[Summer 2021]

John Akomfrah, Vertigo Sea

By Jill Glessing

The Design Exchange Trading Floor, Nuit Blanche, Toronto

2.10.2016

Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal

10.02.2021 – 4.04.2021

The sea, wild and wet, the womb that bore us, from which we slithered eons ago. We return to that birthplace – for crossings, sustenance, profit, and pleasure. Even as mysteries still dwell beneath those expansive liquid surfaces, our anthropocenic impulse seeks to control and, perhaps, destroy it.

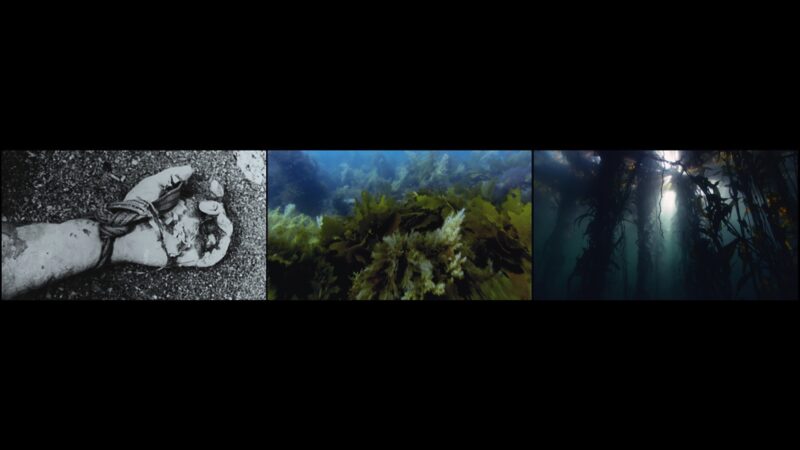

John Akomfrah’s three-channel film essay Vertigo Sea (2015) provides an immersive environment in a panoramic span – a powerful montage of overlaid, overlapping still and moving images and sound. The words “Oblique tales on the aquatic sublime,” appearing on a solid blue field, open the film, serving as subtitle or description. It is the first text to punctuate Akomfrah’s sound-image orchestration and contribute to the film’s thematic grazing. Rhythmic audio pulses, suggesting a clock ticking or a hammer hitting, accompany and strengthen the idea of “aquatic sublime” – we are asked to consider the longue durée here: the primordial brains of whales, the centuries of fertile abundance before humans began their industrial carnage. In the central image of the film’s first triptych, framed by two overhead views of the great blue sea, a hand cradles a clock. This is a universal story: the sea as site of history, of beauty and bounty, which, wrought by human forces, becomes a scene of disaster. This watery basin, once brimming with life, becomes, over human time, a graveyard in which our crimes are buried. Vertigo Sea offers a memorial for the enslaved, trafficked, and migrant bodies passing through it and centuries of pillaged sea life.

The installation’s large scale, combined with the cumulative effect of stunning and disturbing imagery, kindles responses of awe and humility. Despite its mostly historical content, it prompts viewers to consider their own contemporary relationship with the savagery perpetrated within and against that watery paradise. The imagery in Vertigo Sea is sourced primarily from official archives, including the BBC Natural History Unit and the British Film Institute; its soundtrack marries a haunting composition by Tandis Jenhudson with recordings of roiling waves, raucous bird sounds, low whale calls, and human song – sea shanties merging with operatic strains – as well as voice-over narrations culled from literary, philosophical, and popular writings. An elegiac undercurrent of lament and mourning builds cumulatively as these elements mingle throughout the film.

Ghanaian-born British artist Akomfrah developed his creative process – dialectical montage inspired by politically engaged Soviet filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein – during his many years making post-colonialist activist films within the Black Audio Film Collective. Vertigo Sea pushes these interests further, into broader political, environmental, and global critiques.

Historical references to sea tragedy and destruction surface and resurface throughout the film: the contemporary refugee crisis (the film was inspired by the 2007 sinking of a migrant boat in Mediterranean); the triangular African slave trade in which captives avoided servile labour on colonial lands only by drowning at sea; the crossings of the sea by Britain and other nations as they colonized and exploited other peoples and places; the modern industrial massacre of sea creatures through whaling and fishing for human consumption; the sport-hunting of polar bears; the sea as disposal site for disappeared Argentinian and other political dissidents; the mercury-poisoned water that debilitated humans, fish, and animals on the coast of Minamata, Japan; the atomic explosions in Bikini Atoll performed as US military experiments; and all this partly overwritten by the wondrous beauty and power of the sea itself – giant aquamarine curls of waves and undulating sea creatures.

The film’s aesthetic and philosophical references encompass a range of visual and written texts. Because the sea was thick with nefarious traffic in the nineteenth century, Romantic artists painted scenes of maritime tragedies. Théodore Géricault’s painting Raft of the Medusa (1819), depicting victims cast off by an incompetent captain, is reimagined in recent footage of overladen migrant boats in the Mediterranean. Staged scenes of drowned African slaves washed ashore reference another historical atrocity, recorded by J. M. W. Turner’s The Slave Ship (1840), in which 132 captives were thrown overboard from the slave ship Zong so that the ship’s owner could collect the insurance monies. Reminiscent of Caspar David Friedrich’s paintings that express the sublime, staged scenes show solitary Victorian figures of interchanging identity – man, woman, black, white – naval commanders and abandoned lovers – gazing out into the sea. Literary references include excerpts from Herman Melville’s novel Moby Dick (1851) and Virginia Woolf (who famously died a watery death).

With this surfeit of dark allusion, Akomfrah risks casting his viewers into ruin, like the shipwrecks pictured here. But that historical weight is buoyed by affirming and abundant scenes showing the sea’s majestic beauty and the vibrant life that still thrives within it.

Jill Glessing teaches at Ryerson University and writes on visual arts and culture.

[ See the magazine for the complete article and more images : Ciel variable 117 – SHIFTED ]