by Pierre Dessureault

Robert Walker turned to photography in 1975, after detours into abstract painting and conceptual art. Imagery was present in his conceptual production in the form of quasi-generic, literal photographs that he used as evidence of his interventions in the public sphere, either as cultural signs bearing ideas, or as found objects that were integrated into collages. This work with and by the image was situated within a search for art engaged with life and social issues. In this radical perspective, photography served as a tool to cast the bourgeois aesthetic object into question, while at the same time the medium itself questioned the veracity of what it portrayed and sought to find a place in an emerging media world.

After he took a workshop with Lee Friedlander, Walker began to examine the social landscape. The American critic and educator Nathan Lyons had formulated his concept of this approach in an exhibition that he organized in 1966, Towards a Social Landscape, featuring photographs of Bruce Davidson, Friedlander, Gary Winogrand, Danny Lyon, and Duane Michaels. The unifying feature of these artists’ practices, at first glance individual and disparate, was exploration of the North American city, and the proliferation of signs invading the streets, in snapshots. This procedure recalls the figure of the detective, the modern form of the flâneur in Baudelaire’s Paris described by Walter Benjamin: “He [the detective] worked out forms of reactions that fit the pace and timing of the big city. He caught things on the fly; he could thus dream of himself as an artist. Balzac felt that the essence of the artist, in a general sense, resided in the rapidity of capture.”1 This arm’s-length picture, with no preparation, reflection, or calculation, fixed motion in the precarious instability of the moment and conveyed the shock of the encounter between photographer and city. It was not the euphoric, utopian first glance upon things claimed by art, but the emergence of a fleeting vision saturated with the images that speed by in the urban chaos.

Walker made his nest in the crowds and bustle of the streets of New York, Montreal, Warsaw, Paris, Rome, and Toronto. “The crowd is his domain, like air is the bird’s domain, like water is the fish’s. His passion and his profession is to follow the crowd. For the perfect flâneur, for the passionate observer, there is immense enjoyment in taking up residence in numbers, in the flow, in movement, in the fleeting and infinite. Being away from home, and yet feeling at home everywhere; seeing the world, being at the centre of the world, and remaining hidden to the world – these are some of the pleasures of these independent, passionate, impartial spirits that can be defined by language only clumsily. The observer is a prince who enjoys going incognito everywhere.”2

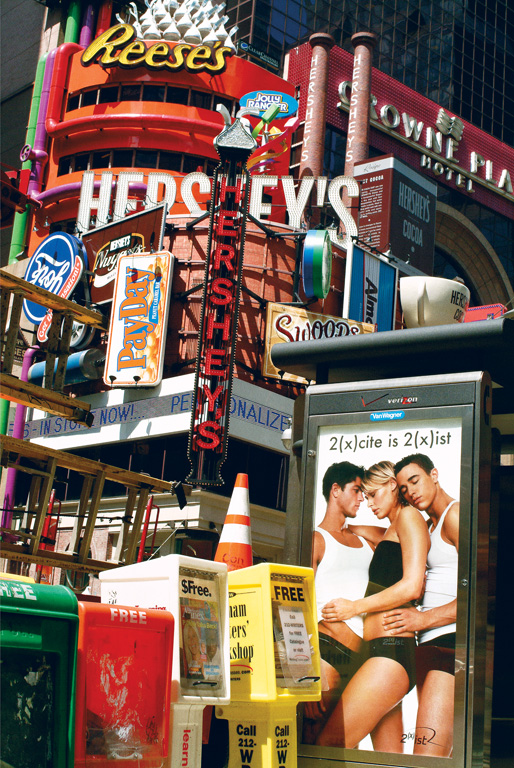

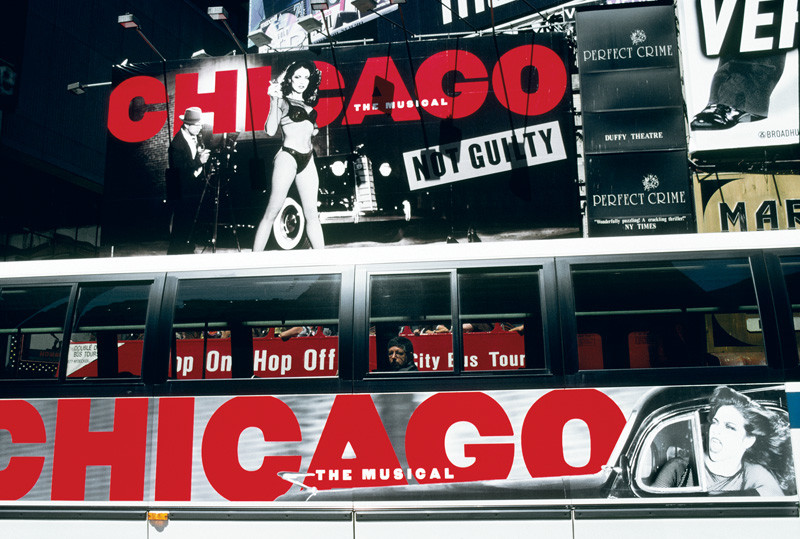

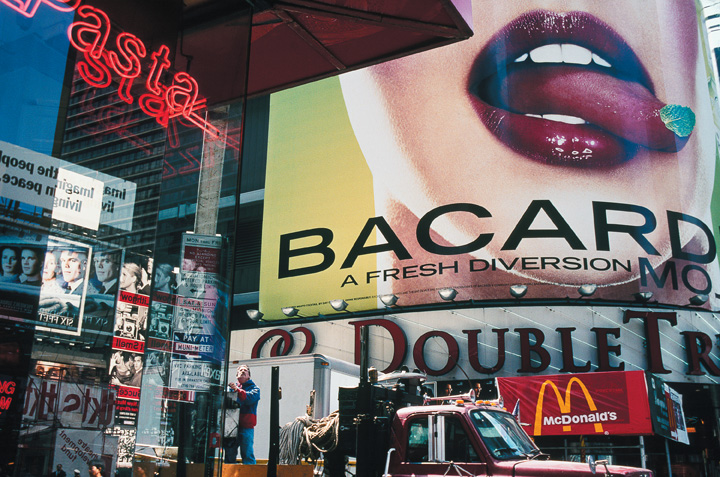

Walker’s images, true collages of impressions, are composed of collisions of discordant elements brought together by the most improbable chance juxtapositions. Shop windows in which superimpositions and reflections play, garish neon signs, truncated posters selling dreams, graffiti, anonymous passers-by acting as extras running from the gaze in all directions, and buildings seen from striking low angles coexist in utter disorder and fight for attention in a pictorial space cut up into jutting angles. The frame of the image cuts straight through, punching out a dense and compact piece of reality without holding back the unfurling of urban forms that flee and overflow on all sides, leading the eye toward an improbable “off-screen.” This way of playing off visual dissonances by creating clashes is in some ways the equivalent of the “cut-ups” of novelist William S. Burroughs, who, by random cutting and pasting of texts brought out, from already formed material, a new way of seeing and feeling. In his preface to Walker’s book of photographs of New York, Burroughs describes this flip side of the visible and ordinary perception that the photographer and the writer should reveal in their art: “The object of art is to make the reader or viewer aware of what he knows but doesn’t know that he knows…. And this is doubly true of photography, because the photographer is making the viewer aware of what he is actually seeing yet at the same time not seeing.”3

The saturated public space of contradictory messages becomes a composite pictorial space in which words, colours, and forms structure the image, a smooth surface stripped of narrative content, usually in a vertical frame to echo the city’s upward thrust. Signs, notices, and graffiti have carved out a starring role in the avalanche of overlapping, telescoping planes. Their words are more than graphic signs or gestural traces executed in the spontaneity of the moment; they relay clues to social values. For example, Color Is Power, appearing on a billboard in New York, was originally an advertising message for Avon that, once diverted, became a statement of principle for Walker and the title of one of his photography books. 4 Extirpated from the marketing culture of which it is a product, just like the merchandise that it must sell, the advertising slogan acquires a universal scope. Its evocative power, magnified by diversion and assemblage with other elements in the urban setting, restores to words their strength of expression and meaning.

Whichever city he finds himself in, Walker shows us the same thing: the invasion of the urban space by advertising and ever more eye-catching images, and the resulting flattening of particularities.

Walker works in daylight and prefers the raw light of noon, which intensifies contrasts and saturates colours. He uses colours not for their descriptive properties or as an accent designed to create an ambience or add a touch of symbolism to the scene, but as a visual element, bearing expressive qualities. As he did in his early career as a painter, Walker draws on the chromatic vibrations produced by the proximity of great stretches of colour with clearly cut contours. “If my work has an affinity with painting, it is probably because I compose the pictures with an abstract sensibility. When I choose my subject to be photographed, while composing I forget about the literal elements and think only of balancing the colour and form. I think if I learned anything from my early days of painting, it was to be able to look at the entire picture plane as an abstraction and not to be seduced by dramatic subject matter.”5

Whichever city he finds himself in, Walker shows us the same thing: the invasion of the urban space by advertising and ever more eye-catching images, and the resulting flattening of particularities. Standardization is the rule. Like the rooms of large hotel chains that are the same everywhere so that the traveller is not disoriented, the streets of all Western large cities offer the stroller the same setting, the same horizonless landscape. The same laws apply everywhere: those of mercantilism. The street has become advertising space. The flâneur wanders “in the labyrinth of merchandise as he once wandered in the labyrinth of the city.”6

Translated by Käthe Roth

1 Walter Benjamin, Charles Baudelaire. Un poète lyrique à l’apogée du capitalisme (Paris: Payot, 1979), p. 63.2 Charles Baudelaire, “Le peintre de la vie moderne,” in Charles Baudelaire critique d’art, vol. 2 (Paris: Librairie Armand Colin, 1965), p. 449.

3 William S. Burroughs, “Introduction to the book of photographs by Robert Walker”, New York Inside Out (Toronto: Skyline Press, 1984), n.p.

4 Robert Walker, Color Is Power (New York: Thames & Hudson, 2002).

5 “Magdalena Ignaczak talks to Robert Walker, Lodz-Montreal, March 19th, 2001,” in Robert Walker: Color is Power (Lodz: Museum Sztuki, 2001), p. 24.

6 Benjamin, Charles Baudelaire, p. 82.

Pierre Dessureault was curator at the Canadian Museum of Contemporary Photography. He has organized numerous exhibitions and published numerous catalogues about contemporary photography. He is now a photography historian and an independent curator.

Robert Walker was born in Montreal, where he studied painting at Concordia University. In the mid-1970s he developed a keen interest in street photography and moved to New York. His first book, New York Inside Out, was published in 1984. He has exhibited widely in the United States, Canada, and Europe. His latest book, Color Is Power, was published by Thames & Hudson in 2002. He now divides his time between Montreal, New York, and Warsaw.