[Fall 1994]

by Claire Gravel

William Eakin is interested in what he refers to as cultural shards, or objects that inform of a popular culture whose aesthetic values are looked down upon by people with “taste.”

Deeply marked by the austerity of Walker Evans’s universe and by Robert Frank’s The Americans, Eakin says he is “drawn to their ability to see things that weren’t being acknowledged in American culture.” Known for an oeuvre inscribed with sociological ramifications, he is researching and developing an iconography which, according to critic Robert Enright, resembles a “marginal archeology.”

While working on Mighty Niagara (1980-84), Eakin discovered “broken memories” in a small shop. Isolated within the image, these shattered souvenirs express the very essence of the artist’s discourse.

With My Father’s Garden (1983), the close-up images of an abandoned vegetable garden recall a memento mori. In Where Distance Is Measured in Time (1983-85), with its Inuit rituals, and their humble offerings to the dead, Eakin’s poetic language is confirmed. There is a change in the photographic approach. The image is constructed. Miniature objects (TVScreens, 1990) are displayed in ironical settings.

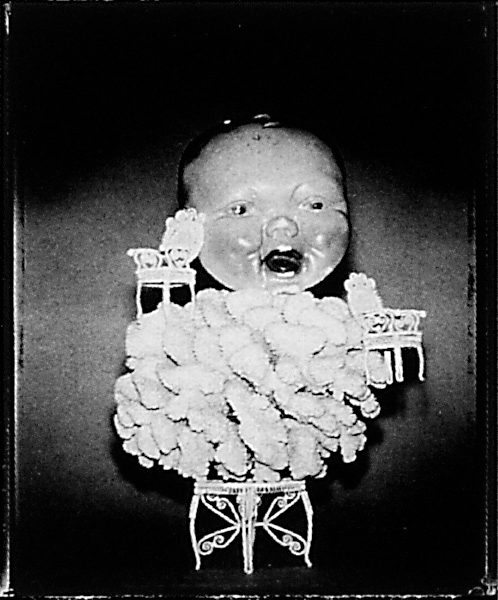

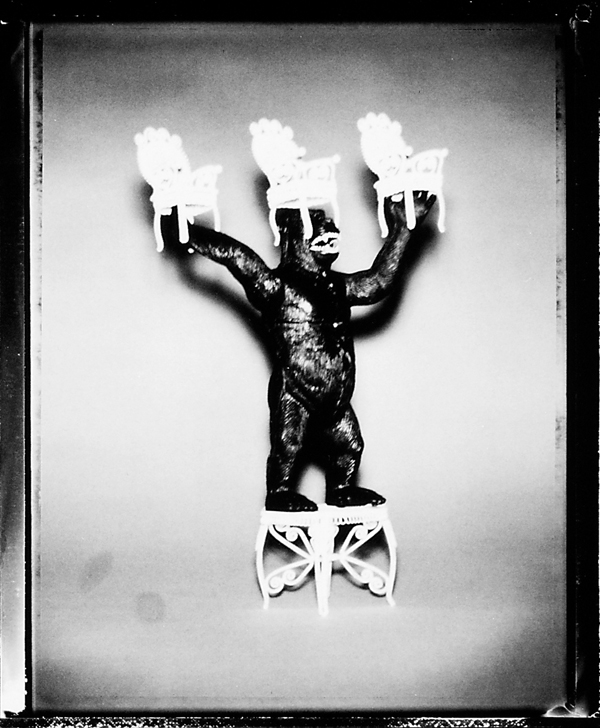

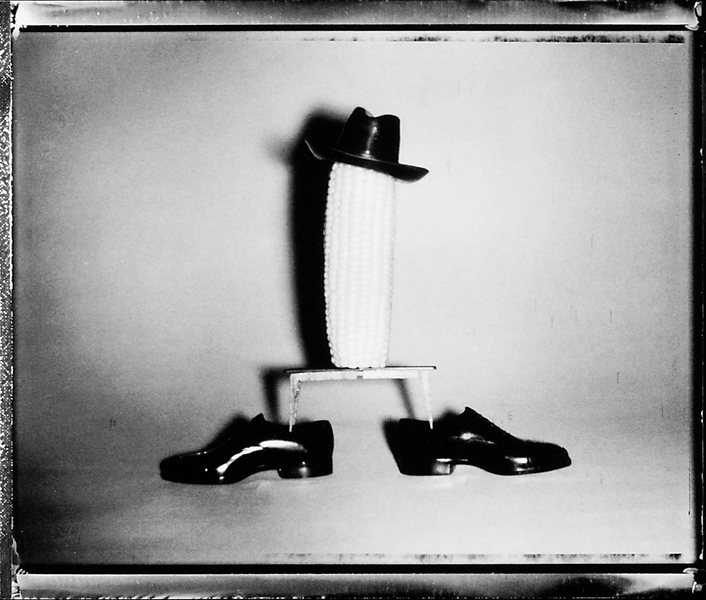

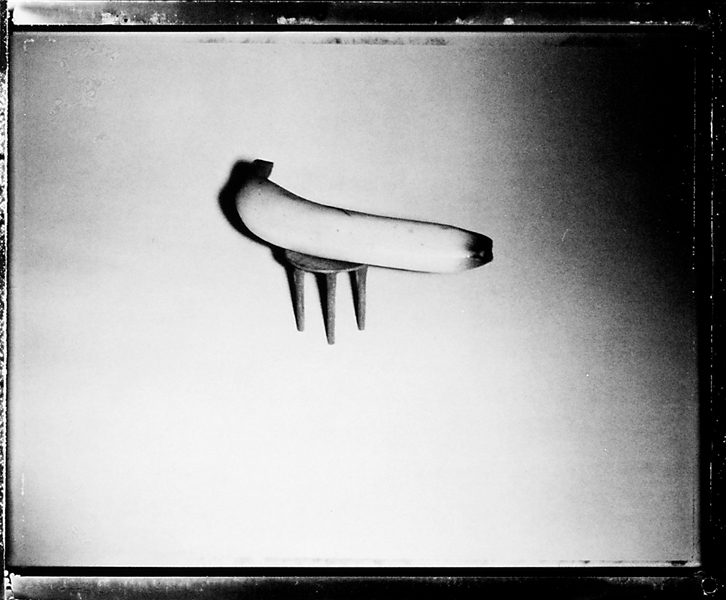

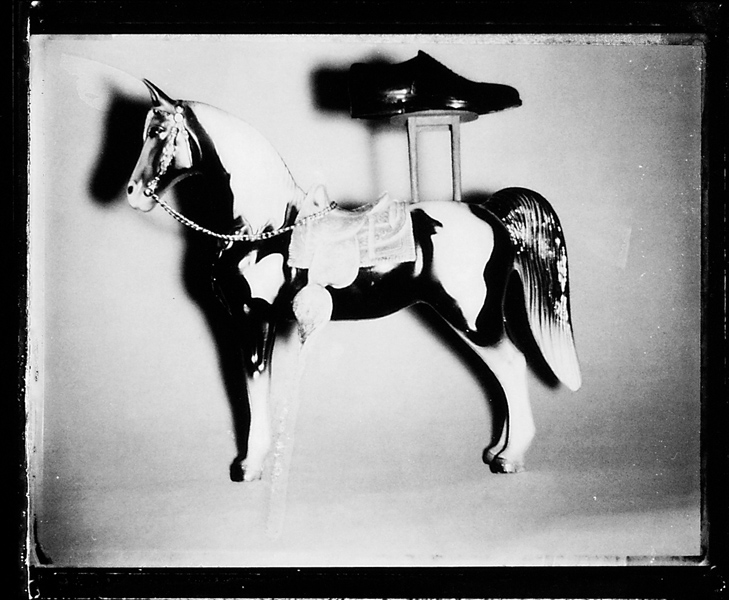

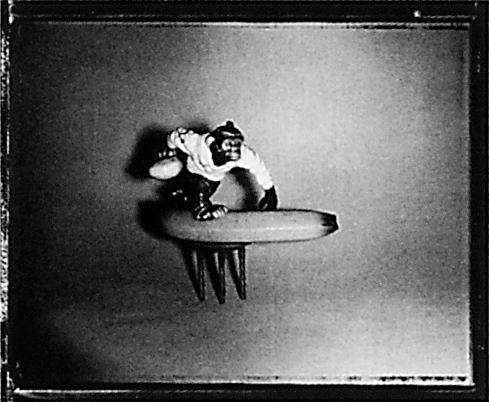

The photographic process used in the Tabletop series (1992) consists in working with Polaroid film plates. The 4×5 inch plates produce a negative film along with the familiar positive print. The final image is surrounded by small imperfections, and the margins created by the physical structure of the plates resemble frames brushed by light. We become attentive to even the slightest shading, scratching the surface of these delicate shapes as specks of light.

Both the generic title and the unidentified location of Tabletop convey a sense of distance with regard to the setting of the objects which, it is suggested, is relative: a table is merely an indifferent support for an assortment of things that “top” it.

They are derisive monuments, plastic figurines, knick-knacks and vernacular souvenirs that the artist has long since been collecting as treasures.

Tabletop redefines the configuration of vision by dislocating origins and memory, by working with the unexpected, by de-contextualizing, and by playing on the deferred meanings of objects redoubled.

Is this to be understood as an aesthetic of “making strange?”1 In fact, a previous series of Eakin’s is entitled Strange Attractor. It discloses the convulsive beauty of fortuitous encounters. Are Tabletop’s components not then surrealist?

Objects found in flea markets become akin to those that appear through “objective chance.” They are emissaries of the exterior world, and in them the artist seeks a particular type of gratification. One may remember the photograph Man Ray took of a spoon found in a flea market in 1937. The spoon was adorned with a small shoe, and André Breton believed it to be an experience of reality as representation of the “Marvelous”.2

In Tabletop, however, Eakin does more than simply document the found objects, he works with them, plays on their ability to embody and to become décor. Once assembled, they describe a type of imago mundi. The shot is always the same: full-length portraits of tables, legs included, adds the artist. A certain sense of formalism appears to surface through these objects: their very repetition creates a recurring motif, and the likeness of the functions they occupy in diverse images creates yet another pattern. We are reminded of Bertrand Lavier’s sculptures,where a refrigerator sits upon a strongbox. With Eakin, though, the thought process goes beyond the nature of the supporting base. Similarly, although his objects seem to share their cultural origins with those used by artists Jeff Koons and Ashley Bickerton, Eakin’s work differs in that it is void of any simulation mechanism.

With but a few objects grouped in the centre of a uniform background, Tabletop’s composition is rigourously bare. The internal arrangement of its components is nonetheless spectacular. Standing on a banana, a chimpanzee tosses a ball toward a nest of roses. Meanwhile, sporting unusual hats, the Venus of Milo and King Kong make an appearance on either side of a pine cone standing erect in a patent shoe. The tables flaunt outrageous pairings that metaphorically suggest frantic and unbridled consumption. Somehow, as if by magic, these “vulgar” objects -glowing beneath their halo of light – are invested with disconcerting symbolism.

In these instantaneous sculptures, resistance to meaning quickly gives way to gentle folly. Their interchangeability is at once deceiving and amusing. Denying the image’s unidimensional stronghold by presenting themselves in detachable units, they deceive; giving free range to our imagination by affording countless possibilities of surprising, if not comical, groupings, they amuse. As a consequence, the very notion of a work of art is put into an endless chain of perspective.

William Eakin subscribes to what Abraham Moles defines as the “art of bliss”: kitsch, linked here to childhood imaginary. Indeed, his work abounds with made-up games and bewildering stories told in but a few words.

Tabletop is autobiographical. It reveals both the compulsion of the collector and the psychological investment of the author, palpable in the images’ preciseness.

The seeming incoherence of the objects’ varying scales serves to accentuate the fabricated, concocted, quality of the images. In a world where the historical subject has been set aside as a “falsified performative discourse” («discours performatif truqué», Barthes), William Eakin comments on the fragility of our desires.

Translated by Jennifer Couëlle

1 Simon Watney, “Making Strange: The Shattered Mirror” in Thinking Photography, London, Macmillan, 1982, pp. 154176.

2 See Rosalind E. Krauss, “Photographic Conditions of Surrealism” in The Originality of the Avant-Garde and Other Modernist Myths, Cambridge, The MIT Press, 1986.

Professor of art history, critic and curator of present-day art, Claire Gravel holds a doctorate in esthetics from the Université of Paris-X (1984). She has published numerous articles about photography in the Montreal daily Le Devoir (1987-1991), as well as in specialized magazines: Flash Art, Les Herbes rouges, Vie des Arts and CVphoto.

William Eakin was born in Winnipeg, Manitoba, in 1952. He studied at the Vancouver School of Art from 1971 to 1974, and at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts of Boston from 1974 to 1975. His work has been presented in numerous solo exhibitions, amongst which TV Screens at the Winnipeg Art Gallery in 1991, and My Father’s Garden, which travelled throughout Canada. He also particpated in large group exhibitions such as Theatre of Objects (CMCP, 1990) and Beau: A Reflection on the Nature of Beauty in Photography (CMCP, 1992). His work is part of the Canada Council Art Bank as well as other major Canadian collections. William Eakin lives and works in Winnipeg.