[Winter 1996-1997]

The odour of photographed things is tenacious and disconcerting: acrid, tepid, tart, icy, fetid, chemical, hygienic, aseptic, nauseating.

An odour of “miserable humanity” in an auditorium, a waiting room, a dance hall, a bourgeois living room, an observation room, a treatment room, a shooting gallery, a classroom, a hairdressing salon, an exhibition hall, a registry office, a municipal council chamber, a demonstration booth, a model home. A typical case of olfactory hallucination.

by Catherine Pomparat

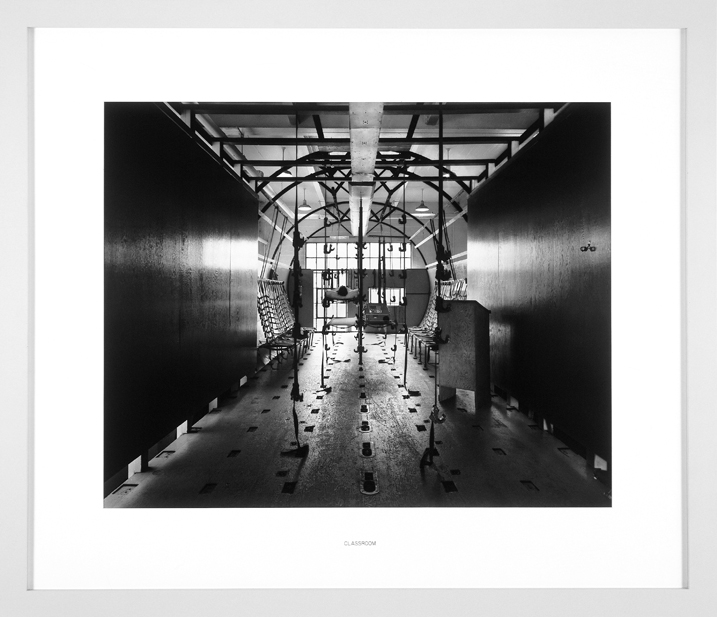

A map of Borgesian disproportion covers the floor. It is a simulated military territory, scaled to fit a lecture hall: at the back of the auditorium, two black parallelepiped cavities break up the symmetrical arrangement of chairs and define the site of training. These two black holes, looming lopsidedly on either side of a clock, are passages for images, wall openings for projectors. But there is no screen to receive the images and no one to look at them. Only the viewer faces the auditorium that is thrust forward so strongly. The photograph, in its black formica frame, composes a frontal, irrepressible invasion, devoid of human presence.

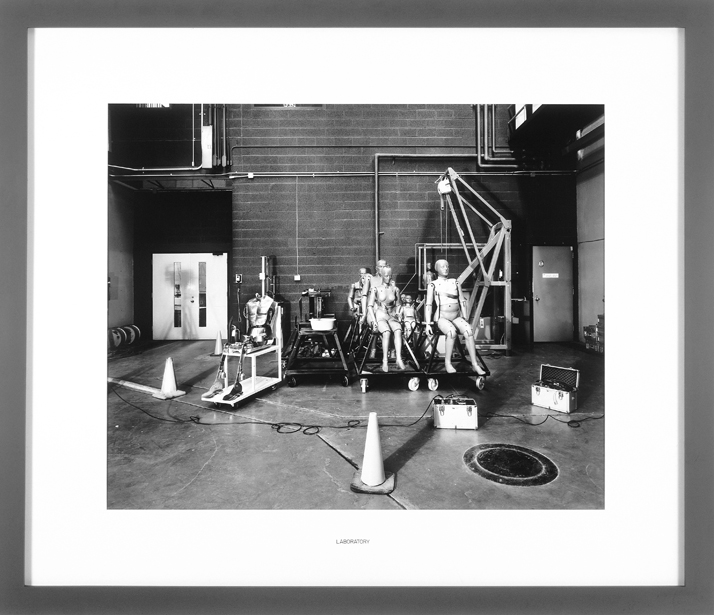

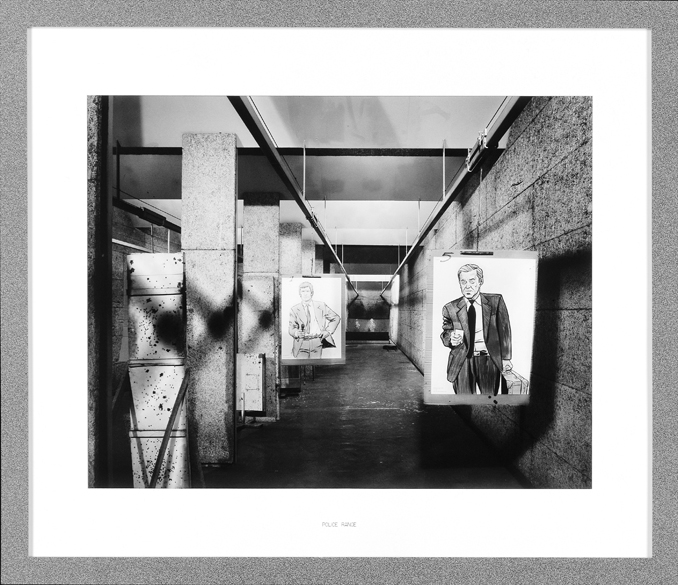

The photographs are presented in simulated-marble, simulated-granite, simulated-colour formica frames. Coloured mats are inscribed with the name of the type of place photographed: auditorium, living room, men’s club, classroom, waiting room, spa, laboratory, factory, exhibition hall, shooting gallery, observation room. The photographs bear no other geographical or historical identification of the site. Perhaps this boat-shaped desk is in a council chamber of some European provincial municipality; or perhaps not. Nor are the photographs dated. They are apprehended just after the instant the shot is taken, a temporal limit imposed by the camera. A persistent attitude with no instantaneity. The artist works with a large-format camera, an awkward instrument on a tripod, which requires her to drape a black cloth over her head when she takes the picture.

There is no dominant historical truth, no anecdote framing the event, no highlighting of spaces: these photographs are in the plural infinitive.1 The infinitive is the virtuality of action, of thought, of feeling, without the actor that makes it possible. The plural is the mark of the multiplicity of things in the world. There are many things that are common – that is, ordinary and shared. At a time when all things are seen at the same time, constantly and everywhere, where public and private spaces are superimposed upon each other, these photographs reveal our behaviours from our particular ways of living in shared and common places, and give shape to an invisible, violent, and symbolic reality.

One photograph, framed in false marble, shows a couple of cardboard silhouettes in the living room of a model home: a man reading his newspaper, a woman reading her book, frozen, on either side of a green plant and a lit floor lamp. A framed mirror on the left-hand wall reflects the out-of-frame windows looking out on leafless trees. More than an anthropological approach to domestic space, the conjugal bond reduced to the image of a couple sitting in the vacuum of their relationship recalls Perec’s definition of the verb “to live”: “Passing from one space to another trying as hard as possible not to bump into anything”2 – as in the chronological declension of matrimonial relations, as in the sequence of breakfasts between Kane and his first wife in Orson Welles’s film Citizen Kane.

Photographs empty of human presence. The emptiness is not absence: there are substitutes for people, substitutes for nature, and things in anthropomorphic shapes – things, not objects, since their functionality has become relative. They are there no longer because they are useful and effective, but in order to participate in the ambiguity of things as represented since Duchamp, Magritte, Broodthaers. This is not a treatment room, a conference room, a shooting gallery; it is a representation of art. The things represented are deterritorialized, removed from the everyday world to the world of art.

“Storage alcoves become altars of gothic architecture, wallpaper in a bourgeois living room and a waiting room resemble neoclassical frescoes, the organized space of a treatment room evokes the pictorial structure of a Vermeer work, painted silhouettes stencilled on various walls recall Pop Art, Marcel Duchamp’s ready-mades are everywhere, Kosuth’s clocks are seen often, Flavin’s lights and Magritte’s clouds are not infrequent, entire sections of walls covered with photographs of men refer to the work of Gerhard Richter, rational and ordered work spaces from Guillaume Bijl’s installations can be seen, Artschwager’s formica pieces are omnipresent, and the ghost of Beuys comes through the blackboards.”3

The world is a museum and the things in the world are ready-mades. Maybe not the world, but particular places in the world, constructed interior spaces, characterized by their social function: greeting, waiting, meeting, learning, training, resting, parties, therapy. . . . The house and the booth are the sites for these functions. An ordering of mute things expressed by their position, their disposition, their composition, their exhibition. There are rows of tiles, photographs of men, headdresses, targets, model busts, wigs, trophies, silhouettes of painted birds, chairs. . . . There are settings of furniture, curios, cushions, Christmas wreaths, fur blankets, animal skeletons, hats, real plants, fake trees. . . . There is the structure of neo-Mussolinian columns in an aquatic space, there is the prison-like architecture of a treatment room. . . . There is no one there.

The normalizing processes of society – the sites of production of social cohesion, the societal frameworks, control, training, therapy – engender the organization of spaces, induce modes of behaviour. By modifying the links between the visible and the invisible, these photographs figure the spaces, cut up the fields of experience, compose the relations between people, make explicit what photographic reality proposes implicitly. The raw material of things of the world is transformed into found things, found installations, photographable ready-mades, by the appropriation of points of view and framing.

The acceptance of the notion of framing, here, is double: the irreducible framing of the photographic act – but also the frames, the no less irreducible accessories to these photographs. Far from a redundancy, frames establish both a proximity to and a distance from the things represented: proximity in the sense that they are what they pretend not to be – frames. The frame rules the position of the photograph, legitimates its presence as a work of art in the space where it is exhibited. Distance, in the sense that they pretend not to be what they are: objects. Lynne Cohen is trained as a sculptor, and the work of the artist is also to make objects and be confronted with the physical aspect of things.

The physical, visible aspects of things also provide logics, principles, laws that standardize photographed spaces: alignment, symmetry, scale (miniaturization, gigantism), geometrization, numbering, measuring, and so on. More than a definitive order, these photographs make visible a defined order: ours. The halves of the mannequin are aligned, side by side, on factory tables, four headless busts are placed on the ground, the lit fluorescents on the ceiling lend rhythm to the space, and all the figures are identical. The perfect flattening of faces and bodies to represent a single possible model of man. A row of singing, playing angels from a Hans Memling painting. Between order and disorder, these photographs bring to light previously unexposed correspondences between things that overturn the usual classifications. Phallus-shaped balloons in a party room. Painted fish on the wall of a recording studio.

“Things don’t seem to be what they are: presentations of exotic sites in murals seem to be overgrown bonsais, vacation hotels look like psychiatric hospitals and psychiatric hospitals like retirement homes, weapons look like toys, windows imitate mirrors4.”

Neither true nor false, or perhaps false truth: there is nothing but a screen without an image, in an empty room with walls of stainless steel covered with mirrors. From the moment that things are photographed beside each other, they inevitably have a connection and a meaning. The task assigned to these photographs is to show that there is no inevitability in all this. Things are accessories of daily life that hold the actor and the action together. The photographs take account of this precarious balance. “The photograph is an artifice that allows for no trickery5,” the effect of art and lies, absence and presence, a generalized oxymoron. The blackboard is this “between two inscriptions” that characterizes the photographic process, and its hidden writing haunts Lynne Cohen’s photographs: palimpsest, memory of eye and mind, cosa mentale, emblematic figure of photographs in the plural infinitive.

2 Georges Perec, Espèces d’espaces, Paris, Galilée, 1974, p. 14.

3 Lynne Cohen, conférence, École des Beaux-Arts de Bordeaux, 26 avril 1993.

4 Lynne Cohen, op. cit.

5 Lynne Cohen, Entretien avec Tio Bellido, FRAC Limousin, 1992, p. 77.

Lynne Cohen , an American by birth, lives and works in Ottawa. A professor of visual arts at the University of Ottawa, she is also pursuing an international art career. For more than twenty years, her works have been exhibited regularly in many countries and featured in a number of publications

Catherine Pomparat was born in Bordeaux, France. She has been a professor of “general culture” in the Visual and Audiovisual Communications Department at the École des Beaux-Arts de Bordeaux since 1978. For the last four years, she has led a workshop on the photographic research into “common things.” It was within this workshop that she had her encounter with Lynne Cohen.