[Summer 2007]

Parisian Laundry, Montréal

January 12 – February 24, 2007

This welcome, timely, and provocative exhibition of photographic works by Lynne Cohen and Denis Farley shed considerable light on their respective oeuvres in a truly dialogical fashion. Lynne Cohen’s photographs have never looked more seductive and unsettling than they do in the present exhibition. Cohen’s own history is pristine: she began her career in the early 1970s with black-and-white photographs of interior spaces that demonstrate remarkable thematic continuity with her recent colour work. Her corpus is notable for its cohesive, coherent, and chilly scenes of institutional elegance. Her subjects include laboratories, offices, men’s clubs, and so forth – but with a deeply quiet and often menacing edge, as though she were shooting interior sequences for David Lynch’s Twin Peaks tv series or Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Her photography is all about the mystery of choice, and the magical places that her choices seize upon for us, her viewers, are seldom reassuring. We arrive at the threshold of her images willing to suspend our disbelief. But there is no doctoring, no staging, no fictional drama that might speak of an imagination in overdrive. Instead, we confront real places that seem like curious, unfamiliar non-places. And we are waylaid therein. These anonymous spaces are her dramatis personae. They are real, not imagined, and their occupants are always missing, as though some totalizing nuclear event has erased humans and left only their curious inhabitations unscathed.

These people-less places remind us of the non-places that the French anthropologist and theorist Marc Augé developed in his brilliant book Non-Places: Introduction to an Anthropology of Supermodernity. But while human agents are conspicuous by their absence in these photo-graphs, their work and leisure activities are often suggested as being consummately bizarre or hauntingly enigmatic. At least, their non-places – the strange rooms, offices, and labs – remind us of territories occupied by the dubious protagonists of British novelist J. G. Ballard’s disquieting fictions, even if the protagonists themselves are nowhere to be seen.

There is a stark clarity in Cohen’s images that seamlessly weds her choices of subject matter with their pristine, clinical presentation. She would be a Lucian Freud of the photographic image, if Freud the brilliant morgue pathologist/painter painted only place, not the human figure. The presentation is spare, stark, unrelenting in formal severity – and hypnotic – yet overwhelmingly sumptuous in its implications for non-places that the Other really does play and work within. Cohen induces a gradual about-face perspective and self-interrogation the longer we spend with her work. We question the identity of her non-places, and then our own identities when projected within them.

Even the framing decisions here seem absolutely radiant in their rightness. To encase her work appropriately, she frames her photographs in cast Formica, a layered plastic that shows no seams or distracting incidents of facture, highly complementary with many characteristics of the photograph’s multiple personae. If, in the 1980s, Cohen’s emphasis changed, it was only for wider emphasis, and greater particularity. She pursued institutional interiors that were enigmatic but further leavened with a healthy and eviscerating wit. These training centres, classrooms, and firing ranges possess a certain malevolence rather than charm. They have an edge that plays upon our own fears when it comes to severely regulated environments, whether biohazard lab or West Point military enclave. As her signature style continued to evolve, Cohen notched particularity a little higher on her aesthetic yardstick. In the 1990s, she looked to factories and other specific internal environments that suited her needs. Her recent use of colour demonstrates just how far she has come, for it effortlessly enhances, rather than compromises, the ground rules and governing aesthetic of her oeuvre. Colour pushes the sheer alien character of her locations still further into the foreground of our careful assimilation.

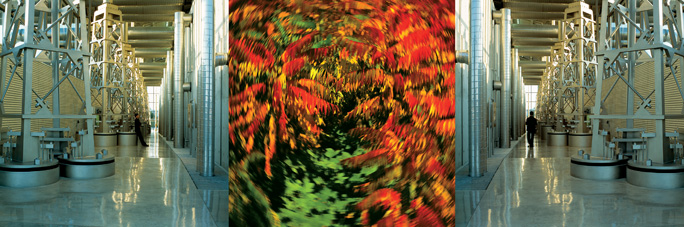

In Denis Farley’s work, we have a relatable, wholly maverick vision. One is tempted to suggest that his work is more romantic and subjectively utopian than Cohen’s clinical ideal. His images combining nature and architecture seem at first more human, more knowable, than Cohen’s sterile environments. Usually composed of several juxtaposed photographs, Farley’s works are radically over-determined, auratically speaking, in contrast with Cohen’s.

In his Displacement series, photographic panels portraying nature are interposed between other panels and suggest a giddy sense of vertigo, disruption. Presumably, Farley is attempting to convey the effect of the collision of place and non-place, the natural world and the built world, in the inner consciousness of a human subject – oftentimes, himself. As curator Jean-François Bélisle notes in his catalogue essay, “By containing nature in single panels and juxtaposing it with the built environment, he is encouraging viewers to compare the two. Similarities and contrasts emerge in terms of shapes and volumes between the different panels. However, what remains constant throughout the series is the absence of unconstrained nature in the built environment, and of constructions in the nature panels.”

In Farley’s Irradiations series of black-and-white photographs and video installation, he came closer to the non-place in its specificity. The photographer appears within the photographic space clothed in a curious red-and-white checkerboard outfit. In this costume, he photo-graphs himself in a true non-place – the so-called Diefenbunker. This structure was once a nuclear shelter for Canadian political leaders and support staff. The artificial light and sense of confinement bring back awkward memories of school drills in underground shelters during the Cold War, when the fear of Russian missiles raining down from above was at its zenith. Farley’s work triggers nostalgia and frisson in exploiting the tensions between place and non-place, nature and culture.

What is strikingly missing – but it is no stray, happenstance lacuna – is any indication that any of Cohen’s or Farley’s territories are meaningfully occupied. As various critics have noted, there are no untidy remnants of human passage, no detritus left by inhabitation like mute ciphers of the human fact. Herein, only pushbutton order rules supreme. In his Irradiations forays, Farley inserts himself into a checkered biohazard suit as though to suggest that a given non-place is toxic and the idea is to remain uncontaminated by the site in question. Cohen’s empty places speak eloquently of absent presences, enigmatic Others who hide in plain sight (I mean, of course, inside her viewers’ consciousnesses). Here is the salutary opening for the binary critique of non-place and the tense of supermodernity inside their respective bodies of work.

The writings of Augé, former director of studies at the École des hautes etudes en sciences sociales in Paris and an important French anthropologist, are important for identifying the nomenclature of non-place. Augé brilliantly assesses the topological and psychological particularities of site, both local and exotic, which are at one and the same time everywhere and nowhere today. In his aforementioned (and seminal) book, he argues that supermodernity is a new tense that effectively generates non-places like locusts in the midst of a whirlwind as the natural environment falls away in the wake of brick, mortar, and stainless steel. The principal trope of supermodernity is excess, after all, and this new tense is created through the logic of sheer excess. Augé defines non-places as possessing no identity or identifiable history. Non-places are purely transient. He identifies three species of accelerated transformation. In terms of temporality, he specifies an “acceleration of history” that ineluctably brings on an overabundance of events. He identifies a surplus in the realm of space: “The excess of space is correlative with the shrinking of the planet,” which brings on spatial overabundance. Finally, he identifies a specific figure of excess as “the figure of the ego, the individual.” The photographic works of Cohen and Farley imply all three orders of transformation, and their consequences.

Álvaro de los Ángeles was, to my knowledge, the first critic to associate non-place with Cohen’s work when he wrote, “The photo-graphs by Lynne Cohen deal with the concept of No-place. The complementary and diverse array of meanings related to this and the generic title of ‘No Man’s Land’ closes a ring of references and clues that are ethnological in nature, if not anthropological.”

De los Ángeles continues: “Typically a no man’s land is a strip of ground between one border and another: the line between countries as in a scale map. For Cohen, however, it refers more to the absence of human presence in particular interiors. Her no man’s land makes reference to the no-use-by the no-presence-of spaces normally used and inhabited (if only during the time of a massage or shower or the time it takes to walk down a corridor), not to forget the lack of vigilance, in those interiors which are usually monitored and controlled.” interpretation, they actually seek it.

He is dead on target. But one might suggest, further, that it is the very tense of supermodernity itself – with all its excesses, all its constraints, all its acceleration – which we inhabit today that makes the works under consideration so topical and pressing in presentation and implication.

Denis Farley photographs individuals in non-places, so his work is more illustrative of the effect of non-places on human agents – the living interface, as it were – and in some works he juxtaposes the non-place with the natural landscape, as if to show through counterpoint the alienation of humans in the whirligig of the built world.

One might suggest, then, that both Cohen and Farley are documentary photographers of non-place. Call Cohen an ethnologist of the near and Farley an ethnologist of the far, if you will. Indeed, one might hazard that Cohen and Farley offer a dialogical critique that dovetails with Augé’s negative definition of the non-place: “If a place can be defined as relational, historical and concerned with identity, then a space which cannot be defined as relational, or historical, or concerned with identity will be a non-place.” In Cohen’s work, the sheer wealth of such non-places shows that supermodernity accelerates their proliferation just as Farley shows that the human being is always displaced by and at odds within them. Augé holds that the word “non-place,” for him “designates two complementary but distinct realities: spaces formed in relation to certain ends (transport, transit, commerce, leisure), and the relations that individuals have with these spaces.” Cohen documents the former and suggests the latter by extension; Farley documents the latter, and yet the former is his own creative Ground Zero.

If non-places exist in contradistinction to places, it is because they exist within the parentheses of a forced solitude. Non-places all flourish behind locked doors, in confined spaces accessible only to those who know their combinations, possess keys in the form of credit and id cards, and journey through them or work inside them. They speak, above all, to our solipsism. They ignite a fuse that leads to reciprocal estrangement from the self. In effect, they illustrate and induce genuine displacement. The palpable alienation that non-places induce in us, even as they continue to fascinate, comes back to haunt us as a result of these photographers’ timely and deft investigations.

Denis Farley’s work is the perfect complement and counterpoint to Lynne Cohen’s. Kudos to curator Bélisle for perceiving that the resulting dialogue would be a neatly dovetailed fit – and one as persuasive as it is subversive, instructive, and revealing.

James D. Campbell is a writer on art and an independent curator based in Montreal. He is the author of over a hundred books and catalogues on art and artists.