[Spring 2008]

by Maria-Antonella Pelizzari

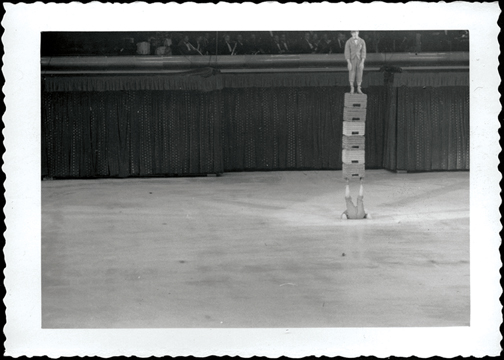

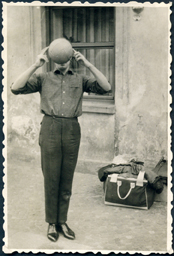

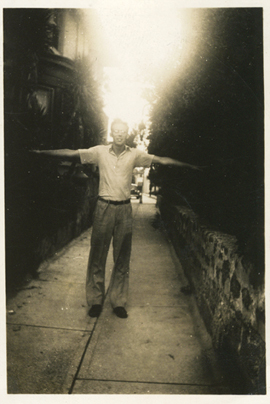

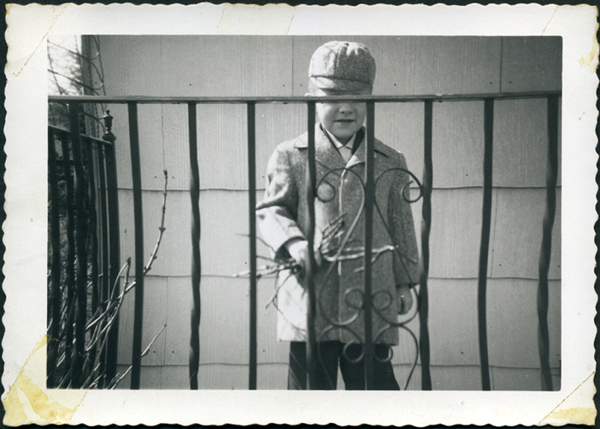

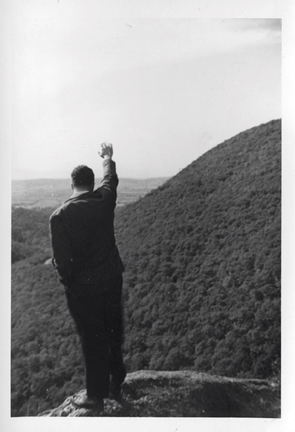

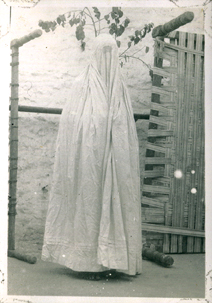

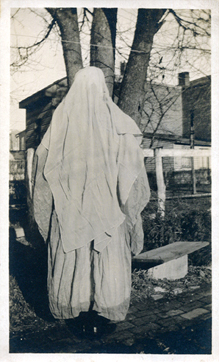

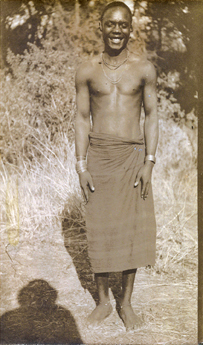

W. M. Hunt’s photograph collection Collection Dancing Bear whispers some secrets about photography. It is full of mystery, chaos, darkness, and excitement. It is unpredictable. It is creepy. It is provocative. It is playful, in its seemingly random selection of “magical and heart-stopping photographs of people whose eyes cannot be seen.”1 This unusual focus brings vernacular images gathered from flea markets together with works by well-known artists, reflecting multiple and contingent facets of one obsession: photography and the invisibility of the subject. About this enigma, W. M. Hunt says, “The collection, it is me… it is a chronicle of my own sense of self-esteem, a diary of my own legitimacy.”2 An ensemble of over one thousand images, put together in more than thirty years, the collection is a work of art in itself – free, unconditioned, and arbitrary. How does this work inspire a new (fresh, spontaneous) way of looking at photography, and what does it mean to collect these kinds of pictures?

W. M. Hunt calls for “legitimacy” for vernacular photography, transgressing any codified categorization of photography as “art.” The alternative exhibition formats that he has chosen for these photographs confirm his keen interest in photography as experience.3

At the Musée de l’Élysée in Lausanne, he showed a digital projection of five hundred snapshots, suggesting the temporal and sequential montages of photo albums. At FOAM, in Amsterdam, he wanted to reconstitute the tactile and intimate life of family snapshots, and so he allowed visitors to touch and cherish them as keepsakes. He had facsimiles made of his vernacular photographs by scanning and reprinting them, and then cutting these exact copies with deckle-edged scissors. Visitors could pick them up and take them home as souvenirs, in a democratic spirit similar to that in a Felix-Gonzales Torres installation, at which a heap of digital reproductions in a gallery setting is available to everybody.

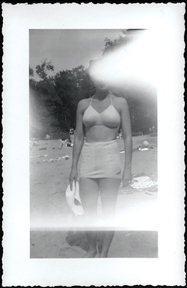

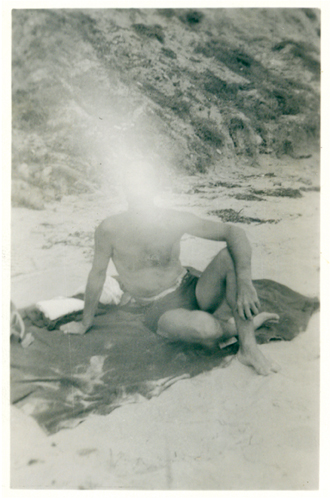

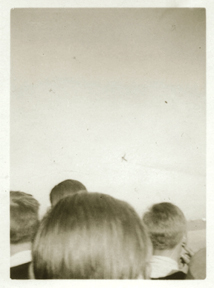

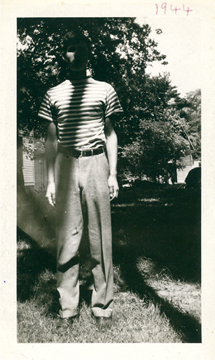

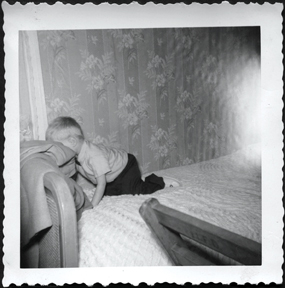

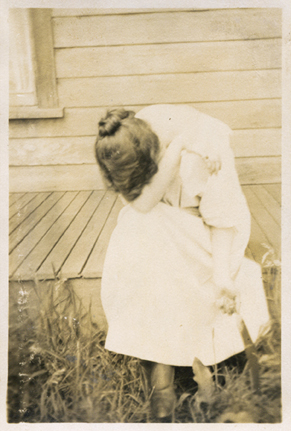

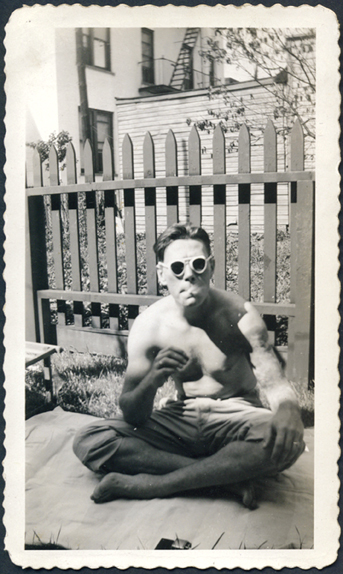

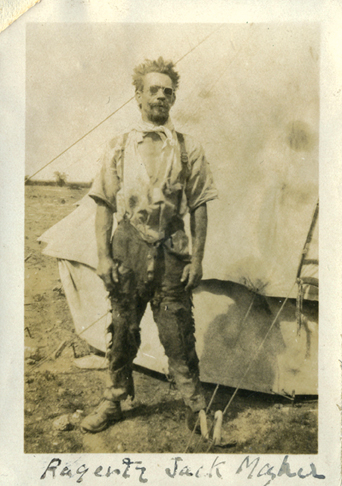

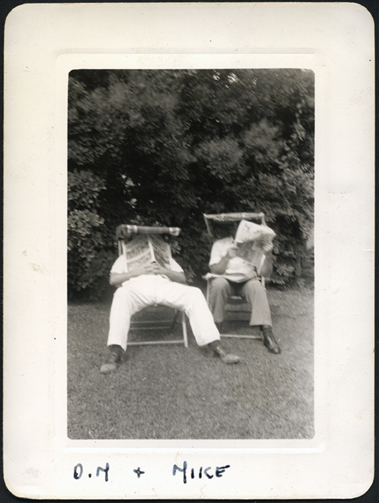

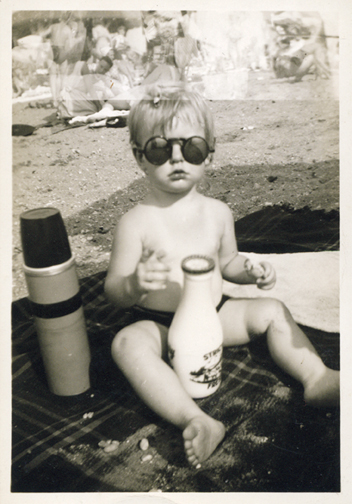

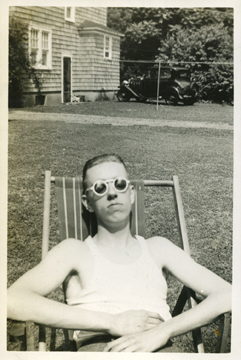

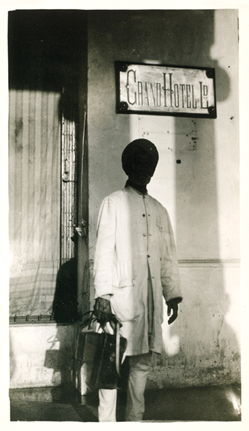

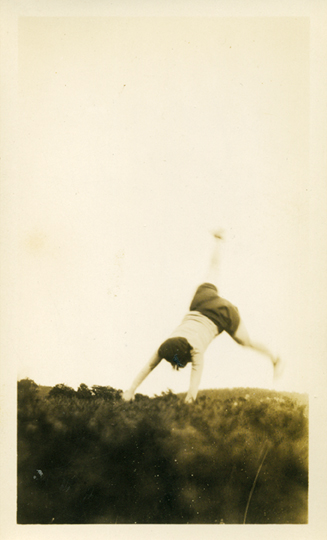

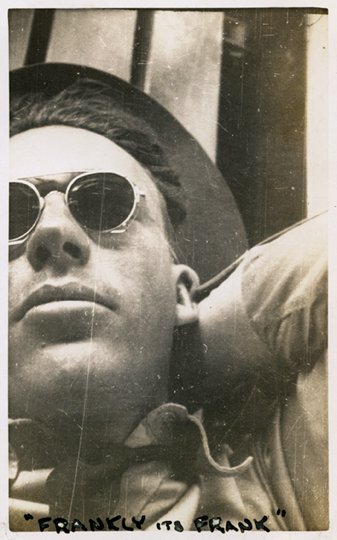

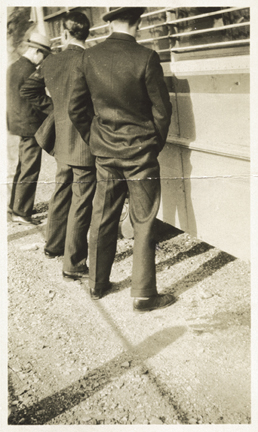

Hunt also arranged the original snapshots on red construction-paper pages under particular themes, creating typologies of pictures. For example, a portrait of “Frank” was no longer about “Frank,” but about a man wearing dark sunglasses; “Elise diving from our raft” was significant because Elise’s face was in the water, like many other headless bathers grouped in Elise’s file. And so on and so forth, with people sleeping, sunbathing, wearing masks, playing hide and seek, laughing, or consciously refusing to be photographed. Such a bizarre organization of personal photographic mementos into “species” of photographs likens Hunt’s project to Gerhard Richter’s heterogeneous Atlas and Joachim Schmidt’s Archiv.4 Like Richter and Schmidt, Hunt the artist/collector dismantles the uniqueness of personal snapshots into collective Kodak moments and mediated events, grouping them into taxonomies (flares of light, children, clowns, parties, etc.) that appear to be didactic studies and archival ordering systems. But the comparison stops here, at a formal level of organization. Defined by Hunt as “some obscure surrealist’s scrapbook,”5 this grid-like montage is extremely idiosyncratic and lays out the collector’s chaotic taste and visual memory. Even when presented as an orderly “archive,” Hunt’s vernacular collection defies order and habit, as it seeks shocks of the visual. As Benjamin observed of his own library, “What else is this collection but a disorder to which habit has accommodated itself to such an extent that it can appear as order?”6

It is quite telling for this short investigation into the world of a collector of invisible faces that Hunt started to gather these kinds of photographs while he was working as an actor. It is also revelatory that he became involved in the world of photography while working at the Ricco/Maresca Gallery – a gallery that focused, mainly, on vernacular art. In 1997, many of these preoccupations coalesced into Hunt’s whimsical show titled delirium, which presented a very unorthodox sequence of photographs dealing with extreme moments in life, from physical and psychological alienation to spiritual rapture to sexual fulfilment.7 Some pictures from his No Eyes collection were part of the selection, together with loans from galleries and friends. This unpredictable show was a lesson in the history of photography, an eye-opener, ranging from nineteenth-century pictures of the insane to Weegee’s shot of an exhausted alcoholic in the streets of New York. The photographs magically captured the human body undergoing a physical transformation.

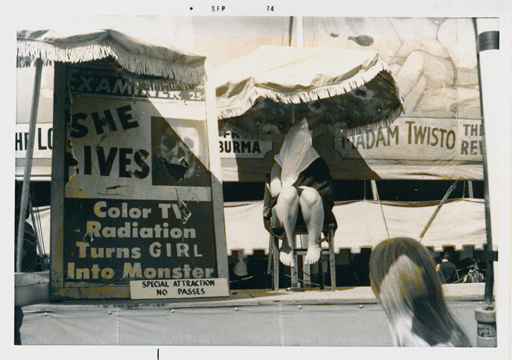

When I see photographs from the collection of people with “no eyes” laughing, closing their eyes in a grimace, and becoming blurred ghosts, the message of “delirium” makes perfect sense. In both cases, photography is a vehicle to the unknown, and the unknown is represented with trepidation and humour. Take, for example, one of Hunt’s favourites: an amateur photograph taken by Maureen Anderman at the Minnesota State Fair sometime in the 1970s. Hunt calls it his “Garry Winogrand.”8 It consists of a dynamic encounter between a blonde woman, passing by, and the fair’s attraction – a half-naked woman sitting on a chair, her face covered with a light veil, waiting to be revealed as the girl-turned-into-monster due to the effects of radiation from a colour television set. The passerby suggests the experience of looking through the lens – voyeurism, curiosity, and the silent communication between the photographer and the passive object in the viewfinder. The veiled woman signals the fragility of being exposed and becoming a disfigured face, a monster, and a ghostly presence.

Looking at this photograph and many others in the collection, one inevitably thinks of Barthes’s Camera Lucida, in which the author describes his discomfort with and inner resistance to the camera: “Each time I am (or let myself be) photographed, I invariably suffer from a sensation of inauthenticity, sometimes of imposture (comparable to certain nightmares)… the Photograph… represents that very subtle moment when, to tell the truth, I am neither subject nor object but a subject who feels he is becoming an object: I then experience a micro-version of death… I am truly becoming a specter.”9 This struggle with his mechanical double inspired Barthes’s personal investigation into “the profound madness of Photography,”10 unravelling his own “delirium” in finding the “authentic” photograph of his lost mother. Once he found that image, he left it invisible to his readers.

In a similar way, the photographs in Hunt’s vernacular collection defy the possibility of capturing the “authentic” image of the self – they reflect the discomfort of individuals in front of the camera, resisting objectification by covering their eyes. If many of their gestures recall iconic pictures in the history of photography – by Dr. Hugh Diamond, Albert Londe, Oscar Gustav Rejlander, Julia Margaret Cameron, Diane Arbus, Imogen Cunningham, Ralph Eugene Meatyard, Duane Michals, Andre Kertesz, Lisette Model, Richard Avedon, Weegee, Brassai, Robert Frank, and Winogrand – this goes to prove that professional photographers have also investigated the enigma of the ghost, by staging or spontaneously capturing people’s fleeting expressions.

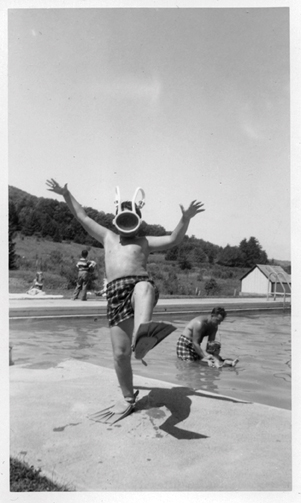

The flaws contained in snapshot mementos (i.e., subjects who are not centred, who are not looking directly into the camera, who seem disproportioned, who are photographed in action and performing sports) are oftentimes revealing of photography as the impossible art of stopping time and grasping someone’s secret. The sheer, simple pleasure of looking at these photographs without established hierarchies, but, rather, for their value as unique objects – cherished once when they were taken, later dispersed, and now made “legitimate” – is Hunt’s ultimate invitation, as he unravels who he is through his doubled and masked anonymous people.

1 Paul Gachot, “No Eyes, Many Feats. Conversations with W. M. Hunt: Collector, Curator, Dealer and Gallery Owner Extraordinaire.” http ://www.point-mag.com/pdf/Point-WilliamHunt.pdf.

2 W. M. Hunt, “Legitimacy and the Walls of the Dancing Bear Cave,” lecture given at the National Gallery of Art, Washington DC, November 10, 2007.

3 The collection was presented at the Rencontre d’Arles in summer 2005; at the Musée de l’Élysée in Lausanne, in spring 2006; and at FOAM in Amsterdam in spring 2007.

4 See Benjamin Buchloh, “Gerhard Richter’s ‘Atlas’: The Anomic Archive,” October 88 (Spring 1999), 117–45; Gordon MacDonald and John Weber (eds.), Joachim Schmid : Photoworks 1982–2007 (London :Steidl Publishing, 2007).

5 Hunt, “Legitimacy.”

6 Walter Benjamin, “Unpacking my Library. A Talk about Book Collecting (1931),” in Illuminations (New York : Schocken Books, 1968), p. 60.

7 See Aperture 148 (Summer 1997).

8 Hunt, “Legitimacy.”

9 Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography (New York : Hill and Wang, 1981), p. 13.

10 Ibid., p. 13.

W. M. Hunt – Bill Hunt – is an active collector, a curator, and a consultant in the New York art world. Responsible for photography at the Ricco/Maresca Gallery for many years, he later opened his own photography gallery with Sarah Hasted (Hasted Hunt, http://www.hastedhunt.com). Selected works from his private collection were exhibited at the 2006 Rencontres d’Arles and at the Musée de l’Elysée in Lausanne in 2007. A book about his collection will be published by Thames and Hudson in 2008.

Maria Antonella Pelizzari is an associate professor in the Department of Art at Hunter College, City Unversity of New York, where she teaches history of photography. She is the editor of the book Traces of India: Photography, Architecture, and the Politics of Representation, 1850-1900, and she is currently working on a new book on photography in Italy, which will be published by Reaktion Press.