www.atsa.qc.ca

by Bernard Vallée and Pierre Anctil

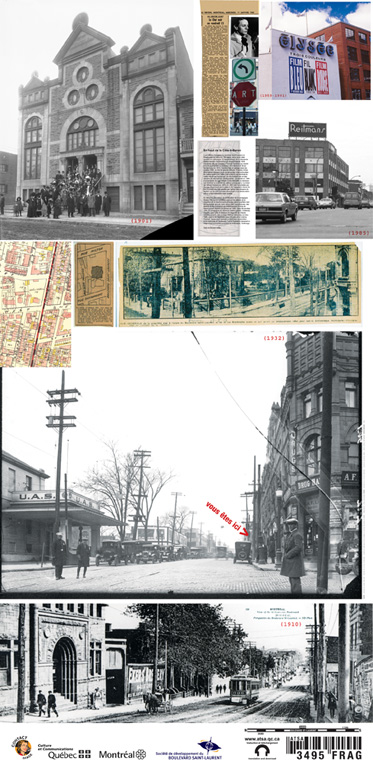

You are at 3495 Saint-Laurent

On top of Baron Hill

It is difficult to imagine the intersection of Saint-Laurent and Sherbrooke streets in the early nineteenth century, when the area was still rural. Where today a rather sad service station sits once stood an opulent villa built by arms merchant Thomas Torrance in 1818; it then became the property of brewer John Molson and his family, who owned it until 1910. Converted into a garage in the 1930s, the villa was later destroyed. From this vantage point on Côte-à-Baron (Baron Hill), which overlooked the old city and its outskirts, many rich Montrealers flaunted their sumptuous begardened villas: the Notman villa is one of the last remaining of these remarkable buildings. Commissioned in 1844 by Judge William Collis Meredith, the residence became the property of well-known Montreal photographer William Notman in 1876. In 1891, it was bought by George Drummond to house St. Margaret’s Home for the Incurable. More recently, it was saved by the efforts of neighbourhood residents opposed to its devaluation by a mediocre real estate development project.

In the early twentieth century, the construction of the Sharre Tfile synagogue on Milton Street marked the beginning of the Jewish community’s migration from the old neighbourhoods toward the northern outskirts, and of the factories, workshops, and storefronts that were springing up along St. Lawrence, officially a boulevard since 1905. In the 1950s, the synagogue became a Yiddish theatre, the Melody Theatre; then a night spot, the Chat noir, owned by singer-songwriter Claude Léveillé; and finally, from the 1960s to the early 1990s, a repertory cinema housing the Élysée and the Cinéma Festival. After being home to Business, the boulevard’s first trendy bar, the Reitman’s factory building became the headquarters of multimedia pioneer Softimage.

Original text by Bernard Vallée

Translation by Nazzareno Bulette

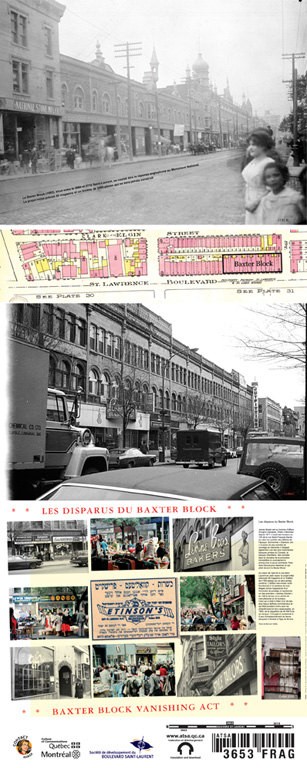

You are at 3653 Saint-Laurent

The lost diamond of the Baxter Block

James Baxter was a businessman of Irish descent. In 1877, he moved to Montreal and set up his offices at 120 Saint-François-Xavier, in the heart of that era’s business district. Nicknamed Diamond Jim because of his diamond brokerage interests, he also managed one of Canada’s largest privately held banks, the Ville-Marie. His interests in real estate development led him to hire the young architect Théodore Daoust to design what would be the Baxter Block. Centrally located along a burgeoning St. Lawrence Street, the initial project called for 28 stores, as well as a 2,500-seat theatre (never built). The multi-use neo-Roman building, with its 14 three-storey sections, had a prestigious façade and is considered one of the first “shopping centres”; it was also a manufacturing centre and office building. The man who gave the Main one of its most beautiful commercial buildings and was known for his philanthropy was nonetheless found guilty of the 1900 embezzlement of $40,000 from his bank. He was sentenced to five years’ imprisonment and died soon after his release, at age 66.

Original text by Bernard Vallée

Translation by Nazzareno Bulette

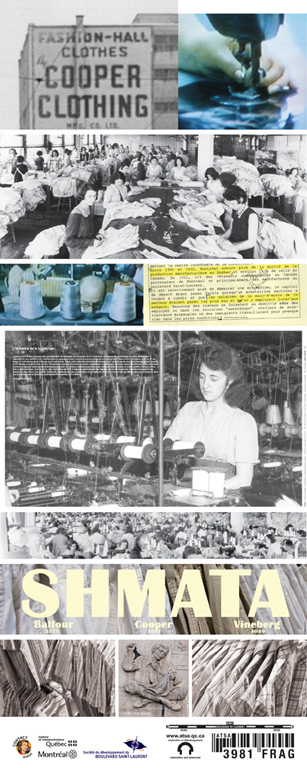

You are at 3981 Saint-Laurent

The garment industry

For almost 60 years, St. Lawrence Boulevard was the centre of Canada’s garment industry, as evidenced by several of the city’s landmark buildings, including the Balfour at the corner of Prince-Arthur, the Cooper near Bagg St., and the Vineberg at the corner of Duluth. In this once thriving industry, a great many owners and workers were of Jewish descent, although there were workers of all nationalities, including, in the 1930s, a large number of French-Canadian women. The industry gave rise to labour movements and large-scale social conflicts, such as the women garment workers’ strike in 1937, in which prominent figures from the political left, such as Léa Roback, participated. Today, these large buildings, long abandoned by seamstresses and tailors, have become home to the artists and multimedia firms currently thriving on the Main.

Original text by Pierre Anctil

Translation by Nazzareno Bulette

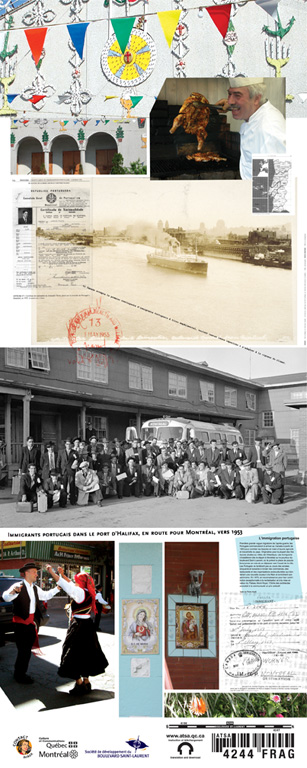

You are at 4244 Saint-Laurent

Portuguese immigration

Constituting the first great wave of immigration of the post-war period, the Portuguese began arriving in Canada in 1953 to fill the country’s need for agricultural and industrial labour. These immigrants, most of them from the Azores archipelago in the middle of the Atlantic, quickly settled on streets adjacent to St. Lawrence Boulevard, where they replaced the Jewish populations that were moving westward in the city. It did not take long for the Portuguese to open stores, restaurants, and sociocultural organizations in the 1950s and 1960s. These gave the Main new colour and enriched its heritage. In 1975, in recognition of its exceptional contribution to the revitalization and enhancement of Plateau Mont-Royal, the Ordre des architectes gave the Portuguese community an award.

Original text by Pierre Anctil

Translation by Nazzareno Bulette

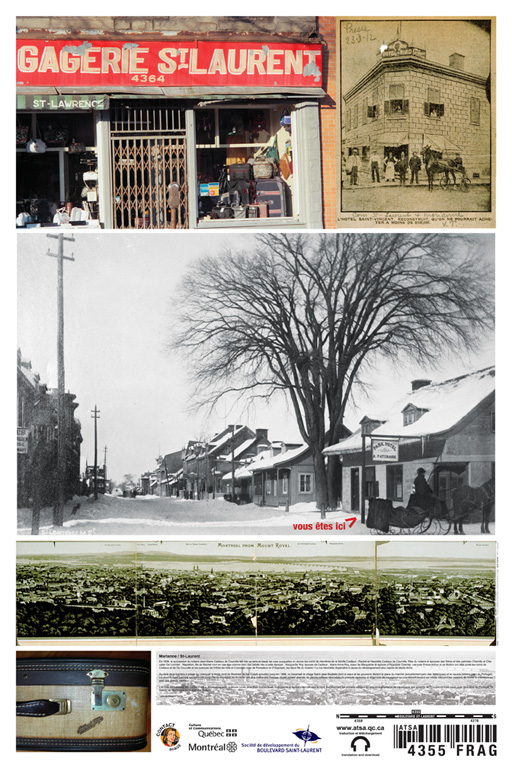

You are at 4355 Saint-Laurent

Marianne/Saint-Laurent

In 1834, the heirs of notary Jean-Marie Cadieux de Courville subdivided his land and laid out the streets which were to bear the names of members of the Cadieux family: Rachel and Henriette Cadieux de Courville, daughters of the notary and wives of the very patriotic brothers Chamilly and Chevalier De Lorimier; Napoléon, Rachel’s son, who died as an infant, as did many babies born in that period; Marguerite Roy, wife of Cadieux; and Marie-Anne Roy, Marguerite’s sister and wife of Hippolyte Cherrier. Prince-Arthur and De Bullion streets were previously called, respectively, De Cadieux and De Courville, and Hôtel de Ville and Coloniale avenues once bore the respective names of Pantaléon and Hippolyte, the notary’s two sons! Henriette Street eventually disappeared due to the rapid expansion of Marie-Anne Street.

Beyond the toll booth that marked the north city limit of Montreal until 1886 (present-day Duluth Street) lay the village of Saint-Jean-Baptiste, whose heart was the market square (today’s Parc des Amériques) and Vallière Square (now Parc du Portugal). St. Lawrence Street, which crossed the entire island of Montreal from the old city to the Rivière des Prairies (sometimes called the Back River), saw the passage of wagon-fulls of cut stone, cartloads of produce, and stagecoach loads of travellers stopping at the hotels alongside the farmhouses and the tradesmen’s workshops at the foot of the large elms.

The arrival of the tramway disrupted this bucolic tranquillity, and the industrious and festive immigrant Main extended northward, transforming the old villages into neighbourhoods teeming with urbanity and the influences of Jewish Central Europe and later of Portugal, Greece, South America, and the West Indies.

Original text by Bernard Vallée

Translation by Nazzareno Bulette