[Winter 2003]

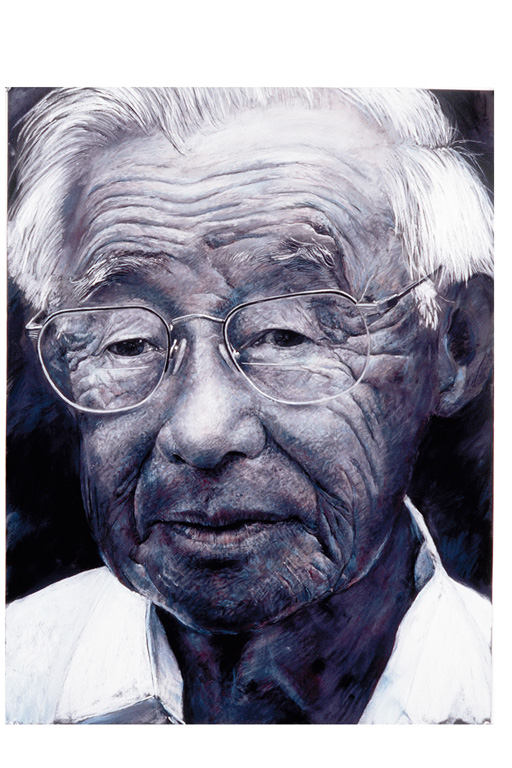

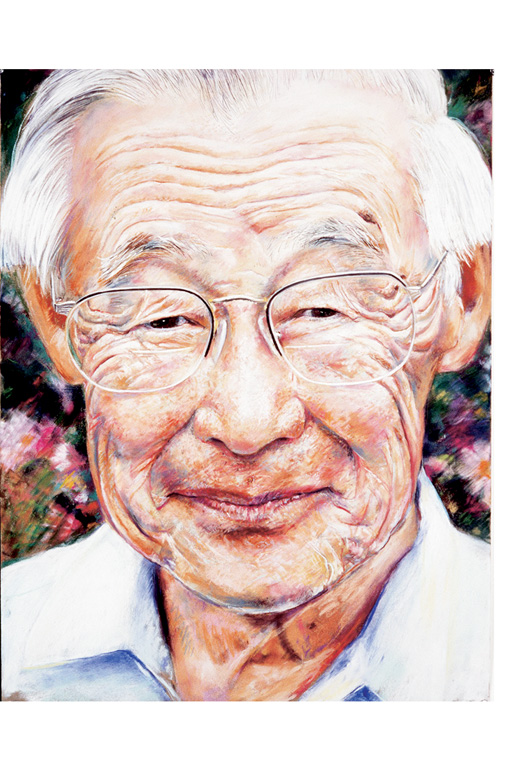

No longer simply an accurate depiction of physical characteristics or a “speaking likeness,” or a representation of the innermost personality of the sitter, a contemporary portrait can offer (for instance) a depiction of the individual’s relationship to his or her social or political environment, a study of the boundaries between the specific and the archetypal, or an inquiry into the delicate balance between theatricality and intimacy.

by Karen Love

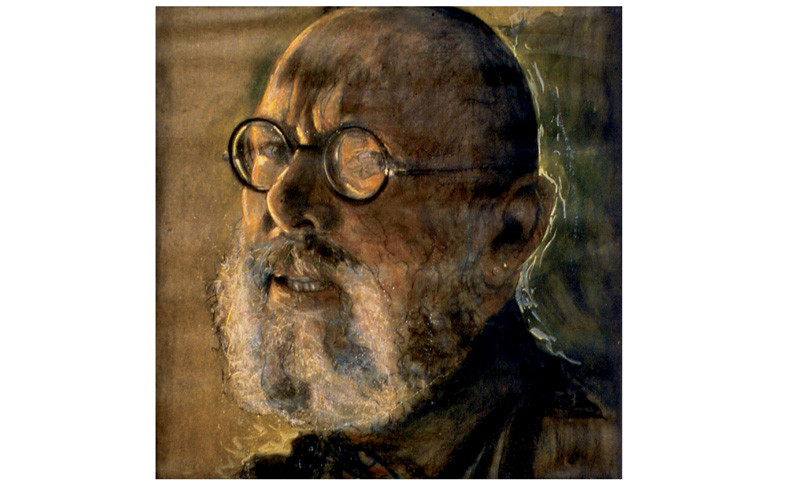

Artists have portrayed themselves and their fellows since the beginnings of human representation. The advent of the camera in the nineteenth century augmented portraiture’s accessibility with enormous rapidity and variation, both for those who wished to be portrayed and for those who were impelled to depict.

Twentieth-century life – in particular the latter fifty-year period with its dramatic high-tech transformations and postmodern attitudes toward how we understand the world – has drastically changed the ways in which we make and interpret a portrait.

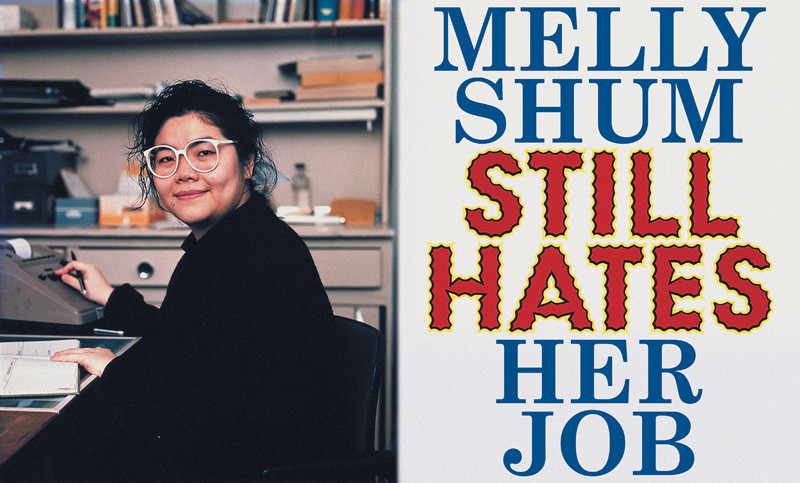

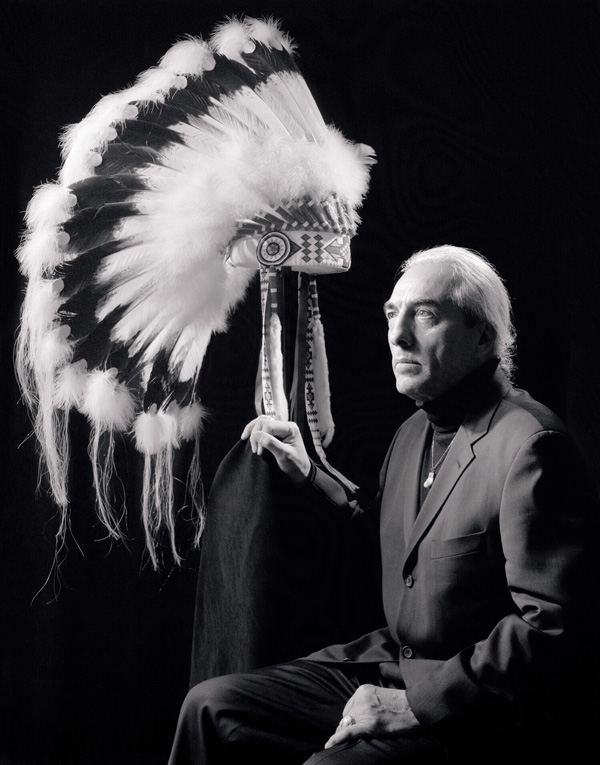

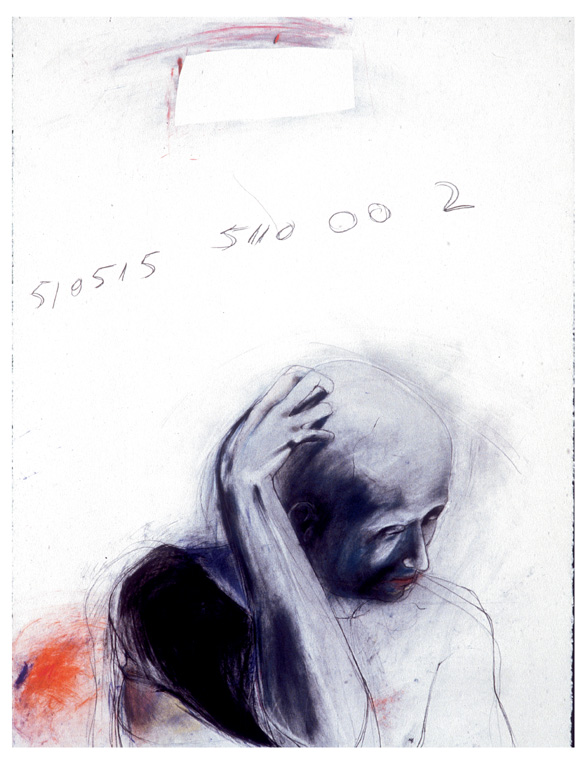

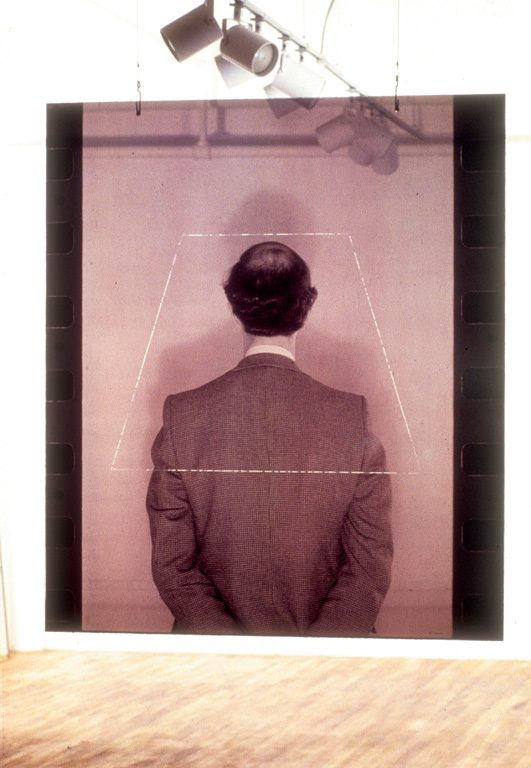

The representation of a human being is complex, both for the artist and for the receiver of the artist’s work. The image-maker may intend an accurate depiction of physical characteristics or may seek the innermost personality of the sitter. The illusion of a “speaking likeness,” that which encourages a sense of communication between the viewer and the subject, is still often sought after. Artists may also utilize the portrait genre to say something about the individual’s relationship to his or her social or political environment; to study the boundaries between the specific and the archetypal (for instance, as an exploration of human emotion); or to determine the delicate balance between theatricality and intimacy. Some work questions the ability of a portrait to uncover anything at all that is relevant or “real” about the evolving and pliable nature of identity.

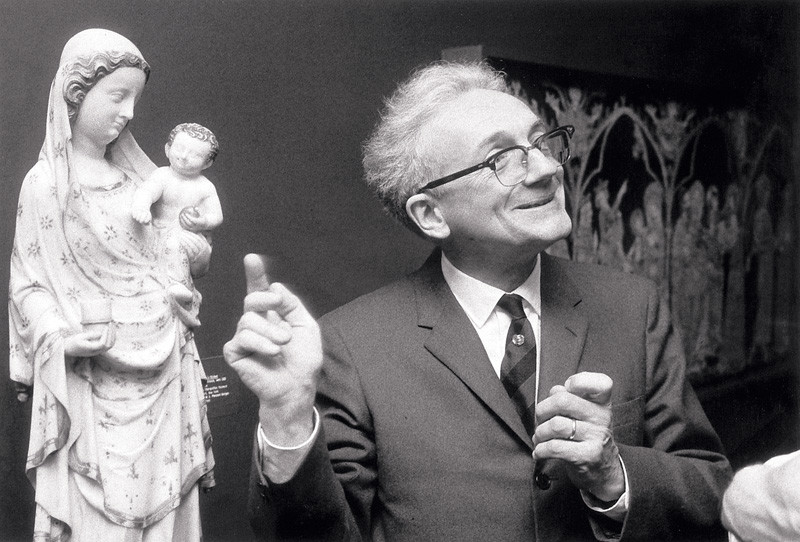

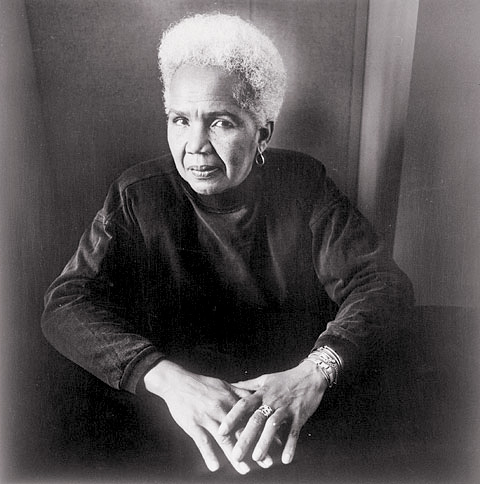

The Bigger Picture: Portraits from Ottawa was organized for the Ottawa Art Gallery’s fifteenth anniversary. This gathering of over two hundred Ottawa portraits by seventy-eight image-makers was intended to support the notion of accommodation of difference and encourage a heightened curiosity about the human condition. Not a formal history of the genre or the city, the show was organized thematically in order to offer comparisons between works from different decades (1950s to the present) and to present a myriad of questions about how we understand the idea of a portrait. The usual linear, chronological format stood aside for a play of juxtaposition, emphasizing instead parallels in content.

Larissa Fassler and Barbara Prokop’s colour photography series A Dinner Party for Sarah Smith presents bold, full-frontal colour portraits. All eight individuals, each of whom answer to the name of Sarah Smith and who range in age from a few months to perhaps thirty-five, responded to the artists’ invitation to attend a dinner in their honour. “Sarah Smith,” it turns out, is the most commonly used female name in Ottawa. In an innovative and witty manner the artists create a dialogue about community and the notion of an unconventional and temporal “family.”

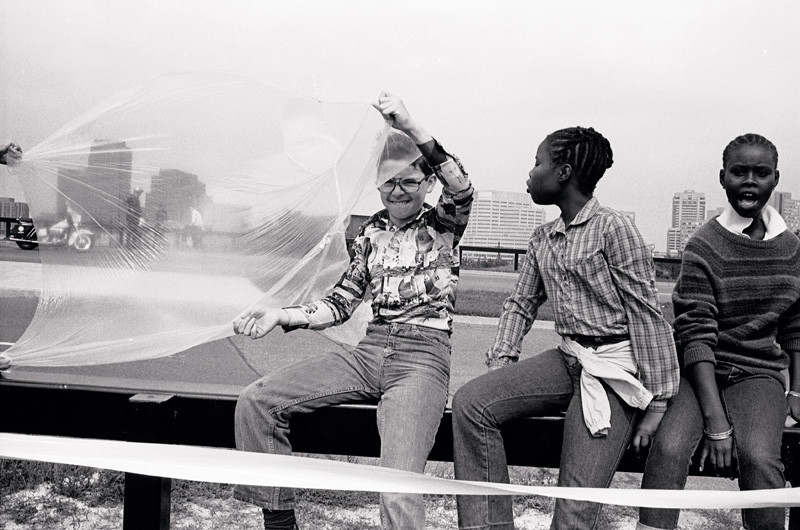

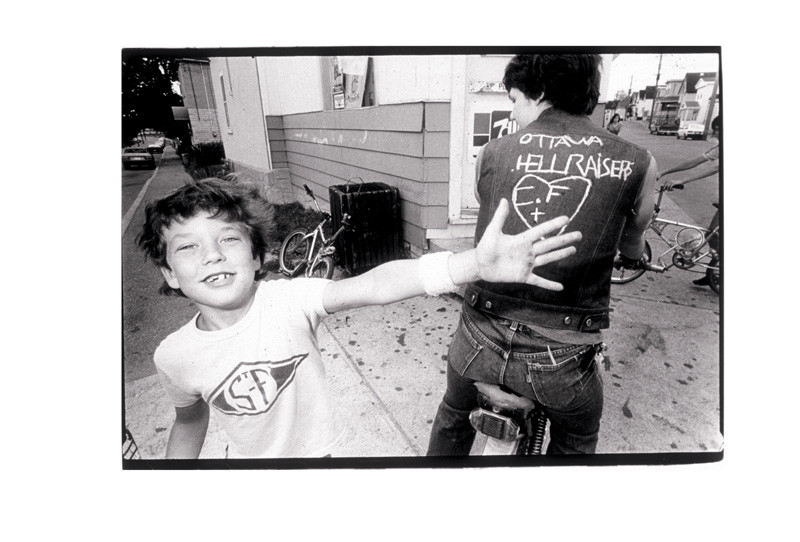

Illuminating both the local and the national identities of Ottawa, The Bigger Picture addresses ideas and representations about family, youth and community, touching on the nature/culture debate, the painful business of “becoming,” and the construction of identity; art and life and the intersection between the two; the street and public life, including the development of political consciousness and activism; work and play – how they can be intertwined and even reversed; and finally, the self: body and mind.

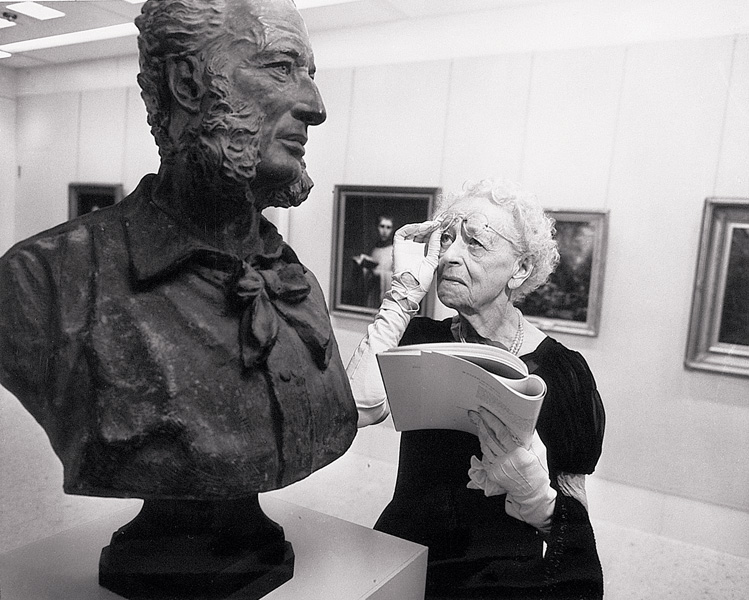

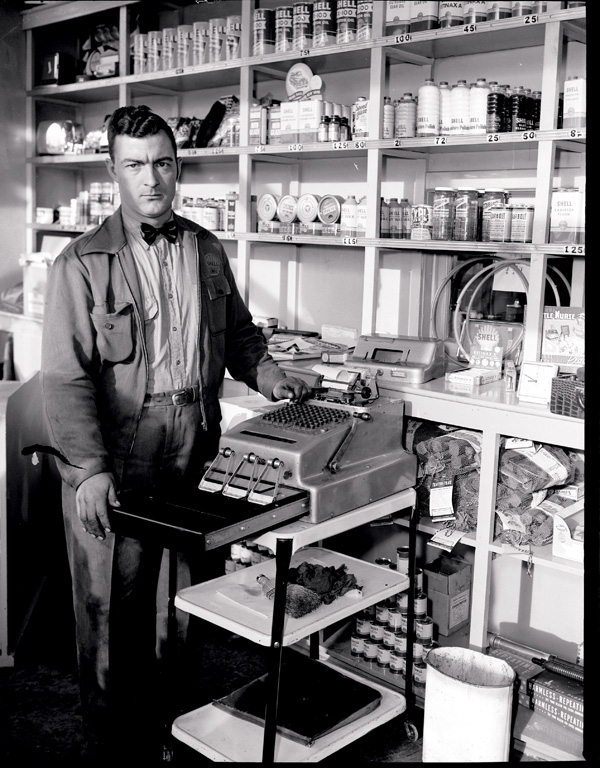

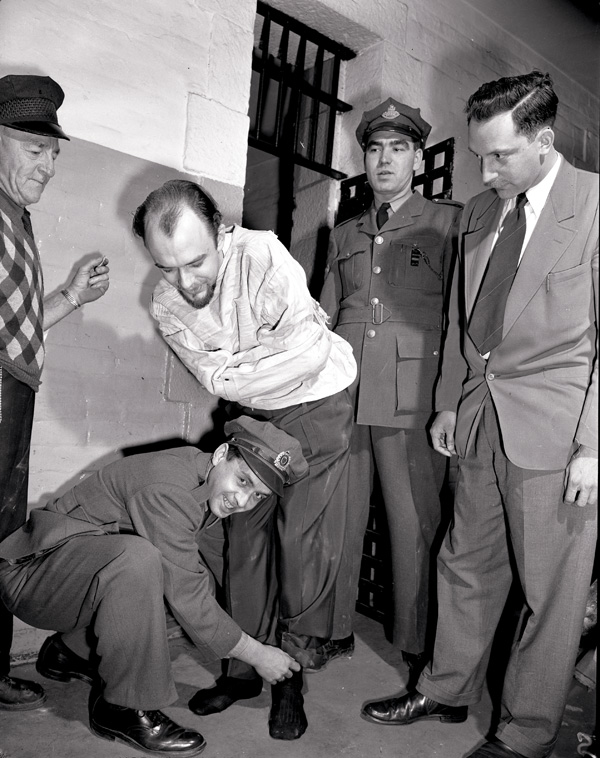

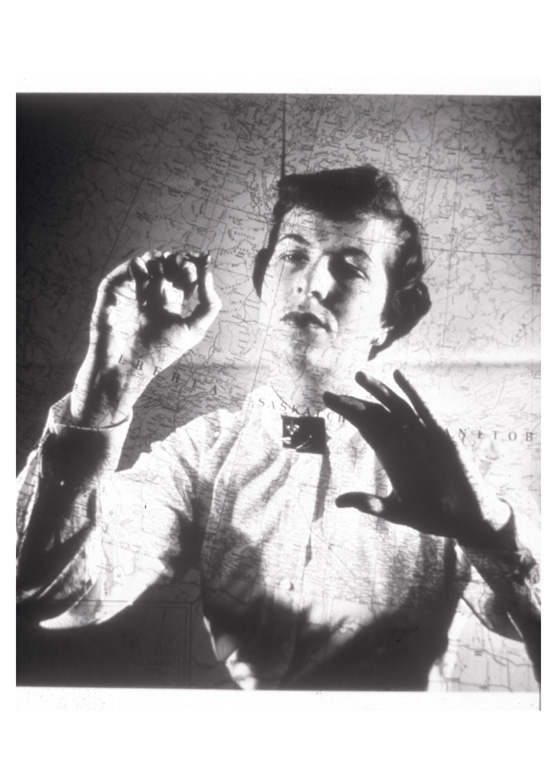

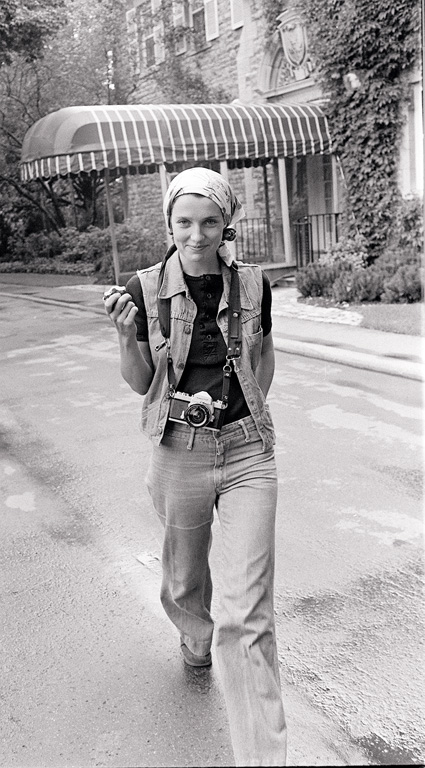

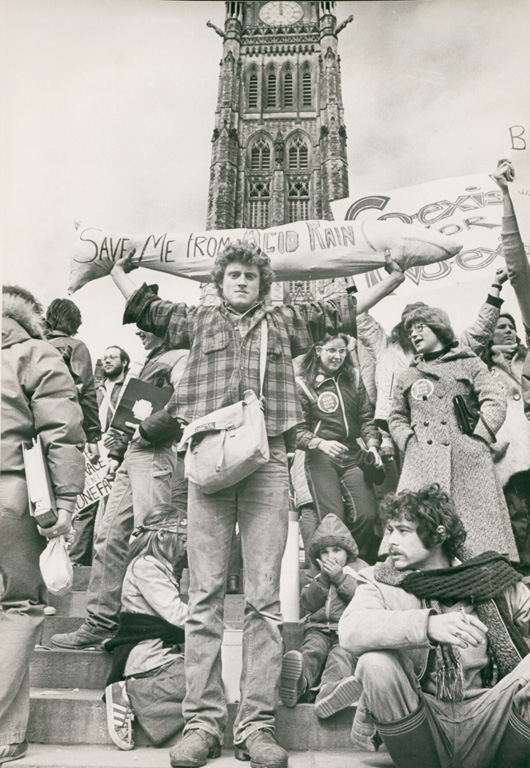

Portraits can accentuate our connections to the not-too-distant past: to those, among the many persons depicted in the project, who strove for an active family life or a dry place to sleep; who took pride in their work at the café, the Laundromat, or the embassy; who mastered a new bicycle or a destructive fire; or who aspired to a world without war or acid rain or cultural discrimination. The archival images in the show came from a wide range of sources: prints and negatives from commercial studios, Ottawa news media, and national image banks – many of which are now housed in national and municipal archives. These repositories generally hold an astonishingly large number of images, hundreds of thousands of visual stories that help to constitute our cultural histories.

A particularly broad-reaching, informative source is the Andrews/Newton Collection of negatives at the City of Ottawa Archives. Over 200,000 negatives from the 1940s to the 1990s were produced by a commercial photographic operation run principally by Andy Andrews and Bill Newton. These photos of (to us) strangers from former decades seem remarkably compelling. Many are so present and relevant in their style and candour, and put forward for recognition a recurring condition of human grace.

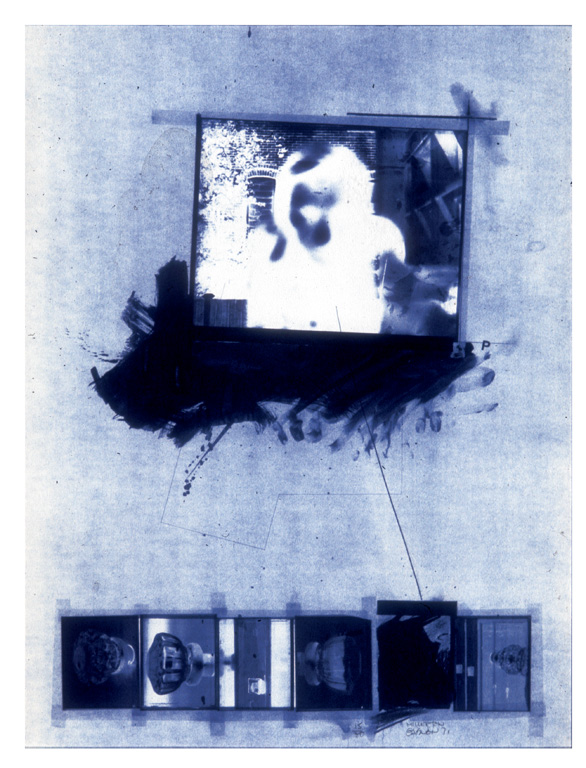

Max Dean’s electronic work, So, This is it, offers perhaps the perfect metaphor for the transitory nature of the human condition. It is about the viewer, very directly, and about the community in which it is presented no matter where the exhibition happens to take place. As you walk up to the wall-mounted piece, which functions continuously as a clock, the sound and movement sensors pick up your presence and instruct the video camera to take a black and white video grab of your face – suddenly you see yourself on the screen. But the hands of the clock are still working and the second hand begins to drag a white space as it moves forward. In sixty seconds you are gone.

The Bigger Picture: Portraits from Ottawa, organized for the Ottawa Art Gallery by Karen Love, runs from September 4, 2003 to January 4, 2004. This text is an extended version of the one published in the brochure accompanying the exhibition.

Karen Love is a Vancouver independent curator and editor who was the director/curator of Presentation House Gallery in Vancouver from 1983 to 2001. Her exhibition Facing History: Portraits from Vancouver (Presentation House Gallery) will be presented at the Canadian Cultural Centre in Paris for the summer of 2004. Love is currently developing projects on visionary landscapes (with Karen Henry), and contemporary art and the weather.