[Summer 2009]

Canadian Museum of Contemporary Photography at the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

October 31, 2008 – March 22, 2009

What if sacred masks and the geopolitical pomp of costumes had preceded posed portraits and scenes for the camera? Then, in the photographic gaze, not only would there be different works, but there would also be a legitimate Aboriginal critique through art. And this is precisely what works in Steeling the Gaze: Portraits by Aboriginal Artists offer – they let us “see” the current identitary, personal, and community issues between Aboriginals and non-Aboriginals in Kanata (Canada) and Gépèg (Quebec). In this regard, this first institutional collaboration between the Canadian Museum of Contemporary Photography (CMCP) and the National Gallery of Canada (NGC) in Canada’s national capital (Ottawa/Gatineau), pairing a non-Aboriginal curator (Andrea Kunard) and an Aboriginal curator (Steve Loft) to create an exhibition of some fifty works by twelve Aboriginal and Métis artists, is praiseworthy.

Stealthily entering the first gallery, I was immediately struck by the intense visual symbolism of how the artworks occupied the space.

On the left-hand wall, the photographs by Jeff Thomas (Onondaga), excerpted from the series Four Indian Kings, Warriors Rule, and The Delegate, stretched out horizontally at eye level in the form of the great Huron-Iroquois Hiawatha Wampum. Some images mixed European paintings of chiefs with contemporary Iroquois figures (e.g., the Mohawk artist Joe David, a “warrior” at Kahnesatake in 1990). Others paired historical photographs of clans with the urban traces of today’s monuments – in many of which Thomas’s son, Bear, appeared. In these works, Thomas explored his personal integration through the changes of territoriality experienced between the “invented Indian” of the past and the “Aboriginal” of today. He states, “You won’t find a definition for ‘urban Iroquois’ in any dictionary or anthropological publication – it is this absence that informs my work as a photo-based artist, researcher, independent curator, cultural analyst, and public speaker. My study of Indian-ness seeks to create an image bank of my urban-Iroquois experience, as well as [to] re-contextualize historical images of First Nations people for a contemporary audience. Ultimately, I want to dismantle long entrenched stereotypes and inappropriate caricatures of First Nations people.”

I turned my head. Breathtaking! On the right-hand wall, five fascinating larger-than-life images “explode” facial expressions distorted by gestures of the fingers and hands. These exceptional photographic portraits, created by Arthur Renwick (Haisla of the Northwest Coast), look out at us. In turn, Michael, Tom, Eden, Jani, and Monique – from the series titled Masks – powerfully embody the genesis of “mask/faces,” forms of representation, portraits that belong only to the time immemorial when mythological “passages” between the world of Humans and the world of Animals and Okis (spirits) were common. As I stared at them, I thought I heard the heartbeat of this exhibition. The artist did not have to express himself in words on the wall.

Were Renwick’s Masks in a visual “dialogue” with Thomas’s Wampum, as if to better frame the images on the large centre wall, I wondered. These were six imposing portraits from the series Mustang Suite by Dana Claxton, who describes herself as “Lakota Sioux Canadian.” Certainly, the hyper-modern, humorous look of the large colour photographs flirted with the canon of advertising images. Members of an Aboriginal family (e.g., Family Portrait [Indians on a Blanket]) posed in various scenes caricaturing North American hyper-consumption, where they exhibited seemingly traditional Aboriginal artefacts. These works could not fail to catch the eye . . . of the media!

This “triptych” in the first room seemed persuasive to me, as did the curators’ bold idea of placing on the walls the artists’ personal reflections about their identitary quests. Even if they were but mediations, some of the texts shone light on the artists’ creative attitudes for viewers strolling among the works in the second gallery.

Whether it was a few excerpts from the late Carl Beam’s The Columbus Project or the Teensy Nun Production videos by the young Métis artist Thirza Cuthand and BrockDickDog by Bear Witness (Cayuga), a number of variants on the theatricality of identitary plays, exposed specifically through photographic portrait sessions, awaited viewers. The “Cree/Scottish” photographer KC Adams set the tone with her alignment of constructed portraits produced during a creative residency at the Banff Centre, the Cyborg Hybrid series, for which she put her artist friends in “glamour Indian make-up.” The “imaginary museum” in three photomontages (Ann. E Visits Emily, The Artist in Her Studio, Searching for My Mother) by Rosalie Favell (“Métis, Cree/English,” as she describes herself) revisited, in a surrealist mode, icons such as Emily Carr and the Virgin Mary, with an embroidered Kateri Tekakiwita on her heart. The Emergence of a Legend, small self-portraits in disguises, embossed on metallic paper by Kent Monkman (of Cree heritage), were in the vein of set pieces. For Monkman, although pomp, costumes, and permissive socialization of the dominant world (the West) allow flights of individual freedom, they also reveal confused acculturation: “A lot of my work also deals with colonized sexuality due to the influence of the church on our community – as forcibly as putting people into residential schools – and the influence of Judeo-Christian values. We’ve been colonized on many levels and one of the things that has been affected has been our sexuality.”

Of course, the heritage of civilization was not absent. While the black-and-white “classic” photographs of a David Neel (Kwakwaka’wackw’) pay tribute to traditions and its great portagers and promoters (e.g., Sitting Bull, Bill Reid, Elijah Harper), Gregg Staats (Kanien’kéhaka) with his photomontages combining territory and members of his community (Breathe, Accept Loss) brings out the underside of the place: the current precariousness flowing from wounds, “reductions,” and censorship of Aboriginal languages, today almost all in peril. Staats reintroduces the need for a healing process.

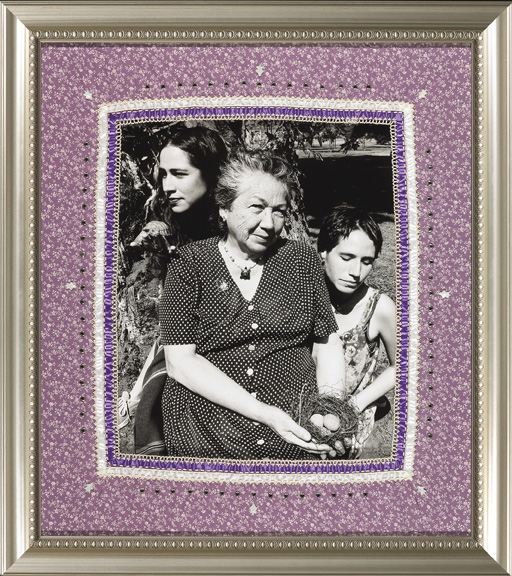

One photograph caught my eye for its truth of the “steely gaze”: Time Travels Through Us, the famous framing of golden wood and finely woven beadwork with a beautiful black-and-white photograph of three Iroquois women at its centre – three generations of faces that, by their light, and the composition of bodies pressed against each other, breathed not just survival but confidence. From this subtle work by Shelly Niro, I felt the universal message: that of hope-individuals and hope-communities.

As I left the exhibition I glimpsed in the Gallery’s imposing windowed entrance hall Ayum-ee-aawach oomama-mowan: Speaking to Their Mother, the famous megaphone designed by Rebecca Belmore to speak aloud to Mother Earth. I reflected. Although very interesting, this exhibition needed some nuances, especially in these times, when it is perhaps too easy for anyone to be anyone else, the term “Aboriginals” is used as a syncretism homogenizing all First Nations to name, without distinction, Indigenous people, Amerindians, Métis, Inuit. It must be kept in mind that there are 611 First Nations spread from east to west on reservations in Kanata, including 10 in 54 communities in Gépèg.

To these are added the Métis Nation of the Prairies and the Inuit of Nunavut and Nunavik, as well as non-Status mixed-blood individuals – whence the richness and complexity of inter-nation identities.

In fact, the works in Steeling the Gaze were mainly by Iroquois, Prairies Métis, and Northwest Shore Indian artists, with none from east of the Great Lakes – thus none from Gépèg. There is, however, an Aboriginal photographic art presence in the east. One has only to think of Rebecca Belmore’s magnificent self-portrait Fringe, on view throughout 2007 on a billboard at the corner of Duke and Ottawa streets in Montreal above the premises rented by the Grand Council of the Crees. What can be said about works by Jeff Thomas and Gregg Staats, two of the artists in Steeling the Gaze, who were also represented in the exhibition of large photographic banners Zacharie “Tehariolin” Vincent et ses amis at Espace 400e (Québec 1608–2008)? There would also be much to see of the “photographic spirit” behind the work of Sonia Robertson in Mashteuiatsh among PiekuakaIlnuatsh (Innu), but it is also the revealing “photographic mission” titled Photographe sans condition by Kathleen Penosway, Tracy Stella Brazeau, and Mani Sigon Papatie exposing the difficult living and housing conditions in Kitcisakik, the Algonquin reservation in distress in Abitibi-Témiscamingue that I remember. It was presented at the new Hôtel-Musée in Wendake in May 2008.

Thus, the “steel gazes” projected into the future will soon have to be broadened from West to East.

Translated by Käthe Roth

Huron-Wendat, Guy Sioui Durand has a doctorate in critical sociology and is an independent curator specializing in contemporary and Aboriginal art. Co-founder of the magazine Inter and of the artist-run centre Lieu (Quebec City), he has published three books, including L’art comme alternative (1997). He writes for periodicals and catalogues and on the Internet. He was the Aboriginal consultant for Espace 400e (Québec 1608–2008). www.siouidurand.org