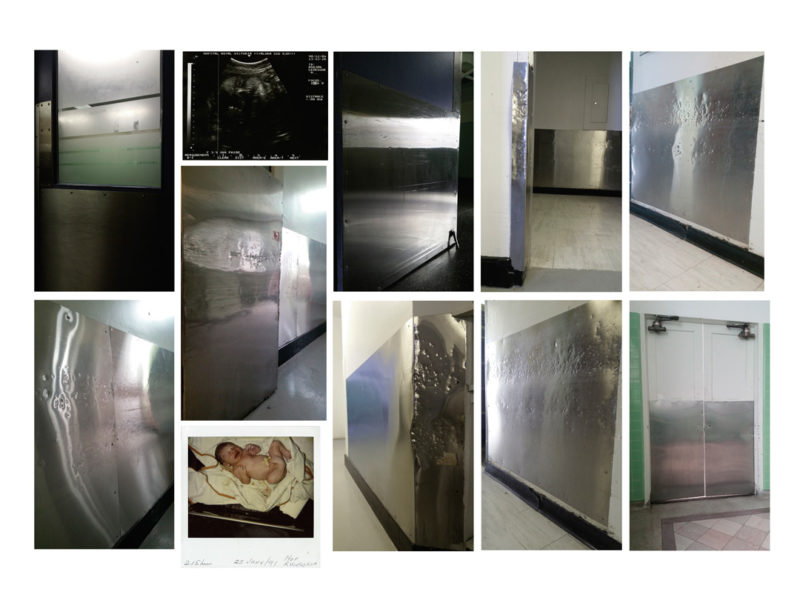

Campeau’s Baby Philomène Royal (1991–2017) (2017) is a collage built around the image of a baby born in 1991. The surrounding images feature stainless-steel surfaces, and there is another that is perhaps an anomaly scan, a detailed ultrasound image that depicts the baby’s body and observes the position of the placenta, umbilical cord, amniotic fluid, uterus, and cervix. The crying baby in the lower quadrant is sandwiched between the images of stainless-steel walls as though in the close embrace of a technology that presses in from all sides, the harsh metal contrasting with the newborn’s flesh like an alien armature designed to protect it.

In Royal Vic_002 – Montreal, Quebec (2017), Clément creates an evocative image of a darkened room, and it conjures a moment of crisis – perhaps suggesting a patient having gone sour during the night – and the shadowy profile of a nurse moving quickly across the room in response. Closer inspection reveals that what seems to be a bed with rumpled sheets may be a shelf with papers; the profile of the nurse, only a dusky stain. So, two revenants are manifested here: the absent patient and the hazy nurse in attendance, all gone quiet and dark.

Courchesne’s Recovery Room, Women’s Pavilion, Royal Victoria Hospital (2017) captures with eloquence and clarity, via a spherical camera, the atmospherics of a hospital interior – the recovery room in the women’s pavilion once the furniture was gone and the space stood abandoned. He felt that he, too, could “see the ghosts.” Like some of the other photographers in the show, he somehow captures temporality itself.

Royal Victoria Hospital, Montreal, February 3 (2017), by Giguère, is the only exterior view in the show. It is a stunning view from the main entrance, a view shared by so many visitors to the hospital over the years. The perspective is somewhat aslant, the sentry box seems in a state of disrepair, and the whole Gothic tableau reads as a startling indication of the hospital’s abandonment; its capacious, hungry façade receding, as if in time, consumed by the many decades of use and familiarity that precede the taking of this eloquent image.

The subject of Grauerholz’s Between Two Doors (2017) is the gap between two doors tied open between empty shelves. The fact that the doors are open and tied to one another’s handles suggests that open passage is paramount here, perhaps for the exodus of equipment, but it also evokes a sense of transience, a state of transition between the utility of the past and a still unknowable future. The classic Grauerholzian palette is, as usual, vastly seductive.

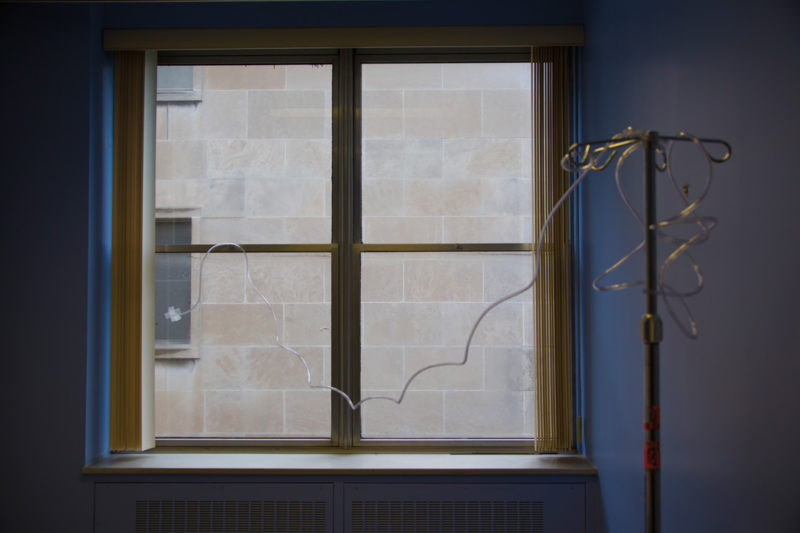

For Diane’s Escape (2017), Musiol sought out the liminal rather than the purely architectural, and she found it in an image named for someone whom she accompanied on her passage from this life. The space that she chose, which had been part of the breast clinic, seemed to segue with that experience in a room on the tenth floor of the S block. She found the IV pole in the basement and inserted it into the “staged” scene, then taped the tubing to the window herself as an expression of precious life force leaving the body at the moment of death. The window itself faces a blind wall with its own window, suggestive of passage into the afterlife.

Pellegrinuzzi, in Sans titre (2017), takes as his subject a room that has the mien of a futuristic artefact – an inside view of the United States Spacecraft Discovery One (or XD-1) from Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, perhaps. Its purpose is entirely enigmatic, although it was presumably an operating room of some sort: articulated lamps illuminate the otherwise darkened room; the station between the lamps is outfitted with sundry outlets, bars, and knobs; the wheeled storage bins is still replete with an array of objects. The image identifies medical technics without revealing their purpose, and this mystery animates the image and haunts the viewer.

Pocreau’s The Clock, Royal Victoria Hospital (2017) takes as its subject the hand-wound clock in the clock tower of the Women’s Pavilion, its face illuminated by a circle of lights and its mechanism removed. Since the hospital has been abandoned, it was important for Pocreau to identify the clock’s stoppage. (This clock is one of only three like it in existence — the others are at the Smithsonian Institute and the Library of Congress – and it was donated to the hospital by Walter M. Stewart in 1926.) Until its mechanism was removed in 2015, it was kept in a closed room on the building’s top floor. Security staff was instructed to wind it every three days. The symbolic value of the clock shorn of its use function seemed, for Pocreau, the perfect closing punctuation to the institution’s lifespan as a centre of the healing arts.

In Szilasi’s Operating Theatre (1924), 29 Mars (2017), the subject is the operating theatre in the Women’s Pavilion. The empty gurney speaks eloquently of the operations that were performed and observed there. (The seats for medical students and residents to observe surgeons – their professors – at work are in the upper register.) The image is classic Szilasi in that it gives a wealth of detail of a documentary nature while summoning up a powerful atmosphere of chilly winter. (Interestingly, this theatre was in constant use for almost a hundred years.) There is no ambiguity in reading this photograph – it is clearly a view inside a hospital. It enjoys great formal clarity, which is certainly why Szilasi chose it.

Wang’s Blue Wall with Lamp (2017) marked the return to where his child was born, but he resolutely chose not fetishize or sentimentalize the place in any way. His image features a lone lamp that is unplugged, just as the hospital itself is now unplugged. The palette is interesting in its institutional shade of pale to deep blue. In contrast to Szilasi’s image, we may not know that we are looking at a view taken inside a hospital, but the fact that the lamp is unplugged and some interesting and unused wall outlets adjacent to it suggest desuetude and abandonment. It also evinces the simple selfless stoicism so characteristic of this photographer’s work.

What is perhaps most revelatory, if not surprising, about all the works in this exhibition (given the sheer breadth of talent involved), is not just the fact that the photographers, given the freedom to harvest the spirit of the hospital, so successfully tackled their personal choices of its myriad spaces, but that their images stayed so identifiably true to and redolent of their respective aesthetic canons. This is certainly a tribute to the curator who chose these gifted photographers for the task at hand. Their perspectives add up to and meaningfully collate a sense of the whole that is radically more expansive and arresting – as an environmental installation – than are the individual images, and yet each of those images is almost iconic of the corpus of each photographer.

Entr’acte was titled after a 1924 French short Dadaist film in two parts directed by René Clair, which premiered as an entr’acte for the Ballets Suédois production Relâche at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées in Paris. There were eleven artists involved, just as there are here. The fact that the better part of the film was played as entr’acte between the two acts of the ballet makes sense in the context of the present exhibition as well, given that the present vacancy of the old Royal Vic places it, effectively, “between acts.”

However, having said that, for viewers looking for a surfeit of canonical beauty in photographic aesthetics or images, this is not the show for you. My father died in that hospital, and I still wake up at 3 a.m. to the sound of him screaming in his bed there. Not the happiest of memories. So a more recent film seems more relevant still: Arthur Hiller’s The Hospital (1971), in which Paddy Chayefsky, who wrote the screenplay, noted that the hospital emergency room was fraught with “the broken wrists, the chest pains, the scalp lacerations, the man whose fingers were crushed in a taxi door, the infant with a skin rash, the child swiped by a car, the old lady mugged in the subway, the derelict beaten by sailors, the teenage suicide, the paranoids, drunks, asthmatics, the rapes, the septic abortions, the overdosed addicts, the fractures, infarcts, hemorrhages, concussions, boils, abrasions, the colonic cancers, the cardiac arrests” and that the hospital as a whole housed “the whole wounded madhouse of our times.” Each of the photographers paid singular tribute to the hospital as a place of healing, in which all the above afflictions and more are addressed, but they also memorialized it as a place where treatments often failed – and patients died.

Kudos are due to curator Kirsh for assembling such talent and curating such powerful images. Kirsh says that a publication is planned in which all the images will be reproduced. After the exhibition ends, in March 2018, the photographs will be hung throughout the MUHC, where they will serve an even worthier purpose. As Meakins noted, “One of our missions is to create a healing environment. The art is primarily for the workers and the waiters – those who wait for this and for that, the people who need to be distracted from all the things going on around them.” If it is to be a useful distraction for the hospital workers, then it also a just, necessary, and, it is to be hoped, healing immersion in the aesthetics of images for both the workers and the healers.

James D. Campbell is a writer and curator who writes frequently on photography and painting from his base in Montreal.

Entr’acte, organized by the Art and Heritage Centre of the McGill University Health Centre, at Glen Site, Montreal, from November 2017 to March 2018.

[ Complete issue, in print and digital version, available here: Ciel variable 109 – REVISITER ]

[ Individual article in digital version available here: ENTR’ACTE

. A Collective Portrait of the Royal Victoria Hospital – James D. Campbell ]