[Summer 1997]

By Russell Keziere

We live in a time when all communication happens under a cloud of erasure. We are conditioned instinctively to call into question vested interests and hidden, undisclosed motives.

In this cloud of postmodern skepticism, words and representations are equivocal – until proven innocent. We negate before we can feel safe to affirm.

Consider “identity”: what a strange, antique concept. The concept of identity is like a nineteenth-century equestrian statue. It is heroic, implausible, ironic, and largely laughable. It is something to be pulled down, left to the pigeons.

There are those – such as Le Pen and other racists – who still promote blood nostalgia for these statues. But one suspects that deep down even they know that they are acting out a fetish. Although we are anaesthetized out of self-defence, we are quite good at adapting. In fact, we are becoming sophisticated and comfortable within this via negativa. The question is no longer whether we can survive the liberation of negation and erasure, but what do we do when we get there, and what we mean when we say “we.”

Arnaud Maggs’s Notification is a profound and elegant commentary on this issue of life and history under erasure. The Notification series, like much of Maggs’s previous work, is based on a found object that is zealously pursued until it becomes a collection. In this case, the source object is a mailed death notice, sent by the recently bereaved to those who need to be informed. Most of them were mailed to addresses in France in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

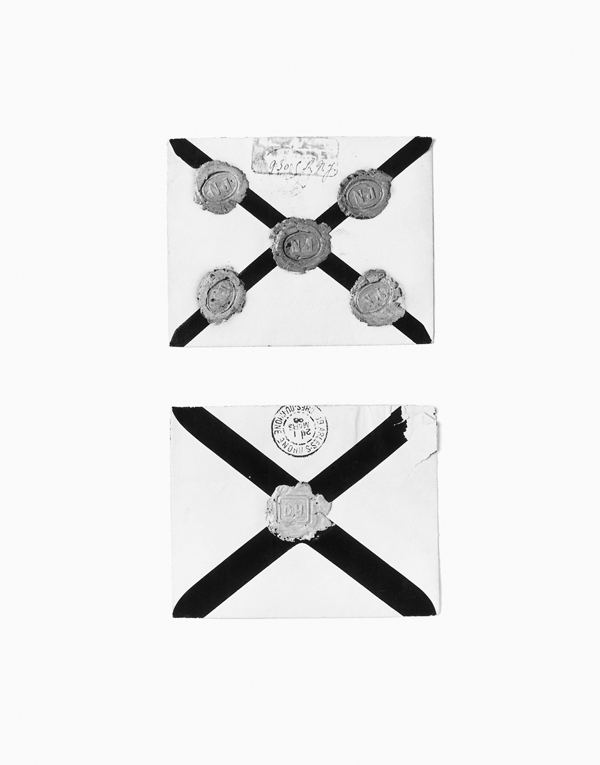

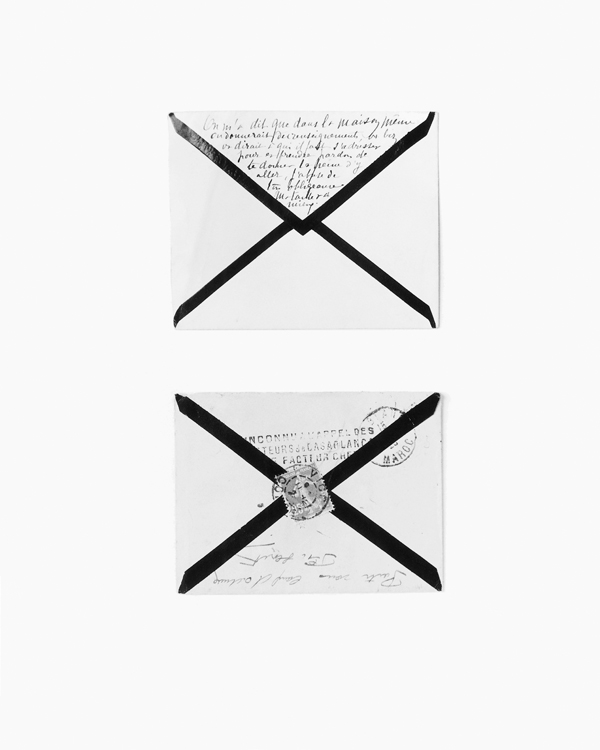

The notification itself is generally a small envelope, distinguished from all others by a large, black “X.” Until the envelope is opened, one cannot know who died. One may suppose, by virtue of the return address. But one cannot know.

Many decades later, we know even less. Maggs has made colour photographs of the backs of these notifications, framed them, and arranged them in a grid on the wall. The series is evolving and will have multiple incarnations. In the first installation of the Notification series at the Susan Hobbs Gallery in Toronto, for example, Maggs installed them floor to ceiling, eight deep and twenty-four wide.

When I first saw this installation, the graphic effect of the rows and columns of Xs delighted me. There is something comforting in repetition; there is something familiar about patterns.

Slowly, however, the import of this collection comes to the fore. The individual envelopes are enlarged, bringing the specific markings and postal impressions into focus. We cannot avoid their particulars, and this pulls us out of the pattern and back into history. Someone has died but we cannot know whom, the identity is erased, the memory is embalmed within the photograph. We cannot turn the envelope over; the wound of their historical opening has been sutured closed within the photograph. Some of them have been ripped apart, some carefully and precisely opened with a letter opener. Some have incidental scribbles added to the envelope. Some international notices delivered during World War One are marked “saisi par la censure” (seized by the censor). And others have been registered, filled, sealed with colour-coded wax, and imprinted with an authentication code. A human body, a personal history, and a word: these are all just envelopes. They are censored, opened, and emptied of their content against their will.

The Notification series is a contradiction. One would think that a mass of death notices would render one numb, uncaring, as if one were watching a late-night television report of some far-off atrocity. But there is no sentiment of grief in Notification, no lament, no personality, and no nostalgia. The identity of the deceased is under erasure at the very moment that it is, perhaps, most recognized and identified. The relentlessness of the series is like a mantra of remembering at the very moment of forgetting.

Maggs is neutral. He does not, and does not need to, say anything. His is a full-frontal documentary abstraction: historical moments strung together into a pattern, like one of those computer-generated fractal images that come from massive amounts of random data. Unlike a chaos-inspired pattern, however, Maggs’s work allows us the privilege of specificity. This envelope was sent from Arles, arrived at the Dijon Station on April 23, 1891. This envelope was unquestionably torn open in haste and likely in an agitated state of anticipatory grief.

Maggs’s obsessive series of photographs combines the stroke of Zen calligraphy with the structuralism of the Annales group. His collection of death notices is a “thick description” of the litany of personal histories that passed through the post offices of France. The ego-fact of any individual is irrelevant, the product of desire, something that comes and goes. And yet every specific ego-diary is important, it is the true stuff of history. We make random traces on history; but they are full of consequence and interconnection regardless of how unpredictable those consequences and connections may be.

Calvin O. Schrag describes this phenomenon as “convergence without coincidence.” Instead of subscribing to a single, universal self, we have a transversal self. Borrowing from Deleuze and Guattari, Schrag observes, Harmony and unity cannot be achieved via a vertically ordered and hegemonic decision-making arrangement that simply subordinates the lower to the higher. Nor can, of course, decision making be left to the autonomy of horizontally serialized groups. What is required is a transversal ordering and communication that is achieved through a diagonal movement across the groups, acknowledging the otherness and integrity of each, while making their requisite accommodations and adjustments along the way. Such is the dynamics of transversality, striving for convergence without coincidence, skirting the Scylla of a hegemonic unification while steering clear of the Charybdis of a chaotic pluralism.1

Standing in front of Maggs’s serialized Notification, we see no dominant horizontals or verticals. These are clearly negated by the crossed diagonals of the repeated “X.” As a result, each notice is anonymous yet personalized. They converge against a background of transcendent finitude. We come away from Notification humbled, quiet, respectful, and aware. We are, also, a little less sophisticated. We cannot, however, comfortably regress into a humanism of ego-fetish. The statues of Identity are not resurrected, dusted off. And we cannot casually surf our way out of the hypertext web of human history.

Instead, Maggs helps us to acknowledge the traces that an individual leaves in the particle accelerator of society and history. It is in and among these traces that we can see a new pattern for connectivity.

1 Calvin O. Schrag, The Self after Postmodernity, New York, Yale University Press, 1997, p. 132.

Arnaud Maggs lives and works in Toronto. His work has been exhibited in many galleries and museums throughout Canada and in other countries. Most recently, he has participated in the exhibitions Double vie , double vue at Fondation Cartier (Le Mois de la Photo à Paris, September 1996) and Obsessions: From Wunderkammer to Cyberspace at Rijkmuseum Twenthe (Foto Biennale Enschede, Netherlands, 1995). The Notification series was presented at the Susan Hobbs Gallery in Toronto in 1996.

Russell Keziere is a writer and critic living in Toronto. Between 1979 and 1989, he was publisher and editor of Vanguard magazine. Since 1990, he has been engaged in technology marketing and consulting. He is currently editor of Electronic Composition and Imaging and Print on Demand Business Canada.