[Summer 2019]

By Alexis Desgagnés

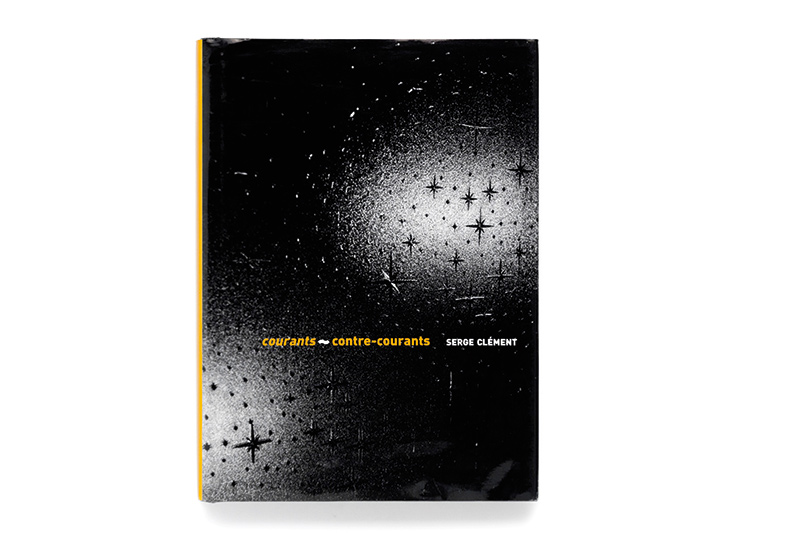

In 2014 in Quebec City, photographer Serge Clément and I presented the exhibition Constellations, composed of a corpus of photobooks drawn from Clément’s impressive collection. Our intention was to examine his privileged relationship with photobooks, and thus to encourage reflection on this type of work and contribute to its legitimization as art. At the time, art historian and curator Zoë Tousignant met with us to write an article on our project for Ciel variable.1

Over the course of time, Clément and Tousignant have developed a fruitful relationship. Tousignant organized the group exhibition Accumulations in 2015, featuring work by Clément, Michel Campeau, and Bertrand Carrière, and recently she curated his exhibition Archipel, a retrospective overview of his photographic mock-ups and photobooks produced since 1979, at Occurrence2 . I had the pleasure of getting together with them again, this time to talk about their project.3

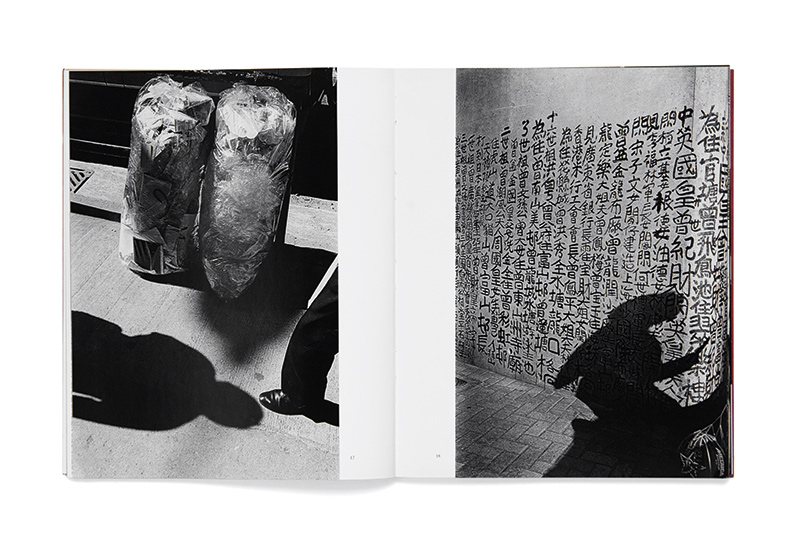

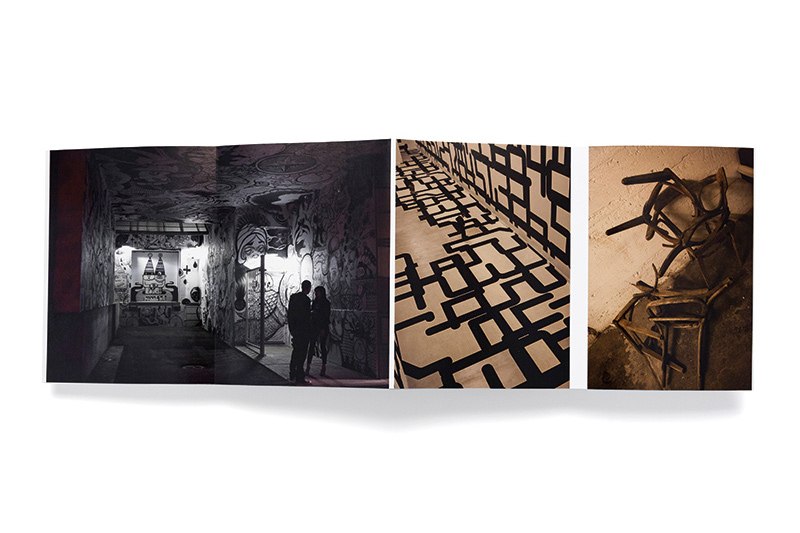

In the main gallery at Occurrence were a number of tables on which were placed various mock-ups and books that Clément has produced over his career. Although some of these objects were under glass or placed so that one could see them in their entirety from a distance, most were accessible so that they could be touched and looked through. Table after table, and each book one by one, the exhibition formed a kind of archipelago to be explored – a topographic overview of the photographic work that Clément has produced. Although no chronological path was explicitly proposed, it was possible to perceive a trajectory, a process, from the oldest mock-ups to the most recent publications.

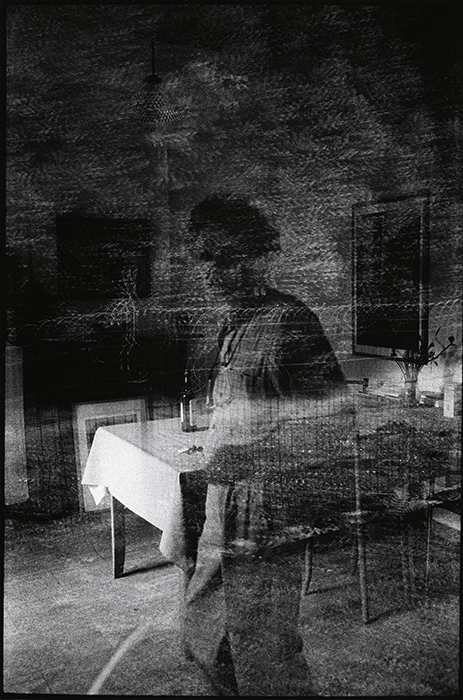

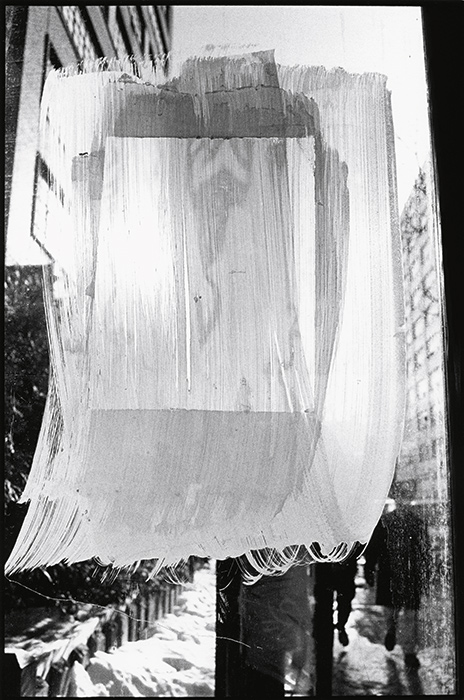

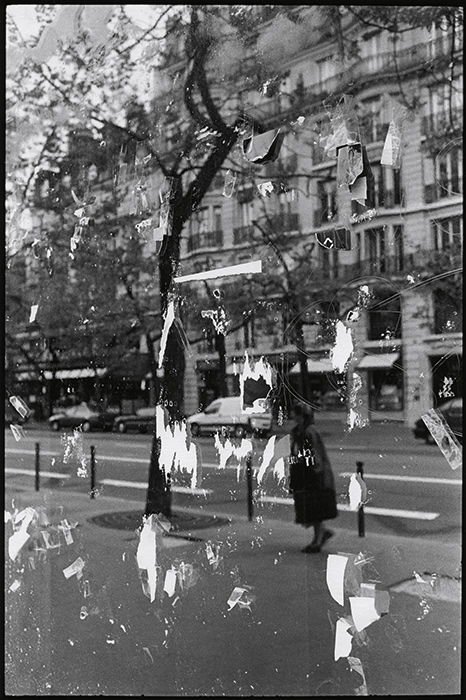

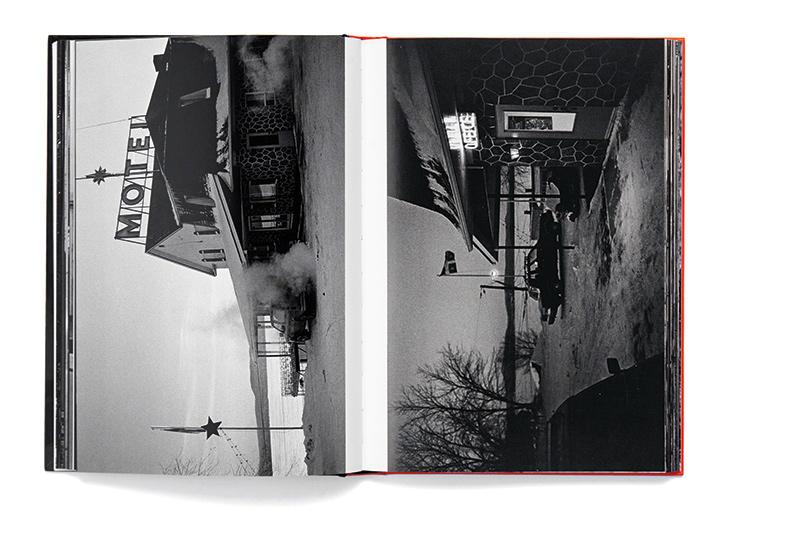

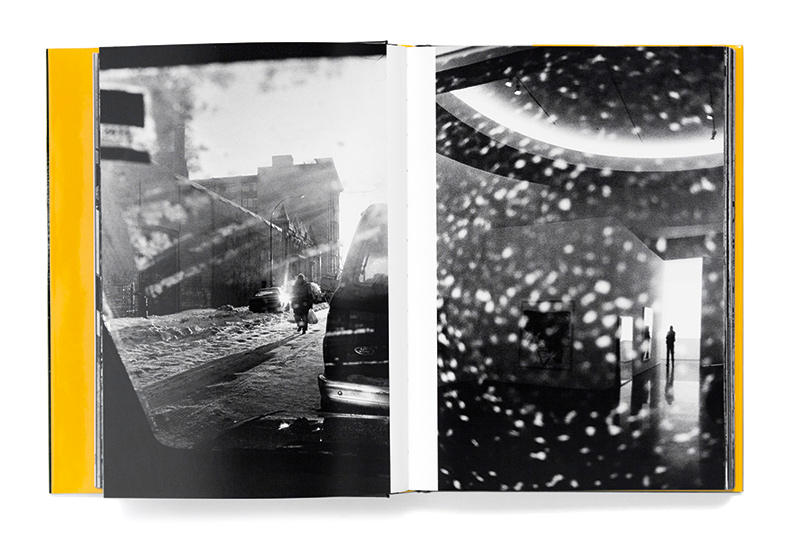

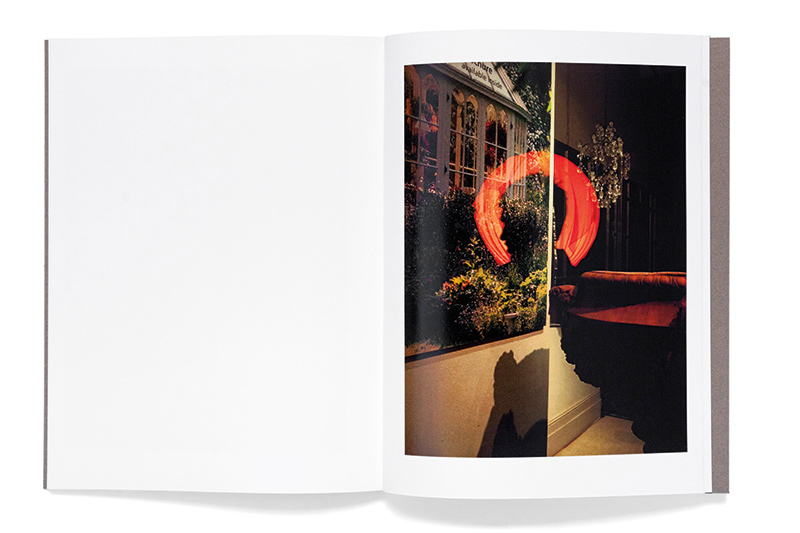

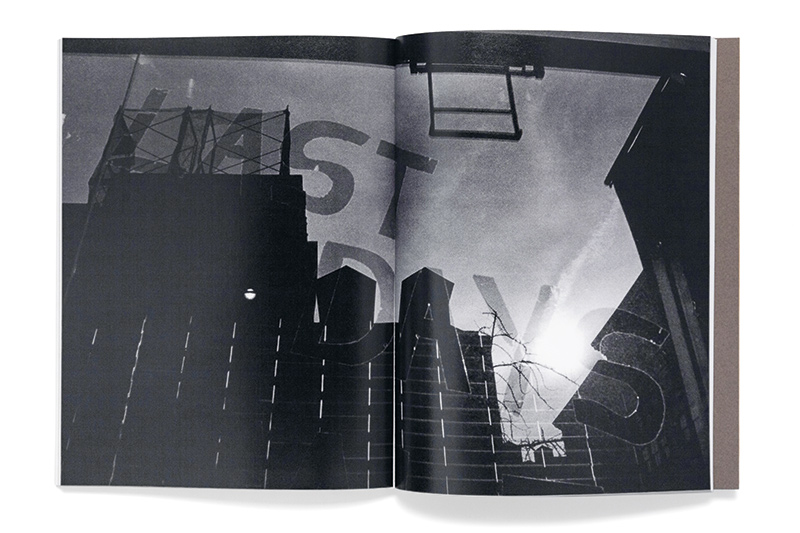

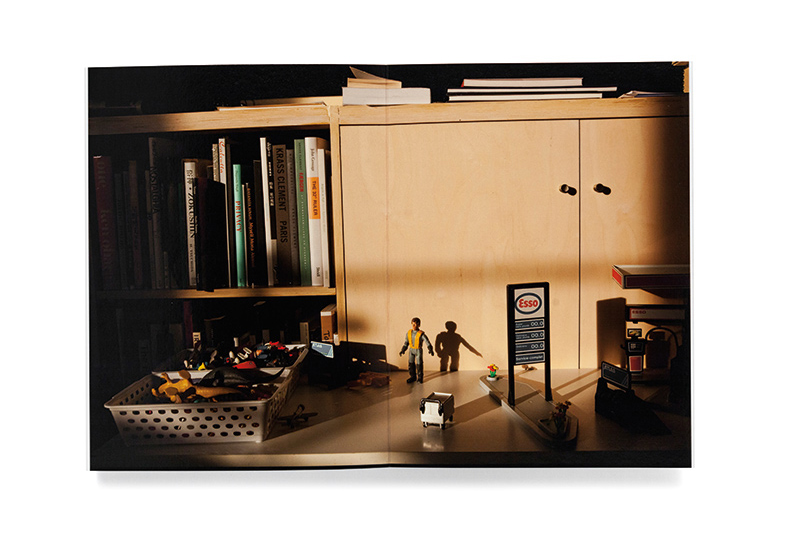

It is evident, from Affichage et automobile (1979) to Métamorphose (2016), that the city is Clément’s favourite theme, and it is woven through his body of work. As his images testify, he is a stealthy vagabond, a globetrotter on the look-out, who transcribes, often through the skilful plays on reflection for which he is known or by dynamic framings, the complex overlappings of the urban fabric and its visual culture. Although his photographic approach underwent no major aesthetic and conceptual ruptures, one can still see, in Vertige Vestige (1998), a slight change in his approach. Up to then, his practice had been based in the documentary genre, but now he seemed to turn more to a poeticized aesthetic. “We’re still in the real, but a real that is less attached to description,” Clément observes about his projects over the last two decades.

But again, aside from the content of Clément’s photo-graphic work, the exhibition highlights the importance that he has attached, over the last forty years, to variations of what one could call the book form. His intimate relationship with the book form was first embodied in a set of about a dozen mockups that he produced over almost twenty years (1979–97), all of which look similar and are intended for the same use.

Each mock-up consists of a single copy that articulates sequences of photographic prints mounted on cardboard or glued back to back and then folded accordion-style. Clément’s creation of this type of object, a sort of prototype through which a set of images is assembled and made coherent, is justified mainly by its intrinsic function. “The idea of using mockups to work on the sequence and meaning of my images,” he says, “was already there in my early photographic projects.” Thus, the mock-ups were both a tool used for experimentation and a form of manuscript intended to be shown in various contexts, and eventually published. “I made them with the idea that it was a form likely to interest publishers, with which one could reflect and possibly make a book.”

For Tousignant, it went without saying that these mock-ups would be in the exhibition. On the one hand, the desire to address Clément’s book production from a retrospective angle presumed that these “hybrid, experimental objects” would be displayed. On the other hand, the presentation of mock-ups corresponded to the art historian’s interest in the diversity of printed forms in the history of photography. In 2016, this attraction also led Tousignant to organize, at Artexte, an exhibition on Canadian photography magazines between 1970 and 1990.4 “Magazines are a sort of space in which aesthetic ideas and creativity are developed,” she notes. “My interest in them goes hand in hand with my interest in photobooks. Magazines and photobooks must be seen as equivalent art forms, as similar objects.” It was therefore natural for Tousignant to continue her research by exploring Clément’s mock-ups and other works.

It must be said that at the time when Clément was producing his first mock-ups, most photography in Quebec, beyond exhibitions, was disseminated through magazines. As he emphasizes, “What was being produced in the genre [in the 1970s] consisted of hybrid objects. There was no demand yet for the idea of the photobook. It was publications, magazines, that were diverted toward the idea of the book.” It is thus appropriate to situate Clément’s mock-ups, which he considers objects that are midway “between exhibition record and work on the sequence [of series],” in a context in which photography often circulated through hybrid media.

Even though Clément published his first books only in the 1990s (Cité fragile [1992] and Halloween [1997]), the choice that he and Tousignant made to include the mock-ups in Archipel is noteworthy. They mark a milestone in his creative process and it becomes obvious, upon consulting them, that their status is similar to that of Clément’s other books. Not only are visitors invited to handle the works thanks to the exhibition’s scenography, apparatuses, and furnishings, but they are encouraged by the very nature of the works presented – books! – and, in the second gallery, by a video showing overhead shots of hands leafing through them.

In the 1990s, Clément became aware of how compelling an experience photobooks provide when he took part in Les ateliers s’exposent, an event during which the Montreal public was invited to visit professional artists’ studios. Clément, who was presenting his mock-ups in his space, observed visitors’ reactions: “For me, it was a revelation to see how people reacted to those objects. I think it stimulated my desire to continue my work with books. I saw a potential with regard to reading images. With a book, you don’t have the same emotions as you do with photographs on the wall. With books, the relationship is physical; I think reading is more powerful than standing in front of framed images. It may be an illusion, but that’s the perception I had.” The attitudes of visitors to Archipel seem to bear this out. “I felt something similar at Occurrence,” Clément says, “where a number of people, instead of spending a few minutes in the gallery to make a quick round of the exhibition, took an hour, or even more, to look at the books, because they wanted to see everything, and even came back to see the exhibition. That’s what the experience of books is about.”

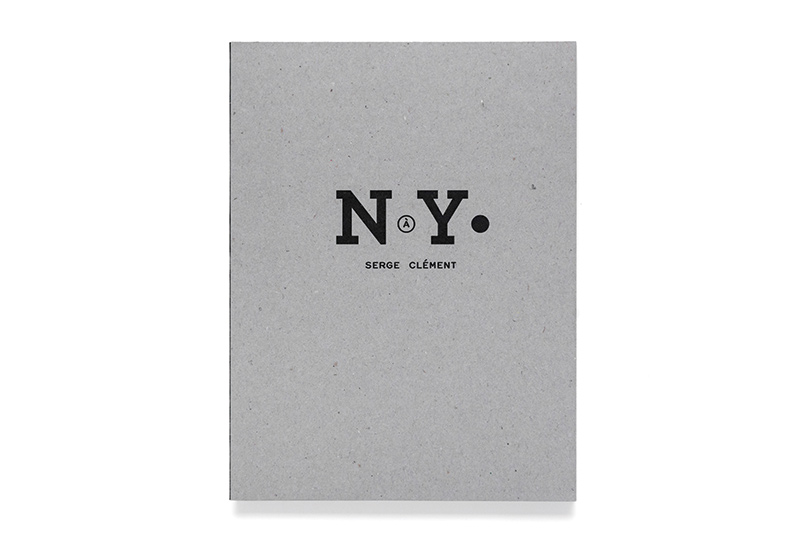

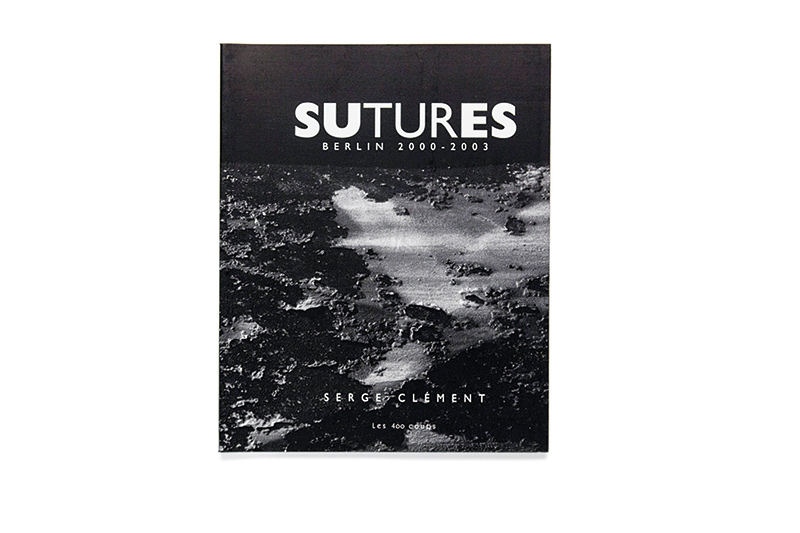

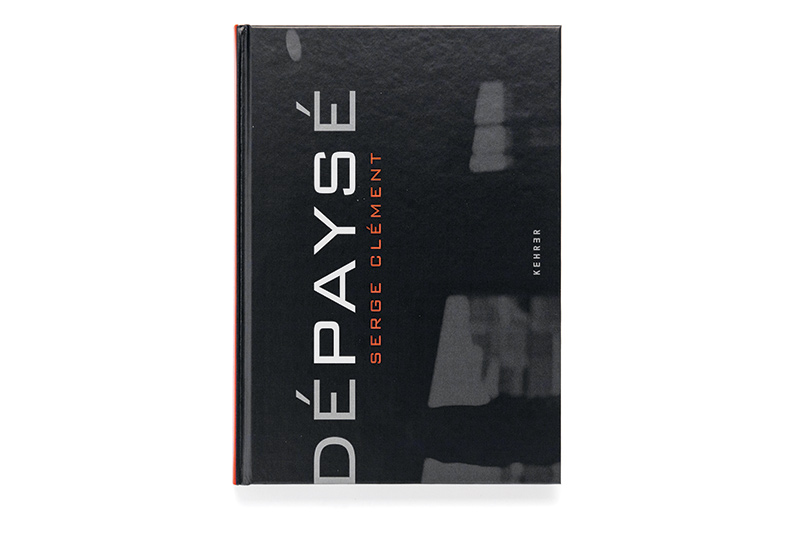

The fascination that Archipel undeniably arouses is ex-plained, no doubt, both by the coherence of Clément’s photographic universe and by the formal richness of the books he creates. It seems that each book project calls forth the form that is the best fit for his visual, conceptual, and poetic aims of the moment. Aside from the volumes mentioned above, there are large-format books, initially designed to be displayed outdoors, with their patina of time that now bears many traces of fingers, graffiti, and other stigmata left by previous readers. But above all is a newcomer in Clément’s bibliography: Archipel, the companion volume to the eponymous exhibition, published jointly by Occurrence and the French publisher Loco.5

Despite the book’s connection with the exhibition, I hesitate to speak of it as simply a catalogue. Of course, it differs from Clément’s preceding titles in that it has an informative dimension related to the scholarly work that Tousignant has produced for it. In addition to her introduction, she has carefully assembled a detailed bibliography covering twenty-seven of Clément’s mock-ups and books. Archipel also contains a fuller description of six volumes chosen by Clément from among those he has published since 2000.

With regard to her contribution to this publishing project, Tousignant says, “I didn’t want to interpret Serge’s works; rather, I wanted to describe them as objects that exist in time. I was certainly inspired by books like those by Martin Parr and Gerry Badger,6 who offer concrete descriptions of photobooks. Out of respect for the practices of librarians and archivists, my didactic essays respond to the fundamental desire of art history to value the art object by describing it in detail. Simply describing this object is, for me, a way to take it seriously as an artwork.”

Beyond the texts, the heart of the book Archipel is Clément’s selection of a hundred photographs, most of them taken from his books – a selection that, in Tousignant’s words, proceeds from a desire for “active reappropriation of his past production.”7 This new look that he casts on his images helps to update how they are interpreted and appreciated, which is why Archipel cannot be considered an exhibition catalogue. Rather, it is the latest in a long line of artist books. Let’s hope that the list will continue to grow in years to come.

Translated by Käthe Roth

2 The exhibition Carrière, Campeau, Clément: Accumulations was presented at Galerie Simon Blais (Montreal) from September 4 to October 10, 2015. The exhibition Archipel was presented at Occurrence (Montreal) from November 16 to December 21, 2018.

3 Unless otherwise indicated, all quotations in this article are taken from an interview that I conducted with Clément and Tousignant on Friday, January 18, 2019, in Montreal.

4 Magazines photographiques canadiens 1979-1990: reconsidération d’une histoire de la photographie imprimée, exhibition organized by Zoë Tousignant and presented at Artexte (Montreal) from September 8 to November 5, 2016. The essay that Tousignant wrote for the occasion is reproduced in Ciel variable 105 (Winter 2017): 44–51.

5 Serge Clément, Archipel, with text by Zoë Tousignant (Montreal and Paris: Occurrence and Éditions Loco, 2018).

6 Martin Parr and Gerry Badger, The Photobook: A History (3 vols.) (London and Paris: Phaidon, 2004, 2006, 2014). About these works, especially the third volume, see Alexis Desgagnés, “The Photobook: A History Volume III,” Ciel variable, 100 (Spring–Summer 2015): 93–94.

7 Zoë Tousignant, “Revisiter,” in Clément, Archipel, 5 (our translation).

Artist and author Alexis Desgagnés lives in Montréal. He teaches art history at the college level and is a union activist.

Serge Clément was born in Valleyfield, Quebec, in 1950. He has been a photographer since 1975 and devoted exclusively to art photography since 1993. His approach ranges from documentary to installation and includes social commentary, poetic narrative, and photographic essays. His works have been exhibited in Europe, Canada, Syria, China, and Japan and are in major institutional and private collections in Canada, France, Belgium, and Hong Kong. He is represented by Galerie Simon Blais in Montreal and Galerie Le Réverbère in Lyon. sergeclement.com

[ Complete issue, in print and digital version, available here: Ciel variable 112 – COLLECTIONS REVISITED ]

[ Individual article in digital version available here: Serge Clément, Archipel — Alexis Desgagnés, Geography of an Archipelago ]