[Spring 2008]

by John Bentley Mays

Archiving Contemporary Anxieties

Toronto collector Ydessa Hendeles is no ordinary gatherer of photographs. Instead of following the usual practice of connoisseurs – buying only rare images that show artists at the top of their technical game – she has always acquired images on the basis of their power to lay bare the urgent cultural themes that fascinate or trouble her.

These diagnostic pictures have been assembled and shown in sharply focused groups ranging in size from a handful of images (the startling Vietnam photographs of journalist Eddie Adams, for example) to thousands (the postcards, formal portraits, and snapshots of toy bear. The groups of images, in turn, have been exhibited with artworks and other cultural artefacts that investigate, as total ensembles, the topics that have intrigued Hendeles throughout the twenty-year history of Toronto’s Ydessa Hendeles Art Foundation: the seduction of power, the myths of America, the dangerous hankering for roots, and many others.

A good example of what I am talking about – and interesting evidence for the force with which Hendeles has swum against the recent tide of connoisseur photographic collecting – is the Teddy Bear Project, which was shown first in Toronto in 2001 and later, in a greatly expanded version, in Munich and Shawinigan.

This archival work of imagination and obsession was composed of thousands of vernacular photographs of teddies from the last century. Considered individually, a given picture held only limited, though real, sentimental or aesthetic interest. One showed a serious Edwardian girl, attired in frills and bows for the portrait artist, clutching her well-loved teddy. Another depicted a child’s tea-party for bears, yet another a mascot teddy sturdily posed among its football team or a platoon of soldiers – and so on, through a vast declension and variety of situations in which people and their toy teddies have been photographed.

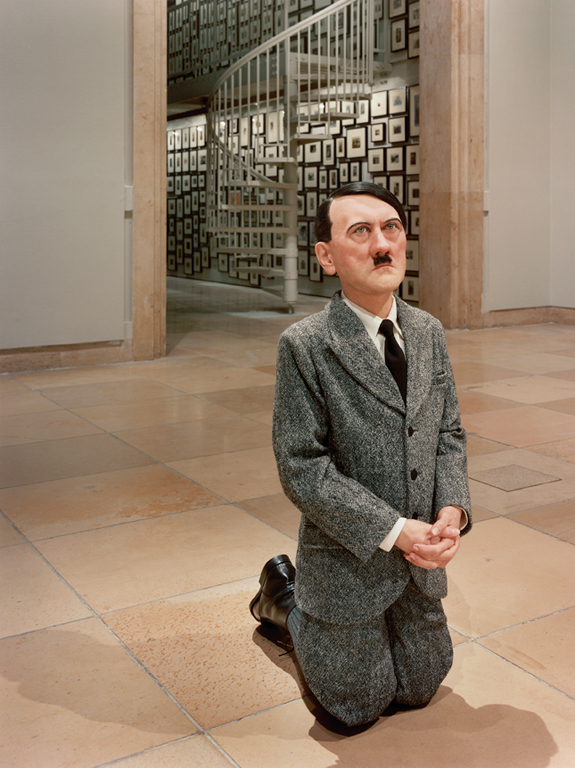

Having allowed us to enjoy the light pleasure offered by this dizzying panoply of pictures, however, Hendeles invites us into an adjoining gallery, in which the only object is Maurizio Cattelan’s sculpture Him. It is a boy-sized, kneeling statue of Hitler, his hands clasped in prayer, his tender blue eyes raised to the heavens. We are abruptly brought face to face with this monster of the twentieth century, not now the raving demagogue of contemporary newsreels and photojournalism, but the vulnerable, innocent, God-intoxicated ecstatic that millions of deluded Germans once believed him to be – their rescuer from alienation and disorder, their mascot: their teddy bear.

Suddenly, the Teddy Bear Project is no longer about the timeless joy of childhood – or at least not only that. It is also about the desperate illusion of safety and security that swept over whole nations in the last century, dragging them down into horror and degradation. The teddy-bear pictures lose none of their delight in this moment of transfiguration, but their charm becomes shadowed by existential dread. Seeing the pictures in the context provided by the Cattelan sculpture – a reminder of the real history of the era in which teddies enjoyed their greatest vogue – we realize that the Teddy Bear Project is less about toys than about the yearning of millions in the chaotic twentieth century for safety, comfort, and familiarity, and the doom that befell them when one or another of the competing totalitarianisms of the epoch obliged their desire.

Among the other families of photographs that Hendeles has assembled during the career of her foundation, several merit appreciation in their own right, as well as for their role as elements in larger exhibitions. These include a group of Bernd and Hilla Becher’s extraordinary Typologies, and gatherings of images by Walker Evans, Diane Arbus, Paul Strand and the obscure photographer of the New Orleans red-light district, E. J. Bellocq.

None of these artists, however, serve Hendeles’s cultural investigations more eloquently or more memorably than her works by photojournalists. In the 1995 foundation show called Chronicles, for instance, Hendeles combined images by Hanne Darboven and the date paintings of On Kawara with a sequence of eight photographs taken in Vietnam by Associated Press photographer Eddie Adams. The pictures by Adams included the most famous news photo of the Vietnam conflict: the 1968 image of the shooting of a Viet Cong insurgent by a South Vietnamese general. More forcefully than any other photograph of its era, Adams’s brutally frank image brought home to Americans the truth of the war, the reality that lay behind the abstractions used by the U.S. government to sell its war.

She has always acquired images on the basis of their power to lay bare the urgent cultural themes that fascinate or trouble her.

Or did it? Before deciding that Adams’s photograph is an example of photography’s truth-telling power, we would do well to remember the many unseen hands that mould and position the public reception of news pictures: assignment editors, darkroom staff, layout artists, and senior editors, the whole industrial-scale apparatus and technology of news creation. The graphic pictures by Adams ultimately prove nothing about photography, and less than nothing about the good intentions of news organizations. Emerging from a show of blunt facts (Kawara’s paintings of calendar dates) and the painful, half-hallucinatory recollections of Hanne Darboven, they raised crucial, complicated questions about truth in the age of information – provocative questions that lay at the heart of Hendeles’s Chronicles. Is the communication of truth – annunciatory, penetrating, life-giving – even possible in a culture of endless surprises, disgorged every instant by the machinery of mass media? Is Adams’s image of a Viet Cong solider getting his brains blown out really attractive not because of the truth it presumes to give us, but because of its intense poignancy – the “human element” deployed ceaselessly by mass media to certify the truthfulness of its products?

Another example of Hendeles’s use of photographs is the groups of images presented in Predators & Prey, one of two exhibitions now on view at the Ydessa Hendeles Art Foundation. In this show, Hendeles has largely (though not completely) abandoned exhibiting deluxe artworks of museum quality and elaborated the tactical arrangement of vernacular photographs that we saw in the Teddy Bear Project.

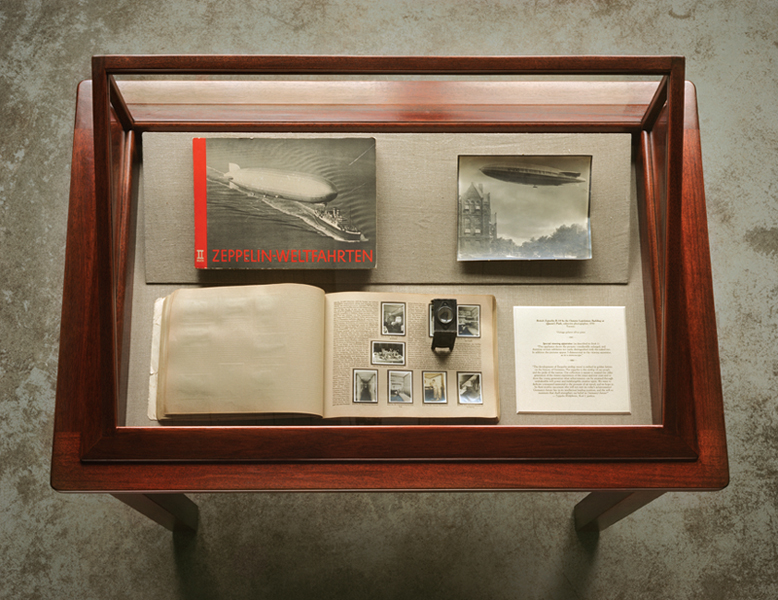

A pair of gleaming, sexy, gold high-heeled shoes (symbols of both the sexual predator and the prey), a vampire-killing kit (complete with a pistol and silver bullets), a set of porcelain dishes from the ill-fated Nazi airship Hindenburg – such items are in themselves souvenirs and curiosities with minor intrinsic interest. In the context provided by the exhibition’s title, however, they become elements in a complex allegory of everyday life that operates at many levels: the chase of psychoanalysis after deeply buried secrets, the unceasing hunt for sex, the more deadly hunt for the vampires and phantoms that haunt modern imagination.

The adjacent groups of airship photographs in Predators & Prey – German cigarette-pack souvenir landscape photographs snapped from the gondolas of dirigibles in the 1930s, and Associated Press pictures of the fiery death of the airship Hindenburg in 1937 – blossom with new and darkly radiant meaning. The seemingly innocent shadow of an airship passing over world capitals prophesies the sinister political shadow of Germany’s ambitions that will fall over the whole planet only a few years later. The news photos, similarly, are now reminders of the craving for spectacle – the ultimate journalistic prey – that drives news organizations and testify to the power of mass media to deliver sensational imagery to consumers made hungry for sensation by the endless shocks of modernity. In this scenario, we are both predators and prey, locked in the informational cycles of industrialized society.

Such a society is the only cultural reality that most people on Earth have ever known. Ydessa Hendeles’s collections of photographs take us deep into the pathologies and contradictions of this culture, and into the contemporary anxieties that underlie its bright flux of mass-mediated imagery.

John Bentley Mays has been the visual arts and architecture critic for The Globe and Mail and a columnist for the National Post. He is the author of In the Jaws of the Black Dogs: A Memoir of Depression; Emerald City: Toronto Visited; and Power in the Blood: Land, Memory and a Southern Family, which was short-listed for the first Viacom Canada Writers’ Trust Non-Fiction Award and named a 1997 Notable Book by The Globe and Mail. He is also the winner of a National Newspaper Award and four National Magazine Awards.

Recipient of a Governor General’s Award for curatorial innovations and philanthropic accomplishments, Ydessa Hendeles has amassed one of the most highly regarded private contemporary art collections in the world. She is a member of the International Council of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA, New York), the Tate International Council (London), The Photography Acquisitions Committee of the Jewish Museum (New York), the Dia Council (New York), and the International Council of the Museum of Contemporary Art (Los Angeles).