[Fall 2019]

By Charles Guilbert

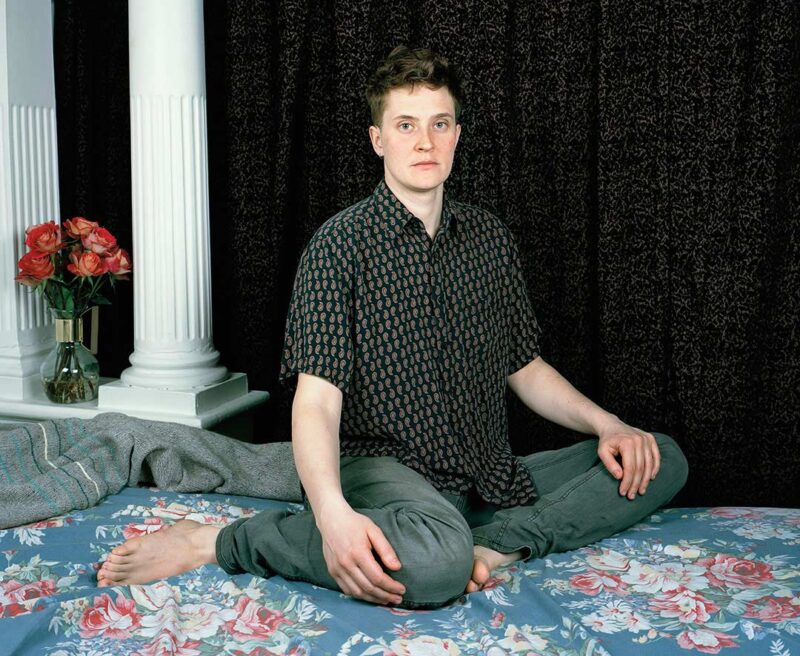

What strikes the eye in JJ Levine’s work is a unique way of challenging gender norms. But when we look more closely, we discover that Levine wants to erase many borders – in both photography practice and in addressing subjects such as family, time, and space.

Levine’s work is composed mainly of three series: Switch, Alone Time, and Queer Portraits. Although the corpus of the first series is complete, the other two are in continual development. Each image in Alone Time shows a couple that is, in fact, composed of a single person embodying male and female roles. Queer Portraits, as its title indicates, presents queer and trans people; the images generally contain a single person, but there are also duos and trios, and some include children.

Recently, thirteen photographs and a video from the Queer Portraits series were brought together for an exhibition titled Intimates,1 a sequel to Family, presented in 2016.2 Some images feature the artist and Harry – both trans people – and their child, Joah. In both exhibitions, Levine deconstructs fixed ideas on identity and social connections. I met with him to talk about the aesthetic and political stances underlying his art.3.

Charles Guilbert: In your works, you propose a totally unrestrictive definition of family.

JJ Levine: During my exhibition at La Centrale, someone said to me, “I understand why there are images of the two of you and your child and of your friends and their children, but not why there are also images of people without children.” I answered that that was precisely the goal of the exhibition: to broaden the idea of family to include friends, relations, everyone who feels committed to someone else. But even before I had a child, and before my friends did, I used the word “family” to talk about the people I portray in my work.

CG: So, for you, there shouldn’t be a hierarchy between biological and affinity families.

JJL: Exactly: I want these borders to be blurred. My friends are intensely involved in my child’s life, as are my many siblings, some of whom are queer too. I feel really lucky in that sense. And I see this type of solidarity in other queer families. In the short film Friends and Children Dancing, Shot on my Mother’s Camera, which I made in 2018, two women, Heather and Selena, dance with two children, Aylin and Joah. Neither woman is the mother of either of the children, and yet they both play a central role in their lives. Selena, who is one of my best friends and Aylin’s aunt, often takes care of them. Heather has chosen to share an apartment with Aylin and his mother in order to take part in the child’s upbringing. There is no word to name this parental relationship. And yet, it is very significant. It seems essential to talk about these connections, which, in a queer world, may be even more important than biological ties.

CG: In a sense, friendship is central to the queer ethic.

JJL: Partner and children: that’s what normally forms your world as an adult. Yet, friends are often there before a partner comes along. For me, being queer involves placing value in friendships and maintaining multiple relationships all one’s life. Energy is devoted to the resolution of problems that may arise so that these relationships will endure.

CG: One could even say that your approach to photography is inseparable from friendship.

JJL: I have close ties with all the people in my images. That’s what makes it possible to spend lots of time with them to create a portrait. It takes me between four and eight hours to produce ten or so negatives. The slowness of the process is linked to the care that we take of each other. The care that we put into the details that are found in the images testifies to the value of our relationship. There’s a direct link between the attention that I pay to my subjects and the attention that I pay to making images.

CG: This rapport with the close friends you photograph is also essential to allowing intimate space to be transformed into a sort of intermediate space that the viewer can enter.

JJL: Yes, I almost always photograph people in their own environment, but the space that I frame is completely reconstructed. I start from what belongs to them – furniture, clothes, accessories, and objects – to create a setting. Many people say that my work is documentary, but I resist this label. Everything is transformed so much! Yes, these are real people, real identities, real friendships, but the photographs themselves are not documentary. It’s not a moment I capture, it’s a moment I create.

CG: Indeed, one senses something intentional in the composition of the images.

JJL: Intentionality is very important to me. It’s the contrary of photographing someone by surprise, an attitude often seen in documentary images. I want the subjects to know that they’re being photographed, and they can prepare for days if they want. Everything is highly planned. If someone is nude in an image, it’s because they decided to be. They thought about what this involves and wanted the viewer to have this specific experience. The photograph isn’t a window into the person’s entire life. It doesn’t require the subject to make an offering of their identity. The frame gives only the information that I or my subject wants to give. The details one sees are the keys to the subject’s identity. They give the viewer permission to enter the image.

CG: This “modesty,” if I can put it that way, has something political to it.

JJL: It contrasts the way in which queer and trans bodies have traditionally been presented. In the history of photography, especially in medical and legal photography, or in the “freak show” approach, there is an undeniable violence, something very intrusive.

CG: There is something in the solemnity with which your subjects pose that refers to the tradition of the portrait.

JJL: I photograph queer bodies and identities in the same way that culturally sanctioned people of a particular class and identity were once photographed. The portraits made of them in the studio were an archive for posterity. The nuclear family was in the forefront in these images. Queer bodies were probably never photographed in this way in those times. They didn’t have access to the gaze that celebrates, elevates, and commemorates. By using this traditional approach, I create a sort of temporal ambiguity that I like.

CG: This play on temporal borders truly seems at the core of your aesthetic.

JJL: I avoid including elements in my images that make it possible to situate them in a specific time. For example, there is never a reference to today’s technology in my images. On the other hand, there are many elements that refer to bygone times – vintage furniture and objects, for example. At the time when these objects were manufactured, forty, fifty, or sixty years ago, photographs such as these, featuring self-assured queer and trans people, couldn’t have been made. I like pointing out this impossibility.

CG: Even on the technical level, you combine present and past.

JJL: I’m very attached to analogue media: I always use a film camera to take pictures. To create Alone Time, I did use a computer, as these were photomontages; I patiently brought together a number of negatives with Photoshop to make a single image. On the other hand, I continue to print my Queer Portraits in the darkroom, even the 40 × 50 prints, which pretty much no one does anymore. Printing one image takes me four to six hours. It also speaks of the presence of love in the work.

CG: Yet, your work is solidly grounded in today’s reality, particularly in how you present queer families.

JJL: Of course, it’s unusual to see an image of a pregnant man. But it’s not new for queer and trans people to have children. For me, it’s normal to make these images as it’s the life that I live. I feel that it’s important to circulate images of this daily life in the world, to show that these realities exist and that they aren’t one-dimensional.

CG: Does your work express a desire to normalize queer and trans identities or, on the contrary, a spirit of resistance?

JJL: I feel much closer to an anti-assimilationist, antiestablishment, and anti-capitalist approach, because I think they’re all linked. And I see that it’s possible to have a child without sacrificing one’s opposition to normative life choices. I resist dominant identity and I’m very critical of the government. Even today, the Quebec public healthcare plan doesn’t reimburse certain surgeries for trans people unless they agree to be sterilized, which is revolting. Being trans, having a body that matches how you feel, should not be connected to the right to have children. In this sense, transphobic bureaucracy can’t conceive of anything but binarity. Of course, there have been advances, but there’s still much to do.

Translated by Käthe Roth.

2 Family was presented at La Centrale in Montreal 11 November–9 December 2016.

3 This interview took place on 6 June 2019.

Charles Guilbert is an artist (video, installation, drawing, song, writing), art critic, and literature professor. Over the last five years, he has co-curated ten exhibitions with Marlène Boudreault, including Nos corps (works by JJ Levine, Rachel Echenberg, and Sylvie Cotton) last April.

JJ Levine is a Montreal-based artist. He holds an MFA in photography from Concordia University. Levine has been honoured with several awards and received grants from the Conseil des arts et des lettres du Québec and the Canada Council for the Arts. His work has been exhibited across Canada, the United States, and Europe. He has been a guest lecturer at universities and has had articles published in scholarly journals. He is represented by the gallery La Castiglione in Montreal.

www.jjlevine.com

[ Complete issue, in print and digital version, available here: Ciel variable 113 – TRANS-IDENTITIES ]

[ Individual article in digital version available here: JJ Levine, Family — Charles Guilbert, Beyond Borders ]