[Winter 2021]

Par Edward Pérez-González

The Single and the Multiple. Briefly, multiplicity can be defined as a condition that amplifies things and phenomena; a state of abundance, of potentialities, that enables us to perceive and comprehend the world through different and heterogeneous dimensions – from another dimension. This mode of the single and the multiple is precisely is found in the exhibition Les années musicales : 1920–2020, presented by VOX, centre de l’image contemporaine.1

“The multiple must be made,” say Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari,2 not by adding supplementary dimensions but by subtracting the unique. When this operation is conducted, rhizomatic systems appear, constantly folding, refolding, and unfolding. We sense their presence when we wander among the worlds contained in this exhibition, which produces a sort of disorientation among spectators, a struggle between the desire to absorb everything at once and the desire to let ourselves be led, let ourselves flow, according to the rhythm or silence around us.

Exhibition curator Marie J. Jean worked with the objective of providing a sensory experience through works that create tension between images and music, two dimensions that are more commonly subordinated one to the other.3 The exhibition is composed almost totally of films and videos, silent and with sound. It organically – not sequentially or chronologically – traverses a hundred years of the evolution of audiovisual art through a judicious selection of works that highlight a certain idea of art history: not the history of a succession of art styles, but the grouping and articulation of concepts, discourses, and theoretical intentions around artworks. Among these are surpassing the idea of beauty, abandonment of the notion of art’s functionality, and putting aside the meaning and autonomy of art.

Les années musicales : 1920–2020 does not seek to arouse in us the desire to return to past times, whether we experienced them or not. Rather, it seems to suspend time in order to envelop us in an atmosphere of here and now charged with an expansive vibration generated by each work, each approach, each visit to the exhibition. Time itself becomes multiple due to this back-and-forth, which breaks the thread of ordinary temporality: the detemporalization of time.

Making our way around the full exhibition would take at least eight hours, but we need only a few moments in contact with the works, so clear are they, to access ideas about the relationship of power and tension between image and sound, as well as those about the visualization of music and musicalization of the image. By putting us in constantly renewed states of perception, the exhibition becomes both single and multiple; each work becomes single and multiple. And it is here, in this playing with time, in this idea of infinitude, that we can find the key to an art that seems to foresee – if not construct – its future.

About the Extended Body and Connections. The layout of theexhibition, without claiming monumentality but absolutely true to the “white cube” precepts of neutrality and contextual refinement, offers a path that is free but not arbitrary. At first glance, momentarily, we don’t find the promised idea of relationship between sound and image, as the works seem to function only in their visual dimensions. It is through our action that they become complete: by connecting with each one through corded earphones lent out at the entrance, which become an extension of our body, we integrate the sound dimension into our experience. Thus, as we stroll through the exhibition, we, as body-visitor-spectator, connect with one work and then the next – a little like the characters in the film Avatar – activating multiple worlds that are deployed and separated from the rest of the world. As body-visitor-spectator, in our connection with the work and the exhibition, we become multiplicity.

Organized into five distinct bodies of work, the exhibition opens on a sort of preamble in the antechamber of the main gallery. On the wall is a composition of screens showing films. In a showcase is a grouping of printed images that hail back to the epoch of great inventions related to the moving image and sound, highlighting the experimental nature of the first rapprochements between art and the worlds of sound and moving images. This preamble in a way presages the hybrid and heterogeneous nature of the exhibition. Most of the films on view date from the 1920s. One is Marcel Duchamp’s Anemic Cinema (1926) (signed by his alter ego, Rrose Sélavy), which shows, in alternation, circular forms caught up in a circular motion and texts spiralling counter-clockwise. Another experimental film, directed by Viking Eggeling, could also be associated with the Dadaist current. Symphonie diagonale (1924) is composed of square and circular figures that grow, multiply, appear and disappear, and are juxtaposed in an almost hypnotic sequence, forming visuals that could be compared to those that produce both fractals and typical Art Deco images. These two works, and the grouping of which they are part, are accompanied by the Charleston music played during an excerpt of Ernst Lubitsch’s 1926 silent film So This is Paris. In addition to serving as a preface to the exhibition, this grouping testifies to the fact that early artistic experiments in the field of the moving image, in synchrony with the avant-garde movements of the time, sought to represent nothing but themselves.

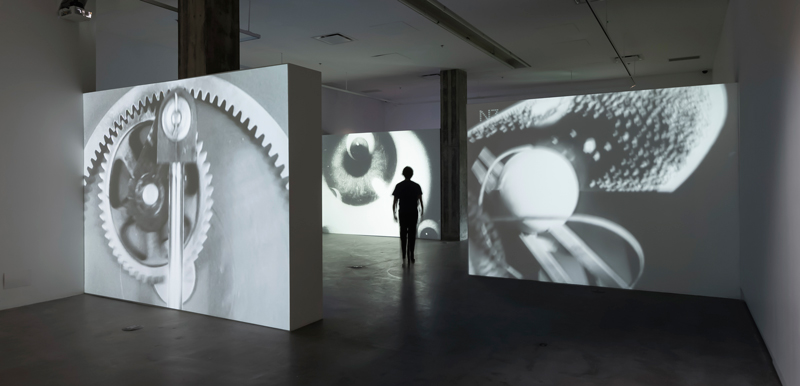

When we cross the threshold of the main gallery, we discover seven projections set up to offer a free, zigzagging path. The first one we encounter is a powerful film by René Jodoin, made on a computer in 1984, whose title, Rectangle et rectangles, refers directly to the idea of the single and the multiple. This kinetic, psychedelic work presents a series of geometric forms in contrasting colours, with percussive beats created by sound artist Louis Hone. This music also plays the role of sound background throughout the gallery from time to time.

This first film is placed in dialogue with the two others, which are in colour. Optical Poem, created in 1938 by German artist and director Oskar Fischinger, is composed of two-dimensional forms in motion, assembling and dispersing, producing repetitive motifs that seem to follow grouping modes such as a school of fish, a flock of birds, and a swarm of insects. Their growing momentum comes to saturate the screen in a superimposition that matches the rhythms established by Franz Liszt’s second Hungarian Rhapsody. Fischinger considered this film, produced in analog, a scientific experiment with the goal of visually transmitting the mental images produced by music.

The colour section concludes with Synchromy (1971), a sound film by Norman McLaren for which he composed a piece that truly foregrounds the notion of tension between image and sound. Using synthetic sounds, McLaren illustrates the interplay of subordination and domination performed by music and moving image. Here, the sound is not simply accompanying what we see, it is interacting in consonance with the visual, accentuating the expansive nature of the work, and potentializing the deployment of the multiple. This film is perhaps the masterpiece of the exhibition – to be understood as not central figure or root, but as line of convergence – because it highlights a pivotal moment between modernity and postmodernity (assuming that such a moment can be pinpointed).

After these colour works come four black-and-white sound films that are heterogeneous pieces created in different epochs. They propose a temporal short circuit, a kind of deterritorialization from which other explorations escape and combine. One standout is Hans Richter’s Filmstudie (1926), with music by Darius Milhaud. A sort of visual folly, it combines, in layers, a repertoire of repetitions that navigate between figuration (eyes, birds) and abstraction (circles, triangles, light beams). In dialogue with this work, Ralph Steiner’s Mechanical Principles (1930), with music by Eric Beheim, illustrates the oscillations and transfer of industrial mechanical parts and clockwork mechanisms, which, to the undulating rhythm of a tango, become hypnotic machines. Finally, at the back of the gallery, we find Martin Arnold’s Passage à l’acte (1993), a convulsive re-editing of the movie To Kill a Mockingbird (Robert Mulligan, 1962) in which the sound is transformed into a sharp pounding.

The group of works in the “abstract cinema” section shun any idea of meaning and open a field of interconnections the occurrence of which is inscribed not in one reality, but among several: fragmentary figurations, incomplete geometries, unstable objects, broken sounds, interrupted resonances.

Ruptures and Ramifications. In another movement toward deterritorialization, other paths veer off rhizomatically and other lines of convergence immerse us in worlds that we may not have expected to see in the extension of the main body of the exhibition. Another point of view on the relationship between the moving image and music is offered in a gallery in which eighty videos made between 1958 and 2019 are screened without interruption. The videos, which fit within the narrative structures of cinema, are, by their very nature, loaded with signs and significations, and the images (detached from their synchronization, like a silent film) serve the music industry. Another rupture: in a small gallery equipped with a monitor and a seating booth, the exhibition reaches out to and includes youth audience, through a careful selection that includes nine animated films, all produced between 1977 and 2019 by the National Film Board of Canada, in which sound plays a crucial role in the construction of fictional worlds, narration, and tone, often humorous.

Finally, among this seemingly infinite play of ramifications, one gallery hosts an installation designed and produced specifically for the exhibition, whose raw material is composed of 1920s silent films. Les marges du silence/ghosts along the way (2020), by Michaela Grill and Sophie Trudeau, is divided into several elements: a large screen on which are projected isolated images; a mosaic-like arrangement of monitors showing diverse scenes; a monitor on which are presented excerpts of written dialogue detached from their context and a sound creation by Trudeau, composed from detached and remixed sounds. With its analytic approach, this installation offers, in a way, a synthesis of several propositions offered in the exhibition.

Multiplicity and Dematerialization. Although the exhibition uses physical mechanisms, most of the works presented do not depend on materiality to impose their presence. Aside from a field of interconnections between visual and sound architecture, Les années musicales: 1920–2020 asks us to apprehend the world through other dimensions to inhabit the multiple. It’s an exhibition of dematerialization, flux, rupture, movement, and ramification, exploring the world of the liminal and indeterminate. It distances itself from the rigid structures imposed by ideas of essence, nature, and certainty. An art of articulation, interstice, transition, and infiltration. An

exhibition of the single and the multiple. Translated by Käthe Roth

1 Les années musicales : 1920–2020, Vox, centre de l’image contemporaine, August 18 to October 31, 2020.

2 Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, trans. Brian Massumi (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987), 6 (emphasis in original).

3 See Marie J. Jean’s essay in the pamphlet Les années musicales : 1920–2020 (Montreal: Vox, centre de l’image contemporaine, 2020).

4 Brian O’Doherty, Inside the White Cube: The Ideology of the Gallery Space (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1999).

In 2013, Edward Pérez-González earned a PhD in architecture focused on a postmodern conception of museums and, more specifically, on Deleuzian philosophy. He has curated numerous exhibitions in Venezuela and Brazil. He was a member of the curatorial laboratory of the Leopoldo Gotuzzo Art Museum affiliated with the Universidade Federal de Pelotas, in Brazil, where he is a guest researcher. In recent years, his research has focused on contemporary painting, architectural theory, and curating exhibitions.