[Spring 2008]

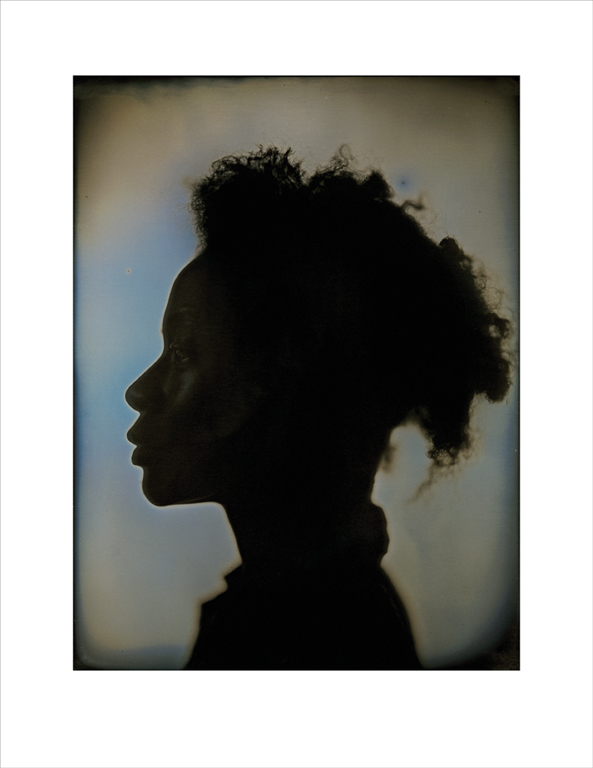

Following a first purchase, a work by Julia Margaret Cameron (United Kingdom, nineteenth century), the Lazare family has moulded the photographic content of it’s collection over the past twenty-five years to form what is a mainly contemporary ensemble of emotionally rich portraits and nostalgic landscapes. Whether it is a poetic photograph of the McIntyre ranch by Angela Grauerholz or a portrait in profile of Kara Walker by Chuck Close, the works in the Lazare family collection, spanning over a hundred years of photographic history, attest to a powerful sensibility and uncommon introspection.

by René Viau

With photographic portraits and landscapes, Jack Lazare, senior vice-president of Vision 2000, has made the walls of the travel agency group’s offices in downtown Montreal an expression of his tastes and sensibilities.

“This collection transforms our office – it makes it a more interesting space to live in,” Lazare says. Here, intuition and creativity are the last word, even people sometimes don’t agree with his choices. “I put what I want on the walls. If the people I work with don’t like some pieces, they certainly let me know. Many large companies that form collections use consultants and experts. If I had to consult with fifteen people, I’d never get anywhere. I can’t imagine delegating my choices.”

Although he doesn’t put it in these terms, it is obvious that Lazare, though discreet, has the courage of his conviction that art opens up possibilities and changes how we look at things. The works in his collection, never ordinary, testify in their way to the businessman’s flair. As some may remember, Lazare and his brother founded Gamma Records in the late 1960s; the company produced Robert Charlebois’s early records as well as many other artists, establishing the basis for a new Quebec music industry.

Cameron: Love at First Sight

Although he conducts detailed research on the artists whom he collects, Lazare’s motto could be the maxim of another collector, Georges Ortiz, who he likes to quote: “One can know too much and feel too little.” Lazare always notes that he keeps himself from intellectualizing his predilections and directions: “I react very spontaneously,” he says. He admits, however, that in many of the photographs that he has collected he appreciates the “content” and the “strength of the narrative dimension.”

An atmospheric landscape with uncertain horizons by Sugimoto sets the tone. “It gives an impression of incredible calm. At the same time, we are somewhere at the edge between what is real and what is abstract.” As in many of the other landscapes in his collection, the levels of readings are multiplied in this photograph. It is as if they were indicating that while they owe their physical and chemical existence to the undeniable indexes of what they portray, of what has been printed on their surface, they are also in the lineage of a body of knowledge inherited from painting. To one side is Edward Burtynsky’s panoramic view of an industrial site: a steel plant in China. In subtle colours, the composition aligns geometric lines and imposing pyramids of coal. Succeeding the raptures of the polite soft focus is a visual shock, again related to an art tradition: that of the sublime in English painting.

A lover of painting in the 1960s and 1970s, Lazare did not remain static, attached to his early taste for Käthe Kollwitz, Alex Katz, Jean-Paul Lemieux, and Christopher Pratt and his admiration for Lucian Freud, Giacometti, and Edward Hopper, of whom he owns several etchings and lithographs. In the mid-1980s, Brenda Lazare, one of his daughters, who lives in Toronto and is also a collector, introduced him to contemporary photography. He bought a Nan Goldin.

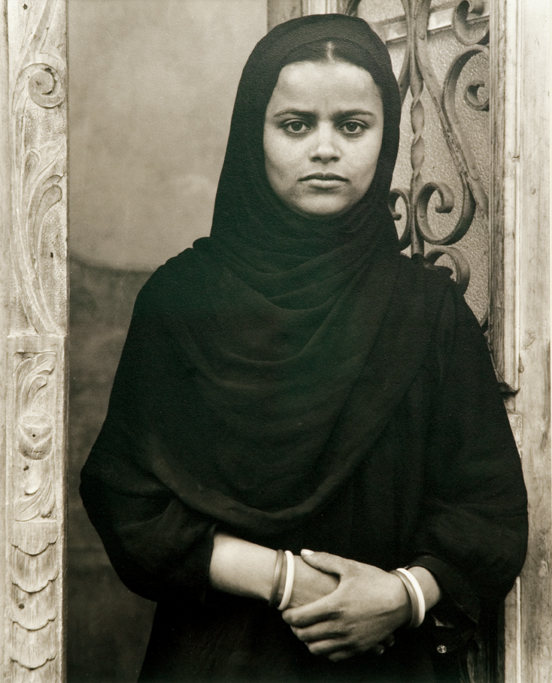

“At the beginning it was foreign to me, but I began to appreciate it.” He then fell in love with Julia Maria Cameron following a visit to a New York exhibition of works by this nineteenth-century photographer from the Isle of Wight. “I began to purchase Cameron’s photographs. And I’ve never stopped.” He owns more than ten of them. In these images from portfolios, the models’ faces are photographed in tight shots, a procedure that confers upon them a form of timelessness contradicted by a feeling of proximity and fascinating intimacy.

“Cameron’s photographs were a trigger. I was completely infatuated. In addition, they were within my price range at the time. She forced her models to sit and pose for her for hours. My predilection for realist painting also pushed me toward photography. Even though some of my photographs show a staged or altered realism, they are still realist.”

Since, he has made a method of becoming infatuated. “Starting with Cameron, I began to be interested in much more contemporary works. I read a great deal about Cameron. We visited the major collections that include her photographs. You know, it takes a great deal of work to build a collection intelligently, although I maintain that the emotional aspect is decisive.” Lazare admits that he makes many impulse purchases in London, Paris, and New York as well as Toronto and Montreal. “The decision is often made on the spur of the moment.”

Another axis of Lazare’s collection is represented by the self-portrait by Raymonde April. Featuring the elegant play of fabrics and the tracery of the clothing motifs, this portrait refers yet again to the perceptual dimensions of painting. “Raymonde April was a heavy influence. Montreal is generating exciting art. I love living here. I’ve lived here forever. And I’m happy that such a vital group of photographers lives and works here. I’m thinking of artists such as Angela Grauerholz, Pascal Grandmaison, and Nicolas Baier; there is also Isabelle Hayeur, who I don’t have in my collection.”

The guided tour continues. Nan Goldin’s photograph of a landscape is a departure from her gallery of offbeat characters from American society. Dark tones dominate a dramatic scene by brothers Carlos and Jason Sanchez. The protagonists are stuck in mud, victims of a catastrophe. Not far away, Burtynsky, represented also by a photograph of the dismantling of a ship in Bangladesh, has photographed a site in China to be evacuated for construction of the Yangzhou dam. “We are caught up in a sense of beauty that persists even though we know what will happen. In spite of imminent destruction, there is always life.” In A Motive for Change, Carlos and Jason Sanchez isolate a solitary traveller on the side of a forest road within an oppressive boreal landscape. Above is a photograph by John Szarkowski, ex-curator at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, taken in Minnesota, that testifies to Lazare’s interest in rural subjects. Once again, a road unfurls its imprint. Nearby, Larry Towell recalls, according to Lazare, the images of the economic crisis taken by Dorothea Lange, which made a great impression on him. And Mark Ruwedel, on a nearby wall, offers evocations of the American West and communicates a feeling of space and immensity. There is also a foggy landscape by Sally Mann.

A large-format portrait by Irish photographer Willie Doherty, Unspecified Threat, purchased in New York, is hanging behind the receptionist’s desk. In a halo of disturbing shadows, Doherty situates his subject at the edges of a certain suggested violence. Atypical within the series on aristocrats, a portrait by Patrick Faigenbaum traces the features of a young boy. Attention is drawn more to the psychological expression than to his attributes or the décor denoting a comfortable social class.

Portrait of the Portrait

When it comes to the choices for his house, Lazare makes his selections in concert with his wife, Harriet Lazare: Shimon Attie, Jose Manuel Ballister, Beate Gutschow, another Szarkowski, Paul Strand, Michal Rovner, Sarah Moon. The portraits, such as the paradoxical one of Kate Moss by Chuck Close, have a timeless aspect that distinguishes them from the intimate photographs that proliferated obsessively starting in the 1990s. Elsewhere, a composition by Teresa Hubbard and Alexander Birchler has an association, Lazare feels, with Hopper’s world.

In the couple’s dining room is a series of portraits by Julia Margaret Cameron recalling the Florentine madonnas that inspired her and, much later, movie maker Carl Dreyer. On the other side, above the chronologies, is a contemporary portrait by Montrealer Pascal Grandmaison. In contrast to the bold composition and sense of presence of Cameron’s faces is the melancholic distance that Grandmaison creates. At the core of Grandmaison’s composition, a plate of glass isolates the model, who seems absent to himself and to the viewer. The face is smoothed out, set apart, “fixed” under the glass as a specimen might be. Although it works in an opposite way to Cameron’s portraits, which magnifies her subject, Grandmaison’s portrait also transmits something quite different from appearance or the conveying of someone’s identity. From one artist to another, this form broadens and is transformed. Before us is, in a way, is a “portrait of the portrait.” An internal game is set up. When different approaches and ways of constructing the question are brought together, paths open up. The collection thus creates new configurations and openings. It tells us an endless story.

Several works from Jack Lazare’s collection are on display in the exhibition Pour l’art! Œuvres de nos grands collectionneurs privés at the Musée des beaux-arts de Montréal (December 6, 2007, to February 24, 2008).

Translated by Käthe Roth

Jack et Harriet Lazare began collecting representational painting in the 1960s. They became interested in photography after seeing the exhibition titled Julia Margaret Cameron’s Women at MOMA in 1999. They immediately began collecting Cameron’s work. Recently, their collection has broadened to include Canadian and international contemporary photography.

Cultural journalist and art critic René Viau has contributed to numerous publications in both Quebec and France. He has published a number of books on Quebec artists, and his first novel was released in 2006.