[Winter 2003]

The resulting book, Places Lost: In Search of Newfoundland’s Resettled Communities, gathers some forty images reproduced in duotone, along with many vintage photographs of the communities as they were prior to resettlement. In addition to some history, the book explores the use of photography to convey the loss of place, and the ways in which objects acquire significance through the recovery of their past lives.

by Scott Walden

During the 1960s, you could look out over the ocean in Newfoundland and see houses floating by. Natural disasters weren’t the cause; governments were. Soon after Newfoundland joined Canada in 1949, the governments of Canada and the newly formed province resolved to centralize the island’s population, moving people from isolated outports to larger “growth centres.”

Rather than abandoning their homes, many resourceful Newfoundlanders winched them down to the shoreline, attached empty oil drums to the foundations, and then towed them by fishing boat to their new communities. This process of centralization, or “resettlement” as it was called, ultimately led to the displacement of nearly thirty thousand people. More than three hundred communities, many with histories stretching back centuries, would die a rapid death.

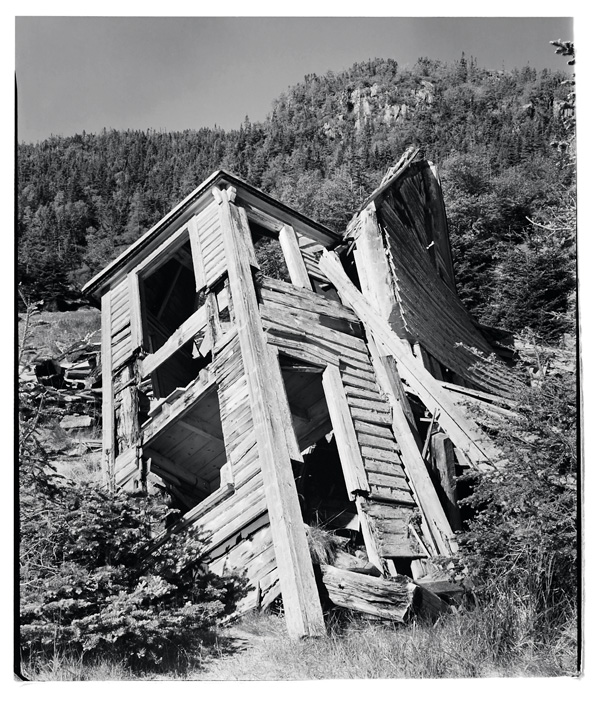

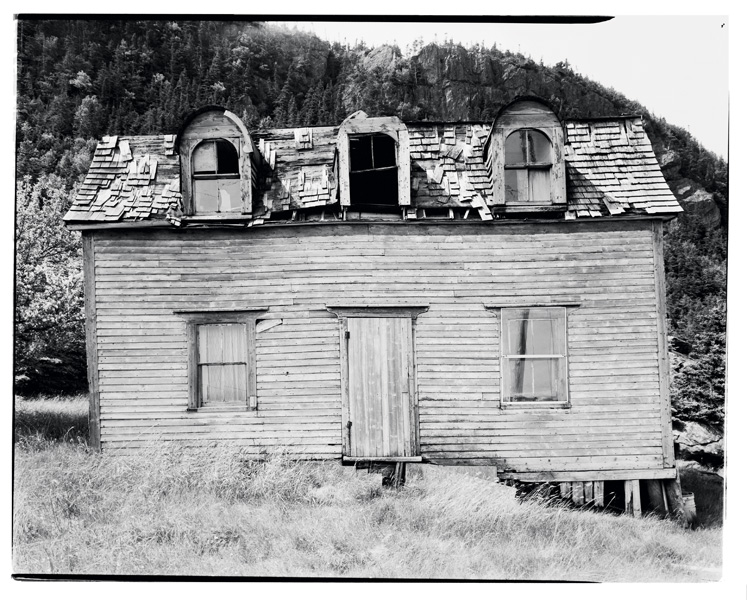

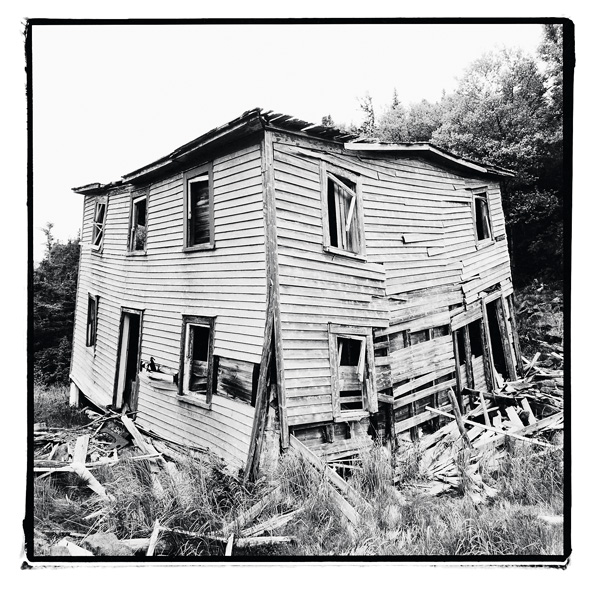

Not everything was floated to a new home. Churches, cemeteries, schools, docks, wharves, gardens, and many large houses had to be left behind. What remains is a Newfoundland coastline dotted with ghost towns. These aren’t ghost towns in the style of the American West, erected arbitrarily in the middle of vast arid plains. These communities had been built in places that called out for human habitation. They were tucked into sheltered coves where freshwater streams meet saltwater ocean, where the surrounding hills offered garden plots and clear boundaries for how big the community could grow. These towns were built in three dimensions, growing upward from the harbour to homes, churches, gardens, fruit trees, and cemeteries. They were nestled into the geography, not plunked down on it like houses on a Monopoly board. It is the human scale of these resettled communities, with their rich but ultimately tragic histories, that led me to spend a summer photographing their remnants.

Most resettled communities are no longer marked on maps. Once the inhabitants moved out, the community’s name was typically erased from official government publications, which helped keep the communities from sliding back into existence. This meant that I had to do some sleuthing in order to work up a list of places to visit and photograph. Investigations usually began in St. John’s, where I made a point of mentioning the project to people I met.

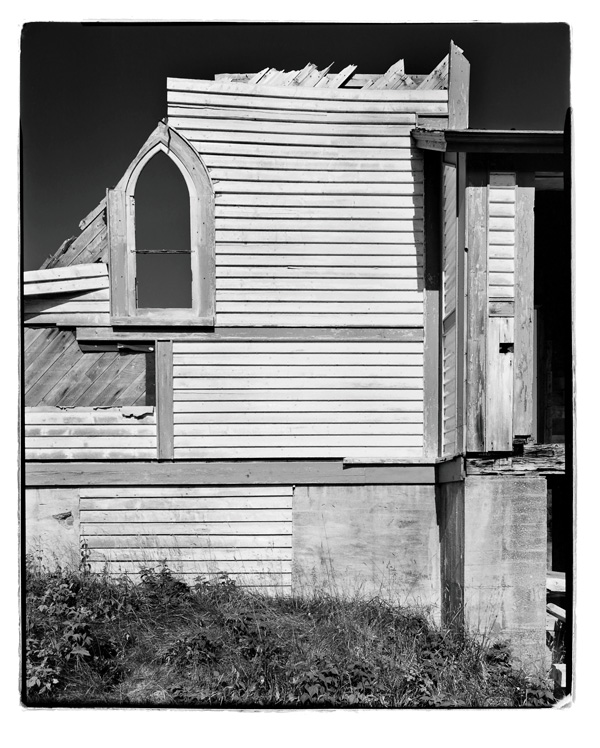

Several people suggested that I begin by photographing the church spire in the former community of Great Paradise, Placentia Bay. Paradise, I learned, had a history spanning more than two centuries, beginning at least as far back as 1758, and ending abruptly in 1967, when the town was abandoned as a result of the resettlement programs. In the early twentieth century, the community had a population of 197, a lobster-canning factory, a cooper, a church, a school, and the usual array of homes and wharfs. But by the spring of 1998, all that remained were a few headstones in the cemetery and the church spire, standing alone amidst the concrete foundations. Many people claimed that this spire was the most visually striking testament to resettlement anywhere in Newfoundland. Visible for miles out to sea, it was used as a point of navigation, its red-painted copper sheathing glowing in the sunlight over the treeless hills. Anticipating a signature image for the photographic series, I set out from St. John’s in search of this remote corner of Placentia Bay.

The first stop was Marystown for an evening of hospitality courtesy of Jack Brown, a teacher I’d met back in the summer of 1988. The conversation centred on resettlement. Jack had first-hand knowledge, as he had been raised on Bar Haven, a Placentia Bay island abandoned in 1966. He acknowledged that the isolation of the outport communities could make it more difficult for youths to get an education. But, isolated though they were, the communities on Bar Haven had significant histories and substantial infrastructure. Founded in the early nineteenth century or before, they had prospered in the early twentieth century. The largest community on the island had not only an elementary school, but also one of the largest churches in Placentia Bay. Jack questioned the wisdom of a government program that would lead to the demise of these communities within a single year. Such abrupt endings were especially difficult for elderly residents who, at a late stage in life, had to adjust to a new community and a very different lifestyle.

St. Leonard’s recorded history reaches back to 1803. Originally called Oliver’s Cove, it was renamed around 1876 by Father Doutney, the local priest, reportedly because the name’s association with notable Protestant Oliver Cromwell rankled the uniformly Catholic residents. Geographically, the community was built on the slopes of a valley that runs perpendicular to the shore. In the valley, a stream empties water from an inland pond into the ocean. The slopes were relatively fertile and supported several small farms; this combination of farming and the fishery gradually drew people to the area. The population peaked at 101 in 1857. A road was built to connect St. Leonard’s with the smaller but fast-growing community of St. Kyran’s, about three kilometres away on the other side of the isthmus. The road was later dubbed the Blue Road because of the tint of the local granite used in its construction.

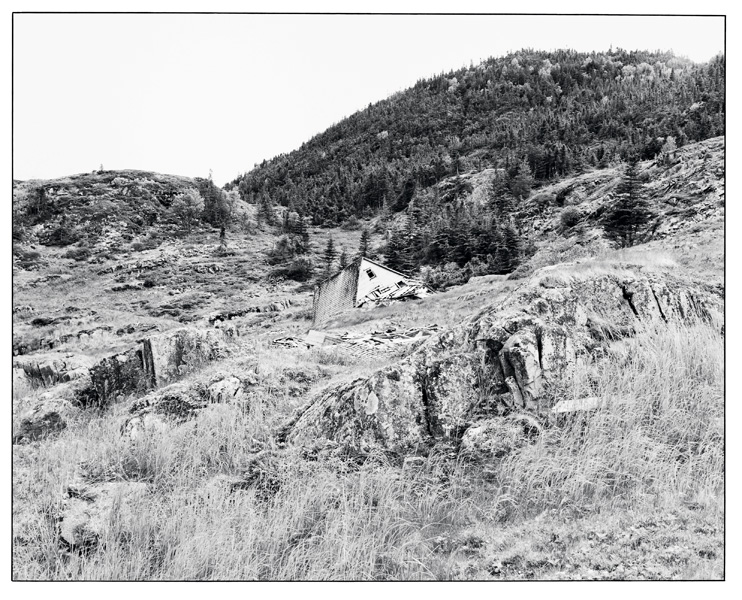

As I stood on the shore in 1998, however, not much remained. The grassy slopes of the valley were barren except for sinewy traces of roadbeds leading to the shore. The only relics of habitation were black holes that marked the entrances to root cellars, scattered piles of weather-bleached boards, and a single saltbox house, listing severely to port.

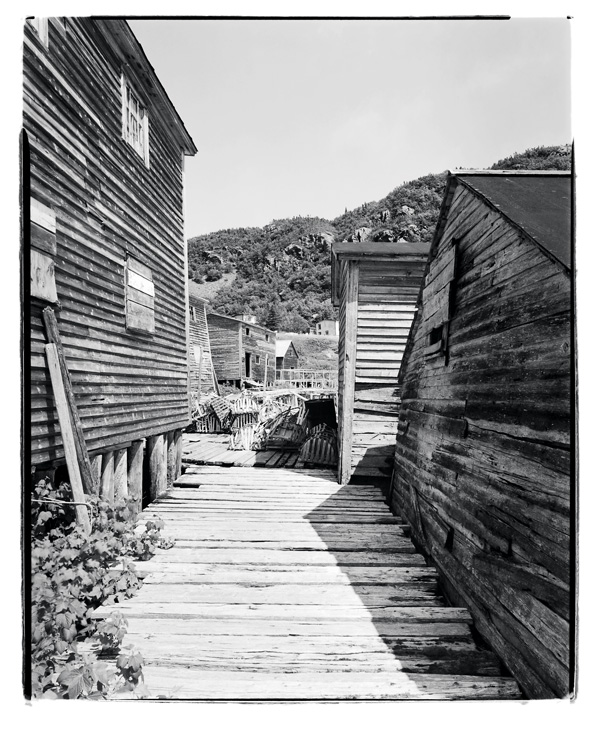

We travelled out of Snook’s Arm onto the open ocean, headed west, cut across the mouth of Wild Bight, and then, as we rounded Mouse Point, there was Indian Burying Place, exactly as described. At the end of the wharf was a well-preserved building with doors that slid open. Inside was a collection of nets and barrels and a badly worn table with a V-shaped notch cut in one side. Through a hole in the floor I could see the waters of the harbour a few metres below. Behind the building was a boardwalk, made of solid planks, that threaded between a number of storage sheds and then led to solid ground in one direction, and in the other, to a much less substantial platform made of thin, sun-bleached spruce trunks. I later learned that the building with the worn table was called the stage; the table inside was known as a splitting table, the storage sheds were also called stages, and the large platform made of spruce was known as a flake. All of these had been as much a part of the traditional salt fishery as the boats themselves.

Photographers, so often, are outsiders. Paul Strand was born and raised in New York and yet he photographed New England, the Gaspé, Italy, and France. Walker Evans was an upper-middle-class boy from St. Louis and Chicago, but he is most famous for photographing destitute sharecroppers in the Depression-era South. Born and raised in Switzerland, Robert Frank found himself criss-crossing ’50s-era America in an old Ford sedan, photographing its gas stations and diners with his Leica. Diane Arbus was of wealthy Fifth Avenue merchant stock, but she turned toward the margins of society, using her Rolleiflex to make portraits of circus performers, transvestites, and residents of homes for people with intellectual disabilities.

Like these heroes of mine, I have no interest in photographing what is familiar to me, such as the suburb of Toronto where I was raised. This is not because I doubt there’s anything worth photographing there; in fact, I’m confident that there is. Instead, I find myself drawn to things far from where I grew up: the crumbling factories of an early twentieth-century industrial park in Queens, New York; the discarded car seats and hot-water tanks dotting the New Jersey Meadowlands; and the remnants of Newfoundland’s resettled communities.

Excerpts from Scott Walden, Places Lost: In Search of Newfoundland’s Resettled Communities (Toronto: Lynx Images, 2003). The series Unsettled was shown at the Cambridge Galleries (Cambridge, Ontario), in July and August 2003. The exhibition was originally curated in 2001 by Bruce Johnston, for the Art Gallery of Newfoundland and Labrador, which organized and circulated the exhibition, accompanied by a small catalogue.

Born in 1961, raised in Toronto, Scott Walden moved to New York in 1988 to study philosophy at the City University of New York, receiving a Ph.D. in 1994. He teaches philosophy and photographic theory at New York University, and has published reviews and essays in C Magazine, Newfoundland Quarterly, and The Southern Journal of Philosophy. His photographs have been exhibited in Canada and the United States.